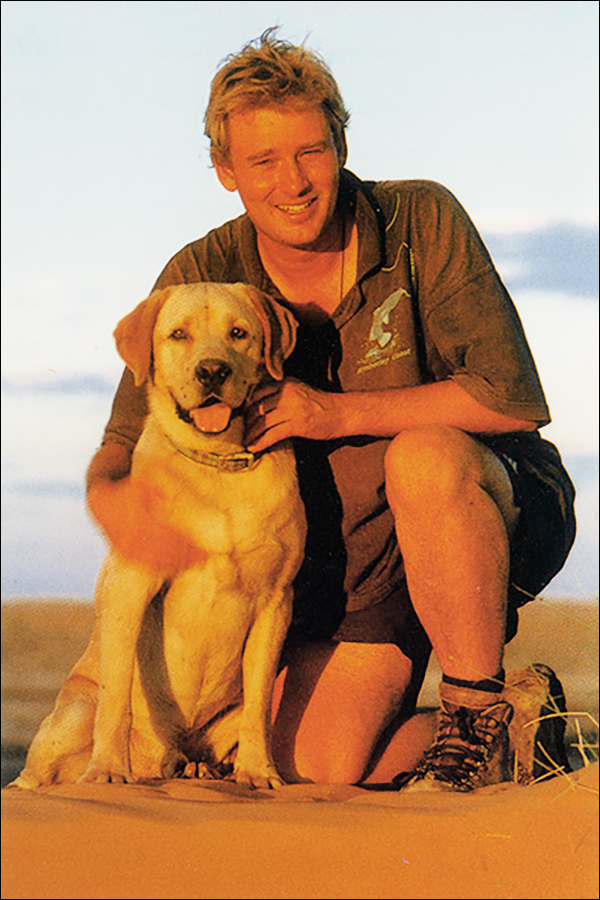

Hugh Brown a documentary photographer based in Australia. He has made it his life's work to document aspects of our world that are rapidly changing. People, towns, occupations and landscapes. It is his goal to take important photographs: not "pretty photographs". He describes his wish that "When I hang up my camera I want to feel that I have made a meaningful contribution to the life and conscience of our planet". Since 1998 he has photographed and chronicled the Kimberley region of Australia. Throughout the course of his photographic career Hugh has worked in 30 countries and produced seven large format coffee table books, as well as having work exhibited internationally with major exhibitions in South Africa and China.

To find out more visit www.hughbrown.com

In July of 2000, I determined to proceed with a trip that I had been planning for quite some time into the rugged Charnley River region: some one hundred miles north east of Derby. The Charnley flows through some of Australia's most dramatic and spectacular country and cuts a deep gorge for the final 40 miles of its journey into the Walcott Inlet, near where the freshwater meets the salt.

Much of the area's rock art is quite spectacular. The Walcott, itself, is quite spectacular and is characterised by fantastic fishing, huge 30 foot tides, spectacular freshwater swamps around its perimeters, a forbidding escarpment on its northern side and the barrier of the King Leopold Ranges on its southern. The tides are amazing and make an enormous 'roaring' sound as they come in from the sea.

For the walk, I would be carrying 75 lbs. of gear: including a large bowe knife, a Magellan-sponsored GPS, an EPIRB (an emergency satellite beacon), a pocket-sized survival kit (in the event that I became disentangled from my gear), a hat, strong boots and gaiters. Kanch would be carrying his own specially-designed dog pack that would hold his food between the food drops.

In country such as this, and carrying the amount of gear that I was, small things become more challenging and each day further tested my mental reserves. The helicopter reconnaissance flight had shown my readings of the maps to be accurate and the first few days would be covered predominantly along sand, which in itself was brutal, and beside Melaleuca-lined pools. Camp one, which I still recall fondly, saw me record the following notes:

Sun's gone down. Dinner's cooking. The reflections in the water were absolutely magnificent. Stunning!. It's so peaceful and magic out here. Kanch and I are both pretty tired, but it's great having Kanch along because it takes your mind off your own pain. Kanch struggled a bit, but has done fantastically overall. I'm on the easy bit and the country is still brutal. Lugging 75 pounds of gear doesn't help. Saw heaps of animal tracks in the sand today. Marvellous! Dingoes, Wallabies, Freshwater crocodiles and heaps of bird tracks.

Days two and three revealed country that was much the same as the first. I was lucky to cover more country than I had scheduled. The fishing was amazing soon caught enough for a good meal. The power of this river in flood must provide for an awesome spectacle, and I was later to learn from conversations with people at the Broome office of the Department of Conservation and Land Management, that the flood had peaked at levels of up to sixty-five feet during this years wet.

