Elements of the text are used in articles for Current Archaeology (CA 414) and CBA’s Archaeology in Wales (2024)

Mike Woods

Heneb Gwynedd

Arwyn Owen

PhD student, Manchester Metropolitan University

George Nash

Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool

To discover a new Neolithic chambered tomb is considered a rare occurrence; however, to find a chambered tomb, two standing stones, a later prehistoric or early medieval enclosure and, pertinent to this article, three later prehistoric rock art panels is extraordinary!

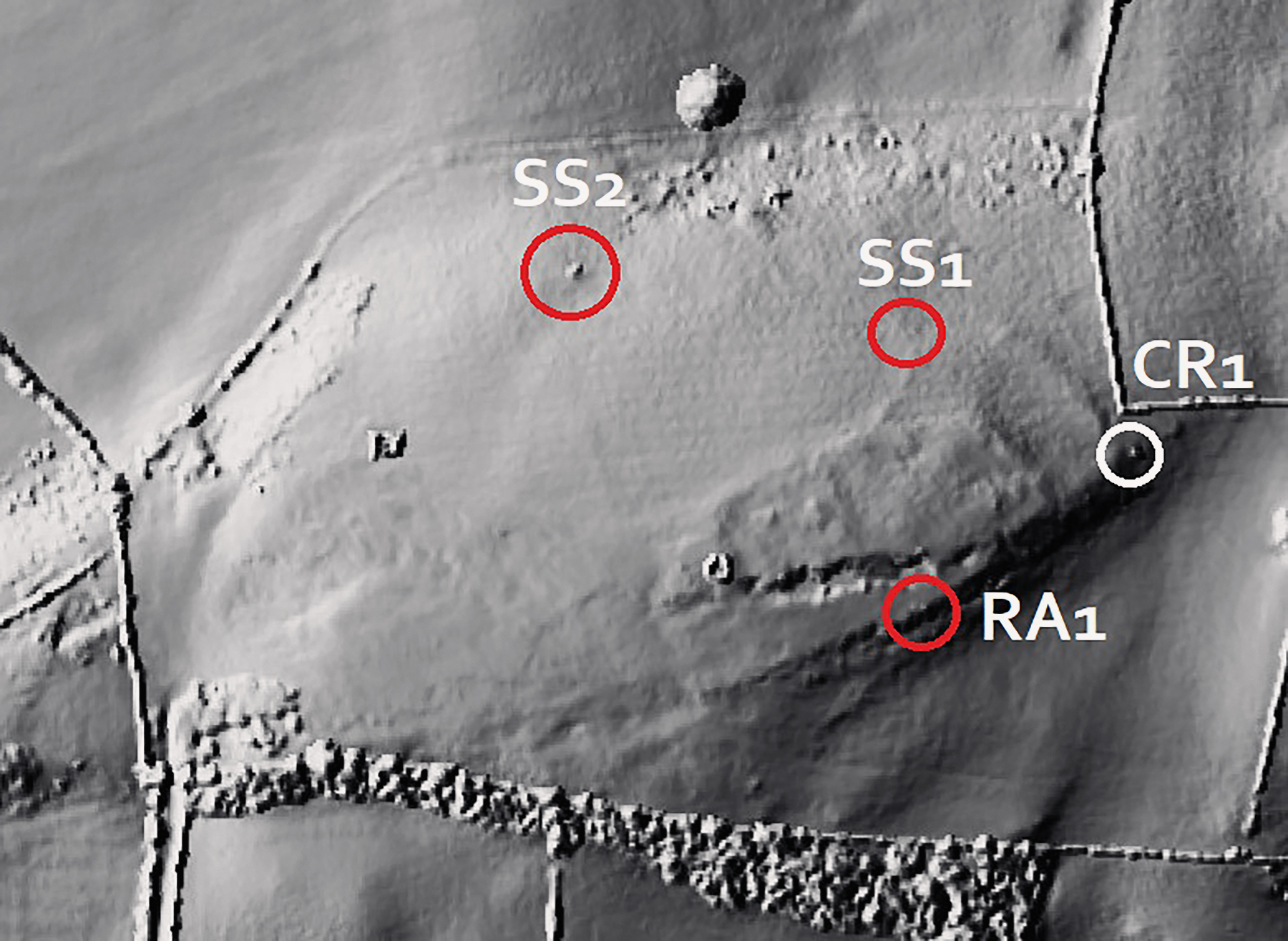

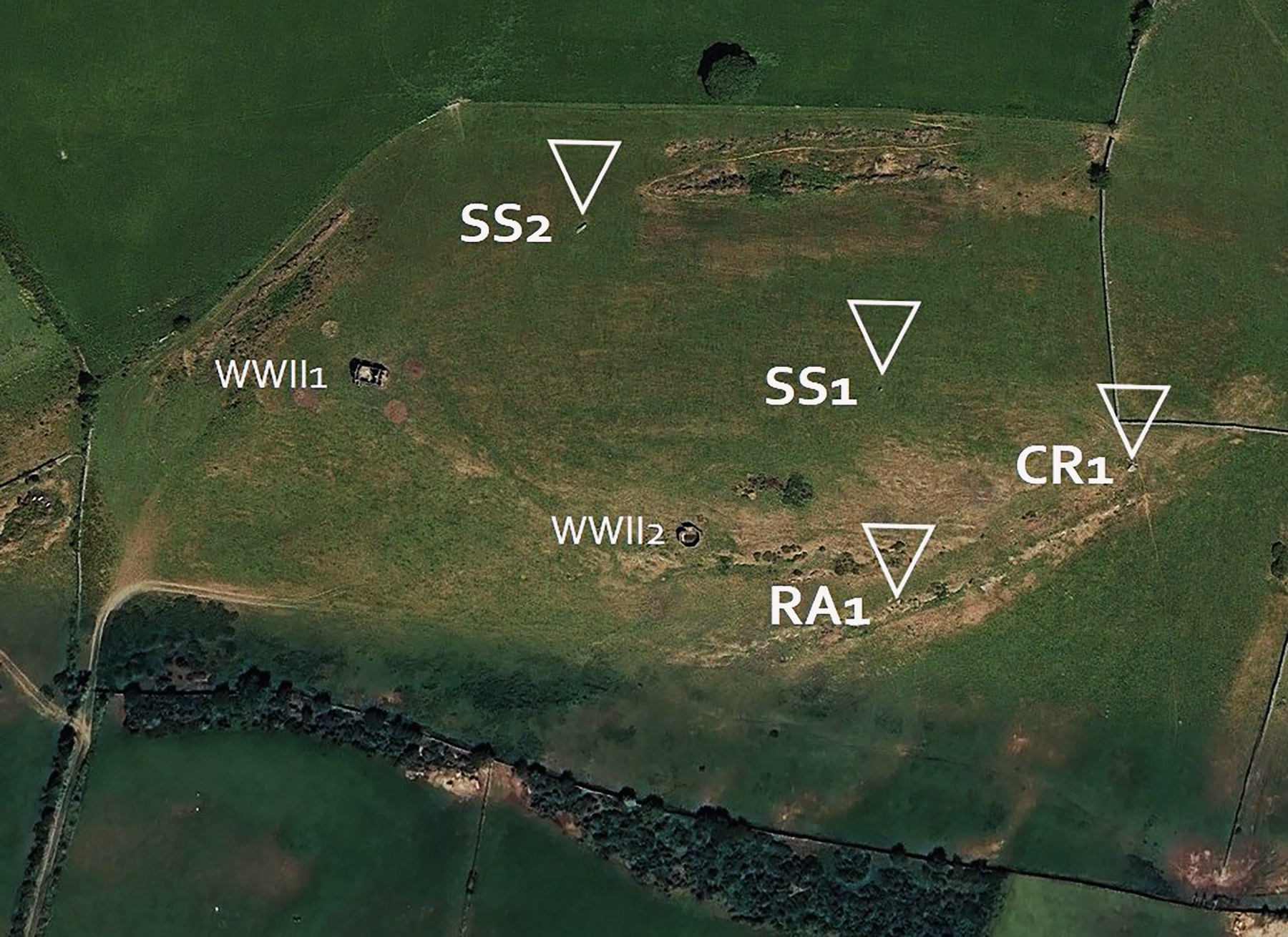

In 2020 Mike Woods and Arwyn Owen discovered this site complex on and around the summit of a small but prominent hillock known as Pen y Foel. The then possible chamber tomb was partially excavated, and the results subsequently published. In 2023 and 2024, George Nash was invited to verify and record the three rock art panels. The team were largely in agreement that this complex had potential significance, revealing through LiDAR, the remnants of a group of later prehistoric monuments that formed a fragmentary ritualised landscape. This article takes the reader on a journey of discovery of a Neolithic/Bronze Age symbolic landscape that is only one of three that are present in Ynys Môn.

In 2021, the authors with a team of volunteers excavated a potential megalithic site known as Bedd y Foel which is located on the lower western slope of Pen y Foel, a small but strategic hillock (the hillock is locally known as the Foel, meaning the bald or barren) (Plate 1 & Plate 2). In addition to the fieldwork, the team also surveyed the wider landscape, using a variety of desk-based techniques including satellite imagery and LiDAR. These approaches assisted in allowing the team to identify other potential sites that occupied the summit and lower slopes of Pen y Foel.

Ynys Môn has a long history that now extends back to the latter part of the Late Upper Palaeolithic (based on several dated pits located south of Wylfa). The most visible monuments though are the stone chambered burial-ritual sites and their associated landscape monoliths of the Neolithic and Bronze Age periods. These sites, have over the past 150 years been the focus for antiquarian and archaeological investigations (see Baynes 1910-11; Lynch 1976). The Neolithic passage graves of Barclodiad y Gawres and Bryn Celli Ddu, excavated during the early to mid-20th century using then up-to-date fieldwork techniques provided many answers to understanding the burial practices for this monument type (Hemp 1930; Powell & Daniel 1956). However, other sites, classified as Dolmens (and sometimes referred to as Cromlechs) have an unfortunate archaeological past, due mainly to antiquarian investigations, with much of the contents from each monument being archaeologically unrecorded, stratigraphy unceremoniously removed and artefacts ending up in private collections – their context lost.

Based on extensive surveys around Wales, it appears that many, if not all Neolithic and Early Bronze Age burial-ritual sites would have been associated with landscape monuments, such as standing stones and stone rows (e.g., Britnell & Whittle 2022; Cummings & Whittle 2004; Tilley 1994). The regional Historic Environment Record (HER) contains a list of at least 65 standing stones in Ynys Môn. These enigmatic structures usually occupy the same landscapes as the burial-ritual stone chambered monuments. It is more than probable that many more standing stones and burial-ritual monuments existed but have been destroyed, removed, reinstated