This is an account written and translated by the eminent prehistorian Professor Chen Zhao Fu, Chairman of the Rock Art Research Association of China (RARAC) at the Central Institute for Nationalities in Beijing, presented here as part of the Bradshaw Foundation - China Rock Art Archive.

Following the footsteps of the famous Chinese geographer Li Daoyuan, author of the scholarly tome 'Shui Jing Zhu' written over 1,500 years ago, Professor Chen Zhao Fu rediscovers the rock art sites of China; 'In Search of a Vanishing Civilization' is a short account of his monumental quest, traveling over 20,000 kilometers and through 10 provinces, to bring the prehistoric rock art of China to the attention of the world.

Rock art painted or incised by early human of the Paleolithic Period is the earliest record of mankind's daily life.

Rock art was first discovered in northern Europe in the 17th century, and then so many have been found since not only elsewhere in Europe but also in Asia, Africa, America and Australia. It seems that early man throughout the world used rock surfaces as his first "canvas". Apart from in a handful of ancient civilizations, written history goes back only a few centuries, but tens of thousands of years earlier than the first written word, these images afford us to glimpse into our ancestors' past. UNESCO suggested in 1981 that a world catalogue of rock art be compiled, but in international studies of the subject, China is still a blank in 1984.

Having traveled many places all his life, Li Daoyuan's records derived mostly from personal knowledge with his own eyes. In the year of 494, he went with the King to Inner Mongolia and many other places, his book has over twenty points of recorded rock art sites, including the regions cover half of the area of China.

The book describes the techniques of the rock art as painting and engraving, and the subject matters are all embracing, reflecting the matters of major importance in human life, such as wild animals, domestic animals, masks, symbols, footprints and especially various animal hoof prints were recorded in a large number. Of course, these rock art works were not made in the same times, they are from several ages, reflecting the features of societies before the fifth century, and also these works surely were made before 1,500 years ago.

Concerning the description of rock art in the book, Li Daoyuan offered valuable contribution; we can find a good deal of information from his book. They’re also some records confirmed by recent investigations.

There is a story, in 1975; an archaeologist working in Inner Mongolia became extremely interested in an account of the book. It said that there were painted cliffs in Yinshan Mountains included many horse-like figures. The archaeologist decided to investigate and in following year the rock art was discovered in Langshan district, western Yinshan Mountains. Since then, great efforts have been made and more than thousands engravings have been discovered. They have been named the "Yinshan Rock Art".

Many rock art recorded in classical literatures have not been discovered. The famous book "Shui Jing Zhu" recorded that at Mount Yellow Cow on the bank of Changjiang (Yangtze) river in Hubei province, there figures representing a herdsman leading a cow; but nobody can see them now. Most probably they vanished long ago.

On the other hand, many rock art exist which are not recorded in any ancient literature. For instance, in Cangyuan county of Yunnan province, a popular legend says that there are many figures on the cliffs that appear from time to time and have been regarded as magic figures. By following this legend, the archaeologists finally discovered the Cangyuan rock paintings.

Modern investigations began with Prof. Huang Zhongqin's description of those at Hua'an in Fujian province in 1915, and with the Swede F. Bergman's survey of Kuluke Mountain in Xinjian (Chinese Turkstan) in the late twenties. But it was only in the fifties that discoveries began to be made in large numbers, starting with area around Zuojiang River Valley in Guangxi; then at Cangyuan in Yunnan in the sixties and in the Inner Mongolian Yinshan Mountains in the seventies. Besides these remarkable finds, rock art was known to exist in at least 100 counties Spread over 18 provinces and regions.

My investigations took me 20,000 kilometers through 10 provinces. The rigorous of the journey - the rock art sites are mostly in rugged country inaccessible to cars - were amply rewarded when a clamber up a cliff or a trudge through shoals and rapids brought me face to face with scenes of hunting, flock-tending, sacrificial rites, dances and battles as our progenitors practiced them in the remotest antiquity, as if the curtain of time had been swept from before my eyes.

