English Afrikaans Arabic Ateso Azeri Chinese Dutch Ejagham Euskera Finnish French Fulani Galician German Hausa Hewbrew Hungarian Isizulu Italian Japanese Ju Hoansi Korean Kunwinjku Malay Maori Nama Nde Nigerian Pidgin Norwegian Portuguese Sepedi Spanish Swahili Swedish Thai Turkish Uzbek Welsh Xhosa

This statement is the product of deliberation among the Rock Art Network membership, and reflects our own vision of the values of rock art. We hope that the message will be shared widely. It is with this in mind that we have begun translating the vision statement into many languages.

The Rock Art Network recognizes the differences between various cultural interpretations of rock art. The vision statement is not set in stone, but rather it is intended to stimulate reflection and discussion. We encourage anyone who reads this vision statement and has comments to contact the Rock Art Network through the Editor, Bradshaw Foundation. What is important is the message of universality and significance of rock art and its dissemination. We welcome thoughts about enhancing the statement to make it more meaningful in your community.

Rock art is part of our global heritage extending back over 50,000 years. We can go almost anywhere in the world and find rock art. An artistic and archaeological legacy set in a landscape that may be a deep cave, overhang, cliff face or rock in the open-air, rock art poses questions about what it is to be human today. Before more of this fragile heritage is lost to unregulated development, mining, looting, defacement, climate change and other factors we need to find ways to make the public aware of its values and universality. Characterized by its creation on rock surfaces, rock art affords perspectives into the lives and beliefs of our ancestors and peoples often far removed from us in time. The painted, engraved and carved images, often of surpassing beauty, yield insights about how the makers felt about and perceived their world and the rituals they practiced. Where rock art is still being made today, in only a few places in the world, the same insights apply.

Rock art is a manifestation of the human impulse to communicate. While we marvel at the art of the master painters of the renaissance, and stand in awe before the pyramids, we must acknowledge too the genius of the artists of Lascaux and the other Ice Age sites in Europe, the beauty of San painted antelope in rock overhangs of southern Africa, the astonishing scale of the Nazca lines of Peru, and the so-called X-ray paintings of Australia’s Northern Territory - everywhere, from the Arctic Circle to the most southerly tip of the Americas, rock art is to be found. Rock art’s relevance reverberates even today as a living portal to the past. We cannot fully understand it without the explicit account of the makers, but it speaks to us powerfully. Rock art is in jeopardy - it is literally and figuratively ‘on the rocks’.

Since the late 1980’s the Getty Conservation Institute has undertaken training courses and projects in rock art conservation and management, including a one-year diploma course in Australia and short courses in California, as well as a field project in Baja California Sur.

The Rock Art Network* subsequently emerged after a series of workshops held in South Africa from 2005 to 2011 as part of the Southern African Rock Art Project. This program was extended to Australia between 2012 and 2014 as an exchange between rock art specialists, managers, and custodian communities from southern Africa and Australia. It culminated in a forum in Kakadu National Park in 2014 and a document ‘Rock Art: A cultural treasure at risk – How we can protect the valuable and vulnerable heritage of rock art’ in which four pillars of rock art conservation policy and practice were identified. This document served as the basis for the agenda of the 2017 Namibia colloquium ‘Art on the Rocks - A Global Heritage’ in which the main focus was on Pillar I - Public and political awareness - and Pillar IV - Community involvement and benefits. In 2018 a colloquium held in California and Texas continued this work: ‘Art on the Rocks - Developing action plans for public and professional networking.’

Among the institutions and professionals affiliated with the Rock Art Network, the Bradshaw Foundation was identified as a key partner. Operating since 1992, the Bradshaw Foundation’s database of rock art information, visual resources and its robust social media presence make it an ideal partner to host the Rock Art Network’s online hub.

The purpose of the Rock Art Network is to foster principles of research and of conservation, create network of collaboration and, importantly, promote public and political awareness of this fragile and irreplaceable global heritage.

* A list of persons and affiliated institutions appears on the Bradshaw Foundation site.