elsewhere or await discovery. Indeed, the antiquarian, the Reverand John Skinner undertook a 10-day tour of Anglesey in 1802 and remarked in his diary that he had witnessed the dismantling of at least six monuments during his stay (Skinner 1802 [transcribed by T.P. Williams 2004]). Based on Skinner’s account and other antiquarian records, monuments had begun to lose their [supernatural] power, and the folklore associated with this group of monuments, and as a result, they became collateral victims. This 18th and 19th century mindset marks the final death knell in protecting such sites. In many instances stone chambered monuments became nothing more than quarries for the construction of buildings, field boundaries and road construction (e.g., Brück 2001). Today, many of the Neolithic burial-ritual monuments in Ynys Môn (and elsewhere in the western British Isles) are incomplete, a victim of the dismantling that took place during this time; the site of Bedd y Foel and its associated landscape monuments is no exception to this Age of Enlightenment!

The natural geology of the locality comprises a gritstone; however, the monuments identified within our landscape survey, including the capstone, the two standing stones and the rock art panel on the southern ridge of the hill indicates the geology to be of hornblende picrite (BGS). This specific geology is an igneous rock that is only found in a few isolated surface outcrops; one of these being around nearby Llanerchymedd. Despite the availability of the gritstone geology around the summit of Pen y Foel, it appears that monument builders were selective in the material they used in construction. It is conceived that colour and lustre of the minerality of the hornblende picrite may have attracted attention for monument construction.

