by Dr. George Nash - Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Bristol

High within the secluded rock shelters of northeastern Brazil exists some of the world's most intriguing ancient rock art. It has the potential to redraft the very story of modern humans, as member of the Rock Art Network and rock art specialist Dr. George Nash explains.

The National Park of the Serra da Capivara in the state of Piauí, northeast Brazil, became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1991. It covers 129,140 hectares, and has at least 1,300 archaeological sites within its bounds, in addition to its diverse wildlife and outstanding geology.

The peripheral areas of the National Park comprise a flat, partially cultivated brushwood plateau known as Sertâo. This semi-arid landscape surrounds a dramatic upland massif of exposed and weathered Silurian sandstone, worn smooth first by water then by wind over geological time. Within the hinterlands between the sandstone massif and the plateau is scrub forest, known as caatinga. In geological terms, the sandstone massif was formed some 430 million years ago when it was a warm sea; the sediments within the sandstone formed the seabed and the extensive pebble conglomerate deposit above it, representing a later overlying ancient beach. Hidden at the base of this giant massif is a series of rock shelters and overhangs. It is within these natural cathedral-like places that the rock art sites have been found.

The nearby town of Sao Raimundo Nonato is home to the scientific research centre and museum, The Fundaçäo Museu do Homem Americano (The Museum of American Man Foundation), founded in 1986 by French and Brazilian scientists. This is where much of the recording and dating work has been undertaken and coordinated.