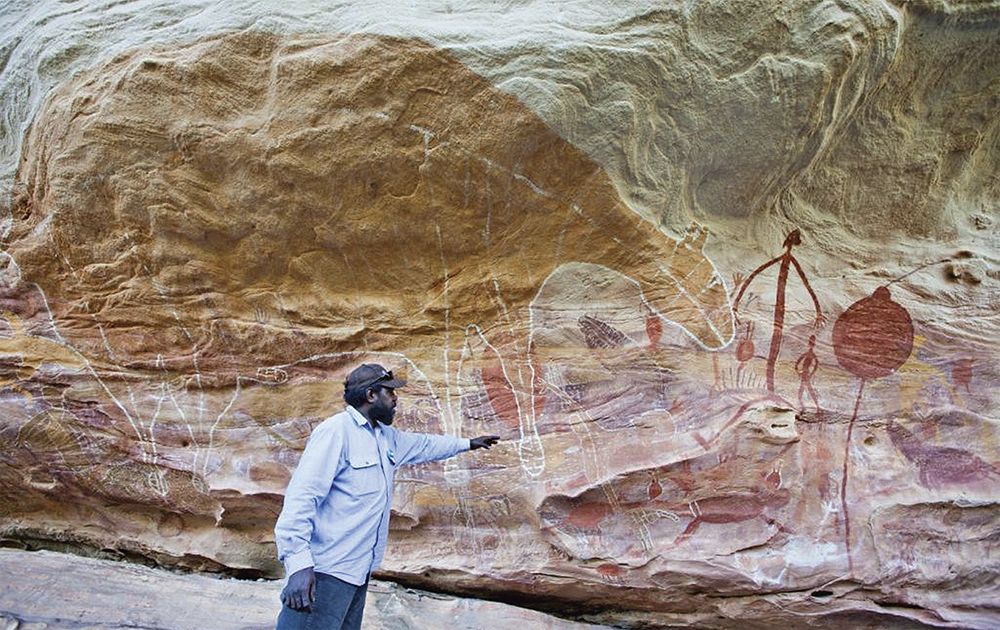

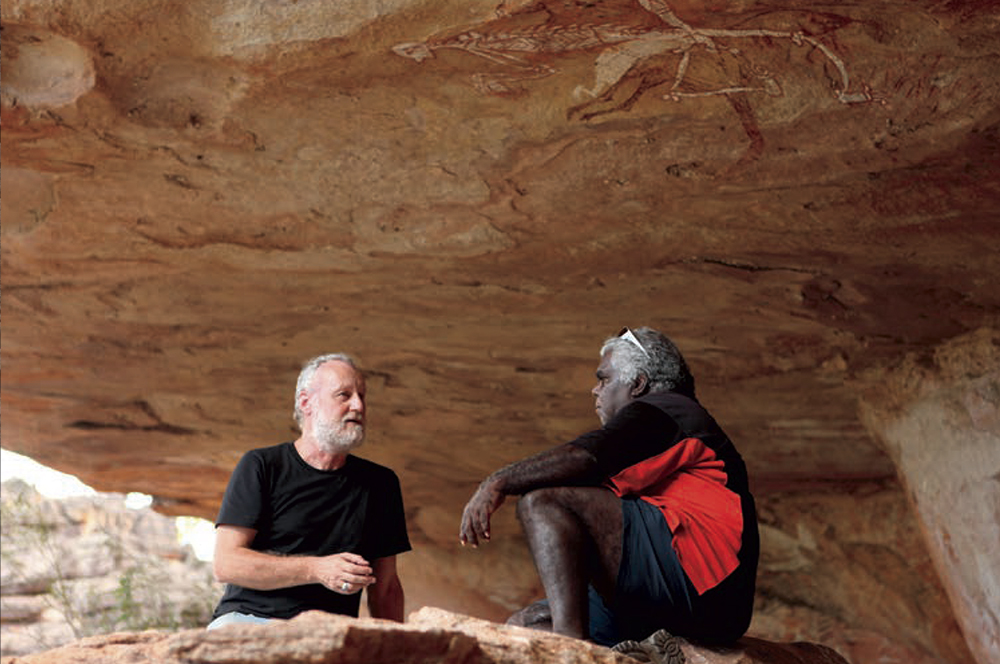

Stories on rock (above): Rock art has been created to tell stories over the course of the development of modern human species. We may not always be able to retell the stories from the creators of the rock art in the past, but the cultural insights we can still gain from this visual legacy are tremendous.

A unique record of spiritual traditions (above): Southern African rock paintings made by ancestors of the San (Bushmen) illustrate different ways in which power is received from the spirit world for healing, rain-making and controlling game animals. We interpret this art with the aid of San ethnography. In this example, the gures that are interpreted as healers wearing cloaks, face their patients and lay hands on them to draw out the arrows of sickness. Above their heads are bows, quivers containing arrows, and tasselled bags containing medicinal plants. The red lines coming from the face of the healer on the far left represent nasal blood that was believed to give the healer additional healing power.

Making sure these galleries have curators (above): Valuable works of art are protected in museums and galleries around the world and have highly trained people to care for them. The stunning legacy of rock art deserves greater attention to its curation and the training of people who understand options for rock art management and protection. Indigenous people, local communities, rock art researchers and conservation professionals need to work closely together to share knowledge.

A treasure of humanity (above): The beautiful almost life-sized giraffe petroglyphs in Niger were only documented in 1997. They are believed to be between five thousand and nine thousand years old. Despite its remote location the petroglyphs are under threat from mining and are being damaged by visitors including fragments being stolen.

Power from the past (above): The rock paintings found in the Drakensberg in South Africa and Lesotho are detailed, exquisite renderings testament to the great technical skill of the painters. The images embody many of the beliefs of the San people, including, as in this image, the spiritual transformation of ritual specialists or !gi:ten. The man has an animal head and cloven hoofs instead of feet, similar to those of the dead antelope in front of him. He carries a stick that is used during the trance dance, as well as ‘ y whisks’ made from the tail of an animal such as a hyena or wildebeest that were believed to ward off negative power. While this image is remarkably well preserved, many are suffering from ongoing deterioration.

Changing behavior through awareness (above): Rock engravings on private farms in southern Africa have been permanently damaged over the past century or more by visitors. The scratches over the human gures on this rock were already there when the rock was photographed in the first decade of the twentieth century. With increased awareness of the value of the rock art, this type of destruction has been supplanted by names and dates. Fortunately, most of the recent graffiti is confined to boulders without ancient rock engravings, but vigilance is needed to reduce the impact of this type of vandalism.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation