The rock art sites contain a variety of both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), and are thought to be linked to shamanism, vision quests, or the search for helping spirits.

All of the rock art sites listed below are located in western Canada. More specifically, the sites can all be found in the southern half of the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia.

Rock art can be classified in two ways; pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), both of which can be found in western Canada. It is believed that rock art is Canada's oldest and most prevalent artistic tradition even though accurately dating many of the sites has proven difficult. Much of the artwork found across the western Canadian provinces can be linked to shamanism, vision quests, or the search for helping spirits. In order to distinguish between different artistic styles, archaeologists have broken the country into broad regions or "style areas" based on geographic location. These include, the Maritimes, the Canadian Shield, the Arctic, the Prairies, and British Columbia. All of the sites listed in this section can be found within the Prairies and British Columbia style areas of the country.

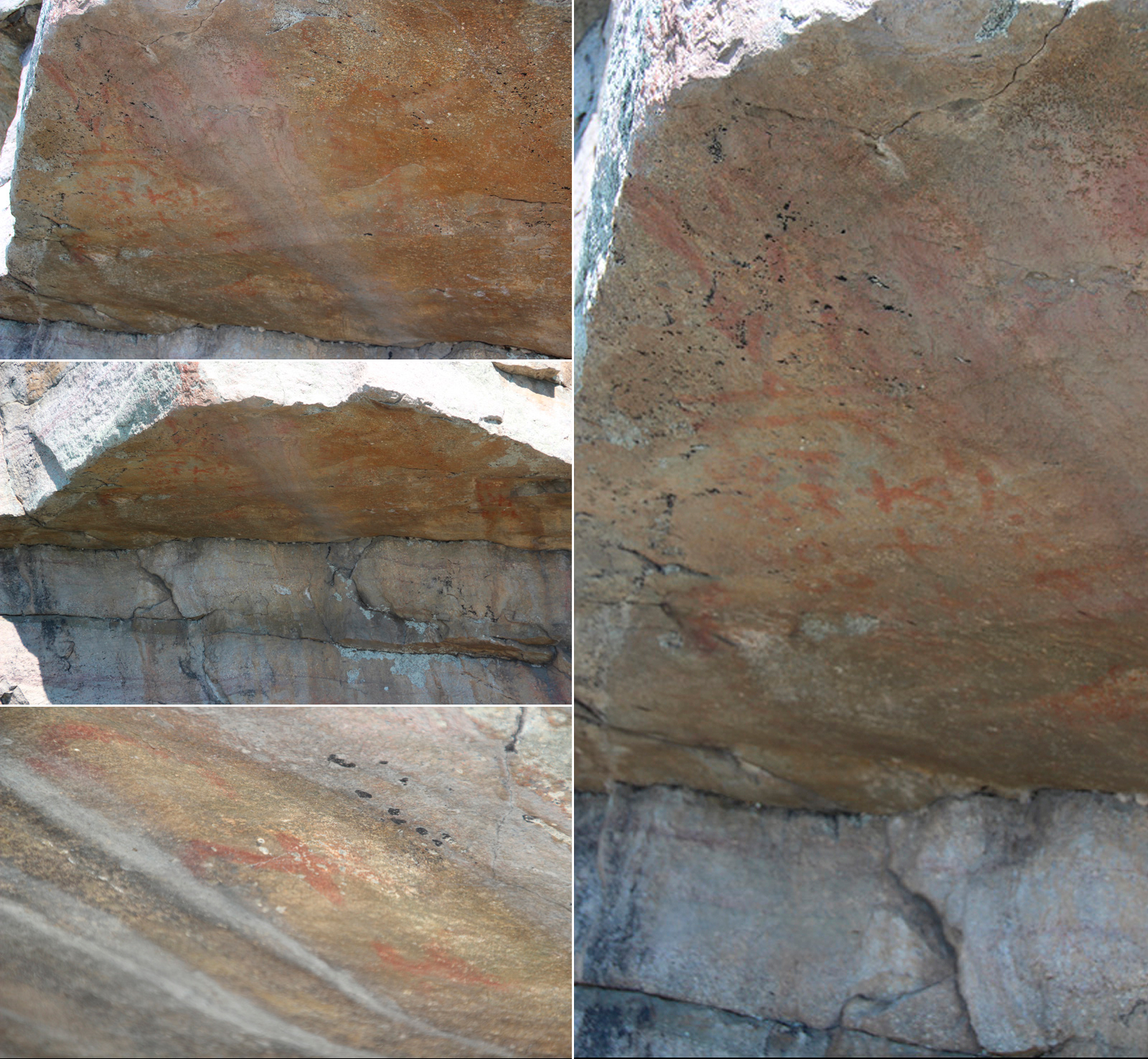

Due to the destruction and slow deterioration of rock art sites, archaeologists with Parks Canada have been tirelessly working with various Aboriginal communities to preserve, protect, and interpret these culturally important sites. One of the project's stated goals is to protect sites using digital photography. The biggest challenge with this, however, is that many sites are disappearing to time, weather, vandalism, or some combination thereof. With the help of a digital enhancement technique known as decorrelation stretch, or DStretch, archaeologists are able to enhance images for better interpretation and understanding. DStretch is a free plugin for ImageJ software that was created by Jon Harman. Both ImageJ and DStretch are available for free download. Many of the photographs included in the section below have been enhanced using DStretch.

This site contains a single petroglyph and a single pictograph. The petroglyph depicts the sun, while the pictograph is of a shield-bearing warrior (above). Unfortunately this is all the information I have about the history of this site.

The pictographs found on the smooth canyon walls are estimated to be between 500 and 1,300 years old. There are many interpretations as to who painted them and how they arrived at this location. The most popular theory is that they were created by the Hopituh Shi-nu-mu People (Hopi for short) who visited the area. According to legend, the Hopi sent off members of their tribe in the four directions with the intention of meeting again at a common place, which ended up being present-day Arizona. The artwork depicts both human-like figures and animals. There is also one of the flute player, known as Kokopelli, which is a traditional symbol of the Hopi People. In the Hopi culture the Kokopelli represents the traveler and fertility. It is believed that these pictographs are linked to the ones found near Grassi Lakes (see next entry). Unfortunately most of the paintings have been damaged by weather, time, and people touching them. The oils on our skin will destroy rock art and it's also the reason why the paintings in the photographs look glossy or waxy.

As mentioned above the pictographs located near Grassi Lakes are thought to have been painted by the Hopi people. They are estimated to be more than 1,000 years old. One of the pictographs depicts a human figure holding a large ring. It is believed that this figure represents a Medicine Man, which happens to be one of the most famous Hopi legends. The Hopi People believe that Medicine Men were not only healers, but were also considered to be seers and philosophers within their own tribes. The artwork at this site is in better condition than Grotto Canyon, but does show signs of weathering.

The paintings on the Big Rock near Okotoks are estimated to be anywhere from hundreds to thousands of years old. The Blackfoot People used the rock as a landmark for finding a crossing over the Sheep River before European settlers arrived. There are countless First Nation legends associated with the rock, some of which were relayed through pictographs painted onto its surface. According to local Elders, one such painting depicts a journey. The arrows point in the direction of travel (north), while the moons, or circles, tell the time it took to complete the journey. There are seventeen moons in total, meaning it likely took seventeen months to complete the trek. The symbols and figures at the top of this pictograph may indicate why the journey was made.

Archaeologists believe these pictographs are over 300 years old and were painted by either the Kootenai or Salish First Nation People. Due to their isolated location it is believed that these pictographs are from a successful completion of a Vision Quest ceremony. The site was originally home to a large collection of artwork, but a rockslide in 1975 destroyed most of them. Today there are two very distinct paintings with a few more close-by that have been eroded by time and weather.

There are two common theories about what the pictographs at this site represent. Archaeologists from the Glenbow Museum feel that the pictograph depicts shield-bearing warriors (similar to the one at the Cochrane Ranche Site) before the introduction of horses.

A member of the Blackfoot community, however, feels that the artwork is telling the legend of the Wedding of Napi.

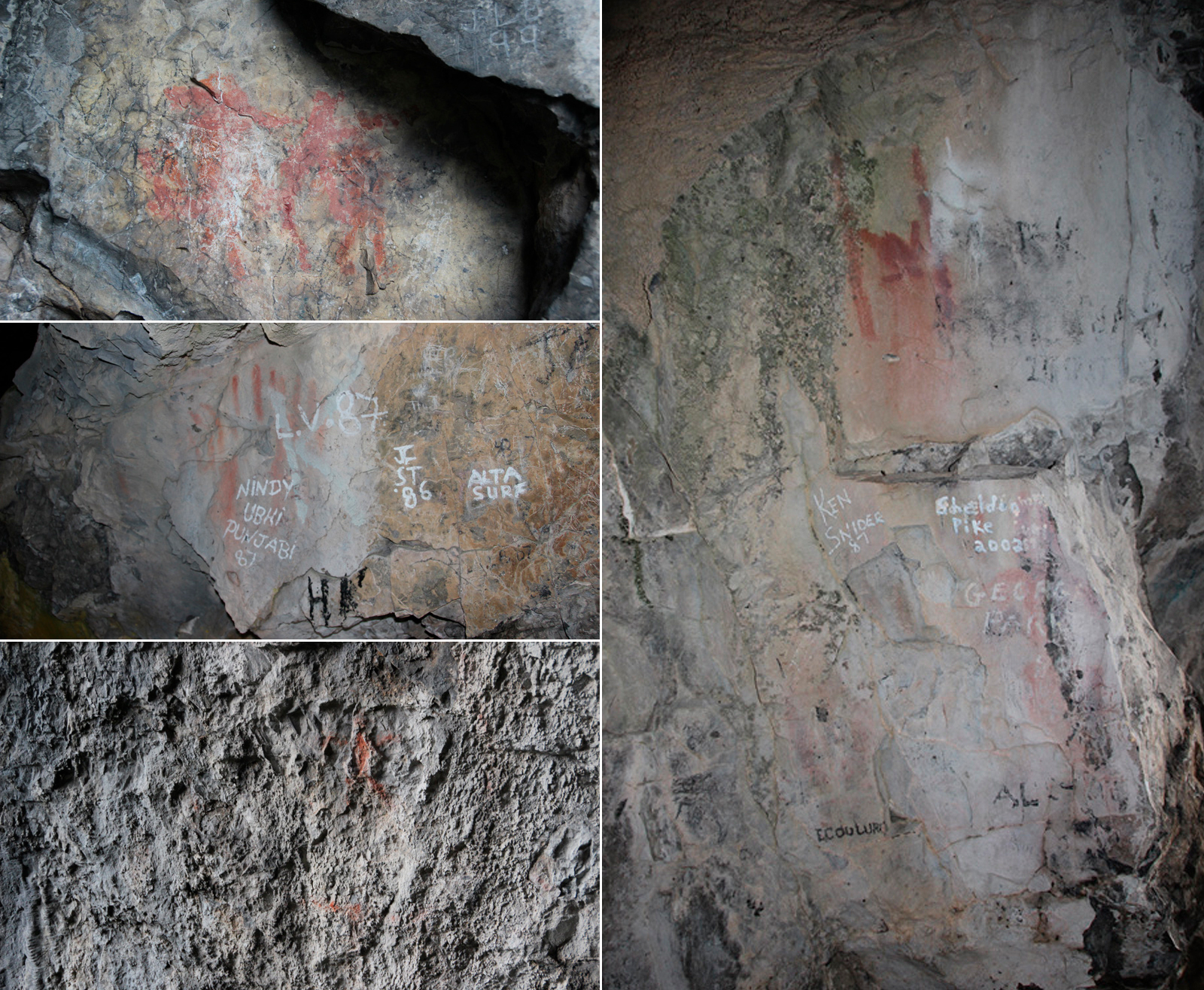

This site holds great spiritual significance for First Nation people. The cave was known to the Blackfoot People as, "where the Oldman comes out of the mountain", referring to the Oldman River. The entrance to the cave was once covered with pictographs, but sadly today they have been badly vandalized by common graffiti and most are all but indecipherable.

The pictographs found on the canyon walls within Roderick Haig-Brown Provincial Park were most likely painted by the Shuswap People and are closely related to other sites in the area (i.e. Copper Island, Magna Bay).

These pictographs are believed to have been painted long before the arrival of Europeans and if you search nearby you will find depressions in the ground that were once kekulis, or pit houses; also built by the Shuswap People.

Like the pictographs in Roderick Haig-Brown Provincial Park, these are believed to have been painted by the Shuswap People. Unfortunately I do not know anything else about this site, only that it is visible from the water.

Much like the Magna Bay site, I don't know the history of these pictographs. The island likely held great significance for the Shuswap People and according to legend Ta Lana, the great bear, sleeps under the island in a large cave. Most of the pictographs on the island have been lost to time, weather, and/or vandalism as only faint, red smudges remain.

This site of Michel-Natal in (also known as McGillivray Shelter) in British Columbia has two separate human-like figures that are slowly fading away.

From what I've read these pictographs are typical of traditional Columbia Plateau Art and it is believed they represent dreams and the acquisition of spiritual power, likely obtained during a Vision Quest.

This site, commonly known as the Braeside Site, is near the shoreline of Skaha Lake. Considering the size of the panel, it is believed that many different people added to this painting over many years. Unlike a lot of paintings that were related to puberty rituals, Braeside may have been a record of a particularly successful hunt or hunts. It's possible that this stretch of Skaha Lake was prime hunting territory and after a successful hunt it was common to stop at Braeside and share their story through art. There is also a theory that involves magic where painting a picture of a successful hunt could help ensure a successful hunt would happen.

Much like the Magna Bay site, I don't know the history of these pictographs. The island likely held great significance for the Shuswap People and according to legend Ta Lana, the great bear, sleeps under the island in a large cave. Most of the pictographs on the island have been lost to time, weather, and/or vandalism as only faint, red smudges remain.

→ Parks Canada Archaeology

→ DStretch Homepage

→ Rock Art in Canada

→ Historic Canada

Name: Tyler Dixon

Location: Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Age: 31

Profession: Teacher

Background: I am originally from Saskatchewan, but have called Calgary home for over eight years now. I am a high school teacher with the Calgary Board of Education and my passions lie within the outdoor and physical education fields. I volunteer with the GOT Parks initiative, which aims at reconnecting Canada's youth with our national, provincial, and territorial parks, and Calgary Is Awesome, where I am the Outdoor Editor in charge of reporting everything that makes Calgary's enormous backyard an adventurer's dreamland. In my free time I enjoy numerous outdoor activities, such as hiking, mountain biking, paddling, camping, cross-country skiing, and snowboarding, as well as team sports, travelling, photography, spending time with good friends, and being at home with my wife and our dog, Rome.

→ Blog: http://getmeoutdoors.blogspot.ca/

→ Twitter: http://twitter.com/tcdixon3

→ Instagram: https://instagram.com/tcdixon3/