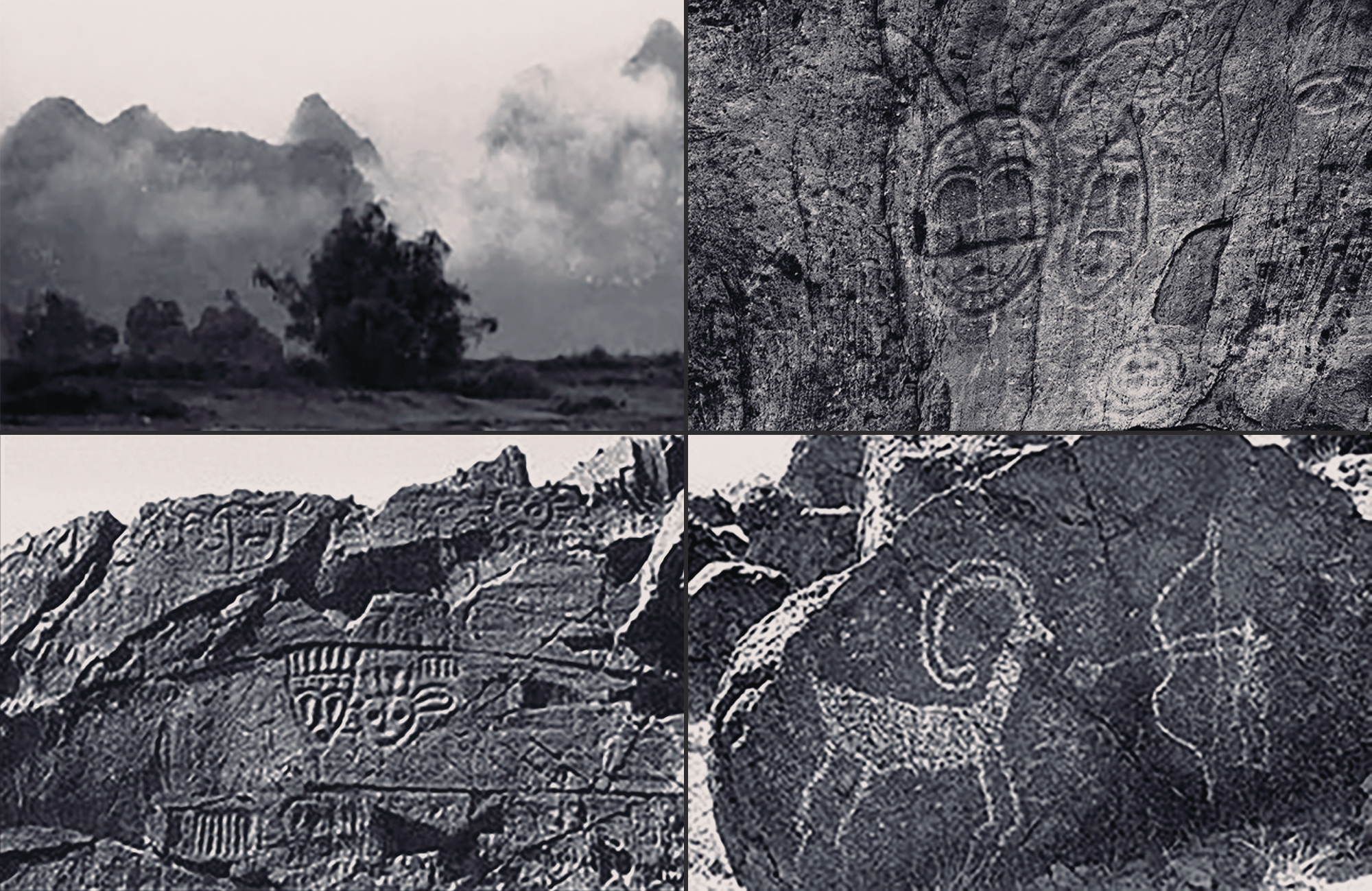

I first made my way to the grassland of Inner Mongolia. The range of the Yinshan Mountains runs across the central and southern parts of the Inner Mongolia. It is over 1,000km long from west to east and over 50km wide from north to south, with an elevation of over 1.000 to 2,300m above sea level. The northern slope of the Yinshan Mountain Range is gentle and gradually passes into the plateau below it, but its southern slope is steep and abrupt, separating itself sharply from the plain below it and forming a natural barrier between north and south. The Langshan Mountains in the western section of the range. My investigation of rock art is limited to the region of the Langshan Mountains.

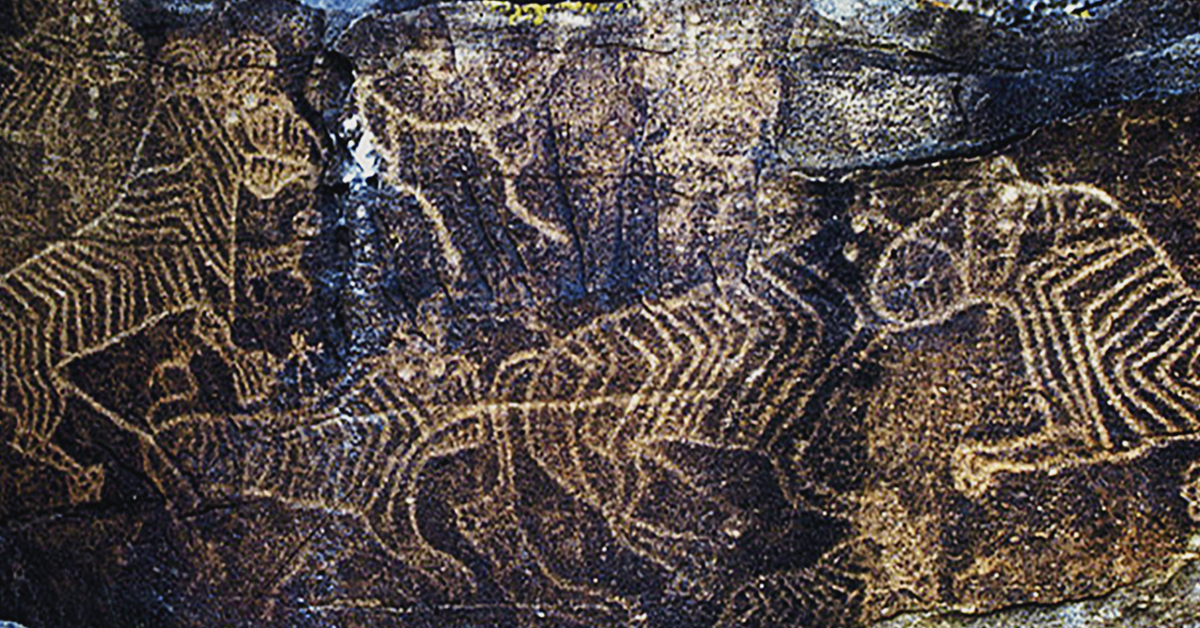

In Langshan region, over 10,000 cliff carvings were discovered. All these carvings are chiseled, grated and engraved on cliffs or bare huge rocks and they are still quite clear after thousands of years of weathering by wind and rain.

The Yinshan rock art were done over a long period, the earliest being tentatively dated to ten thousand years before the present Pictures show ostriches and megaloceros, these species long extinct in this part of the world.

I visited Dabakou and Tanyaokou in the Langshan. At Tanyaokou, at the foot of the magnificent green mountains, to the east and west of which spread the red mountains, are jutting stones like tier upon tier of dilapidated red ramparts, and beneath them are 10 rock art sites. I was particularly impressed by a well preserved, life-size representation of a camel with two tall humps and a small tail etched in individual lines, its head held high, staring superciliously ahead and its strength indicated by the small animal under its foot.

The simplest engraving of Yinshan consists only of a flying arrow, heading for a fawn. They symbolized the action of hunting a flock of sheep is on their way to pasture, being herded by a dog - a picture full of life.

More complicated engraving described scene of warfare between nomadic tribes. They attack one another with bows and arrows, and the defeated warriors who survived are seen fleeing in panic -- looking downcast. The conquerors are depicted full of strength and grandeur with headdresses of long cock's feathers. These scenes are of great historic value since these ancient wars actually took place.

The Yinshan rock art mirror the economic activities of the ancient there at various angles. The early ones reflect mainly a hunting economy, depicting single-man hunting, double-man hunting, and group hunting and encircling hunting scenes. The major weapons are bows and arrows, along with clubs, ropes and knives. In the carvings of a later period, the number of domestic animals increased. In addition, there are scenes of herding and changing pasture grounds, along with pens and stables. During hunting, people usually disguised themselves, trying their best To assume the forms of beasts so as to decoy them.

The rock art also described the social life of the Yinshan people. Praying was one of their commonest customs. The witches and wizards (shamans) formed a great group and all-important actions in life preceded with praying ceremonies. The practice of human sacrifice was very prevalent then. There are scenes of dancing during which also exhibited some immolated human beings, whose heads or headless corpses sometimes being discarded aside. As regards clothes and ornaments, we can also find their fashions in the rock art. People are commonly depicted as naked in the early carvings, and it is only in the ones of a later period that a small number of them are clad in robes tied with a belt in the waist. Their hair is either braided or shaved and they wear deer horns or bird feathers as headdresses and occasionally nose ornaments. Tail ornaments were the fashion of the time. People wore them in hunting, praying or dancing.

The carvings show that the ancient people of Yinshan mainly worshipped animals, and also celestial bodies and gods. The various gods are shown in the great number of anthropomorphic masks. The worship of these things was a concrete reflection of the primitive religious beliefs of the ancient Yinshan people.

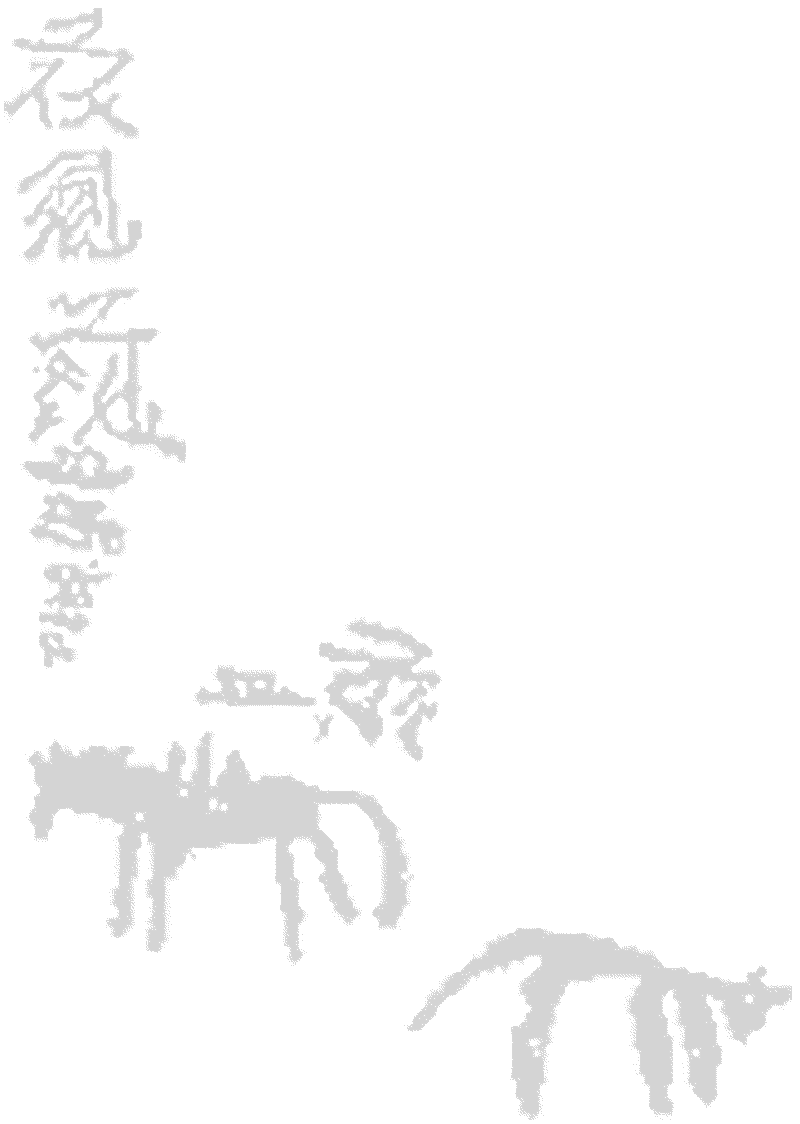

The subjects of the drawings are rich and varied. Some of them show the various kinds of birds and animals. Among them we can know that the Wulanchabu rock art was made after the beginning of the age of husbandry, since a large number of them are depictions of domesticated animals and the pasturing of them, newly born and young animals and the caressing, herding and feeding of them as well as the suckling of the young by the mother animals. These drawings show the transition from the hunting to the husbandry age, reflecting the change in the life of the people who turned to raising animals that they got by hunting formerly and how they loved their domesticated animals, and how much they wished that the animals would breed and multiply.

I made my way to Xialekou northeast of Bailing Monastery in Wulanchabu, where the grasslands extend to the horizon under a blue sky and undulating ridges wind through the wilderness topped by rocks, some standing, some lying. Many of these bear images of animals like fantastic paper cuts, some executed realistically, but mostly doubled up, overlapping, sketchily indicated or deformed, most imaginatively conceived. Mixed in with these are scenes of hunting, cattle tending and dancing, and hoof prints similar to those discovered in Mongolia and Siberia. Scholars have suggested that these are related to the cult of motherhood and female sexuality.

This artistic style shows that the idea of beauty had also changed. In the age of hunting, hugeness, great strength and great fecundity were considered beauties, and so the physical impressiveness of animals was emphasized in the period, but upon entering the age of husbandry, following the improvement of the material life of man, his idea of animals was also changed, and he was no longer satisfied with external form only. To a certain extent, his interest turned to inward intellectual loftiness. Simplicity, extraordinariness band together patternization was considered beauties. The purpose behind the drawing of animals changed gradually from worship to enjoyment and practical usefulness. It is very obvious that symbolized figures are convenient for recording social and production activities. The later Chinese pictographic characters were developed from the symbolized rock art.

Less well known to the general public than the Yinshan rock art is those of the Helanshan Mountains, that rises above the Yellow River where it flows into Inner Mongolia.

The Helanshan Mountains, which lie in center and north of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region like a great ridge sticking out, are famous mountains on the plateau of northwest China. On the cliffs of this chain of towering hills covered with dense forest, our ancestors left an everlasting rock art. Numerous petroglyphs are inlaid, like the stars shining in the sky, on the cliff surfaces of a dozen mountains passes. When making an inspection tour along the foot of the mountains and enjoying these petroglyphs, one can feel as if he were walking along a gallery of ancient carvings.

The northern Helanshan Mountains contain a concentration of mask engravings. A shepherd who disturbed the sand covering the lower slopes discovered the first, a fair number of carved slopes have now been excavated, looking from a distance like blue pools on the hillside. They are large, flat and smooth, and the masks are carved on them in serried lines. Probably many more remain buried beneath the sand.

All the masks are grotesquely distorted, some with an outsize nose, some with ears as big as the face itself, others covered in hair like an ape. Their expressions vary from rage to smiles, and patterns on them indicate either tattooing or the use of masks. The headgear is just as bizarre. One has a branch above it decorated with grass-like and ray-like headdresses - we wondered if perhaps they were meant to be feathers or a sacred halo - while others wear a conical hat and makeup that may be hunting camouflage. The weird images and the fertile imagination of the artists are quite out of the common run, and one is led to presume that the largest pieces served as idols for the worship of celestial and telluric deities. Perhaps the masks of Apollo, the celestial bodies, the totems and other symbols display the beauty of the patterns and forms, leaving the drawings full of mystery.

The masks are also found in the ravines that stretch back into the mountains, where hunting scenes also occur. One group of over 50 animals in Xifu Ditch differs from the masks in its accurate and graphic representation, showing how closely early man observed the beloved and inexhaustible source of his subsistence. Wild oxen, camels and bigheaded sheep are delineated in only a few strokes. Carved on a hilltop towering forty meters over Huihui Ditch is a life-sized ox outlined with three parallel lines, inside which are cut three kids, creating an effect of movement.

Some pictures are distinct and deep; other have peeled off and become blurred, for the workmanship of these grand petroglyphs spanned more than thousands years, yet the manifold means of artistic expression can still be obviously seen by its lines, shallow or deep carvings, thin or thick outlines, and with a dotted style, all of which show our ancestors' craftsmanship and aesthetic judgment.

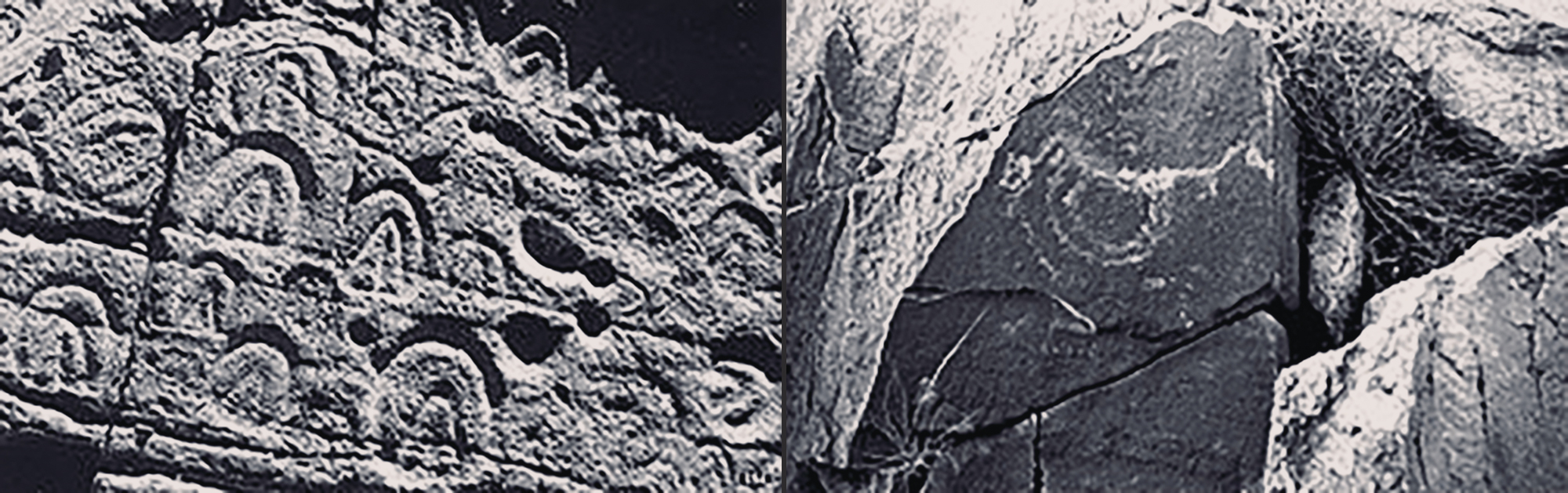

Probably the most intriguing concentrations of rock art will be found in Xinjiang.

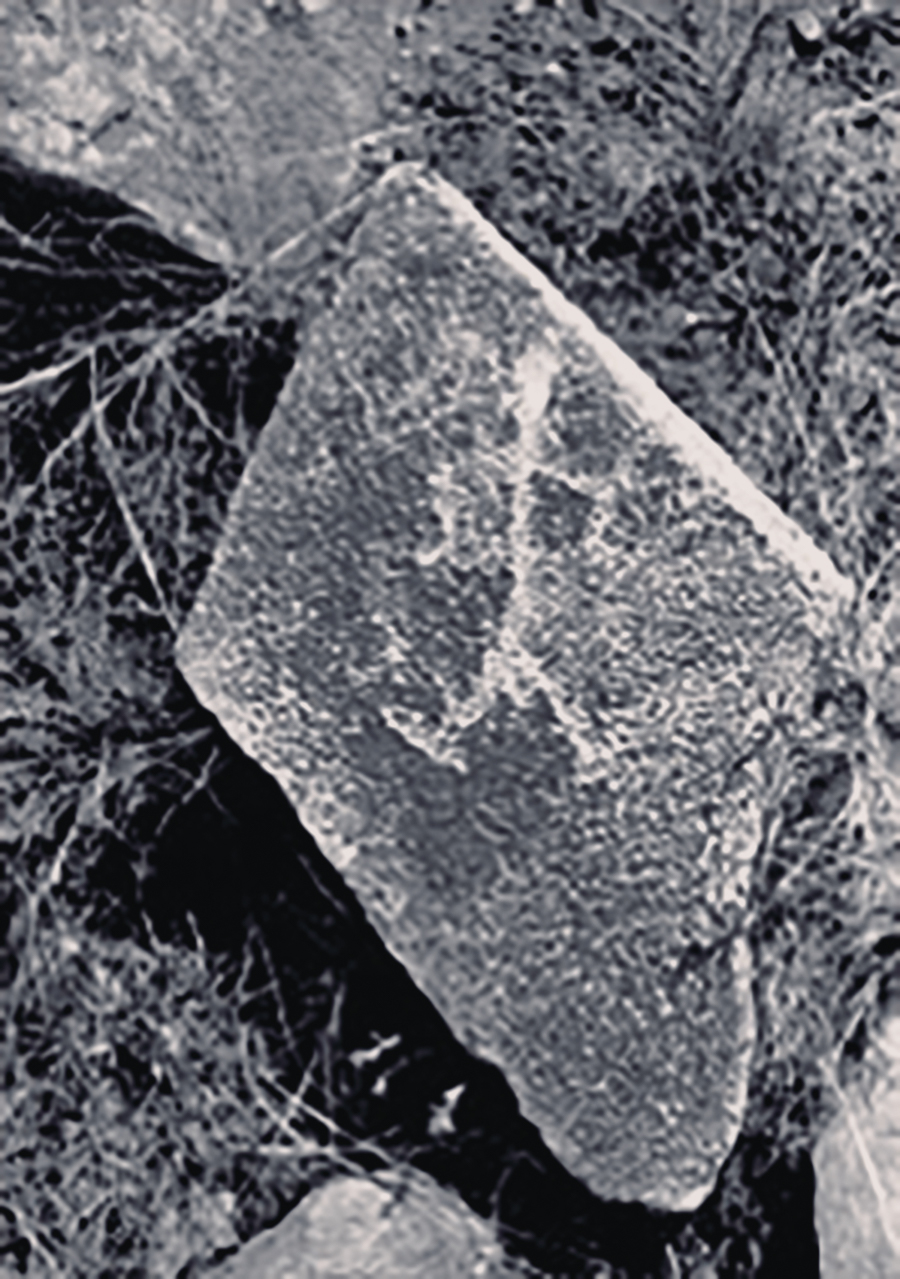

The central Xinjiang's mountain known as Kuluktag was investigated by F. Bergman in 1928 and written up in his "Archaeological Study of Xinjiang". In 1985, I drove from Lopnur through the Gobi for a day to the village of Xindi. We started early, the moon like an arched line, and look thinner like a brow. In the background of dark blue sky, innumerable stars vie with each other in radiating myriads of rays. It is just the plateau there have such beautiful starlit sky. Our lorry (truck) sped on along a narrow region between Kuluktag Mountains in the north and Tarim Desert in the south, by Kongqi (peacock) River. In the beginning, we saw thriving t. But gradually we entered extremely hot desert and finally our lorry sunk into the sand, and put in a tight spot. After five hours affect our lorry run again. In the late at night we arrived Xindi. This village was marked in the Map of the People's Republic of China, but its whole inhabitants just three persons now. In the noise and excitement barks they all came out to welcome us. In the next dawn from Xindi to south, three miles south of there on the left bank of the tortuous Xindi River, we came upon clusters of rock engravings at the base of a hundred-meter limestone cliff that towered over a flat stretch of ground overgrown with elms, willows and blossoming wild pomegranates where the river skirts the mountain in a broad curve.

Kuluktag engravings extend fifty meters in either direction, but the most important section is in the middle. In one picture here a running cameleer waves his hands above his head to rouse one of his charges from its lethargy. In another, a mounted herdsman pursues three or four horses and a flock of goats, while the sun sheds its rays over the dense foliage of two trees. This rare landscape is remarkably well balanced.

In northern Xinjiang, the largest rock art sites are in Altai Mountains, where there are evident links with those of the Eurasian steppes. The pictures of spiral-horned deer resemble those discovered in Mongolia.

In recent years, archaeologists have found much beautiful rock art around Altai Mountains. There are many engravings in the open air and two caves with rock paintings. These precious cultural relics are attracting worldwide attentions of scholars in history, archaeology, art and ethnology.

From many years of study, we found that so many unexplained matters in the historical studies could find their solutions in rock art, which also give us frequent revelation. They are especially helpful in our studying the life and people living on desert and prairie, who moved frequently from place to place, which resulted in the loss of material record of their history. Archaeological relics always leaves a serious limit in giving a all-side view of the human history; but the rock art can help supplement, in many ways, what is lacking. Therefore, they play an important role in the textual research of tribes, customs and religions.

Altai rock art represent a part of the chain that links the north prairie region of Europe, Asia and America. They are closely related to the neighbor districts, and at the same time, typical reflect the pre-historical life of the Altai District and the life there in the later history.

We can see Altai rock art have a rich content. The principal topic is that of the realistic life of the flock people, its environment - the trees, the grass, and the grazing land, and the animals such as elephant and kangaroo that are rarely seen in the north. Rock art such as shooting animals and herding livestock, acrobatic, dancing, worship activities, and communal marriages all vividly reflect the ancient economic and culture from different angles. The composition of the rock art has a good variety. Each is natural, vivid and full of life.

In the rock art of dancing and acrobats, they show the entertaining activities of the folks, besides as wolves chasing sheep or the wild animals on the prairie. Each engraving is so composed that one can see clearly the implied meaning: wolf and deer confronting each other in which the deer horn is exaggerated so that it stands, though physically weaker than the wolf, daring to fight against the enemy.

These valuable ancient arts, as a whole, show a crystallization of the wisdom and creativity of the ancient Altai people. They once again present, in front of us the ancient life of the local people. The rock art was created by a broad variety of ethnic groups, testifying to the diverse racial make-up and the different cultural background of the inhabitants, and reveals connections with USSR, Mongolia and the Near East. Xinjiang is the most complicated region in China as far as rock art is concerned, since the dates and artist nationalities are difficult to determine. The study of the Altai rock art is only a beginning. There are still further studies in front of us. Nevertheless, it is a good beginning, there will be still more achievement that will add a brilliant page in the course of archaeology.

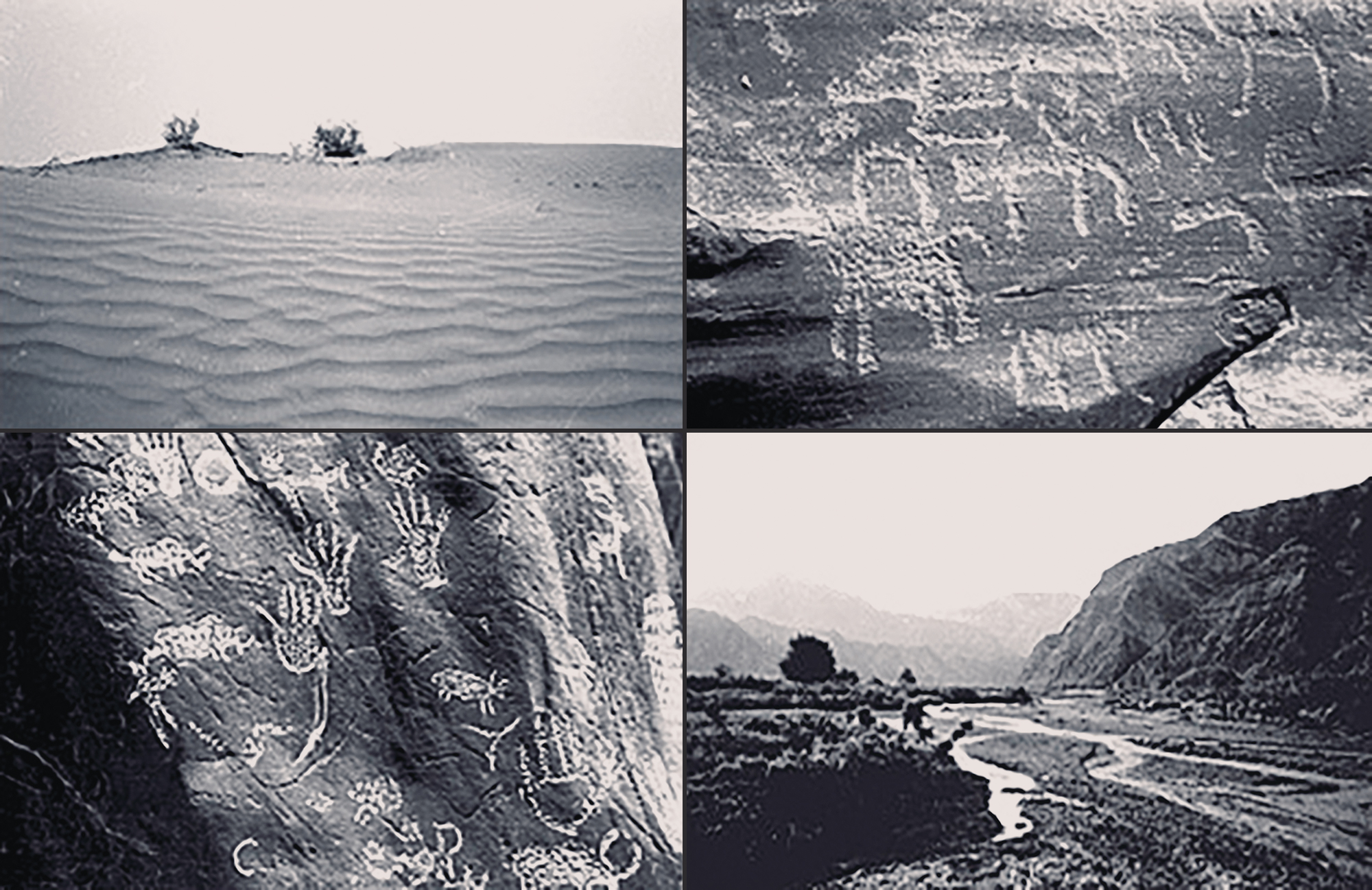

Quite different from the rock art of the north are the distinctive red-painted ones of south, most typically those of Yunnan and Guangxi. Ten sites have been found in Cangyuan in the Awa Mountains on the Burmese border. Cangyuan rock paintings were first discovered in January 1965.

With a subtropical climate, the fertile Awa region has plentiful rainfall and only 40 frost-free days years. It is suitable for the growth of dry rice, paddy, maize, millet, buckwheat, potatoes, cotton, hemp, tobacco and sugarcane, as well as bunch subtropical fruits as bananas, pineapple, mangoes, papayas and oranges.

The rock paintings can be seen only as one draws near. The pictures cover a space thirty meters wide on the cliff, and the top of the pictures is about five meters from the ground. All individual images are not big but concentrated. The rock paintings here, as elsewhere, have suffered from erosion by rain and magma. Except for those blurred by erosion, the images are still very clear and bright.

In the side of the cliff, many long narrow flags hung on the branch of trees. These are the villagers offered to the rock paintings. We get some scripture which printed by wood block from the creak of the cliff, when we open the scriptures there are all written with Tai Nationality minority's characters; below the paintings we also saw another offerings such as food and some money.

Site Six also can be seen very far away a huge yellow cliff inlay in the green, trees, bushes and grass covered the path of the mountain. After half an hour's drive we stopped at the foot of a mountain and began to climb. At first we followed a steep, zigzagging path, but later we had to hack our way through bushes. Thorns scratched our hands and legs. We soon grew tired under the blazing sun and were out of breath. When we were so tired we could no longer walk, an almost vertical cliff suddenly confronted us. When I come near, the rock paintings contents are very abounding, there are scenes of fighting, herding, hunting and performing acrobatics, meanwhile some persons wearing feather capes relates to religious significance. There are too many things for the eyes to take in.

Most of the Cangyuan rock paintings were painted on the smooth surfaces of the vertical cliffs in red color. Spectrum analysis suggests that the artists for their red pigment used hematite or similar ores.

Judging from ethnographical data, the binder for mixing the pigment was probably ox's blood. The Wa people - a major ethnic group in Cangyuan - still used this as binding medium in the paint for the ceremonial drawings on their headman's house in the 1950s.

While fingers seem to have been employed as a painting tool, some kind of brush was also used to create the larger drawings. About 1,000 drawings and symbols are scattered on the cliffs of the ten sites. The main motifs are: human figures, spirits and ghost, houses (pole-dwellings, huts on the tree), animals (buffalos, zebus, pigs, leopards, elephants monkeys and birds), and symbols which include one handprint.

One picture shows a circle of dancers holding one palm upward and the other at the side, much as local dancers do today. The figures are shown in vertical projection, lying on the ground like a five-petal led flower. The picture of the village is of great interest, it's extent being symbolized by a circle within which there are more than ten pole-dwellings (surprisingly resembling those depicted in the rock art of Valcamonica, Italy) Outside the circle there are several zigzag lines, perhaps representing the paths winding through the mountains. The paths are crowded with people driving sheep and pigs in all directions towards the village; some people are busily husking rice with a pestle and mortar, preparing for a sumptuous feast. Perhaps the villagers were about to hold a feast to celebrate successful fighting.

Based upon a synthetic study of these drawings and symbols, we reconstruct the daily life of the people who left these paintings on the cliffs. These people could build permanent house and led a sedentary life in large settlement. They engaged in herding and planting. They raised oxen and pigs, and pounded some kind of cereal (rice?) in the mortars. They also hunted with spearing, shooting and other methods lassos. Some form of leadership probably existed. Battles often occurred. Rituals and related dances were held very often. Most of the rock paintings were probably created during or after some important rituals.

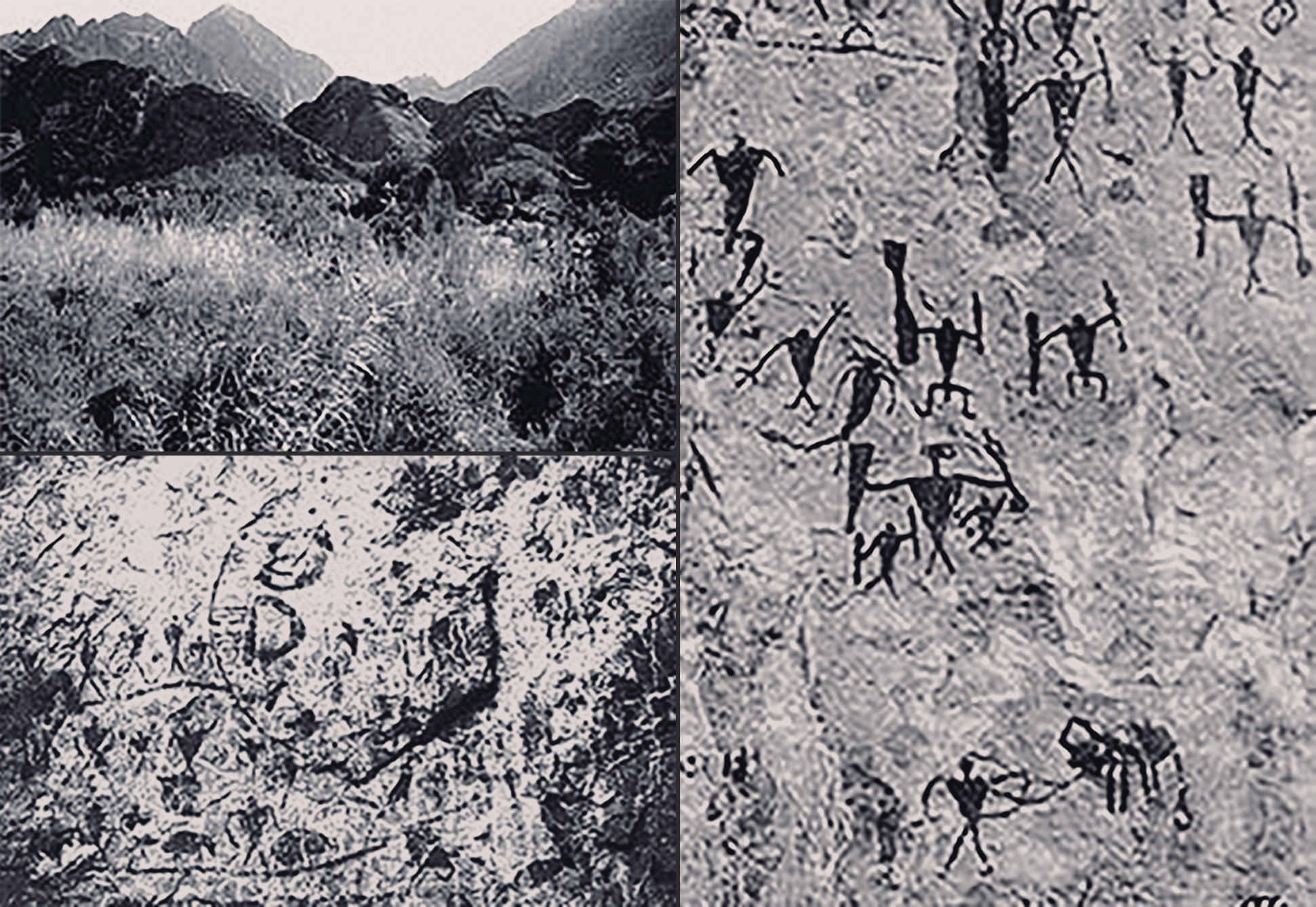

The Zuojiang River Valley is situated in the southwest of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. It shares a border with Vietnam, and flows from the southwest to the northeast about 345 km long. It runs through a mountainous area, and is famous for its picturesque landscape formed by the process of erosion of limestone. The work of Nature has given shape to numerous exotic pinnacles and spires, bizarre sinkholes and caverns, scenic hills and underground streams.

The main topography of the river region is clusters of peaks and isolated peaks. In the upper reaches of the river there are many clusters of peaks; while in the lower reaches there are many isolated peaks. They also served as the medium for depicting people's creative and imaginative expressions.

Along Zuojiang River there are eighty rock painting sites, but Huashan come out first. From side view it seems that the mountain was cut off a half. The river winds along the mountain ridge, in the front the Huashan shaped a huge awl (taper), the paintings beginning from half way up to the mountain, and until the foot of the mountain. The top of the cliff sticking out, just protect the pictures. The drop of water keep dripping from the top cliff reaches about 5m parts from the foot of the mountain. So we can say the paintings were painted in the shelter, but the shelter is very immense stretch several hundred meters wide. In the oppositive bank, there is a wide expanse of flat land: in this land turn one's head back to see Huashan, the mountain become more magnificent, people facing Huashan to took place ritual meeting here is very suitable. We stayed in Huashan a long time, enjoying ourselves so much as don't want to return. When the land is enveloped in a curtain of darkness, we put up for the night in the boat. It is the dead of night, the river is very dark, sometimes there are dog barks in the distance, but few and far between.

The legends spread from ancient times, but the formal scientific investigation did not occur until 1950. From 23 Sept to 1 Oct 1950, Guangxi Ethnic Minority Society and History Fact-finding Mission investigated the rock paintings. Up to now the investigations have made for several times. Some articles and reports about these investigations have been published, then the rock art of Zuojiang River become one of the most famous rock art sites in China.

Up to now, 80 rock art sites have been discovered in the Zuojiang River valley. Eighty percent of the sites are on the cliffs of both sides of the River and its tributaries, most places of the sides are located on the curves of the river and a few sites are a bit far from the rivers.

In the rock art of Zuojiang River, there are different kinds of images, such as human figures, dogs, birds and implements: knives, swords, bells and bronze drums. Besides, there are images of boats and sexual intercourse. However, the praying figures are the main motif. The most of the figures have big bodies; the biggest figure is 3 meters tall.

The typical combination of the images is that in the center is a tall praying figure with a knife or a sword by his waist. Under his feet there is a dog, beside him or between his legs there is a bronze drum with a bright star. On both sides of the figure there are lines of smaller figures in profile that seem to dance for joy. The larger character is often depicted as a positive figure (frontal). The body is bigger and the posture remains consistent; the arms raised and legs apart. But the shapes are not all the same; some have round heads with broad chests and smaller waists. In some the head and neck are one rectangle, and the torso is triangular in shape. The figures are unclothed except for endless variations on headdress. The figures shown in profile with the same posture are always smaller than positive ones, and the headdresses are less frequent. There are many more of these smaller, profile figures, crowded together around the frontal praying figure.

In Zuojiang, the rock painting of Huashan is the biggest, most magnificent and most typical. The name "Huashan" literally means the "mountain of the pictures". On the cliff, the picture is 210 meters in width and 40 meters in height. There are many images, especially at the lower part of the cliff, 1,819 images can be still seen include over 1,500 praying figures. The largest figure is 3 meters in height and the smallest is only 30cm tall. They are distributed over thousands of square meters yet very concentrated.

Scholars suggest that all praying figures in Zuojiang are dancers. The posture, with arms rose upward and legs squat, is the frog dance posture, as the frog is the totem of this tribal group. There are frontal and profile figures, but the postures are the same. Often in totemic religious, the people will dress up to resemble the totemic animal: that is the reason.

According to popular legend, the images on the cliff are those of frog-gods. Frogs are highly thought of in the culture of the local Zhuang people. They are called "Maling" in the Zuang language. The local people have an ancient Maling Festival every year. During this time, they worship the frog-gods and imitate the frog's movements in dance. They believe frogs are daughters of the Thunder-god, sent to be messengers between heaven and earth. The Thunder-god commands the wind and rain. Worshipping the frog gods is important to the Zhuang people who believe the gods will help bring them good weather for an abundant harvest and a healthily, flourishing population. So the paintings on the Huashan cliff are not just records of human activities, but also images of their gods. Through this artwork, scholars can explore the ancient people's mysterious ideas of deities and their illusory ideological world.

Art was more than a thing of beauty. It was also a method of compelling the forces of Nature to work for people. In a mysterious and dangerous world making new picture seemed to promise the artist that he and his people would not be injure. It may be true. Certainly the artists who risked their lives scaling the treacherous cliffs had other than purely aesthetic ends in view, and the locations themselves suggest an appeal to collective spirit of the tribes to get rid of the disasters of flood and drought, guarantee a flourishing population, and bless and protect the warriors.

Since the 1950s, discussions on the dates of the rock art have been carried out in academic circles. We have concluded that these rock paintings cover a time frame from the Warring States Period to the Eastern Han Dynasty (475B.C.- 220A.D.). The C-14 analysis has briefly proved our determination.

During this period, the Zuojiang River valley was still in the last stage of the primitive society and early stage of the class society. The rock art has the age characteristics, a strong color of primitive religion, with an atmosphere of immense zeal and vigorous mystery. The rock art of Zuojiang River valley is not only the gem of China, but also a spectacular artistic flower in the treasure house of the world.

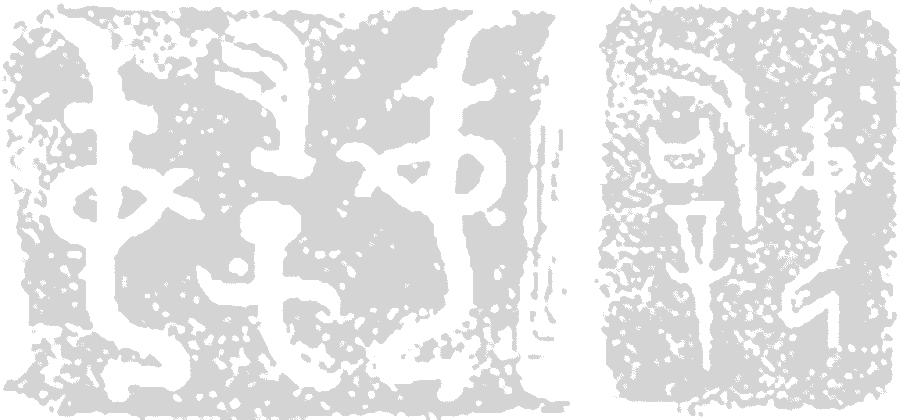

Many masks rock engravings have been found in Southeast area. In 1979, a rock engraving site was discovered in Jiangjinyan, southwest of Lianyungang City 9km, close to the sea. The size of this site 22 * 15 meters and the elevation is about 20 meters. This is a huge shiny black rock, slope with three obvious groups containing masks, crops, animals, birds, the sun, star, and varying symbols.

The Lianyungang rock engravings are of great interest, most of the figures show mythical beings represented as anthropomorphic faces on the end of stalks; the crop designs appearing in the rock engravings reflect just one of human life in this southeast coast region of the Stone Age. Perhaps they reflect the worship of the sun and the earth, as agriculture was the main resource of the people. Scholars consider that they belong to the Neolithic age, Ca 5,000 years ago.

There are five rock art sites have been discovered in the southeast coast area. Such as Lianyungang, Jiangsu; Hua'an, fujian; Wanshan, Taiwan; Zhuhai, Guangdong and the ancient rock carvings in Hong Kong.

About the Hua'an rock art, we have an ancient literature of Tang dynasty (618-907 A.D.) said: there is a mountain, at its foot is a very deep pool dwelling an evil crocodile that always did harm to the villagers and they had to move to other places. One night it thundered hard. The mountain was shaken so hard and felling into the pool. The evil crocodile was stoned to death. The pool water, with the crocodile's blood, flowed over the fields. At the same time an inscription appeared on the cliff.

Around 1915, Prof. hua first discovered Hua'an rock art. Seventy years passed, in 1985, I went to Hua'an and found the pool (Taixi) become very different now, the water comes rarely and when it does, the flow is rapid creating many shoals. As a result it is very difficult to navigate, but in two banks the mountains and rivers are emerald green.

Here, Taixi makes a winding, forming a deep pond, about 10 meters across. The southern bank is a sheer cliff, about 30 meters high containing six separate groups of engravings.

Hua'an rock engravings are highly stylized or abstract. There enigmatic quality has tempted many people in to guessing at their meaning. Scholars considered the engravings like some ancient writing of minority ethnic group.

After my investigation In the May of 1985, I considered the subject matters of Hua'an rock engravings are dancers, masks and animals. The masks may be related to the dancers, in some primitive dances, the participants wear masks, legs squat, arms raise, naked and under the buttocks a tail dress. Breasts always mark the females. The atmosphere of this dance is rough and enthusiastic. It is not surprising that the images of the figures are similar to the strokes of Chinese ancient writings; Chinese traditional painting emphasizes likeness in spirit rather than form. Perhaps this is the main difference between Chinese and Western ancient rock art.

Rock art contains the most ancient testimony of human economic and social activities, ideas, beliefs and practices. Rock art also contains the most testimony of human imaginative and artistic creativity, long before the invention of writing, and constitutes one of the most relevant aspects of the common cultural heritage of humanity. Some general characters seem to be common to all rock art areas in China.

The lack of sophistication in composition reflects the simplicity of man's infant imagination, but no matter what their technical limitations, the pictures, whether carved or colored, achieve a realistic and vigorous vitality that later artists must struggle to recapture but which appeals to us directly over the centuries.

The artists were skilled at representing images of animals. The engravings of Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang include a great number of very life-like representations of sheep and goats. The artists of southern China were familiar with monkeys and buffaloes. One of the Cangyuan rock paintings shows monkeys climbing the mountain hanging their tails downward while those going down hill have their tails upward. This shows that the artists were well acquainted with monkeys. Even though the figures are flat, great expressiveness was achieved by full use of the silhouettes. In this case, emotions, including violent feelings, are expressed. These methods are simple but also clever.

The characteristic of this art is a combination of sharp observation and rough style. The rough, freehand figures are very true to life, an effect that later artists have often failed to reproduce, despite many attempts.

Thus we accept for that the rock art artist has a situation similar to that of art and artists at all times. The Greek artist created his masterpieces for the decoration of temples; the Romanesque and Gothic artists did the same things for their churches. As Altamira, the cave in Spain, has been called the "Sistine Chapel" of Quaternary art. So, this indicates that "art for art's sake" is rarely true in rock art.

Besides, China's rock art have special meaning itself, that they led the birth of Chinese pictographs writing.

Rock art, a historical record by hunters of the Paleolithic Age unto tribesmen of modern times, documented human actives over the long years. Their rich contents reveals the social practices, philosophies, religions, psychology and aesthetic tendencies of the early man.

Originally, before the invention of writing, man used many methods to help memory, to express ideals and to exchange opinions. Among these methods, to keep records by pictures were the most important one. When man drew images to record something and to express certain wishes, then rock art was appeared. Rock art is one of the ways used to keep records by pictures in prehistoric times.

Keeping record by picture exert a tremendous influence for the invention of writing, as picture writing appeared. Then, the picture writing evolved into pictograph. The trace of this evolution is very clear in Chinese writing.

In Yinshan, Inner Mongolia, we find an inscription beside some engravings that says, "The Parents of Writing". In Helanshan, we find another inscription beside some engravings, "The Writing Deity's Writing (the writing of a writing deity).

These inscriptions reflect the relation of rock art and writing, especially Chinese writing, because it is pictographic character. They are connected not only because they both record daily life, drew man's preserved form in self-expression and creativity, but also that Chinese pictographic characters are connected with rock art directly.

The pictorial element of Jiaguwen is also clear and very close to the rock art. In this case, the Chinese ancient writing in the earliest period very closed to the picture, to the rock art, sometimes all the same between rock art and the writing, such as the sun, moon, mountain, bow, cart, field.... and so on. Then, we can say that the Chinese writing origin from rock art; or rock art exert a tremendous influence for the invention of the writing -- and the rock art really is the parents of writing.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ China Rock Art Archive

→ The Rock Art of Huashan, China - UNESCO World Heritage Site

→ Rock Art of China's Helan Mountains

→ Yinchuan World Rock Art Museum

→ Itinerant Creeds

→ Rock Art of Inner Mongolia & Ningxia

→ The Tiger in Chinese Rock Art

→ Life in Rock Art by Chen Zhao Fu

→ In Search of a Vanishing Civilization

→ The Rock Art of Wushan

→ Ancient Rock Carvings from Dazu

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network