The newly discovered site of Bedd y Foel is located on the western slope of Pen y Foel. Despite its height and relatively small surface area, this natural feature has commanding views across much of northern Ynys Môn and is intervisible with the Bronze Age copper mine on Parys Mountain, and possibly, two Neolithic burial-ritual monuments within the coastal village of Benllech – Pant y Saer and Glyn. During the Neolithic period, the immediate landscape would have probably accommodated more standing stones, probably acting as processional markers, whereby communities with their dead would descend onto burial monuments in a proscribed way, across a landscape from their settlement areas [similar to the corpse roads of the medieval and early post-medieval periods] (Children and Nash 2001). Today, and based on Ordnance Survey mapping and the HER, the area around Pen y Foel has at least six standing stones and it is more than likely that these monoliths would have had an association with one or more burial-ritual stone chambered monuments: one of these possibly being Bedd y Foel.

Prior to full scale excavation in May 2021, a strip, map and record programme were conducted in September 2020. This programme allowed the team to target several areas for excavation, including an area measuring 4m x 4m immediately west of the capstone (Plate 3). This work identified a layer of demolition rubble likely associated with monument activity. Several large stones were recorded, one with two faint cup marks and twin parallel grooves carved on its surface which may have been structural in nature – possibly the top of an orthostat (upright). In addition, a fragment of hornblende picrite was recovered – closer examination suggests that it may have been later modified to enhance two igneous inclusions which run parallel across the piece, evident with the presence of possible lateral tool marks along its edges (Kenney, pers. comm.).

As stated earlier, many monuments in Ynys Môn survive in varying states of poor preservation (e.g., Cromlech Farm [NGR SH 3604 9201], Din Dryfol [NGR SH 3963 7254], Hen-Drefor [NGR SH 5512 7731] and Ty Mawr [NGR SH 5390 7224]). Although several of these sites have been previously excavated, the artifacts and the architectural state of each monument is difficult to discern (e.g., Smith & Lynch 1987). We would suggest that the current state of Bedd y Foel, plus the confused evidence associated with its recent past has similar issues with monuments mentioned above. This site was initially identified as a possible Neolithic burial-ritual monument in 2020. As a result of this assessment, the site was later excavated by Arwyn Owen and Mike Woods in 2020, with the excavation extending through the Covid 19 period in 2021.

The team, along with volunteers, excavated a 4m x 4m trench within the western section of the site; an area that had been previously investigated in September 2020. The rationale was to attempt to uncover the remains of a chamber. Although the condition of the tomb was fragmentary and heavily disturbed, the team was hopeful that undisturbed archaeology remained in situ within a secure stratigraphic layer under the rubble identified previously.

Features recorded during the full-scale excavation included a large, worked stone, measuring 0.37m in height, 0.60m in length and a width of 0.46m, which was found to have been placed within a small curvilinear cut pit, into the earthen deposit above the outcrop, along with a small assemblage of stones that maybe the remnants of a packing deposit. This deliberate stone arrangement probably represented the base of an upright that would have once supported the nearby capstone (see similar scenario in Smith 2013). Uncovered within the base of the trench was a distinct compacted clay and stone floor surface (see Plate 4). The shape of the surface was roughly triangular in plan and measured 1.30m NE-SW and 2m NW-SE. It is probable that this surface and the stratigraphy above it had been heavily truncated by later historic disturbance.

Other artefacts included a granite polishing stone that was found immediately south of the sharpening stone within the confines of the chamber. One end of the stone was worn flat. Comparable examples are reported at Neolithic tombs on Anglesey, such as nearby Pant y Saer (NGR SH 50962 82497) (Scott 1933), along with two worked pieces of black chert, which was found within the upper fills, above the clay surface. Although the finds from our excavation are considered meagre, we do stress that the monument proper had been relocated, albeit several metres to the east (as recalled by locals who remember the neighbouring dump being backfilled using plant machinery). It is more than probable that ground-truthing technology will, in the future provide some indication of the whereabouts of a cairn and other architectural features associated with this much-disturbed monument.

Apart from the Bedd y Foel monument, the team had also noticed three other sites worthy of further investigation, including two isolated monoliths, possibly prehistoric standing stones, and a large earth-fast boulder with engraved cupmarks on its upper surface (Plate 10, Plate 11 and Plate 12). The presence of these potential monuments reinforced the notion that sites on Pen y Foel constituted a ritualised later prehistoric landscape, whereby all the monuments recorded by our team interacted with each other, mainly via intervisibility and recognised architecture (e.g., Tilley 1994; Tilley and Bennett 2001).

Plate 11. (center) A large monolithic stone, possibly a menhir, located on the NW slopes of Pen y Foel

Plate 12. (right) Cupmarked stone, located along the southern ridge of Pen y Foel, overlooking central Ynys Môn and the Snowdonia Range beyond

Similar to the potential dolmen site and the other recumbent standing stone to the west, this monolith has commanding views across much of northern Anglesey, with the southern slopes of Parys Mountain in full view. Despite its smooth, rounded taper, the stone appears to have been damaged in the distant past and would have been taller than present.

The two standing stones and the dolmen form an intriguing alignment that is roughly orientated NW-SE, with the dolmen being the SE terminus point. It is probable that other landscape monuments occupied the land either side of the dolmen but have since been destroyed or incorporated into later field boundaries which are now hidden from view. We note that a standing stone is located east of Llwydiarth Esgob Farm, at NGR SH 44670 84315. This monolith appears to be a continuation of the Pen y Foel alignment. Other standing stones within the vicinity of the Pen y Foel ritual monument complex include stones at NGR SH 45215 83115 and NGR SH 46085 83370. All three monoliths appear to bridge the landscape gap between Pen y Foel and the Benllech group of monuments, located c. 9km to the east. Based on their distribution across the northeastern side of Ynys Môn, we could be witnessing a procession routeway between two burial-ritual monument clusters, whereby grieving communities and the dead are guided across the landscape via a line of standing stones.

Given the concentration of monuments within such a small area, Pen y Foel is probably only one of three later prehistoric areas in Ynys Môn that can be labelled as a later prehistoric burial-ritual complex; the others being the landscapes of Bryn Celli Ddu and Llanfechell Cromlech. All other extant Neolithic monuments on the island do not possess this concentration of diverse monumentality. The landscape that surrounds this monument cluster appears to be the result of strategic choice, whereby the compass views from the summit of Pen y Foel included much of the northern landscape of Ynys Môn, including the uplands to the north and west. Incorporated into this panoramic view is Mynydd Bodafon within the central part of the island and the Snowdonia Range further south. This strategic location would have provided the community using this monument complex with power, prestige and status (see Ray & Thomas 2018). Similarly, the cup marked menhir, located on the northwestern slopes of Pen y Foel has itself commanding views across much of northern Anglesey, including the Bronze Age copper mine of Parys Mountain, located 7km to the north. Unfortunately, the distribution of monuments we see today is probably only a fragment of a ritualised landscape that was in use, some 4,500 to 6,000 years ago.

BAYNES, E.N., 1909. The Excavation of Lligwy Cromlech in the County of Anglesey, Archaeologia Cambrensis. (7th Series), 9, 217-31.

BAYNES, E.N., 1910-11. The Megalithic remains of Anglesey, Trans. Hon. Soc. Cymmrod, 3-91.

BRITNELL, W. & WHITTLE, A., (eds.) 2022. The First Stones: Penywyrlod, Gwernvale and the Black Mountains Neolithic Long Cairns of South-East Wales. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

BRÜCK, J., 2001. Monuments, Power and Personhood in the British Neolithic. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. Vol. 7 (4), pp. 649-67.

CHILDREN, G. & NASH, G.H., 2001. Monuments in the Landscape: The Prehistory of Breconshire, Vol. IX. Hereford: Logaston Press.

CUMMINGS, V., 2009. A View from the West: The Neolithic of the Irish Sea Zone. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

CUMMINGS, V. & WHITTLE, A., 2004. Places of Special Virtue: Megaliths in the Neolithic Landscapes of Wales. Oxbow Books.

DANIEL, G.E., 1950. The Prehistoric Chambered Tombs of England and Wales, Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

HEMP, W.J., 1930. The Chambered Cairn of Bryn Celli Ddu, Archaeologia, 1xxx (1930) 179-214.

LYNCH, F.M., 1976. Towards a chronology of megalithic tombs in Wales. In G.C. Boon & J.M. Lewis (eds.), Welsh Antiquity (Essays mainly on Prehistoric Topics. Presented to H. N. Savory upon his retirement as Keeper of Archaeology. Cardiff: National Museum of Wales. 63-79.

LYNCH, F.M., 1991. Prehistoric Anglesey: the archaeology of the island to the Roman conquest. Llangefni: Anglesey Antiquarian Society.

NASH, G.H., 2006. The Architecture of Death: Neolithic Chambered Tombs in Wales. Hereford: Logaston Press.

NASH, G.H., BROOK, C., GEORGE, A., HUDSON, D., MCQUEEN, E., PARKER, C., STANFORD, A., SMITH, A., SWAN, J. and WAITE, L., 2005. Notes on Newly Discovered Rock Art on and round Neolithic Burial Chambers in Wales, Archaeology in Wales, 45, 11-16.

NASH, G.H., GEORGE, A., STANFORD, A. & WELLICOME, T., 2010. Recent excavation and recording program at the Llwydiarth Esgob Stone, Llandyfrydog, Anglesey, North Wales. Rock Art Research Vol. 27 (2), 257-60.

OWEN, A. 2020. ‘St Mary’s Church’ and ‘Smithfield’ / ‘Cae Llan’ Survey Area; Llannerch-y-medd; Desk Based Assesssment, 2020 (6th ed.). Unpublished Report.

OWEN, A. & WOODS, M., 2020. Y Foel, Llannerch-Y-Medd: An excavation report on a possible unrecorded megalithic tomb site in Central Anglesey, with evidence of prehistoric rock art. Unpublished Report.

PHILLIPS, C.W., 1936. An Examination of the Ty Newydd Chambered Tomb, Llanfaelog, Anglesey, Archaeologia Cambrensis. xci (1936), 93-99.

PHILP, R., 2021. Strip, Map, Excavate (SME): Cae Mawr, Llanerchymedd Anglesey, Pontypridd, Archaeology Wales (unpublished report).

POWELL, T.G.E., CORCORAN, J.X.W.P., LYNCH, F.M. & SCOTT, J.G., 1969. Megalithic Enquiries in the West of Britain, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

POWELL, T.G.E. & DANIEL, G.E., 1956. Barclodiad y Gawres, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

RAY, K. & THOMAS, J., 2018. Neolithic Britain: The Transformation of Social Worlds. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

RCAM (Wales), 1937. An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in the County of Anglesey. London. HMSO.

SCOTT, J.G., 1969. The Clyde Cairns of Scotland. In POWELL, T.G.E., CORCORAN, J.X.W.P., LYNCH, F.M. & SCOTT, J.G., 1969. Megalithic Enquiries in the West of Britain, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 175-222.

SCOTT, W., 1933. The chambered tomb of Pant y Saer, Anglesey. Archaeologia Cambrensis 38, 185-228.

SHARKEY, J., 2004. The Meetings of the Tracks: Rock art in Ancient Wales. Llanrwst: Carreg Gwalch.

SKINNER, J. Reverend, 1802. Ten Days Tour through the Island of Anglesey (reprinted with introduction by T. Williams, 2004).

SMITH, C.A. & LYNCH, F.M., 1987. Trefignath and Din Dryfol: The Excavation of Two Megalithic Tombs in Anglesey, Cambrian Archaeological Monographs, No. 3, Cardiff.

TILLEY, C., 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments, Oxford. Berg.

TILLEY, C. & BENNETT, W., 2001. An archaeology of supernatural places: the case of West Penrith. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 7, 335-62.

WILLIAMS, W. W. 1867. Mona Antiqua. Cromlech, Bodafon Mountain in Archaeologia Cambrensis, Third Series No. 52, 1867. pp 344-6.

WOODS, M., OWEN, A. & NASH, G.H., 2024. Illuminating Anglesey: Echoes of a later prehistoric ritualised landscape at Bedd y Foel. Current Archaeology 414, 46-51.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation