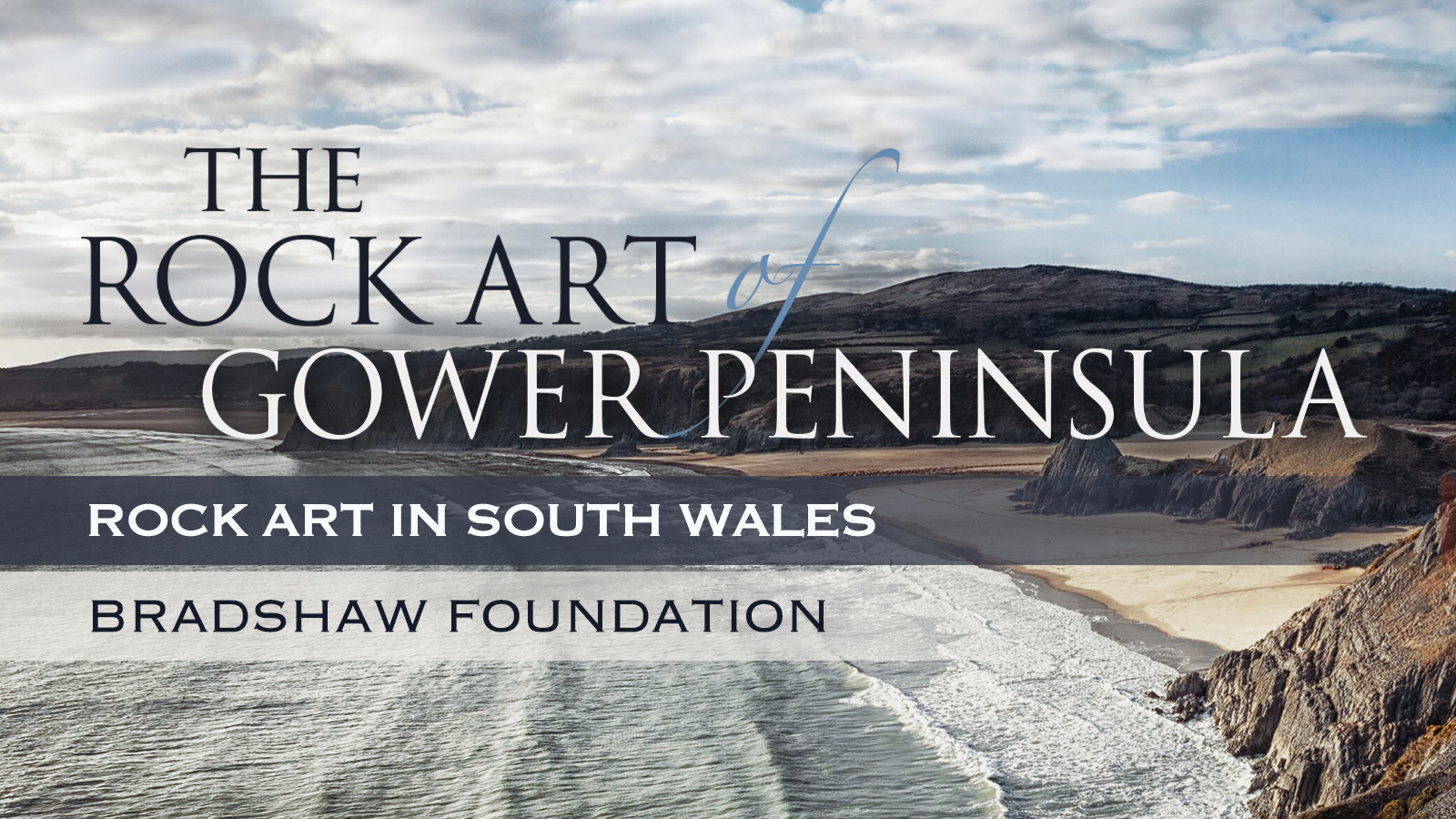

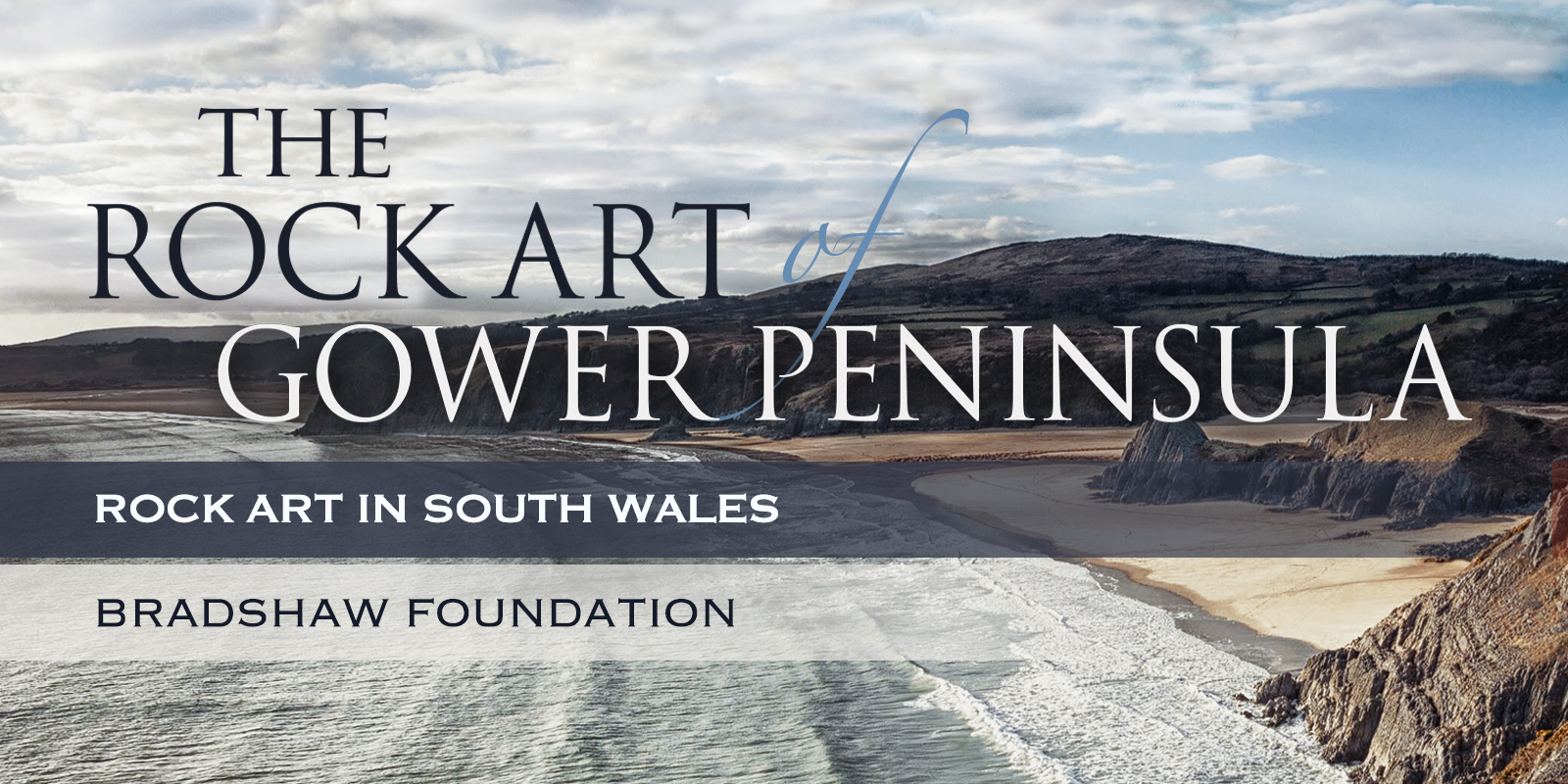

Discovered by archaeologist Dr George Nash, a wall carving on the Gower Peninsula in South Wales may prove to be one of Great Britain's oldest examples of rock art. The carving of a speared reindeer is believed to have been created by a hunter-gatherer in the Ice Age more than 14,000 years ago.

In a recent Press Release 'Minimum U-Series date makes Welsh discovery the oldest rock art in the British Isles (and North-western Europe)', the new minimum date of 14,505 + 560 years BP may confirm this.

The Archaeological Team:

George Nash,

Department of Archaeology & Anthropology, University of Bristol

Peter van Calsteren,

NERC-Open University Uranium-series Facility, Open University

Louise Thomas,

NERC-Open University Uranium-series Facility, Open University

Michael J. Simms,

Geomorphologist from the National Museum of Northern Ireland

Evidence of prehistoric occupation in Britain is abundant in many forms apart from rock art itself. However, the discovery in 2003 of engraved and bas-relief Upper Palaeolithic rock art in Church Hole Cave within Creswell Crags Gorge in Nottinghamshire proved that rock art was practiced in this harsh Ice Age environment, by bands of hunter/fisher/gatherer communities during the summer months, almost certainly for the same ritualistic reasons as their counterparts in a 'warmer' southern Europe.

During the Upper Palaeolithic, much of Britain and Ireland was covered by a thick blanket of ice, in places up to 2 km in thickness and it was considered that during this time there was little in the way of a human presence south of the ice margin. The Creswell Crags discovery was, however, to change this and ignite a new approach for the peopling of the British Isles during this harsh climatic period within our distant past. This was in the face of several claims regarding Upper Palaeolithic rock art, all of which were considered scientifically but eventually rejected.

In 1912 at Bacon Hole Cave on the Gower Coast, experts of the day found red streaks of haematite within one of the recesses of the cave (Figure 1). This turned out to be either natural haematite secretions or paint. In 1982 in the Wye Valley of South Herefordshire, researchers claimed to have found the outline of a bison and a red deer amongst other animals from Cave 5615 (Figure 2). Following much controversy, this too was rejected.

It was Creswell Craggs and its nearby caves within the gorge which provided more scientifically accepted evidence, with a series of Upper Palaeolithic mobile artefacts discovered during early 20th century excavations. These included Creswell's 'infamous' horse, that had been carved on a piece of rib bone (Figure 3), and a bird-like head on a human torso which had been carved on a piece of bone from a woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), a species which was considered to have been extinct in Britain by 15,000 BC. The presence of these rather exotic artifacts, along with a handful of other portable 'valuables' including perforated shell and stone, made for garment decoration, necklaces and pendants, occur against a backdrop of sometimes rapid climatic fluctuation when average summer temperatures at 12-13,000 BP were around between 0 and -5 degrees centigrade.

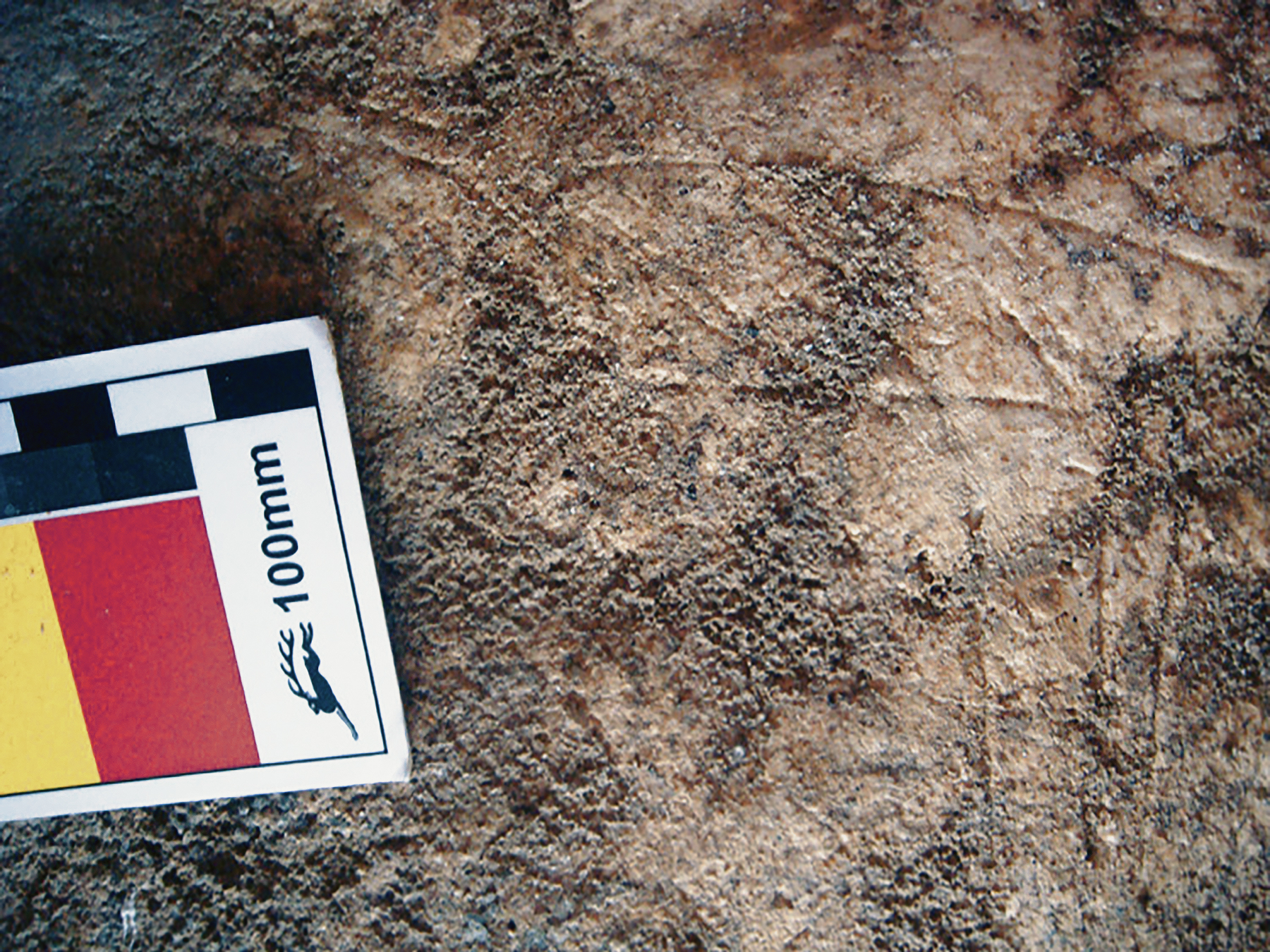

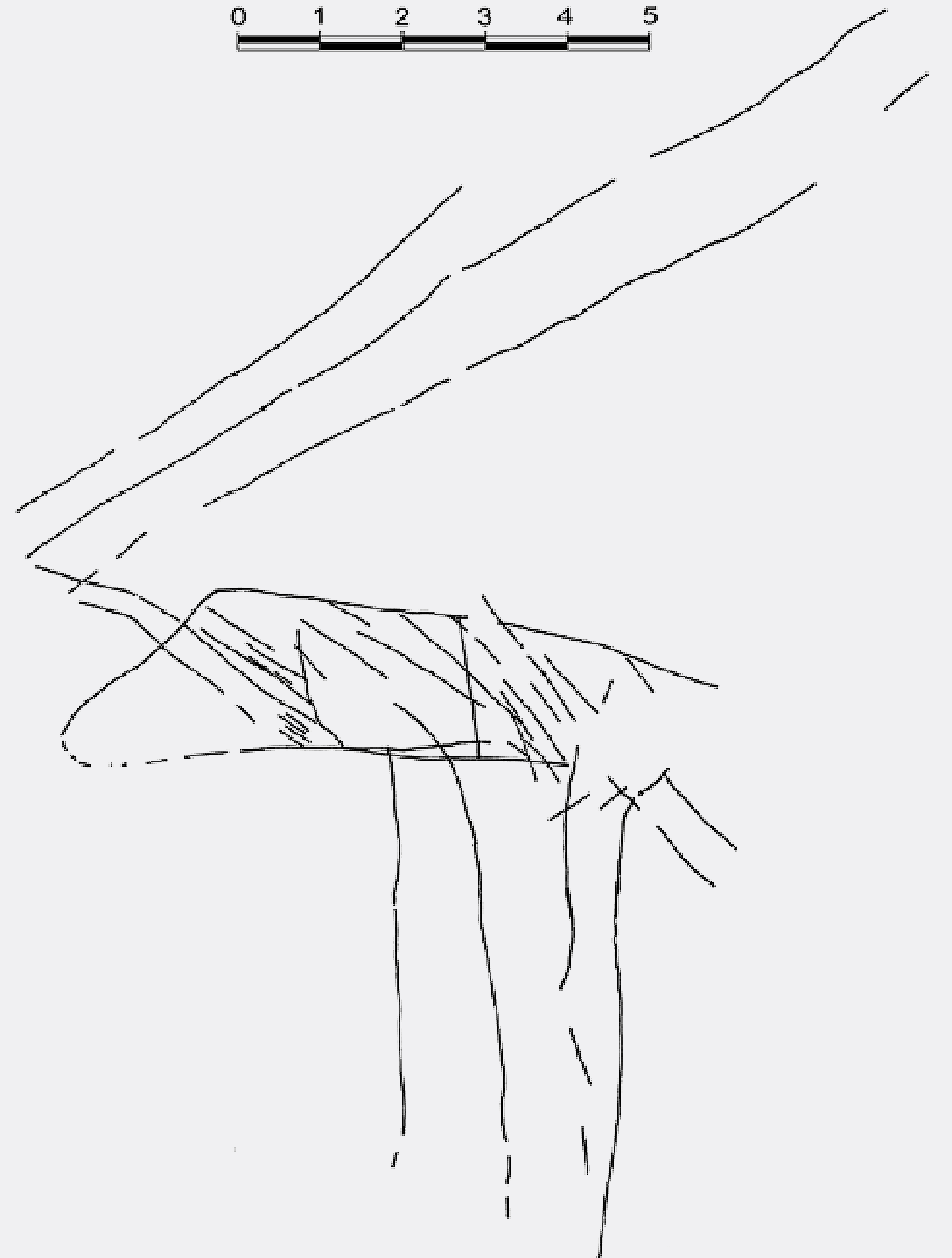

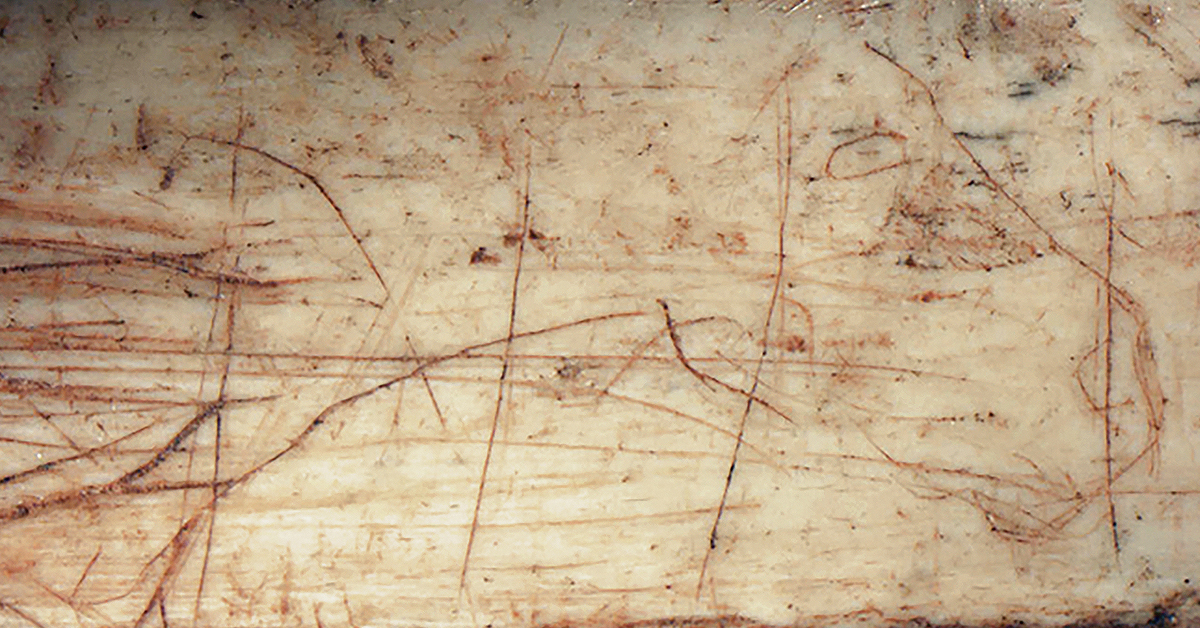

Photographs below: Figure 1: The mouth of the Bacon Hole sea cave, now overlooking the Bristol Channel. Figure 2: An unlikely bison, Pleistocene in date, located on a vertical panel from Cave 5615, near Symond's Yat in the Wye Valley Gorge, South Herefordshire. Figure 3: The infamous Creswell rib with an engraved horse. Figure 4: Creswellian-type points for Cheddar Gorge in Somerset. Figure 5: One of three bear claw scratches with the northern section of the cave. Figure 6: Central section of the engraving showing the torso and upper section of the legs.

In September 2011, Dr George Nash, as part of the team, was exploring the rear section of a limestone cave that stands within the eastern part of an inland valley on the Gower Peninsula, approximately 2 km north of the present coast line. The first excavation in this cave was undertaken during the mid to late 19th century when a large section of the cave floor was excavated. An array of flint tools, metal implements and pottery dating from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Bronze Age were recovered from the excavation, plus a significant Pleistocene faunal assemblage that included (extinct) elephant, giant deer, hyena, reindeer, woolly rhinoceros and wolf. Probably found within the upper stratigraphy was a small collection of domesticated bone including that of goat, pig and sheep that dated to the Neolithic or Bronze Age periods. Unfortunately, and typical of this time, no stratigraphic records were made. Accompanying these later prehistoric deposits was evidence of human burial, but again no archaeological clear records survive.

According to Dr George Nash, the majority of the lithic assemblage appeared to have originated from the Late Upper Palaeolithic and was similar to those found within trenching from a well-recorded excavation made, during the latter half of the 20th century, outside the entrance of the cave. Recovered from this excavation were more than 300 lithics, many of which were diagnostically similar to flint blades and points found at other so-called Creswellian cave sites at Creswell Crags and within Cheddar Gorge (Figure 4). In addition to this Late Upper Palaeolithic assemblage were two tanged points that were identified as dating to c. 28,000 BP suggesting that the cave had been subjected to a much earlier occupation at a time when the British Isles and most of north-western Europe were firmly gripped in an ice age (known as the Devensian). At this time, and until the glacial retreat around 14,000 BP, the Bristol Channel was then a seasonally lush landmass that extended to the present day north Devon and Cornwall coastline. Following the retreat of the Welsh ice sheets, groups of advanced hunter/fisher/gatherers would have utilised this sometimes hostile landscape, seasonally occupying many of the caves that are cut and shaped into the limestone Accompanying these small self-contained communities were herds of large migratory herbivores that included bison, elk, horse, mammoth and reindeer.

In 2007 the cave was explored by members of the Clifton Antiquarian Club from Bristol in search of rock art. The first visit resulted in the discovery of several cave bear (possibly Ursus arctos) claw scratches that were made following a probable hibernation episode (Figure 5). Possible engraved geometric patterns were also found within an antechamber, located north of the main gallery. However, the limestone throughout the cave is traversed by innumerable small-scale natural fractures and it was eventually considered to be a natural phenomenon.

In 2010 a further visit to the cave on the 18th September resulted in the discovery of a cervid, interpreted by Dr George Nash as a reindeer. This was engraved on a vertical panel inside a discrete niche, located north-east of the main gallery. This near-hidden engraving is the first clear evidence of Pleistocene rock-art in Wales and only the second discovery of Pleistocene rock art in Britain.

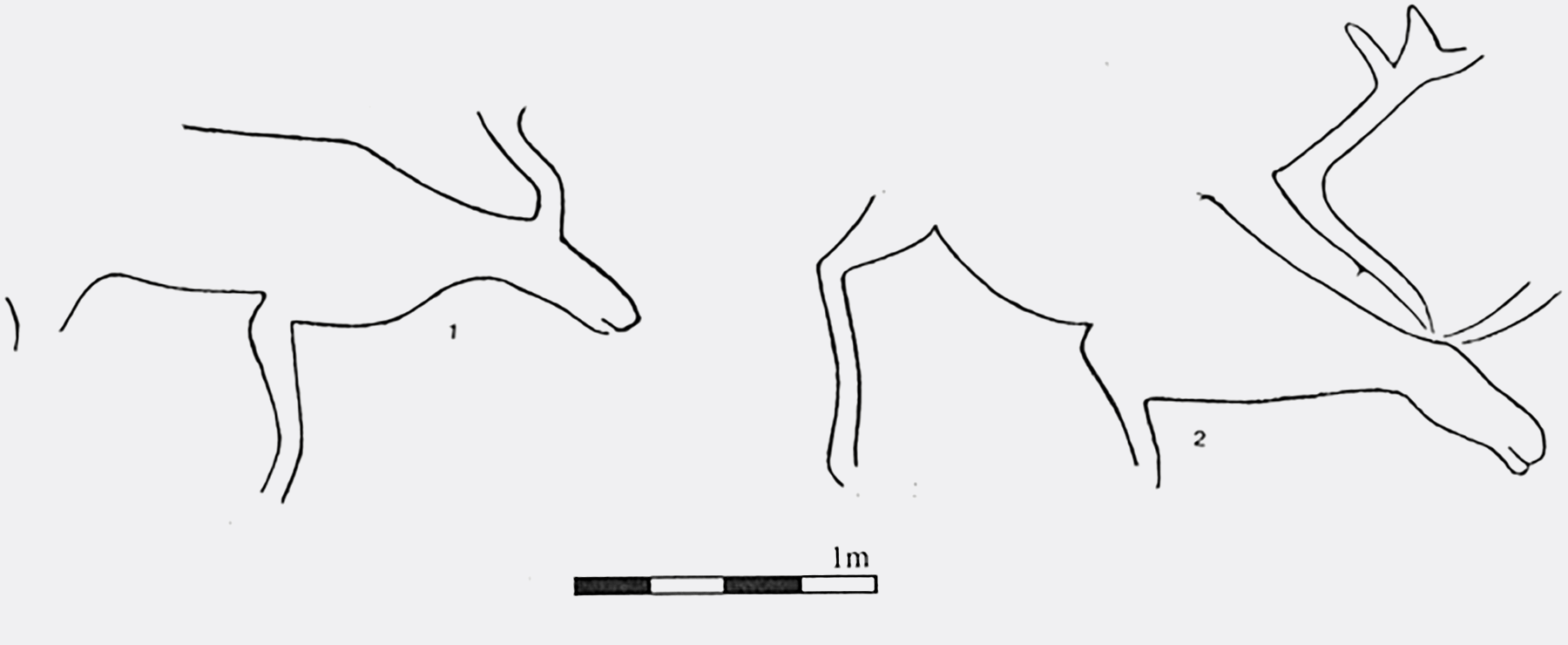

The stylized side-on view figure, measuring approximately 15 x 11cm, was carved using a sharp pointed tool, probably flint, and has a number of characteristics that resemble carved reindeer found elsewhere in north-western Europe. The niche was so tight that conventional cameras could not be used and therefore a series of overlapping images were made (Figure 6).The elongated torso has been infilled with irregular-spaced vertical and diagonal lines. A single vertical line appears to extend outside the area, between the torso and the antler set, representing a possible spear.

Several internal diagonal lines extend below the lower section of the torso, merging to form three of the four legs; the longest measuring 4.5cm. Incorporated into the left side of the torso and continuing beyond is the head (or muzzle) of the reindeer comprising a semi-circular snout, chin and mouth. Above the muzzle is a thin rectangular block on which three lines extend to the right forming a stylised antler-set (Figure 7). These various straight lines are cut into a weakly botryoidal calcite flowstone surface which has effectively sealed and covered any fractures in the limestone surface beneath. Any fractures developing subsequently on this flowstone would be influenced by its botryoidal form and hence show at least some degree of curvature. This is not the case and it is this contrast, between the straightness of the engraved lines and the curved nature of the relief on the flowstone that eliminates any possibility that the figure might be a chance configuration of natural fractures.

A tracing showing the simple lines of an engraved reindeer from Sagelva in Nordlamd

In April 2011 members of the NERC-Open University Uranium-series Facility extracted samples from the surface on which the engraving was engraved for Uranium Series dating, along with a sample from a section of flowstone that covers part of the reindeer's muzzle (Figure 9). A single date has revealed that this engraving was executed prior to a flowstone deposit which dates to around 12,572 + 600 years BP.

A further sample of the flowstone was taken left of the muzzle in July 2011. This sample may provide corroborative evidence of the age and confirm the absolute youngest age when the flowstone initially developed over the reindeer. The samples of the calcite underlying the engraving showed open system behaviour and an age could not be calculated.

An assessment of the cave and its wealth of discoveries made so far are at an early stage of research. An accurate plan of the cave using 3D laser scanning technology is on-going; this technique may detect more rock art and will give the first acute plan of the cave. As part of next phase of the project, the reindeer will be recorded in greater detail and the hunt for more rock art will continue, but for now a tracing (Figure 10) from the many images digitally taken will suffice.

Following this phase a management plan will be produced in order to assess the archaeological potential and secure the caves long-term future. As part of the logistical support, Elizabeth Walker, Curator of Palaeolithic & Mesolithic Archaeology from the National Museum of Wales has been gathering data from previous excavations and it is hoped that this information will form the basis of a much wider project that will reveal more than just a moment in time when a hunter/fisher/gatherer scratched with his or her right hand an image of a reindeer!

The Research Team includes Project leader and prehistoric rock art specialist Dr George Nash (University of Bristol), Dating team Dr Peter van Calsteren (Open University), Dr Louise Thomas (Open University) and Geologist and Cave Geomorphologist Dr Mike Simms (National Museums Northern Ireland).

Dr George Nash is an Associate Professor and currently lectures part-time at the Geosciences Centre, University of Coimbra (IPT), Portugal. He is a member of management and academic committee and lectures architectural and landscape theory, prehistory and art, excavation and European heritage planning legislation and policy. Prior to this, George lectured at Bristol University, between 1998 and 2016. Here, George ran the final two years of a part-time degree, with also input to the fulltime BA and MA in Landscape programmes. At IPT George is responsible for MA/PhD supervision for undertakes research.

Dr George Nash is a member of the Rock Art Network, the Network, established by the Getty Conservation Institute and the Bradshaw Foundation, comprises individuals and institutions committed to the promotion, protection, and conservation of rock art globally.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ British Isles Prehistory Archive

→ British Isles Introduction

→ Stonehenge

→ Avebury

→ Kilmartin Valley

→ The Rock Art of Northumberland

→ Rock Art on the Gower Peninsula

→ New rock art discoveries in the Peak District National Park

→ Painting the Past

→ Church Hole - Creswell Crags

→ Signalling and Performance

→ Cups and Cairns

→ Ynys Môn, North Wales

→ Bryn Celli Ddu

→ Remembering Stan Beckensall

→ The Prehistory of the Mendip Hills

→ The Red Lady of Paviland

→ Megaliths of the British Isles

→ Stone Age Mammoth Abattoir

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network