Ancient Rock Art up close

Ancient Rock Art up close

A few days exploring Andalucia’s painted caves

George Nash

Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool, UK

Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool, UK

Proposal, preparation and prospection

In early February 2025, I, alongside a team from the Bradshaw Foundation, was granted unprecedented access to four significant cave sites in Andalucía, southern Spain (Figure 1). The primary objective of this visit was to deepen the team's understanding of the complex chronological and technological methods used in cave archaeology, as well as to address the conservation challenges faced in this region of southern Europe. The visit was organized by Dr. Hipólito Collado Giraldo, a senior member of the First Art Team, along with cave researchers Dr. Pedro Cantalejo Espejo (and his son, Pedro Cantalejo Espejo), Dr. Luis Efrén Fernández, Dr. Yolanda del Rosal and cave owner and researcher Tomás Bullón. The itinerary included visits to the "El Cantal" cave system, which comprises Higuerón, La Victoria, and El Tesoro caves, located in Rincón de la Victoria, Málaga. One of these caves contains the oldest known examples of rock art in Andalucía.

Next, we visited the renowned Nerja Cave system, situated in the town of Nerja. Here, Dr Luis Efrén Fernández, the head of conservation at Nerja, provided us with access to sections of the cave where Upper Palaeolithic paintings are found on calcite curtains in concealed areas of the cave system. Notably, the Nerja cave system is among the largest in Andalucía. Our final visit took us to the spectacular Cueva de la Pileta Cave in Benaoján. This inland cave system is home to some of the most impressive painted and engraved panels in southern Europe. Once again, Tomás Bullón, the cave owner, facilitated our access to restricted areas of the cave not accessible to the public.

Accessing these sites for research purposes is often a challenging endeavour, especially when confronted with language barriers, differing personalities, perspectives, and the physical distance between one's home and the site. However, when circumstances align favourably, these obstacles seem to vanish. The arrangements for these visits (and the necessary permissions) were made possible by my dear friend and First Art colleague, Dr. Hipólito Collado Giraldo, who has been instrumental in facilitating such access. Prior to this expedition, I had the privilege of visiting all four sites during my tenure as a scientific researcher and presenter for an American production company filming a series on archaeology and rock art for the Discovery Channel in mid-to-late 2022.

Additionally, about 20 years ago, I led a group of students to the Cueva de la Pileta during my time as a lecturer at the University of Bristol. Although I was somewhat familiar with the sites, my roles as a lecturer and researcher had never allowed me the time to fully explore the caves or engage in a comprehensive examination (or a conversation with various stakeholders) of the archaeological history, the methods used, and the long-term conservation responsibilities necessary for maintaining these sites for future generations.

It is important to note that each of the four caves present unique conservation challenges, though all are under strict monitoring and care. Furthermore, with regard to the artistic expression and style, each cave exhibits distinct characteristics, reflecting local and regional ancient traditions, techniques, and chronologies. These variations suggest that the artists (and their audiences) perceived and interacted with their environments in slightly different ways, as evidenced by the divergent subject matter and artistic styles found in caves such as Nerja and La Pileta (Figure 2 & Figure 3).

The methods used for the preparation and application of paintings and engravings also differ across the four sites, which further underscores the varying perspectives of the communities that created them. These differences may reflect not only artistic preferences but also the diverse ways in which different groups perceived and engaged with their surroundings.

Chronologically, the archaeological evidence in all four caves spans a broad temporal range (Figure 4). The rock engravings and paintings dated to the Upper Palaeolithic fall within five cultural periods – the Magdalenian (17,000 to 12,000 BP), the Solutrean (33,000 to 22,000 BP), the Gravettian (26,000 to 22,000 BP), the Aurignacian (43,000 to 28,000 BP) and the Châtelperronian (44,500 to 36,000). The Châtelperronian period bridges the Middle Palaeolithic with the Upper Palaeolithic. Note there are chronological and spatial overlaps, depending on what has been published – which is not helpful!

Artefacts, particularly stone tools, have been found that date back to a time when Neanderthal communities were actively utilising the southern Iberian landscape, where our cousins are usually assigned to the Middle Palaeolithic (although there are small enclaves in western and southern Iberia, where they manage to survive to around 28,000 years ago.

Sophisticated artistic production made by artists during the Upper Palaeolithic, found notably in Cueva de la Pileta, Cueva de la Victoria, and Cueva de la El Tesoro caves, also has a Neolithic and Early Bronze Age presence, as indicated by the discovery of Schematic rock art (Figure 5), along with burial remains, lithic tools, and pottery.

Art…but not as we know it

Before delving further into the archaeological history of each site and the rock art observed within them, it is important to clarify my perspective on the concept of "rock art" and its implications.

Fundamental to this essay, I have lifted from my DPhil. thesis, this:

...the term "art" will be used with precision, referring to a cultural, symbolic, and meaningful medium that serves an operative function in shaping and regulating the way humans organise and navigate their daily lives. Within these frameworks of control and regulation, however, there exists inherent ambiguity, as the nature of agency is to continually challenge and transform these structures. Such ideas resonate with concepts of structuration and cognition, as explored by the sociologist, Anthony Giddens, although I do not adhere rigidly to these theoretical frameworks. Instead, I argue that these mechanisms of control operate within a standardised set of rules that are intentionally rigid and constraining, serving specific purposes, much like those observed in contemporary non-Western hunter-gatherer societies. In this context, the conventional Western conception of art—as embodied in the romantic ideal of the artist as a singular, creative individual—fails to provide an adequate understanding of the social and cultural functions of prehistoric imagery. I have suggested that such a view overlooks the broader, often collective role of these images within their societal and symbolic contexts (Nash 2003).

Over the past 130 years, archaeologists have adopted the term "rock art" as a convenient label for a diverse range of markings, yet the precise meaning of this term remains somewhat ambiguous. The term was first coined in the late 19th century, shortly before and particularly after the controversial discovery of the painted sleeping bison imagery in Altamira Cave in northern Spain (Figure 6). Since then, it has been widely used to categorise various forms of prehistoric imagery, but the application of the term often raises questions. While I, too, use the term, there are occasions when I find it problematic to refer to certain non-figurative signs, motifs, or symbols as "art."

In previous discussions, I have argued that even a simple sign can embody a complex world, shaped by social, political, economic, and symbolic forces. To illustrate this point, one need only consider symbols such as the Christian cross or the Islamic star and crescent, which, while not necessarily artistic in the traditional sense, hold profound significance within their respective cultural and religious contexts (Figure 7). In the context of prehistory, I am particularly drawn to the humble cupmark, a non-figurative motif that appears in both early and later prehistoric contexts. Such signs, motifs, and symbols, particularly in Upper Palaeolithic cave or rock shelter settings, seem to extend beyond mere artistic display, functioning more as a means of conveying messages to specific members of a hunter-gatherer community. I would also add that the cupmark is found in a variety of archaeological and geographic contexts and across vast areas of the world. Are we looking at a universally understood symbol, like the Christian cross, but bridges both the Palaeolithic and later prehistoric periods – a time span of at least 35,000 years?

I base this interpretation on the assumption that not all members of these communities would have had unrestricted access to the deeper recesses of caves, where such art was often located. This restricted access likely imbued these spaces with a sense of exclusivity and power, with artists possessing unique knowledge regarding the application and interpretation of these signs. Furthermore, it is plausible that certain individuals—such as elders, elites, or initiates—played a key role in the creation of these images, either directly or indirectly. These roles likely mirrored those of storytellers in contemporary non-Western societies, individuals tasked with conveying moral lessons, rules, and cultural narratives, a function that resonates with the roles of religious figures in many modern world religions. In this way, the creation of rock art may have been a deeply communal and performative act, serving not only as an aesthetic expression but also as a medium for social, cultural, and spiritual communication.

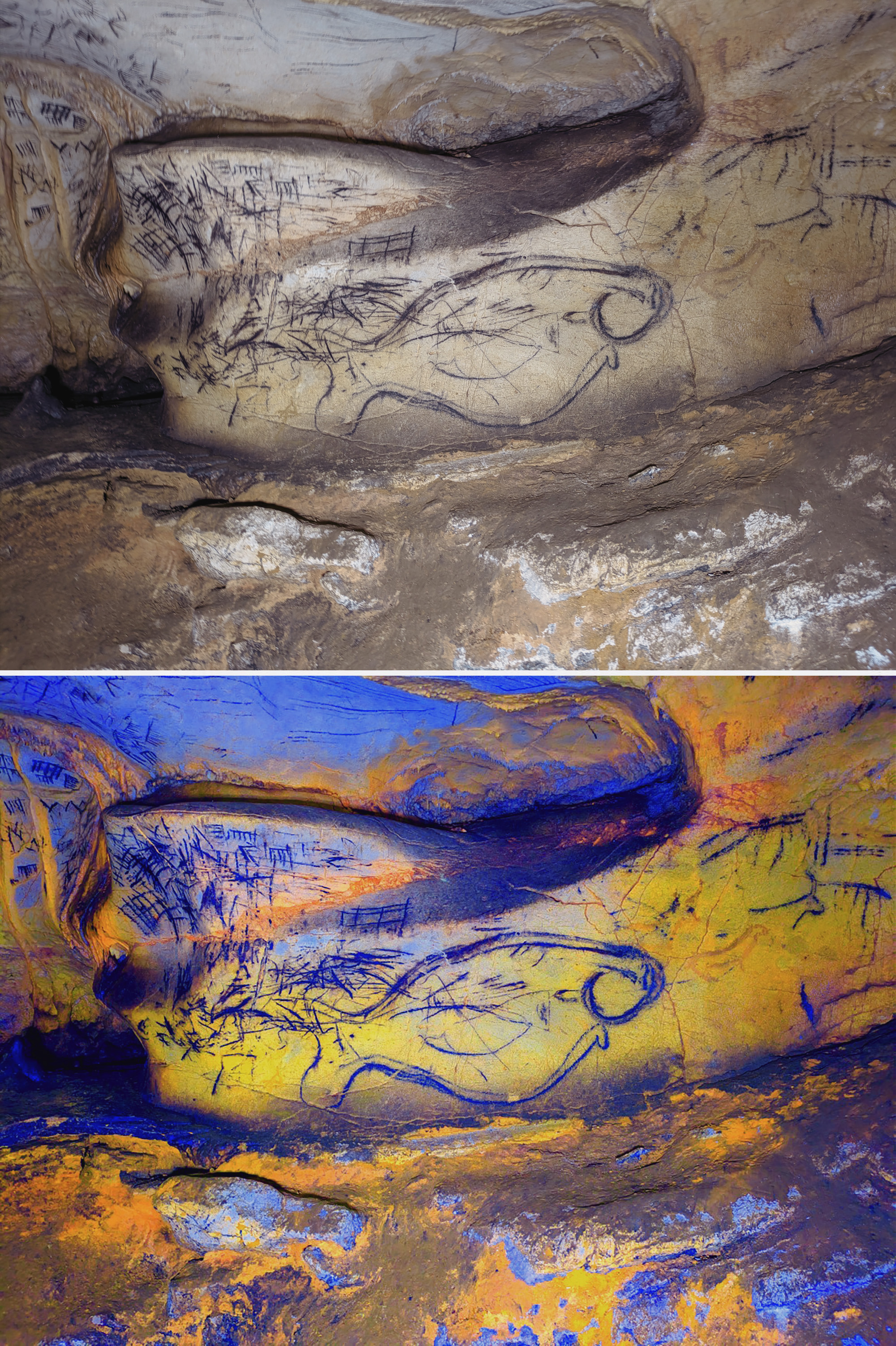

To avoid excessive elaboration, I will conclude by emphasizing that the term "rock art" encompasses a wide range of connotations and meanings; it should certainly not be dismissed as mere idle graffiti. As previously noted, the rock art from the four Andalusian caves is distinct, with each site reflecting slightly different ideologies, likely shaped by factors such as climate, environment, economy, social norms, and chronological context. While I have briefly addressed the value and significance of simple markings—an area of considerable depth with profound implications for contemporary society—let us now turn to figurative art, including the later-recognised schematic forms found across all four caves. There appears to be a running visual narrative present in all caves with various species of animal, painted and engraved in different styles but containing a universal theme – that is animal depictions are rarely complete (Figure 8 & Figure 9). Usually missing are limbs, rear and lower torsos, and sometimes, heads. Despite the missing attributes, animals from the Upper Palaeolithic are usually recognisable. This generic theme extends across much of Upper Palaeolithic Europe.

FIGURE 8 & 9

Upper section of a painted horse (missing lower torso and legs) emerging from the rock panel at Cueva de la Pileta (as a deity, spirit and used as a way of communicating a narrative to an audience, via a mediator – the artist?). Conventional photography and enhanced D-Stretch image

Upper section of a painted horse (missing lower torso and legs) emerging from the rock panel at Cueva de la Pileta (as a deity, spirit and used as a way of communicating a narrative to an audience, via a mediator – the artist?). Conventional photography and enhanced D-Stretch image

© George Nash

Anthropological and ethnographic evidence suggests that, in many cases, animal depictions may not be as straightforward as assumed. Scholars such as Christopher Tilley (1991) and Ian Hodder (1990) have described ancient engravings and paintings as ambiguous, embedded within complex social networks, and integral to narratives that are part of a broader performative context (see Nash, 2003). To illustrate this point further, let us consider an anecdote. I recall a moment when my esteemed colleague, Dr Christopher Chippendale, observed a "Big Man" (a tribal elder and painter) from the Northern Territories of Australia painting a crocodile onto an already intricate rock art panel. Unsurprisingly, the imagery was employed as a device to convey stories, often addressing themes such as community gender roles, moral dichotomies, and cycles of death and rebirth. When Chris inquired about the crocodile, the Big Man explained that it was not a crocodile, but a snake. Chris pointed out that the image clearly depicted a crocodile. The Big Man responded by affirming that, while it was indeed a crocodile, it was now a snake—the story had evolved, both spatially and chronologically. In a similar vein, when considering a painted horse from Cueva de la Pileta, what are we truly examining in terms of meaning and narrative? I ask the question, is a horse painting merely depicting a horse or is it something far more ambiguous and complex?

FIGURE 8 & 9

Upper section of a painted horse (missing lower torso and legs) emerging from the rock panel at Cueva de la Pileta (as a deity, spirit and used as a way of communicating a narrative to an audience, via a mediator – the artist?). Conventional photography and enhanced D-Stretch image

Upper section of a painted horse (missing lower torso and legs) emerging from the rock panel at Cueva de la Pileta (as a deity, spirit and used as a way of communicating a narrative to an audience, via a mediator – the artist?). Conventional photography and enhanced D-Stretch image

© George Nash

FIGURE 8 & 9

Upper section of a painted horse (missing lower torso and legs) emerging from the rock panel at Cueva de la Pileta (as a deity, spirit and used as a way of communicating a narrative to an audience, via a mediator – the artist?). Conventional photography and enhanced D-Stretch image

Upper section of a painted horse (missing lower torso and legs) emerging from the rock panel at Cueva de la Pileta (as a deity, spirit and used as a way of communicating a narrative to an audience, via a mediator – the artist?). Conventional photography and enhanced D-Stretch image

© George Nash

FIGURE 8 & 9

Upper section of a painted horse (missing lower torso and legs) emerging from the rock panel at Cueva de la Pileta (as a deity, spirit and used as a way of communicating a narrative to an audience, via a mediator – the artist?). Conventional photography and enhanced D-Stretch image

Upper section of a painted horse (missing lower torso and legs) emerging from the rock panel at Cueva de la Pileta (as a deity, spirit and used as a way of communicating a narrative to an audience, via a mediator – the artist?). Conventional photography and enhanced D-Stretch image

© George Nash

This exchange highlights an important point: early prehistoric rock art may also be part of a larger narrative, where only a single chapter or segment is represented in any given image. In the case of Cueva de la Pileta, for example, the painted horses—along with other motifs such as felines, fish, and gazelles—could be fragments of a more complex story, one that unfolded over time. In this sense, the horse paintings might represent specific "chapters" in a far-reaching narrative. Hodder (1990) considers the large megafauna, such as horses representing ‘maleness’ (although many horses depicted in the Iberian Peninsula of Upper Palaeolithic could also be female). Tilley (1991) argues that the act of engraving in dangerous places, such as the inner recesses of a cave system as being part of an initiation process, whereby one enters the inner cave system as a juvenile and later, emerging as an adult, following his or her marks on a cave wall or ceiling, be it a symbol or an animal.

While we may never fully understand the precise nature of these ancient visual narratives, it is essential to recognize that at least 800 generations have lived and passed around these caves since the paintings were first executed. The specific meanings of these images have undoubtedly been lost to history, although in some areas of the World, ancient stories displayed pictorially form part of a living tradition, a process that was studied by anthropologist Claude Leví-Strauss (1963, 1964,1973 1986). Leví-Strauss undertook a large study to record myths, legends and storytelling in Amazonia. Here, he noticed a clear formulaic in the structures of the narratives told. Could the oral tradition of storytelling possibly relate to a pictorial one, especially on panels that were created in early prehistory? Alas, we are left to speculate on the rhetoric and aesthetics of the artistic endeavour of our ancient ancestors sought to convey, bearing in mind that the true significance of these images may forever remain beyond our grasp.

So, onto the caves

During our expedition, the Bradshaw Foundation Team and I explored four distinct cave environments, each cave exhibiting its own unique characteristics and integrity, which were partially reflected in the imagery adorning their walls. Notably, all four caves shared a common pattern in the distribution of cave art, which was typically located in the rear sections of the caves, often concealed within niches, small crevices and calcite curtains. This suggests that the artists were likely concerned with the visibility of their work and the intended audience.

A key challenge in our investigation was determining the relationship between the artwork's placement and the original entrances of the caves. It is important to emphasise that the current cave entrances are not representative of those from 15,000 to 30,000 years ago. During that period, the entrances would have been situated much further forward than they are today, due mainly to erosion and seismic activity. Moreover, accessing the areas with preferred panels would have been difficult and perilous, with minimal lighting and uneven, unstable surfaces.

FIGURE 10 & 11

Guide markers that are strategically-placed in areas of a cave system in order to move people safely from the entrance to the ritual areas of the cave. Markers are made from multiple finger dots (from Cueva de la Victoria) and by a projected mark (from Cueva del Nerja) (no scales used)

Guide markers that are strategically-placed in areas of a cave system in order to move people safely from the entrance to the ritual areas of the cave. Markers are made from multiple finger dots (from Cueva de la Victoria) and by a projected mark (from Cueva del Nerja) (no scales used)

© George Nash

FIGURE 10 & 11

Guide markers that are strategically-placed in areas of a cave system in order to move people safely from the entrance to the ritual areas of the cave. Markers are made from multiple finger dots (from Cueva de la Victoria) and by a projected mark (from Cueva del Nerja) (no scales used)

Guide markers that are strategically-placed in areas of a cave system in order to move people safely from the entrance to the ritual areas of the cave. Markers are made from multiple finger dots (from Cueva de la Victoria) and by a projected mark (from Cueva del Nerja) (no scales used)

© George Nash

In the case of Cueva de la Pileta, it appears that artists employed red haematite markers on specific rocks between the entrance and the areas containing rock paintings and engravings, likely to guide individuals safely through the cave system (on at least three levels). If this hypothesis is correct, I would classify this imagery as being functional/informative rather than as rock art (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

The four caves that we visited are, but a small sample of the numerous caves found throughout the limestone regions of southern Spain, spanning from Cadiz in the southwest to Barcelona in the northeast (Cantalejo & del Mar Espejo, 2014; Leroi-Gourhan 1968; Lawson 2012; David 2017). Despite the observable variations in artistic style, subject matter, and chronology, these caves collectively adhere to a discernible set of patterns, regardless of whether they are situated inland or along the coast.

- First, Upper Palaeolithic settlements (used for domestic purposes) are typically located at the entrances of caves.

- Second, the rock art is consistently found in discrete areas within the cave, often in the more inaccessible rear sections or hazardous locations, such as the descent to deeper levels within the main cave areas in Cueva del Nerja and Cueva de la Pileta. Additionally, artwork is frequently located in small, secluded niches and cracks, which may have functioned as personal or familial shrines, for lack of a better term (e.g., Figure 12 & Figure 13).

- Thirdly, the distribution of these artistic panels spans a period of approximately 20,000 to 30,000 years – a substantial amount of time where both technology and art changes.

- Finally, the later occupation of these caves, primarily between the Mesolithic and Iron Ages, tends to be restricted to the cave entrances, with successive communities generally avoiding the deeper, more perilous inner recesses. It is likely that these dark and dangerous sections of the caves were known to later prehistoric populations but were intentionally avoided or respected.

In my own experience, I have observed little or no evidence of superimposition by later prehistoric artists, although it is possible that such instances did occur. What is more clearly evident, however, is the presence of later prehistoric burials, typically dating to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, in all the caves we visited. These burials are generally accompanied by grave goods, most commonly pottery (Figure 14).

The brief descriptions of each cave that follow are intended to provide the reader with a clearer understanding of the points discussed above. For those interested in further exploring these topics, I recommend consulting the seminal works of André Leroi-Gourhan (1968), Clottes & Lewis-Williams (1998), David (2017), David & McNiven (2017), and Lawson (2012), among others. For in-depth accounts [monographs] of the four caves we visited, the following sources are recommended: for La Victoria and El Tesoro, see Cantalejo et al. (2007) and Cantalejo & del Mar Espejo (2014) [in Spanish]; for Cueva de Nerja, refer to Gimenez (1965), Cantalejo & del Mar Espejo (2014) [in Spanish], and López del Hierro (2016) [in English]; and for Cueva de la Pileta, consult Gimenez (1965) [in English] and Bullón Giménez (2006) [in Spanish].

Cueva del Tesoro

This extensive rare marine cave system, known as the Cave of Treasures, has yet to be fully explored. The cave was formed over many thousands of years, creating a series of passages, niches, galleries and several caverns. The ceilings, floors and walls have been eroded smooth from running seawater, when the cave system was below sea level (Cantalejo et al. 2007). Sometime during the late Quaternary epoch, the landform around the cave began to rise, creating a limestone pavement with deep gullies and cracks. The landform, found elsewhere in limestone areas, allowed freshwater to seep through the gullies and cracks, into an already formed cave system to create a unique cave environment that included large speleothem formations (stalactites and stalagmites), especially where the overlying bedrock was weak.

Prior to 1918 to a visit by Henri Breuil, the cave system had been badly treated, mainly due to a legend that involved hidden gold. The first excavation, undertaken by Professor Laza Palacio, uncovered a ceramic lamp in which six gold coins from the time of Ali ibn Yusuf (AD 1083-1143) were found. Later, Antonio de la Nari, spent nearly 30 years searching for the lost treasure. In his quest, de la Nari opened up a number of passages and galleries with dynamite. Alas, he died in 1847 from a dynamite explosion in the cave.

Following a visit by Abbé Breuil, he described this site and others in the vicinity in an article published in the French journal L'Anthropologie (Vol. XXXI), entitled New Paleolithic Ornate Caves in the Province of Málaga. In the paper, Breuil documents the remains of cave paintings and associates them with imagery found in Cueva de la Pileta, referring to them as ‘red signs’.

In the late 1950s, a small excavation was conducted by Manuel Laza and Simeón Giménez Reyna. However, the excavation revealed disturbed stratigraphy, likely due to treasure hunting activities by Antonio de la Nari. Despite the disturbance, Laza and Giménez uncovered Neolithic remains, including pottery fragments, numerous lithic tools from the Late Upper Palaeolithic (LUP), particularly from the Solutrean period (22,000 to 17,000 BP), and both human and animal remains.

The current cave director, Pedro Cantalejo, and his son initially guided us through the public areas of the cave. It is important to note that this site is a show cave with designated access for individuals with disabilities. Over the years, sections of the cave floor have been concreted, and a sympathetic lighting system has been installed. However, Pedro and his son took us off the beaten path, leading us into areas beyond public access, where we were able to view some of the exquisite paintings and engravings hidden away in various side passages and niches (Figures 15, 16, 17, 18). While several areas remain unexplored, it is likely that closer examination of the walls and ceilings may reveal additional hidden artworks.

What we did observe were several hand impressions and lines, likely made by a juvenile who ran their pigment-stained fingers down the cave wall. These impressions are of Upper Palaeolithic origin. We were also shown a series of finger dots made from red hematite. These simple impressions likely served as markers to guide individuals through the cave system. Among the most unusual figures within the cave was a painted cervid, possibly a red deer. This figure, common in Upper Palaeolithic art, was partly-painted using natural cracks in the rock surface (Figure 19 & Figure 20).

Cueva de la Victoria

Upon emerging from the subterranean environment of Cueva del Tesoro, Pedro (senior) led our group towards Cueva de la Victoria, located approximately 140 m to the west, within the [designated] Mediterranean Prehistoric Park. The descent into the cave system was achieved via a 6-7 m vertical ladder, followed by a crawl through a narrow passage leading into the main chamber (Figure 21 & Figure 22). Although it remains unconfirmed, it is highly probable that Cueva de la Victoria is physically connected to the neighbouring Cueva del Tesoro, as both the eastern and western extremes of both caves are relatively close.

The cave contains both Upper Palaeolithic rock art and Neolithic Schematic art, the latter being distributed across the main chamber, yet not directly intermingled with the former. Associated with the Schematic art are indications of human internment, accompanied by pottery fragments. The Schematic art shows possible stylised human figures, concentrated on several panels along the southern side of the main gallery (Figure 23 & Figure 24). In addition, and close by to the Schematic panel, close to an intermate elevated niche was a handprint (along with projected [spit] markings), believed to date to the Early Upper Palaeolithic (Figure 25 & Figure 26).

The cave was discovered in 1918 by Henri Breuil during one of his many visits to the Málaga region. In 1924, Breuil published an account of his expedition, which included Palaeolithic naturalistic figures discovered in the adjacent Cueva del Higuerón. From 1941 onwards, Simeón Giménez conducted excavations throughout the Málaga region and was responsible for investigating the caves of Cueva de la Pileta and Cueva del Nerja, as well as Cueva de le Victoria (Giménez 1958, 1965).

The Upper Palaeolithic rock art is believed to date to two distinct phases: the Aurignacian and Gravettian periods, spanning from approximately 42,000 to 23,000 years before present (BP). This artwork includes painted finger dots of varying sizes, which may have served as guide markers, as well as positive and negative handprints, airbrushed surfaces, and projected spit marks, all created using red hematite (see Collado Giraldo 2018). Notably absent from these early artistic expressions is naturalistic imagery. Many scholars working with this material suggest that such forms of visual expression may predate figurative Upper Palaeolithic art and could have been created during a transitional period between the last Neanderthal groups and the first Early Modern Human communities in this region of the Iberian Peninsula (e.g., Garcês & Nash 2024). However, it is important to approach this theory with caution, as the boundaries of the so-called transitional period fluctuate depending on newly obtained dating evidence.

At this juncture, I will now take a bold stance and propose that simple symbolic signs, such as finger dots, handprints or stencils, and projected spit marks (along with their associated complex narratives and meanings), were initially employed by Neanderthal communities. These early practices likely influenced the incoming groups of Early Modern Humans. This interaction probably took place during a crucial period in our early history, approximately between 50,000 and 42,000 years ago. – there we are, I’ve said it!

The Schematic phase, dated between 6,400 and 4,500 BP, includes approximately 100 stylised human figures painted in white, located on two opposing walls within the main chamber. This sacred space is known to have contained several burials from the Neolithic period. It is plausible to consider that the burial practices and the Schematic motifs are contemporary, with the art reflecting themes of death and burial—an idea found not only in natural caves but also in dolmens and passage graves throughout Iberia (Garcês et al., 2022).

Following our exploration of the main chamber, we ventured down a side passage and up and down several laddered acescents and descents to reach another large chamber. It was within this area of the cave that more finger dots to present. Within the chamber, Pedro’s team had been excavating a small area, revealing a shallow stratigraphy which clearly showed the presence of Early Modern Human activity, extending at least 30,000 years. Several metres away from the excavation was our ascent, back into the world we live (Figure 27 and Figure 28).

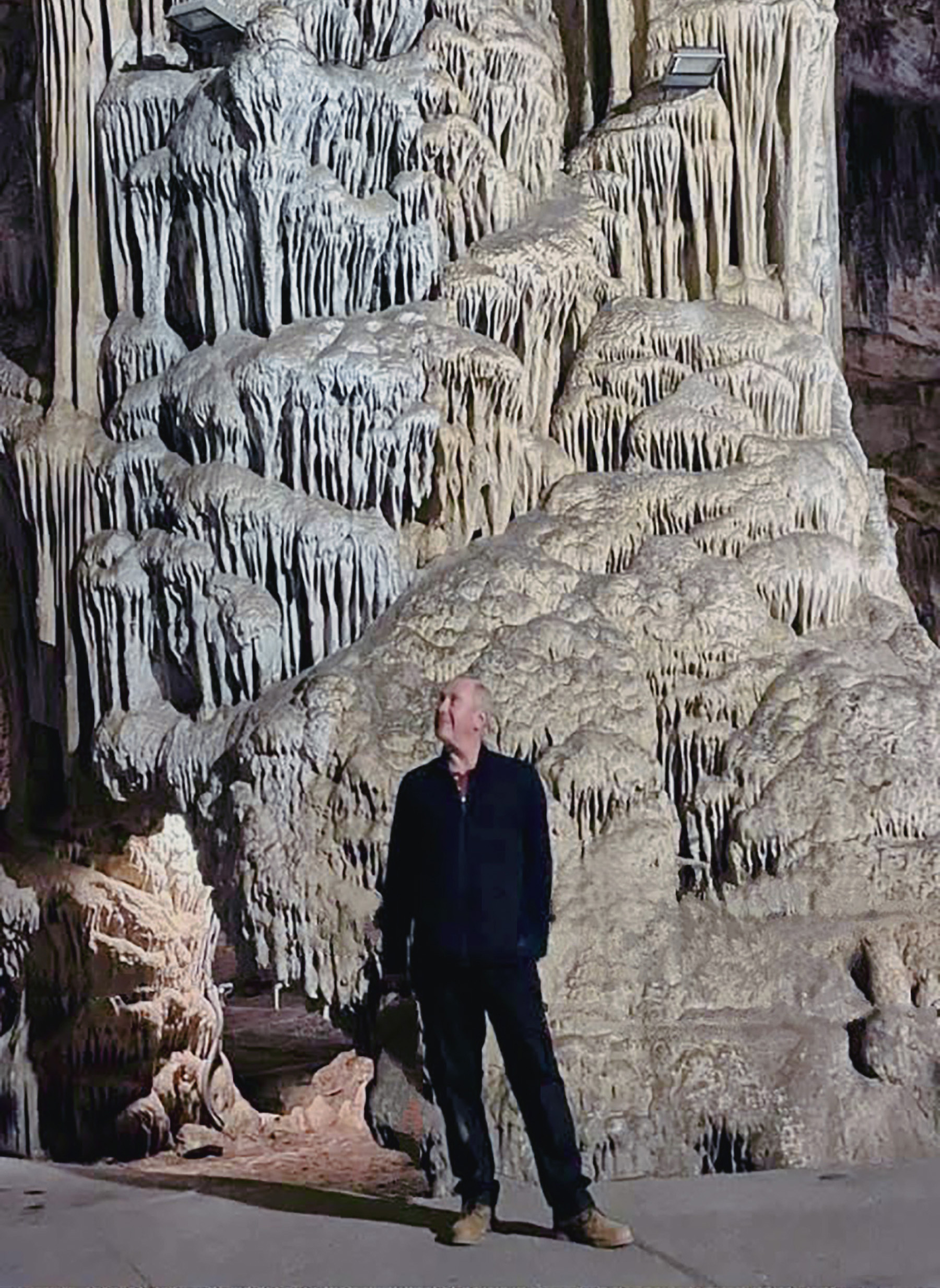

Cueva del Nerja Cave system

Following our visits to the caves in Rincón de la Victoria, the Bradshaw team proceeded eastward along the coastal road towards the monumental caverns of Cueva de Nerja. This vast cave system, which extends for five kilometres, is classified as a show cave and features a visitor-friendly route traversing various cave levels. While its profound archaeological significance cannot be overlooked, the sheer natural beauty of the cave system alone would justify its status as a site of exceptional interest (Figure 29). Our guides for this visit were Dr. Luis Efrén Fernández, the cave conservator, who has authored numerous scholarly works on the science of cave art in the region and cave biologist and researcher at the Nerja Cave Foundation, Dr. Yolanda del Rosal.

Cueva de Nerja is a highly complex cave system, consisting of a series of interconnected passages, chambers, and caverns. Since its discovery in the 1960s, the cave has become a major tourist destination. The system was first uncovered on January 12, 1959, by five schoolboys who entered through a narrow sinkhole, later named "La Mina." This access point is one of two natural entrances into the cave system, with a third entrance created in 1960 to facilitate visitor access. Presently, visitors enter the cave system through a purpose-built information hub.

The cave is divided into two main sections: Nerja I and Nerja II. Nerja I is the public gallery, easily accessible via a concrete pathway and steps. Nerja II, discovered in 1960, comprises the upper gallery and remains closed to the public. Additionally, Nerja II includes a newly discovered gallery, which was identified in 1969. Access to Nerja II and its other sections is particularly challenging. In February 2012, a significant discovery was made in this area, when a possible figurative panel containing paintings of extinct Mediterranean seals was reported. These paintings were hypothesized to have been created by Neanderthal artists approximately 42,000 years ago (Figure 30). However, the dating of these paintings was controversial, as the date was derived from a haematite deposit incorporated into a stratigraphic layer beneath the panel. This indirect dating method, based on organic material found in the same deposit, suggested a 42,000 BP age (see Macerlean, 2012). While the dating remains contentious, it represents a promising approach to understanding the chronology of potential early rock art activity.

Beyond this discovery and the evidence of Early Modern Humans, Cueva de Nerja also possesses a complex geological history. Approximately five million years ago, during the Miocene epoch, surface water infiltrated fissures and cracks in the limestone pavements above, forming an extensive cave system with a large cavern. Successive seismic activity during the Holocene redirected the surface water flow, contributing to the formation of giant speleothems.

Regarding the archaeological evidence, aside from the Neanderthal rock art, human activity within the cave spans the Solutrean period (c. 25,000 BP) through to the Bronze Age. The archaeological record includes human remains, with burials accompanied by grave goods, as well as palaeoenvironmental evidence such as faunal remains (including mammal and fish bones, marine shells, gathered carbonized seeds, and lithic tools). The rock art itself dates from approximately 25,000 to 4,000 BP and is believed to have been created by seasonal communities of hunter-fisher-gatherers, and later, by farming communities. Based on the dating evidence, these communities appear to have occupied the cave throughout the year, utilising the space not only for habitation but also for the creation of art, likely using imported haematite (as the cave itself does not contain large deposits of natural haematite).

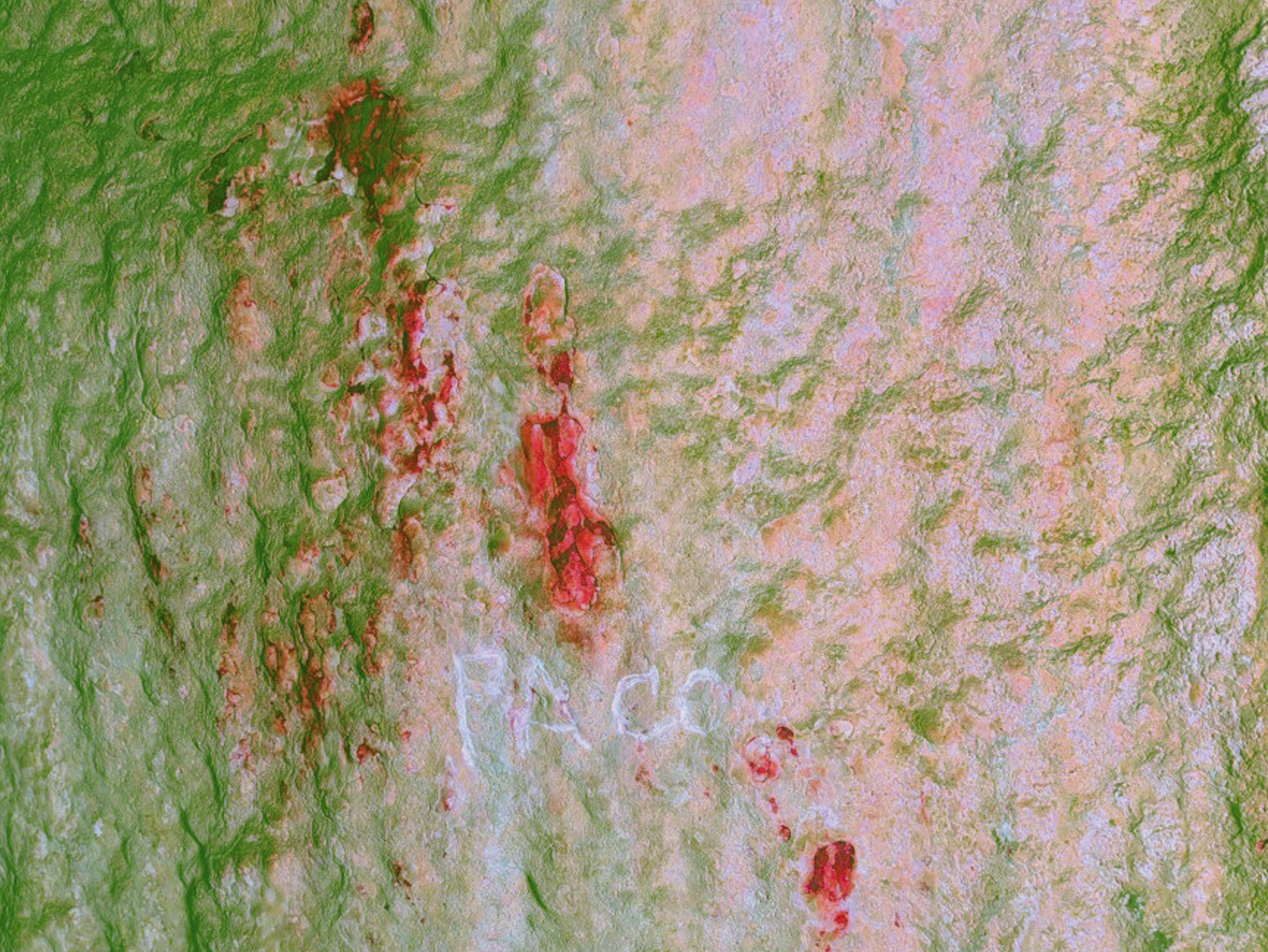

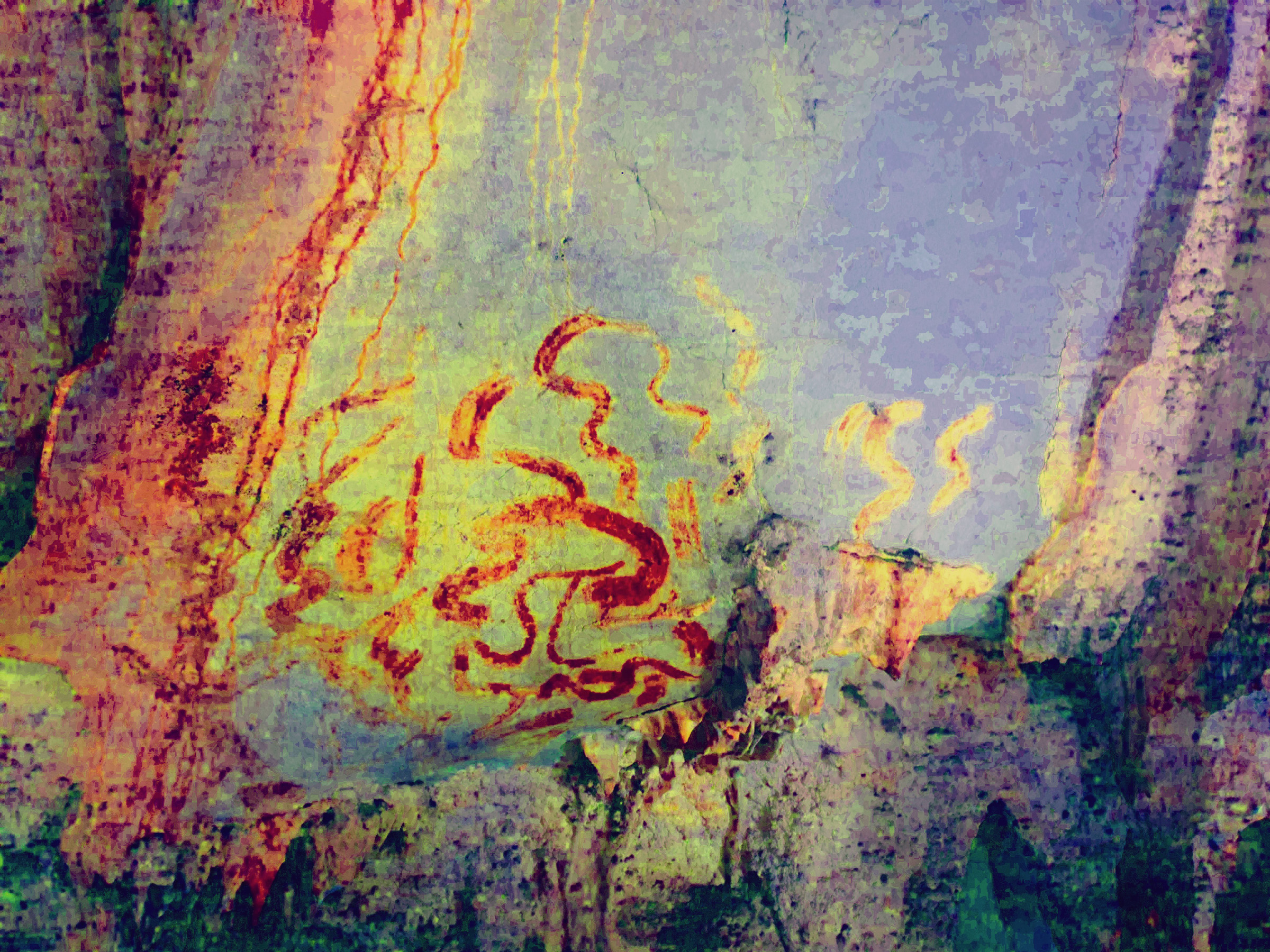

FIGURE 31

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

FIGURE 32

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

FIGURE 33

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

FIGURE 34

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

FIGURE 35

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

Various forms of artistic endeavour (with their D-Stretch counterparts), present on speleothems and rock surfaces throughout the periphery walling of the cavern

As previously mentioned, Dr. Luis Efrén Fernández served as our indispensable guide during the visit, and we were fortunate to access areas of the cave not available to the general public. Our primary objective was to examine the ancient imagery, which had been painted in the more discreet sections of the cave. A notable observation during the visit was the prevalence of both figurative and non-figurative imagery, much of which had been painted on speleothem curtains that adorned the side walls at various levels of the cavern. In addition to these hidden artworks, we also encountered a series of finger dots, which likely served as guide markers for ancient communities, facilitating safe access to various areas within the cave system. This discovery further underscores the intricate relationship between the cave's geological formations, the artwork, and the practical use of the cave by its ancient inhabitants.

Access to the various painted sections of the cave was off-piste, usually behind conservation barriers or hidden on speleothems that face the walls of various niches and passages. One can assume that this restricted visual access, for whatever reason also applied to ancient communities as well. The artistic endeavour comprised an array of imagery that included geometric forms, projected markings (spit spreads), finger dots and occasional cervids and caprids. One such area worthy of comment was a large speleothem section which had a series of motifs, undistinguishable marks and recognisable animals (Figures 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36). The majority of this imagery was on curtain surfaces that faced inwards, away from public view. On one side of the calcite curtain display was a space where the painted areas could be viewed, and beyond this, a large rock outcrop. Incorporated into this outcrop were two bowl-like deeply-gouged cupmarks, each of which would have once contained a small fire (based on residue analysis), thus illuminating the art, either as a commissioned piece of work or as a finished composition (Figure 37). Either way, the ambiance of the flickering light, plus the art and narratives it held would have created a powerful visual and audible performance for the communities using this section of the cave. The flickering effect would have made the imagery move and become animated.

Cueva de la Pileta (Benaoján)

We now turn to our final visit, the so-called "Lascaux of the South," Cueva de la Pileta (meaning Cave of the Pool). This privately owned cave system offers visitors an enchanting exploration of a remarkable natural phenomenon, which, by chance, houses some of the most exquisite and idiosyncratic paintings I have ever encountered. The tour was guided by the current owner, Tomás Bullón, whose grandfather, José Bullón, made the initial discovery of the cave in 1905 while searching for bat guano (a valuable nitrogen- and potassium-based fertilizer). This discovery occurred three years after the European scientific community began to accept the notion that figurative engravings and paintings might be the product of early prehistoric human activity— i.e., the Early Modern Humans (EMH) of the Upper Palaeolithic era. A pivotal figure in this shift was the French Catholic priest-turned-prehistorian Abbé Henri Breuil, who visited the cave in 1905 after reading a report by Spanish enthusiast Colonel Verner. Verner had been introduced to the cave via a bat-filled chasm and initially speculated that the paintings and engravings were created by the Moors, an Arab-Berber group who settled in Spain and Portugal during the 8th century. As Verner explored the cave, he also discovered human remains and various ‘markings’ on the walls. It is now understood that these human remains were from a later prehistoric period, and the ‘markings’ were much older.

Figures 38 to 46 (below). A selection of painted images (with their D-Stretch counterparts) from Levels 1 & 2.

When Abbé Breuil visited the cave in 1905, he immediately recognized several artistic characteristics indicative of an Upper Palaeolithic origin, particularly the styles of horse and caprid paintings. Of particular interest were the depictions of fish, as well as extinct species such as felines and gazelles. Scientific dating of these paintings has presented challenges, primarily due to the pigments, which may consist of inorganic compounds. Our exploration of the cave system, spanning multiple levels, revealed little evidence of flowstone formations covering the paintings. The cave was accessed via a series of steps which lead to an entrance which was later cut and is not the original entrance entered by Tomás’s grandfather. Currently, a thorough study of the cave’s rock art is currently being conducted by a team from the University of Seville.

As mentioned earlier, Tomás Bullón himself guided us through the cave system, granting us unprecedented access to three levels of the cave. We were not disappointed. The second level, which is accessed by a ladder, is adorned with intricate visual narratives that include both figurative and non-figurative imagery. Notably, the pigments used in this section vary in shades of red, black, and a rare yellow, suggesting different artists and chronologies (Figures 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 & 46). The experience of entering this part of the cave was overwhelming, and while I cannot encapsulate those few hours in a short paragraph, I can echo Howard Carter's famous words: ‘We saw wonderful things.’

I would now like to briefly discuss a set of peculiar figures discovered by Tomás Bullón’s father and grandfather—what were referred to as ‘turtle’ motifs by Breuil and Obermaier. These images were initially termed ‘turtles’ because no similar depictions existed elsewhere in Palaeolithic Europe (Figure 40,). While archaeologists know that Mediterranean turtles existed during the Upper Palaeolithic, one would expect such creatures to appear in cave art near the coast. Closer inspection of these enigmatic motifs suggests they may provide insights into the economy of southern Upper Palaeolithic Europe, potentially rewriting our understanding of it. This concept was first recognised by Gimenez Reyna (1965, 36-39).

Traditionally, it was believed that advanced Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherer societies followed complex strategies, such as seasonal food gathering and selective hunting of game, to support their communities. However, the so-called turtle motifs seem to depict animal corralling, likely involving cervids and caprids. The sub-circular line forming the corral or enclosure is outlined by a series of short vertical lines, painted in red. These lines probably represent wooden posts or staves (similar to corrals used by pastoralists and herders, for example, the maasi mara in Kenya or reindeer herders of the Sami of Lapland) (Figures 47, 48, 49). Extending outward from the circular corral are, in several cases, between one and four double-lined channels or, what I term ‘funnels’ (Figure 50 & Figure 51), which can be interpreted as funnels designed to guide animals into the corral. Inside the corral-like motifs, irregularly placed short lines represent hoof mark pairs. One of the corral paintings even includes a caprid figure painted with yellow pigment—this figure is not visible to the naked eye but is revealed using the D-Stretch algorithm (Figure 52 & Figure 53).

What does this tell us about early prehistoric society and economy? As previously noted, these motifs are unique to this region and period. Based on the style and pigments used, they clearly belong to the Upper Palaeolithic, likely dating between 18,000 and 28,000 years ago. What we once considered standard hunting, fishing, and gathering practices—based on opportunistic hunts and seasonal resource collection—now seems far more complex. To provide context, I reference the rock art in northern Europe, particularly Norway and the Isle of Man, where, despite being from a Mesolithic context, we observe early forms of domestication or control of wild fauna. In anthropological terms, this can be compared to the way the Sámi people of Lapland corral reindeer. In the depths of Cueva de la Pileta, it appears that prehistoric communities were employing similar techniques, challenging our previous assumptions about their hunting and economic strategies.

FIGURE 47 to 53

A selection of herding corrals within the Level 2 area, clearly showing timber-posted enclosures with connected funnelled entrances. These features probably represent a different economic aspect to Upper Palaeolithic Europe. The herding corral with the yellow painted cervid (centre) is on a stepped slope leading to Level 3

A selection of herding corrals within the Level 2 area, clearly showing timber-posted enclosures with connected funnelled entrances. These features probably represent a different economic aspect to Upper Palaeolithic Europe. The herding corral with the yellow painted cervid (centre) is on a stepped slope leading to Level 3

© George Nash

FIGURE 47 to 53

A selection of herding corrals within the Level 2 area, clearly showing timber-posted enclosures with connected funnelled entrances. These features probably represent a different economic aspect to Upper Palaeolithic Europe. The herding corral with the yellow painted cervid (centre) is on a stepped slope leading to Level 3

A selection of herding corrals within the Level 2 area, clearly showing timber-posted enclosures with connected funnelled entrances. These features probably represent a different economic aspect to Upper Palaeolithic Europe. The herding corral with the yellow painted cervid (centre) is on a stepped slope leading to Level 3

© George Nash

A quick note on what is the future for rock art research

When I was an undergraduate student over forty years ago, I could not have imagined that, by 2025, archaeologists and anthropologists would be incorporating physics and chemistry to reconstruct historical narratives. Today, these scientific disciplines play a significant role in the majority of fieldwork, research, and publication within these fields. As I have noted previously, we—the scientific community engaged in rock art and cave research—are on the verge of a remarkable revolution in this area of archaeology. What I find particularly fascinating is how science can greatly enhance our understanding of the social norms and ritual behaviours of past societies. To be fair, when I was a research student, my work primarily relied on basic statistics (thanks to Christopher Tilley), so perhaps the seeds of this revolution were already beginning to take root, albeit in a more traditional, pen-and-paper form. Clearly, the next major advancement will be the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Currently, there are a number of extensive research projects being undertaken within the Iberian Peninsula (and elsewhere around the World) that uses such methods. Indeed, the First Art team (based in China, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Wales) have been involved in a number of cave projects throughout the Iberian Peninsula. The rationale of the team is to apply hard science to better understand the processes of creating [and conserving] rock art. The fundamental questions raised in our search for some of the answers includes identifying pigment recipes. Note the vast majority of applied pigments are of varying hues of red, black and, occasionally yellow. In order to provide strength to pigments, Palaeolithic artists would have applied organic binders, such as egg yolk, saliva, urine and water in order to create a durable paste. Different recipes were used in different places and at different times, over, say a 50,000-year period. In some cases, more than one colour has been used to construct, say, a figurative image (e.g., the sleeping bison in Altamira Cave). This hard science approach can be added to, say, a philosophical discourse. For example, I have applied this approach using chaîne opératoire (a chain of operations) method; from extracting the haematite from its source to creating the desired pigment consistency and then applying it to a panel, and then to create a work of art. Each stage of pigment production could be entwined with ritual behaviour. All modes of production, from haematite extraction to the finished composition, can account for at least 13-14 stages (see Nash 2018, 169-71).

In many instances, Palaeolithic artists utilised the natural topography of cave walls to enhance and accentuate specific features of representational animals, such as the rear quarters, head, neck, or entire torso. This technique is particularly evident on the walls of Cueva de la Pileta. In Cueva de la El Tesoro, artists subtly integrated the shape and width of natural cracks in the rock to outline the body lines of a caprid. Specific studies conducted on French and Spanish caves have shed light on this process, revealing how artists deliberately selected panels and employed the topographical features to create images with a three-dimensional effect, as seen in sites, such as Chauvet Cave in the Ardèche.

Contemporary research in European caves often focus on assigning dates to prehistoric imagery, a task that has been fundamental since the resolution of the Altamira controversy in 1902, when it was first proposed that cave paintings could be dated to the Palaeolithic period. In the early years of research, the dating process primarily relied on two types of evidence: the style of the figurative representations and their association with artifacts, as well as, when possible, stratigraphic deposition. However, the accuracy of these early dating methods was often speculative. Despite this, many early 20th-century researchers were surprisingly accurate in their assumptions, particularly regarding the identification of specific animal species—such as bison, elk, horse, mammoth, red deer, and reindeer imagery —based on their artistic style (each figure-type observing certain artistic rules of a generic theme) and their extinction date range. During this period, and continuing to the present day, archaeologists also used environmental evidence to establish broad chronological frameworks.

With the advent of chronometric dating techniques, such as C14, AMS, and Uranium-Thorium dating, scientists are now able to narrow the dating of specific figurative images to within a few centuries of their creation. However, precise dating is contingent upon the correct environmental conditions and methodological procedures. Fortunately, many limestone caves in the Iberian Peninsula contain calcite flowstone (or stal), which can be found either beneath or above the painted or engraved imagery. In some rare cases, calcite flowstone is present both below and above the artwork, enabling scientists to establish both a maximum and minimum date range. To ensure the reliability of these dates, researchers typically split calcite samples, which are then processed and dated at multiple laboratories. As a result of these advancements, research teams, such as the First Art team, have successfully extended the dating of figurative and non-figurative imagery in Maltravieso Cave (Cáceres, Spain) to approximately 65,000 years ago, likely created by our nearest cousins, Neanderthals (Figures 54, 55 & 56) (Standish et al. 2025).

What did we get out from our expedition?

Our expedition was a remarkable journey into the heart of Palaeolithic rock art in southern Spain. We focused on exploring some of the region’s most significant caves, including Cueva del Tesoro, Cueva de la Victoria, Cueva del Nerja, and Cueva de la Pileta. Each of these sites presented unique opportunities to examine Palaeolithic rock paintings and engravings, some of which are considered masterpieces of early human expression (Figure 57). As we ventured deeper into each of the caves, we not only encountered striking artwork but also discovered hidden spaces and niches that revealed much about the sacred lives and practices of our distant ancestors, using artistic endeavour as a ritual device.

One of the most captivating aspects of our expedition was the diversity of art forms we observed. In Cueva del Tesoro, for example, we found intricate engravings and paintings that depicted a wide range of abstract symbols and occasional figurative art. These early artists used natural cave features to enhance their works, incorporating the cave’s contours and niches into their compositions. The careful placement of these images within hidden corners and less accessible spaces suggested that these areas may have held special significance for the people who created them, possibly serving as sacred or ritualistic sites. The deliberate selection of these spaces challenges our understanding of the art, encouraging us to think about the symbolic roles these artworks might have played, and who they might have played to.

Visiting Cueva de la Victoria also deepened our insight into the social and cultural practices of the Palaeolithic and later, Neolithic mortuary practices. The cave contains distinct paintings from both periods, many of which are found in secluded niches or behind narrow passages, further suggesting their ceremonial or spiritual importance. The artwork here, like in Cueva del Tesoro, often blends with the natural features of the cave, indicating that the environment itself may have been seen as part of the artistic and spiritual expression. The intricate images, in particular, displayed a sophisticated level of skill, suggesting that Early Modern Humans were capable of more complex cognitive processes than we might have initially assumed.

Cueva del Nerja and Cueva de la Pileta provided even more fascinating discoveries. The engravings and paintings in these caves, found in hidden alcoves and on calcite curtains (speleothems), continued to highlight the deep connection between Early Modern Humans and their environments. The placement of images in such remote areas of the caves seemed to reinforce the idea that these were not merely decorative expressions but were deeply integrated into the daily lives, rituals, and beliefs of the people.

One thing worth mentioning which is largely a global rule, no clear landscape representation is ever present in Upper Palaeolithic cave art (no hills, mountains or rivers). However, what I could see were images, such as the multiple hoof marks, animals and corrals at Cueva de la Pileta, in particular, which would have occupied physical spaces within the landscape. Are we therefore witnessing motifs and figures that substitute landscape? Another long story perhaps?

Our expedition, therefore, not only allowed us to appreciate the artistry of these ancient paintings and engravings but also illuminated the thought processes and cultural contexts behind their creation, enriching our understanding of the cognitive and spiritual lives of our Palaeolithic ancestors.

The cave team for the Bradshaw Foundation expedition included myself, Peter Robinson, Kate Robinson, Lucy de Laszlo, Damon de Laszlo and Sam de Laszlo. We humbly thank all those people involved who gave us their invaluable time to provide an unforgettable experience.

Note: All images in this article do not have scale owing to the fragility of the panel surface.

Selected Reading

Bullón Giménez, J., 2006. Cueva de la Pileta: monumento nacional desde 1924: acontecimientos históricos más importantes sobre La Pileta y la familia Bullón (1905-2005).

Cantalejo, P. & del Mar Espejo, M., 2014. Málaga: en el origen del arte Prehistórico Europeo: Guía del Arte Rupestre. Ediciones Pinsapar.

Cantalejo, P., Maura, R., Aranda, A. & del Mar Espejo, M., 2007. Prehistoria ce las cuevas del Cantal. Editorial La Serranía.

Clottes, J. & Lewis-Williams, D., 1998. The Shamans of Prehistory. New York: Abrams.

Collado Giraldo, H., 2018. Handpas. Manod del Pasado.

David, B., 2017. Cave Art. London: Thames & Hudson.

David, B. & McNiven, I.J., (eds.) 2017. The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garcês. S., Capilla Nicolás, J.E., Collado Giraldo, H., García Arranz, J.J., Garrido Fernández, E., Gomes, H., Nash, G.H., Nicoli, M., Oosterbeek, L., Pérez Romero, S., Pepi, S., Rosina, P. & Vaccaro, C., 2022. Las manifestaciones gráficas rupestres en el dolmen de Soto (Trigueros, Huelva). Junta de Andalucía. Consejería de Cultura.Oxford: Archaeopress.

Garcês, S. & Nash, G.H. (eds), 2024. The Prehistoric Rock Art of Portugal: symbolising animals and things. London: Routledge.

Gimenez, S.R., 1965. La Cueva de la Pileta, Monumento Nacional. Translated by G.W.B. Huntingford. Malaga.

Gimenez, S.R., 1958. The Cave of Nerja [Malaga, Spain]. Translated by G.W.B. Huntingford. Malaga.

Hodder, I., 1982. The Present Past. London: Batsford.

Hodder, I., 1990. The Domestication of Europe. London: Blackwell Press.

Lawson, A.J., 2012. Painted Caves: Palaeolithic Rock Art in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leroi-Gourhan, A., 1968. The Art of Prehistoric Man in Western Europe. London: Thames & Hudson.

Lévi-Strauss, C., 1963. Structural Anthropology. London: Nicholson.

Lévi-Strauss, C., 1964. Mythologiques. Paris: Plon.

Lévi-Strauss, C., 1973. From Honey to Ashes: Introduction to a Science of Mythology. Volume 2. London: Jonathan Cape.

Lévi-Strauss, C., 1986. The Raw and the Cooked, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. & Dowson, T.A., 1988. The Signs of all Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic Art, Current Anthropology 29, 2. 210-17.

López del Hierro, A., 2016. The Cave at Nerja. Editorial Palacios y Museos.

Macerlean, F., 2012. First Neanderthal paintings discovered in Spain. New Scientist (https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn21458-first-neanderthal-cave-paintings-discovered-in-spain/).

Munn, N., 1973. Walbirian Iconography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nash, G.H., 2003. Northern Hunter/Fisher/Gatherer European Rock-Art and Spanish Levantine Rock Paintings: A Study in Performance, Cosmology and Belief. Norges Teknisk-Naturvitenskapelige Universitet (NTNU). Trondheim: Norway.

Nash, G.H., 2018. Serra da Capivara (north-east Brazil) and the Limarí Basin (Chile): A tale of two rock art landscapes. In A. Troncoso, F. Armstrong & G.H. Nash (eds.) Archaeologies of Rock Art: South American Perspectives. London: Routledge, pp. 150-176.

Nash, G.H., 2022. A Reappraisal of the Cronk yn How Stone, Isle of Man. In A. Mazel and G.H. Nash (eds.) Signalling and Performance: Ancient Rock Art in Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 191-211.

Rosal Padial, Y., Fernández Rodríguez, L-E. and Liñán Baena, C., 2019. Guide de le Grotte de Nerja. Palacious y Museos.

Standish, C.D., Pettitt, P., Collado, H., Aguilar, J.C., Milton, J.A., García-Diez, M., Hoffmann, D.L., Zilhão, J. & Pike, A.W.G., 2025. The age of hand stencils in Maltravieso cave (Extremadura, Spain) established by U-Th dating, and its implications for the early development of art. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 61. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352409X24005194 Tilley, C., 1991. Material Culture as Text: the Art of Ambiguity. London: Routledge.

Cantalejo, P. & del Mar Espejo, M., 2014. Málaga: en el origen del arte Prehistórico Europeo: Guía del Arte Rupestre. Ediciones Pinsapar.

Cantalejo, P., Maura, R., Aranda, A. & del Mar Espejo, M., 2007. Prehistoria ce las cuevas del Cantal. Editorial La Serranía.

Clottes, J. & Lewis-Williams, D., 1998. The Shamans of Prehistory. New York: Abrams.

Collado Giraldo, H., 2018. Handpas. Manod del Pasado.

David, B., 2017. Cave Art. London: Thames & Hudson.

David, B. & McNiven, I.J., (eds.) 2017. The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garcês. S., Capilla Nicolás, J.E., Collado Giraldo, H., García Arranz, J.J., Garrido Fernández, E., Gomes, H., Nash, G.H., Nicoli, M., Oosterbeek, L., Pérez Romero, S., Pepi, S., Rosina, P. & Vaccaro, C., 2022. Las manifestaciones gráficas rupestres en el dolmen de Soto (Trigueros, Huelva). Junta de Andalucía. Consejería de Cultura.Oxford: Archaeopress.

Garcês, S. & Nash, G.H. (eds), 2024. The Prehistoric Rock Art of Portugal: symbolising animals and things. London: Routledge.

Gimenez, S.R., 1965. La Cueva de la Pileta, Monumento Nacional. Translated by G.W.B. Huntingford. Malaga.

Gimenez, S.R., 1958. The Cave of Nerja [Malaga, Spain]. Translated by G.W.B. Huntingford. Malaga.

Hodder, I., 1982. The Present Past. London: Batsford.

Hodder, I., 1990. The Domestication of Europe. London: Blackwell Press.

Lawson, A.J., 2012. Painted Caves: Palaeolithic Rock Art in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leroi-Gourhan, A., 1968. The Art of Prehistoric Man in Western Europe. London: Thames & Hudson.

Lévi-Strauss, C., 1963. Structural Anthropology. London: Nicholson.

Lévi-Strauss, C., 1964. Mythologiques. Paris: Plon.

Lévi-Strauss, C., 1973. From Honey to Ashes: Introduction to a Science of Mythology. Volume 2. London: Jonathan Cape.

Lévi-Strauss, C., 1986. The Raw and the Cooked, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. & Dowson, T.A., 1988. The Signs of all Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic Art, Current Anthropology 29, 2. 210-17.

López del Hierro, A., 2016. The Cave at Nerja. Editorial Palacios y Museos.

Macerlean, F., 2012. First Neanderthal paintings discovered in Spain. New Scientist (https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn21458-first-neanderthal-cave-paintings-discovered-in-spain/).

Munn, N., 1973. Walbirian Iconography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nash, G.H., 2003. Northern Hunter/Fisher/Gatherer European Rock-Art and Spanish Levantine Rock Paintings: A Study in Performance, Cosmology and Belief. Norges Teknisk-Naturvitenskapelige Universitet (NTNU). Trondheim: Norway.

Nash, G.H., 2018. Serra da Capivara (north-east Brazil) and the Limarí Basin (Chile): A tale of two rock art landscapes. In A. Troncoso, F. Armstrong & G.H. Nash (eds.) Archaeologies of Rock Art: South American Perspectives. London: Routledge, pp. 150-176.

Nash, G.H., 2022. A Reappraisal of the Cronk yn How Stone, Isle of Man. In A. Mazel and G.H. Nash (eds.) Signalling and Performance: Ancient Rock Art in Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 191-211.

Rosal Padial, Y., Fernández Rodríguez, L-E. and Liñán Baena, C., 2019. Guide de le Grotte de Nerja. Palacious y Museos.

Standish, C.D., Pettitt, P., Collado, H., Aguilar, J.C., Milton, J.A., García-Diez, M., Hoffmann, D.L., Zilhão, J. & Pike, A.W.G., 2025. The age of hand stencils in Maltravieso cave (Extremadura, Spain) established by U-Th dating, and its implications for the early development of art. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 61. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352409X24005194 Tilley, C., 1991. Material Culture as Text: the Art of Ambiguity. London: Routledge.

Rock Art Links