The explorer, Frank Hann, in his travels of 1898 discovered the Charnley while looking for fresh pastoral country and named it after Walter Chearnley of Nullagine to record his gratitude to the latter for his assistance in supplying him with cattle on a number of occasions while in that area. He was later to write, it would require a man greedy of trouble who would want rougher country to travel over. This, I was to realise sooner than I would have liked!

The evening of day three revealed the most spectacular of sites. A 240-foot basalt cliff face that rose out of nowhere was sufficient to mask my exhaustion and cause me to grab for the camera as the sun made its daily dash for the horizon. The first photograph below shows the midday vista and the second the view prior to sunset. Sheets of sandstone were scattered with debris from the recent wet, and in the distance, the resident crocodile could be viewed as it lay on the surface of a deep round pool. The vista was incredible.

Wow. Sitting in the most awesome setting. Sheer cliffs, eighty metres high and the most unusual colour: black and yellow . I have never seen anything like them before.

Im going to have a day off tomorrow so that I can soak in this scene a bit more and give my blisters a rest. I've covered a greater distance today than I had hoped but it was hard going: mainly because of the gear that I am carrying. This spot that I am camping at is so beautiful: it is really hard to describe. The terrain today has been mainly sand and small river stones. Today’s five and a half miles has some serious blisters. It's hard to conceive that such beautiful spots as this exist and that I am one of only a very few white people that have ever visited here. I had some crows follow me for much of today, which was a bit disconcerting. I wasn't sure if they were waiting for me to keel over or were instead watching out for me.

Day five, to say the least, was tough. Well, I thought that today would be brutal and I wasn't wrong. I've just climbed down a 450-foot scree slope to get some water and the flies are quite unbearable. The scenery though is amazingly spectacular as the orange cliffs generated the most magnificent reflections in the most fantastic green water below. We got going at a tad after 0600 this morning and both Kanch and I look like we've come out of a war zone. Kanch is black and nursing a couple of blisters from his pack. I've got cuts and scratches from pushing through chest high spinifex and boulders. Twice, this morning, I badly rolled my ankle and was very lucky to be able to walk. Having said that, though, the scenery easily makes it worthwhile

This morning, I was faced with my first difficult choice for the trip. The first part of the gorge runs for about five miles and I knew, from the helicopter flight, that it was impassable without carrying flotation gear. On the South side there looked to be some very easy walking, but then no way to climb down to fresh water. I took the north side and wondered whether I had made a wise choice. It's still too early to tell, and I was getting worried until we found this scree slope, as we were both getting badly dehydrated. It's funny how life out here brings you back to the basic choices: choices that really do have life and death implications.

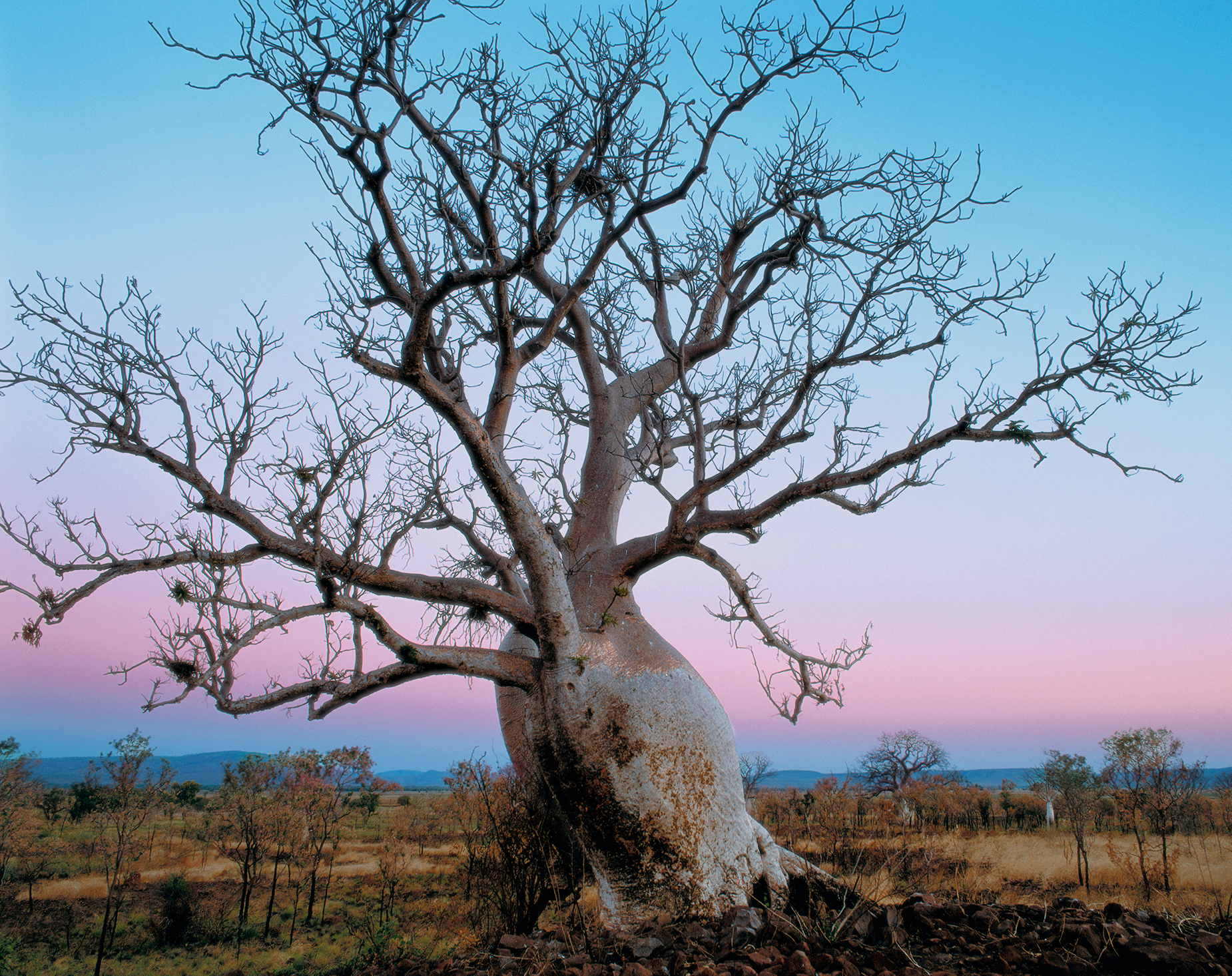

This morning has been hard also because I have had to carry Kanch's food. He was getting quite distressed, but now he's okay and it's me that has to lug all the gear. I can tell you, it hurts. The presence of the flies at the bottom of the gorge was distressing and ultimately forced our retreat to the rim. The views, and reflections, however will remain with me for a long time to come. The heat at the top of the gorge was also difficult and the shade afforded by a lone boab near the gorge rim, proved insufficient to enable the enjoyment of valuable sleep.

The isolation just hit home. A light plane flew high overhead. It hit home because you know there's nothing you can do to make contact. Itís just another noise in the wilderness. The first sign of man apart from the odd International jet tracers. I'm getting a bit nervous. The heat is oppressive today and there are clouds building up. We just have to negotiate three miles around the gorge rim. The challenge is not to panic and want to get to the destination too quickly. Better to wait until the sun drops low around 1600. Three hours to go. Quite dehydrated. Got three pints of water with me though.

It is difficult to describe the decision-making process in situations such as the above. The need to rest is tempered by a desire to reach water and the realisation that water will not be achievable for some unknown, but lengthy, distance to come. Decision-making in such cases can be anything but rational, regardless of how fortunate it may later prove.

Well, folks, we didn't panic, but my adrenalin got the better of me. We moved half a mile and now have a nice shady spot, which is much cooler. In 2 hours we will have as much water as we want. The challenge is to ration the water that we have until we reach that point. That will not be easy with the gear that I am carrying.

I dumped some gear just before: clothes, powdered milk and dog food. I figure that Kanch and I can share my food until we reach the next food drop and, if necessary, I can catch some fish. Hard work, but my spirits have risen and Kanch seems to be oíkay. I'm praying that he can hold out until we reach water. As the sun drops, we will really go for it. Took a nasty fall before in some Spinifex and took a fair bit of bark off my leg on a boulder. As I said, I expect this section to be the hardest of the trip because we cannot consume much water in the process.

Together with dehydration, the symptoms of exhaustion proved a major obstacle. Things that one would accomplish easily in daily life become major tasks and it was imperative to ensure the direction of full concentration to every step. The onset of nightfall saw our arrival at water in a tributary of the Charnley as the sandstone changed in colour from a washed out orange to a fiery red colour. Nearby, the following faded example of what appeared to be a Barramundi painting was present. Upstream, was the brutal gorge around which I had detoured.

To say that I'm a physical and aesthetic wreck would be a big understatement. I took two nasty falls on that portion, including one face plant into a small canyon. That's what severe exhaustion and dehydration do to you! Having said all that, Kanch was absolutely fantastic. He did incredibly well through what was very punishing terrain. We're both covered in spinifex sap, which is quite sticky, and Kanch, particularly, is black. Getting through that section today has given me some confidence, as I had been worried about it from the start. I'll be even happier when we get back onto the Charnley some time tomorrow. We're now about a mile up a tributary of the Charnley and it is quite beautiful. To get here meant a difficult climb down a scree slope to Pandanus Palms and a small stream.

By the end of day eight, I was two days ahead of schedule and sitting at the junction of Synnot Creek and the Charnley. The preceding two days had been relatively good walking, and I had enjoyed a camp at the base of a beautiful waterfall. Upon leaving the river and hiking to the top of a saddle to cut around a gorge that dropped straight into the river, my anxieties were heightened when, while walking down a dry creek bed, I nearly stepped on a snake. It is always difficult to tell the species of snake here in the Australian Kimberley as colorations vary markedly but the encounter had been too close for comfort: especially given that I was moving downhill and the pack weight kept pushing me forward. I had struggled to miss it, although Hann had enjoyed an even closer experience in this area in 1898: A new kind of snake went over my feet, killed him, a most deadly description of snake, had he bit me it would have been all up with me. I could not finish my map.

The commencement of day nine saw excellent progress: far better than I could ever have expected. Prior to the trip, I had anticipated that I would cover two miles per day in this area. However, by eleven am, I had already covered three miles and was thinking ahead to a week's fishing for Barramundi on the river's lower reaches, how I would manage Kanch in the presence of crocodiles and being able to view more rock art. Such thoughts would soon prove to be highly premature.

So much for the previous enthusiasm! I'm feeling a bit like a nervous wreck here at the minute. We've just taken two hours to cover a third of a mile. First, Kanch had an accident when he fell while I was trying to push him up a cliff. Stupid error of judgment on my part. We'd come to a dead-end so far as access along the river was concerned and we had to climb up and around. Me, being me, figured that we would be able to accomplish a cliff climb that was never really on. Anyway, Kanch froze and ended up on his back 36 feet below. Plus, I was very lucky that I didn't fall as well. I would have done much more damage than what Kanch did.

Then, a minute ago, we came too close for comfort to a fast-moving King Brown that was about two feet away. So, I'm just sitting currently to calm the nerves a bit. I can tell you that this is not an hospitable place: incredibly tough in fact. When things like this happen, the isolation really hits home. I just want to cover half a mile now so that we can make the next food drop. I'm not so sure I like this solo caper at the minute. Thank god for Kanch.

By six the following morning, I was sitting in the main gorge at the point of my second food drop waiting for help to arrive. My tripod was broken, my camera gear was stuck half way up the cliff and my legs had been chopped up with Pandanus leaves that were as sharp as razor blades. The night before had been horrific, the Spinifex at the top of the gorge, almost impenetrable.

Kanch may be dead! I'm now sitting at an elevated position in the gorge waiting for help that may or may not come. I have heard a rumour that EPIRB may not work so well in gorges due to their difficulties in transmitting to the satellites. Yesterday evening was horrendous. After the snake, we climbed out of the gorge to get around a sheer wall that made passage below impossible. The terrain at the top was even more unbearable. Neck high spinifex lining car-sized boulders made progress impossibly slow. It created much distress for us both.

In three hours of hiking at the top of the gorge, we covered only half a mile. Dark was coming thick and fast. We had long since run out of water. I expected the traverse at the top of the gorge to be relatively quick. I was becoming very dehydrated. At that time, we came across a gully leading to a ravine. The walls of the ravine and the gully were sheer: 300 hundred feet. We reached a point where Kanch and I could go no further. Kanch was very distressed. For that, I will never forgive myself. Never!.

I started to move Kanch back up the cliff. This was dangerously threatening for the safety of both of us. One slip and we would have fallen 150 feet to our deaths. We reached a point at which we could go no further without taking even more extreme risks. I managed to lift him into a small cave in the side of the cliff where I hoped he would stay overnight. I somehow managed to climb down to get water after having been stuck on the side of the cliff for quite some time. I spent the night by the water. I have heard nothing from Kanch this morning. I suspect that he may be dead of exhaustion or fright.

At 0530 this morning, I put on my boots and gear and hiked six hundred feet into the open gorge. I hope that this will increase the chances of the EPIRB working. The hike was through spider webs and Pandanus so thick that the Pandanus cut like razor blades. I am drenched from having crossed a pool at the end of the side gorge. I hope that help arrives soon.

By nine o'clock on the morning of our tenth day, I was trying to prepare myself mentally for perhaps another fourteen days alone in the Australian outback. As harsh as it might sound, my mind did not keep referring back to the events of the previous evening. If help did not arrive I would have another fourteen days to endure and it was critical that I remain mentally strong. The previous night's challenges had been totally unexpected but there was nothing that I could now do to reverse their having happened. All I could now do was manage the mental impact and prepare for the possibility that the helicopter would not arrive.

I am not sure what I was feeling immediately prior to the appearance of the chopper from around a bend in the gorge. In preparation for what lay ahead, I had cooked up a feed of porridge and digested copious quantities of water to alleviate the still present effects of dehydration. I immediately told the pilot about Kanch,. We boarded the chopper and headed for the top of the ravine to look for him. At this stage I was not sure whether he was still alive as I had not heard from him since the evening before. I prayed he was still okay.

The country at the top of the ravine was every bit as rugged as I had experienced the night before. Upon identifying the point at which we had the evening before commenced our descent, I started down and found Kanch was alive, but distressed and dehydrated and would not let me touch him. I was standing on a ledge that was not more than one foot wide, and the drop was 180 feet straight down. Between his cave and me there was one small ledge of not more than six inches in width.

I recall feeling very fatalistic as I stood on the small ledge and reached into the cave and pulled Kanch out by his tail to the cliff edge of his cave. Pulling Kanch out from the cave and holding him by his skin could pull me out over the edge of the cliff. The challenge rested upon resisting that momentum and managing my own fear to see whether I could get Kanch out.

Having got Kanch out of the cave I now had to get him along the ledge and across the crevice in which we had been stuck the evening before. I salvaged four tiny pieces of rope from the chopper and hauling him up the cliff praying my knots would not come undone. Poor old Kanch did not know what day it was.

I look back on the trip - despite its ending - with a great feeling of satisfaction and a sense of achievement. The country was brutal, and often when I look at Kanch now, I think of the night during which he was stuck on the cliff and my feelings that I might have decided to leave him there had the chopper pilot not come. I still have trouble comprehending the thought.

It took a while, but Kanch seems to have forgiven me and we are friends, but I am not sure he would follow me on such a trip again, and I don’t blame him.

