CC BY-SA 3.0

The Peterborough Petroglyphs rock art site in Petroglyphs Provincial Park, known by the Indigenous peoples of the area as Kinoomaagewaabkong or 'The Teaching Rocks', is one of the few petroglyph sites in the Canadian Shield, as well as one of the few rock art sites in Canada, to be designated as a National Historic site (Dagmara Zawadzka 2008).

Petroglyphs Provincial Park, situated near Woodview, Ontario, Canada, northeast of Peterborough, has the largest collection of ancient First Nations petroglyphs in Ontario.

The stone is generally believed to have been carved by the Algonkian-speaking people between 900 and 1100 AD., if not somewhat earlier during the Archaic.

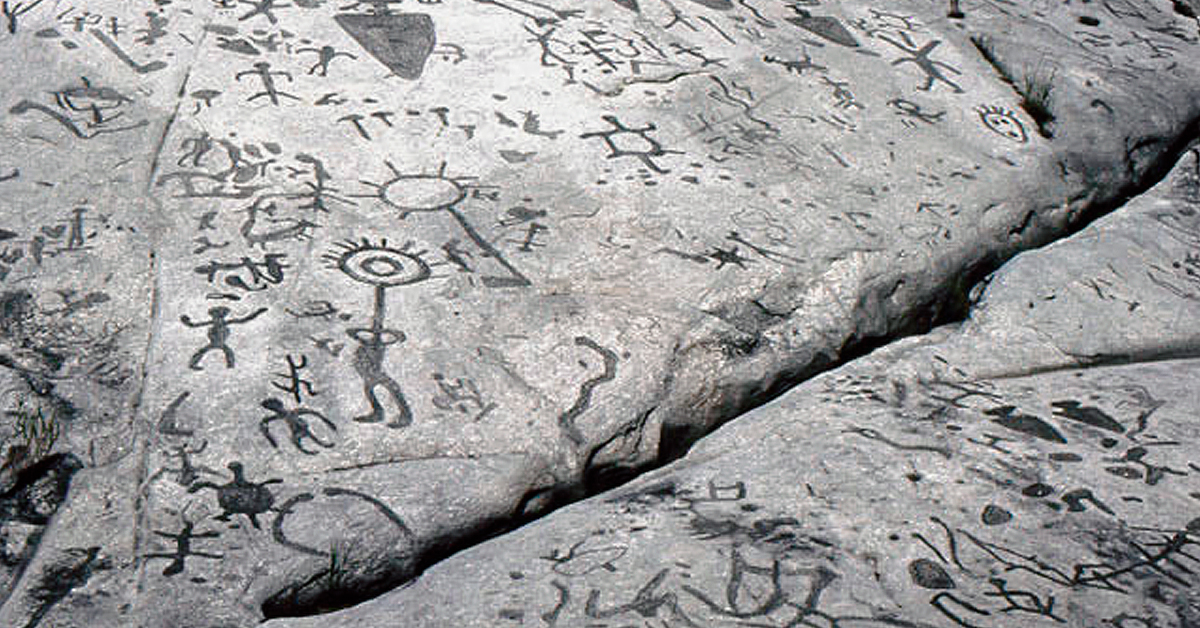

Originally two to three inches deep the 1200 carvings were made using gneiss hammers to incise human figures, animals, and a dominant figure whose head apparently represents the sun, onto the rock.

The petroglyphs were first thoroughly recorded - having been noticed in 1954 by prospectors Everitt Davis, Ernest Craig and Charles Phipps of the Industrial Minerals of Canada - in 1965 by Joan Vastokas of the University of Toronto and Ron Vastokas of Trent University, and presented in their book 'Sacred Art of the Algonkians'. The study was completed in 1967 (Vastokas and Vastokas 1973:10).

The rock site itself is a sacred place, and today is a place of pilgrimage for local Ojibwe people. The deep crevices in the rock are believed to lead to the spirit world, as there is an underground trickle of water that runs beneath the rock which produces sounds interpreted by aboriginal people as those of the Spirits speaking to them.

The rock carvings are now covered by a protective building, and there are interpretive plaques and guides at the site.

In her ICOMOS paper 'The Peterborough Petroglyphs/ Kinoomaagewaabkong: Confining the Spirit of Place' Dagmara Zawadzka of Universite du Quebec a Montreal , describes it as a unique site, which represents one of the largest concentrations of petroglyphs in Canada. The petroglyphs have been carved on a white crystalline limestone outcrop also known as white marble, a rock that is rare in the Canadian Shield where granite and gneiss predominate. The rock outcrop slants gently at a low angle towards the south-east and the engraved area is roughly rectangular measuring 12 by 21 meters (Vastokas and Vastokas 1973, 8-9, 19; Lever and Wainwright 1995, 265). Around 300 clear petroglyphs have been identified. Hundreds more exist at the site, but due to weathering and superimposition they remain largely unidentified.

The carvings, which depict among others animals, human figures and items of material culture (e.g. canoes), are often arranged around natural fissures, rendering them an inextricable part of the rock itself. For example, natural crevices are used to portray what might be the womb and the genitals of a large female figure located on the western side of the outcrop. Sinuous forms interpreted as snakes have also been depicted near crevices and in some instances it appears as if the snakes were coming out of the ground. The site is believed to have been created by Algonquian-speaking peoples and is most likely over a thousand years old (Vastokas and Vastokas 1973, 27), however no absolute dates were ever secured from the site.

In the 1970s, the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Province of Ontario established that the surface of the rock outcrop was deteriorating. In 1980, the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) was asked to determine the causes of deterioration and to advise on proper conservation measures. It was ascertained that the presence of water in the form of precipitation and ground water run-off promotes deterioration. The CCI recommended that a protective structure be built over the petroglyphs in order to shield the site from the weathering effects of acid rain, algae and frost, as well as from vandalism (Wainwright 1990; Lever and Wainwright 1995; Young and Wainwright 1995). The construction began in 1984 and the building, which cost nearly $800,000 CDN (Bahn, Bednarik and Steinbring 1995, 30), was made available to the public in May 1985 (Government of Ontario 2006, 2). The seven-sided, 540 square metres building, which completely encloses the rock, is 10.7 meters high and has a raised cement walkway which surrounds the petroglyphs. The structure is composed of steel beams and glass. The large windows permit the visitor to view the surrounding environment, but more importantly, from a conservation stand point, the windows allow for solar heating of the rock so that it remains dry (Bahn, Bednarik and Steinbring 1995, 33-34; Young and Wainwright 1995, 82, 89).

The building has been lauded as a 'protective' structure that is effective in preserving the petroglyphs. According to the CCI, it is 'one of the most rational, scientific approaches to the preservation and protection of a rock art site in the world' (McLennan 1989, 11 cited in Bahn, Bednarik and Steinbring 1995, 33). However, the structure and its role in the preservation of rock art have been criticized by some scholars. First of all, certain carvings have been damaged during the construction of the building (Bahn, Bednarik and Steinbring 1995, 33- 35; Joan Vastokas, personal communication 2007). Secondly, the flow of the underground stream has also been affected by the construction of the building (Kulchyski 1998, 23; Joan Vastokas, personal communication 2007). Thirdly, Bahn, Bednarik and Steinbring (1995) have observed that the factors believed to promote the deterioration of the site were not adequately assessed by the CCI. Though the building was supposed to protect the site from acid rain, it was found that acid precipitation had little effect at the site (see Lever and Wainwright 1995, 271), and the barbed-wire fence seemed to have offered sufficient protection against vandalism (see Wainwright and Stone 1990, 23-24). The hermetic building introduces a new environment where natural processes, harmful and beneficial to the rock's preservation, cannot take place and where novel conservation problems might arise (Bahn, Bednarik and Steinbring 1995, 38; Bahn 1998, 273). Regardless of the conservation issues, the building fails to reflect Indigenous ideas regarding spirituality and sacred locales where connection with the natural setting is important. It also promotes a static vision of the place.

Zawadzka notes that the building has transformed the site into a museum, which fossilizes the site (Bahn 1998, 273; Kulchyski 1998, 22). Though the museum's ambience does promote respect for the site and Indigenous heritage among visitors, it casts Indigenous heritage as a thing of the past and fails to emphasize the continuous relationship and use of the site by Indigenous people.

The interpretation of the main glyphs offered on the panels at the site also contributes to the stagnation of the meaning of the images, and the panels 'act as tombstones' (Kulchyski 1998, 23). Furthermore, the emphasis on preservation of past through conservation of material culture is not as prominent among Indigenous people where decay is part of the natural cycle (Smith 2006, 286). For example, among the Anishnabeg/ Ojibwa, the 'custom [is] to let old things return to the earth' (Hendry 2000, 32). Furthermore, rock art can be retouched (e.g. in Australia) in order to sustain 'certain values and meaning in a way that the simple existence of the sites could not' (Smith 2006, 54). Therefore the building not only cuts the rock from the surrounding environment and thus the natural spiritual bond, but also imposes a static interpretation of the site.

'The Teaching Rocks' represent the dilemma facing preservation efforts around the world, and emphasize the eternal need for dialogue between cultures in order to reach the delicate balance of maintaining 'the Spirit of Place' and protecting something that cannot - easily - be replaced.

ICOMOS paper 'The Peterborough Petroglyphs/ Kinoomaagewaabkong: Confining the Spirit of Place' Dagmara Zawadzka of Universite du Quebec a Montreal:

→ http://www.icomos.org/quebec2008/cd/toindex/80_pdf/80-W9Fu-143.pdf