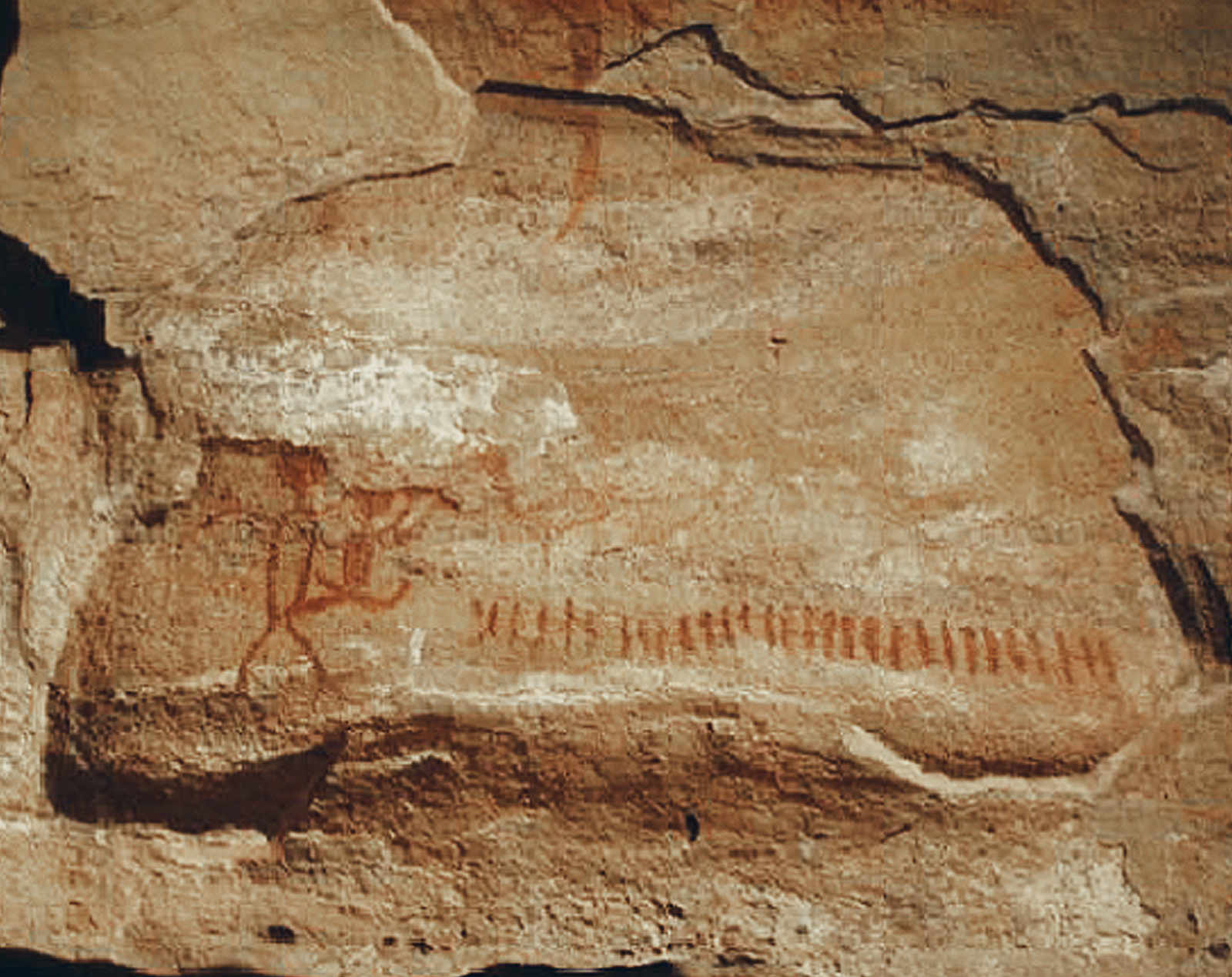

Prior to the area’s designation as a National Park, the rock art sites were difficult, and often dangerous to enter. In ancient times, this inaccessibility must have heightened the importance of the sites, and indeed those who painted on the rocks. This ‘perilous’ rock art tends to be painted in various shades of red using ochre (haematite), which naturally bleeds from the surrounding exposed rock outcropping;though occasionally yellow (limonite) and grey pigments were also used. Each panel (or canvas) usually takes the form of a long linear block of images, arranged about 0.5m to 2m above the original floor, and extending some tens of metres long. Occasionally, the panel fills the whole length of the naturally formed rock-shelter or overhang. Most images appear to be strategically placed, usually within natural depressions, either cutting into the rock surface or in eroded hollows.

Wild animals and human figures dominate the rock art, and are incorporated into often-complex scenes involving hunting, supernatural beings, sexual activity (including bestial scenes), skirmishing and dancing. The artists depicted the animals that roamed the local ancient brushwood forest: red deer, armadillo, capivara (a large rodent), jaguar, lizard, tapir, and the giant rhea (a type of ostrich, now extinct), among others. Of these, red deer is the most common. Sometimes the animal is simply painted in outline, other times it is totally infilled, or internally decorated with geometric patterns or rows of dots. The large mammals are usually painted in groups and tend to be shown in a running stance, as though trying to escape from hunting parties.

Due to the favourable climatic conditions, the imagery on many panels is in a remarkable state of preservation. Despite this, however, there are serious conservation issues that affect their long-term survival. The chemical and mineral qualities of the rock on which the imagery is painted is fragile and on several panels it is unstable. As well as the secretion of sodium carbonate on the rock surface, complete panel sections have, over the ancient and recent past, broken away from the main rock surface. These have then become buried and sealed into sometimes-ancient floor deposits.

Of course, dating the art is extremely difficult given the total absence of organic pigmentation that might be C-14 dated. However, there are a small number of sites that are giving-up their secrets through good systematic excavation. Thus, at Toca do Boqueirao da Pedra Furada, rock-art researcher and founder of FUMDHAM Níéde Guidon, managed to obtain a number of dates. In a deep area of excavation, she located fallen painted rock fragments, which she contextually dates to at least 36,000 years ago. Along with the painted fragments, crude stone tools were found made from locally formed quartz pebble conglomerates. Also surviving the harsh acidic soils were coprolites (fossilised human faeces). When analysed, these only revealed dates of between 6,500 and 5,000 BC.

ceiling at the Toca da Entrada do

Pajaú rock art shelter

surrounds the Toca do Boqueirao da Pedra

Furada rock art shelter

Pedra Furada rock art shelter in the

Serra da Capivara

dominate the rock art of the

Serra da Capivara in Brazil

a sex scene at Toca do Boqueirao

da Pedra Furada, Brazil

Nonetheless, this is not the only site to provide early dating evidence of the likelihood that the people were in Brazil far earlier than previously thought: other sites such as Tocada Entrada do Pajaú and Toca do Paraguaio, both in the Serra da Capivara National Park; Cueva de las Manos (Cave of Hands) in Patagonia, Argentina ; and the hearths near the Monte Verde sites in Los Lagos in Chile, have all yielded ancient datable deposits that greatly predate 10,000 BC- the assumed date that people first moved into North America.

At Toca do Boqueirao da Pedra Furada, in 1973, Níéde Guidon revealed a remarkable set of images painted in a variety of colour pigments.The rock art is located underneath a cathedral-like 150m cliff. A series of excavations between1978 and 1987 and extending some 5m below the surrounding floor level obtained over 60 dates from mainly undisturbed archaeological horizons; several of these datable deposits actually covered rock art, abutting the rock-shelter wall. Among the finds were around 7,000 lithic artefacts, 600 of which were made from quartz and were relatively dated to the Pleistocene era. Also discovered were a series of datable hearths, the earliest dated to 46,000 BC, arguably the oldest dates for human habitation in the Americas.

However, these conclusions are not without controversy. Critics, mainly from North America, have suggested that the hearths may in fact be a natural phenomenon, the result of seasonal brushwood fires. Several North American researchers have gone further and suggested that the rock-art from this site is no earlier than 3730+90 years BP (before present), based on the results of limited radiocarbon dating.

Equally compelling are several dates that have been obtained from calcite formations, which have covered the rock art from the Toca da Bastianna rock shelter. The sampling of this deposit using thermoluminescence (TL dating) revealed an astonishing date of 34,000 years BC. It is more than likely that these painted fragments are much earlier, thereby further reinforcing the possibility of a pre-Clovis (pre-c.10,000 BC) tradition in South America. Adding further fuel to the debate is the fact that the artists tended not to draw over old motifs (as often occurs with rock art), which makes it hard to work out the relative chronology of the images or styles. However, the diversity of imagery and the narrative the paintings create from each of the many sites within the National Park suggests different artists were probably making their art at different times, and potentially using each site, over many thousands of years.With fierce debates raging over the dating, where these artists originate from is also still very much open to speculation. The traditional view (namely the Clovis First Theory) is that pioneering settlers, crossed the Bering Straits from Siberia to Alaska at around 10,000 BC and spread southwards into Central and South America. But this rather simplistic explanation ignores all the aforementioned early dating evidence from the South American rock art sites. In a revised scenario, some palaeo-anthro-pologists are now suggesting that modern humans may have migrated from Africa using the strong currents of the Atlantic Ocean some 60,000 years or more ago, while others suggest a more improbable colonisation coming from the Pacific Ocean.

Yet, while either hypothesis is plausible, we have still not found any supporting archaeological evidence between the South American coastline and the interior. Rather, based on the evidence from Brazil, it seems possible that there were a number of waves of human colonisation of the Americas occurring possibly over, say, a 60,000-100,000 year period, roughly commencing sometime after modern humans started to colonise the earth; again probably using the Bering Straits as a land-bridge to cross into the Americas. Despite the compelling evidence from South America, it stands alone: the earliest secure human evidence yet found in North America only dates to 12,300 years BC (namely from the recent excavations at Paisley Caves in southern Oregon that have uncovered lithics and coprolites of that date).

So this is a fierce debate that is likely to go on for many more years. However, the splendid rock art and its allied archaeology of northeast Brazil, described here, is playing a huge and significant role in the discussion. This art - from the ochre-red deer to the ‘children around the maypole’ - is tantalisingly poised to redraw the very picture of our human story.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ South America Rock Art Archive

→ Rock Art of Serra da Capivara

→ Rock Art of Pedra Furada

→ World Heritage Site of Cueva de las Manos (The Cave of the Hands)

→ Rock Art of Bolivia

→ The Rock Art of Santa Catarina

→ The Checta Petroplyphs - Peru

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network