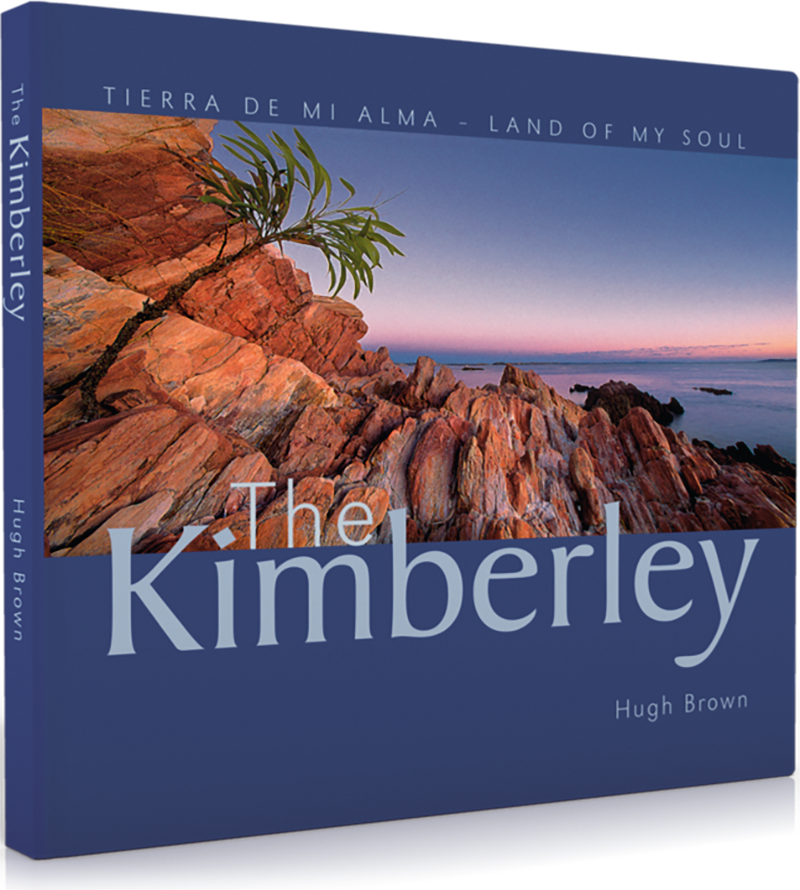

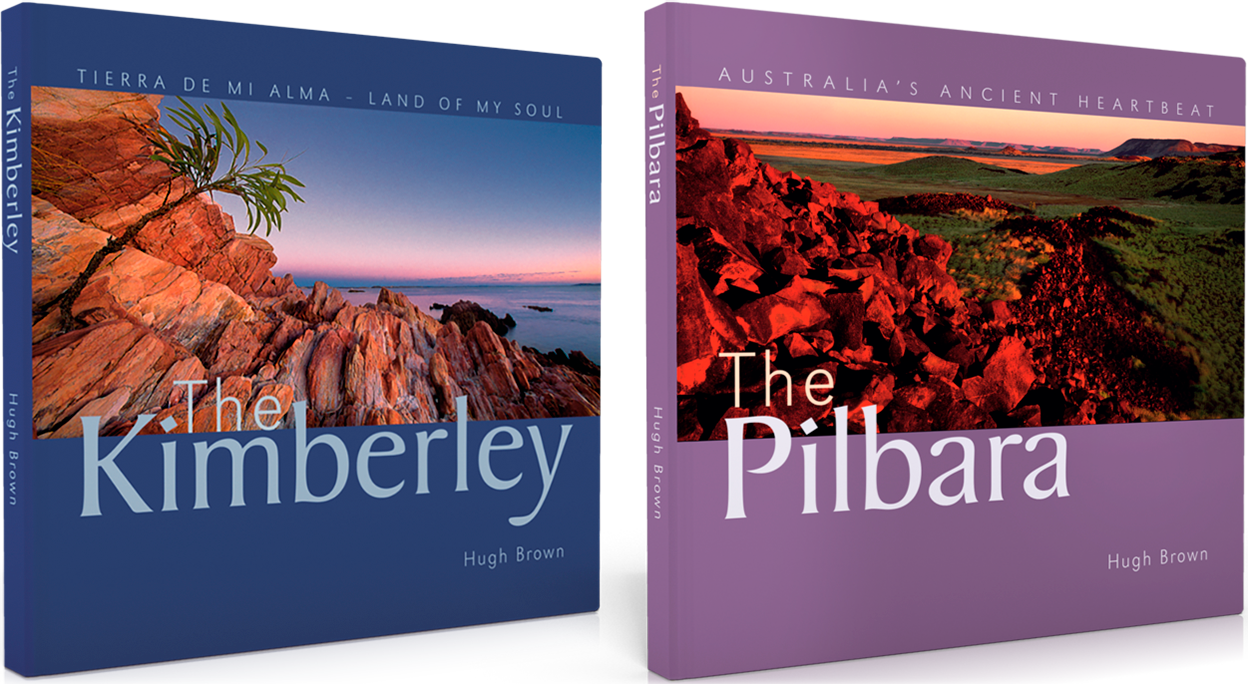

In 2003, while sitting in Froghole Chasm in Purnululu National Park in Western Australia's Kimberley region the idea came about for Hugh's first book: The Kimberley : Australia's Wild Outback Wilderness. This was followed in 2005 by The Pilbara "Outback Australia's Kaleidoscope of Colour", and then in 2006, by Hugh's first hard-cover large format book, The Kimberley: Tierra De Mi Alma - Land of My Soul. In September 2007, Hugh released his second large format coffee table book, The Pilbara: Australia's Ancient Heartbeat. To find out more visit www.hughbrown.com

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ Australia Rock Art Index

→ Introduction to the Australia Rock Art Archive

→ Rock Art of the Kimberley

→ Rock Art Australia (RAA)

→ Dating the Rock Art of the Kimberley

→ Australia's Oldest Known Rock Art

→ Film - Griffith University's Laureate

→ ABC Radio National 'Nightlife'

→

Experts rush to map fire-hit rock art

→ The aftermath of fire damage to important rock art at the Baloon Cave tourist destination, Carnarvon Gorge, Queensland, Australia

→ Studying the Source of Dust

→ Rock Art of Western Arnhem Land

→ Australia's Aboriginal People

→ The Kimberley

→ Out in the Back Country - Hugh Brown

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network