The preservation project was to involve taking a mould of the carvings from which to create a limited edition of aluminium casts, one of which would be gifted to the town of Agadez near the archaeological site, another of which would be located at the National Geographic headquarters in Washington D.C. A further element of the preservation project was to sink a water well in the area in order to support a small Tuareg community who would be responsible for guiding tourists at the Dabous site.

In the heart of the Sahara lies the Tenere Desert. 'Tenere', literally translated as ‘where there is nothing’, is a barren desert landscape stretching for thousands of miles, but this literal translation belies its ancient significance - for over two millenia, the Tuareg operated the trans-Saharan caravan trade route connecting the great cities on the southern edge of the Sahara via five desert trade routes to the northern coast of Africa.

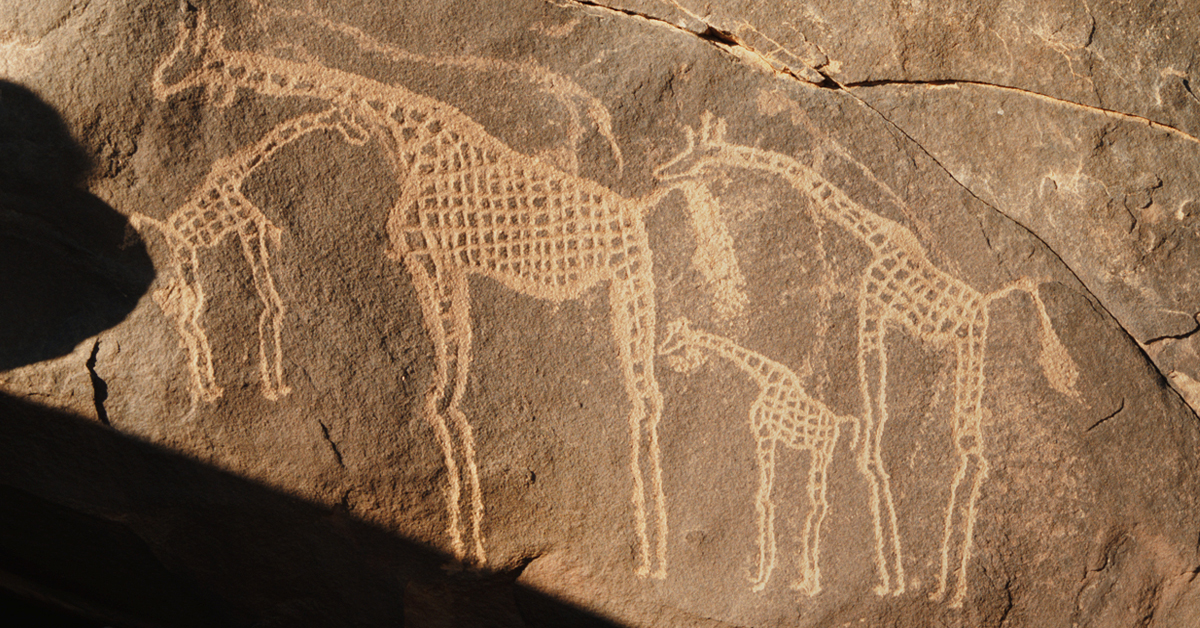

And before the Tuareg? Life in the region now known as the Sahara has evolved for millennia, in varying forms. One particular piece of evidence of this age-old occupation can be found at the pinnacle of a lonely rocky outcrop. Here, where the desert meets the slopes of the Air Mountains, lies Dabous, home to one of the finest examples of ancient rock art in the world - two life-size giraffe carved in stone. They were first recorded as recently as 1987 by Christian Dupuy. A subsequent field trip organised by David Coulson of the Trust for African Rock Art, brought the attention of archaeologist Dr Jean Clottes, who was startled by their significance, due to the size, beauty and technique.

The two giraffe, one large male in front of a smaller female, were engraved side by side on the sandstone’s weathered surface. The larger of the two is over 18 feet tall, combining several techniques including scraping, smoothing and deep engraving of the outlines. However, signs of deterioration were clearly evident. Despite their remoteness, the site was beginning to receive more and more attention, as these exceptional carvings were beginning to suffer the consequences of both voluntary and involuntary human degradation. The petroglyphs were being damaged by trampling, but perhaps worse than this, they were being degraded by grafitti and fragments were being stolen.

By chance, a year earlier saw the publication of 'Zarafa' by Michael Allin, depicting the fascinating tale of a giraffe from the Sudan being led across France in 1826 – the Dabous giraffe would travel to France nearly two hundred years later, but in a slightly different fashion.

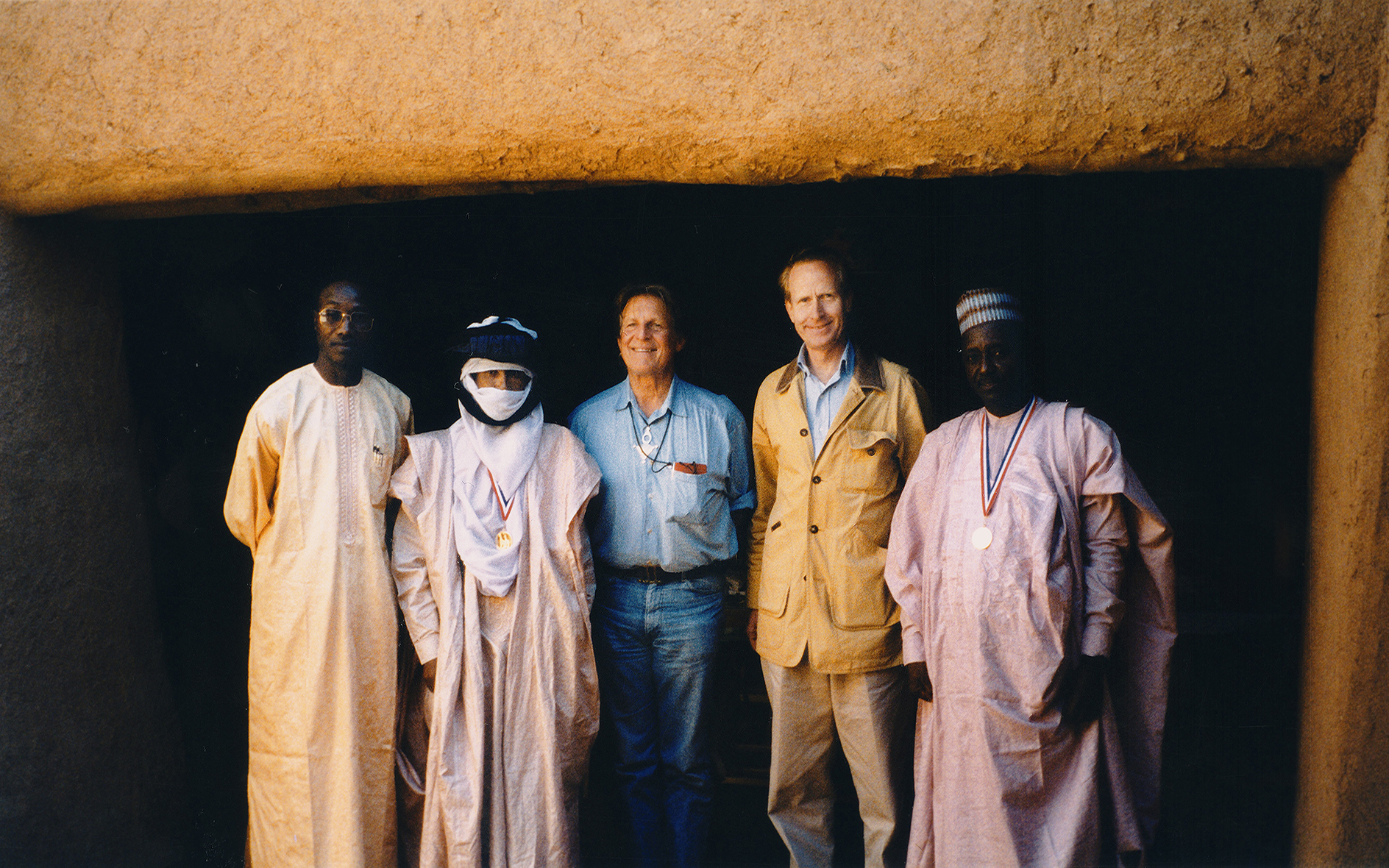

One of the major aims of the Bradshaw Foundation is to preserve ancient rock art, but with a project of this nature and scale, we obviously needed permission from both UNESCO and the government of Niger. Moreover, it was important to ensure that the project would be carried out at the grass-roots level, with full involvement of the Tuareg custodians. Finally, consideration of the future preservation had to be catered for, and for this reason a well was sunk near the site to provide water for a small group to live in the area, a member of which would act as a permanent guide - to show where to mount the outcrop, where to best view the petroglyphs without walking on them, and to ensure no damage or theft.

Although there was clear evidence of sedentary life involving hunting and gathering, little did we realize we were standing on top of further evidence of this past life-style that reflected a greener Sahara, and evidence which would later provide clues as to who the original artists of the giraffe carvings just to the south were and when they were carved. At this time Dr Jean Clottes estimated that the carvings were between 7,000 and 10,000 years old.

First came the Kiffian, who grew up to 2 metres tall and hunted wild game, the bones of which were found nearby. They vanished when the Sahara entered a dry spell about 8000 years ago, to be replaced by the shorter, leaner Tenerians when the rains returned a millennium later. Bones and artefacts imply that they herded cattle and hunted fish and wildlife. Presently it is not possible to say with any certainty which culture – the Kiffian or the Tenerian - was responsible for the carvings.

How were the carvings created? 10,000 years ago there was no metal - this was well before the Bronze Age - so how did the artists carve the lines? They must have used a harder material like flint to carve the softer sandstone of Dabous. The desert sands surrounding the outcrop are covered with numerous chisels of petrified wood, perfect for wearing away grooves and then polishing the surface. This in itself magnifies the significance of Dabous, for its scale and craftsmanship, and therefore the amount of time it must have taken to execute.

The selection is important - the carvings cannot be seen from the ground, but only by climbing onto the outcrop. Moreover, the area that was used - the stone canvas - had been prepared for the carvings.

Was it because these tall and graceful animals were perceived by a palaeolithic society as especially impressive: chimeric figures, with the face of a camel and the spots of a leopard, markings that had been portrayed with such attention to detail in the carvings; animals with a speed and ferociousness in self-defence that belied their unhurried gait? There is no other animal like a giraffe.

Or, perhaps their unique attribute resided in their unusually large eyes which may have attracted the attention of ancient cultures. The giraffes’ ability to see great distances, beyond scent or sound, would not have gone unnoticed, and may have become a metaphor for foresight and prediction.

If this gift could be tapped by the group's priest or shaman, it would have a great influence. Perhaps this explains the thin line leading from each giraffe mouth to the top of the head of small human like figures.

Another obstacle to consider was prejudice. There is a great deal of suspicion surrounding attempts at rock art moulding. This has come about due to the fact in the majority of cases mouldings were made by people who did not entirely master the necessary techniques, which subsequently degraded the originals. Indeed, about 30 miles from the Dabous site, there are traces of such vandalism. For this reason the Merindol team, based in France, were sent out on an exploratory expedition to carry out tests of the silicon polymer material on the rock surfaces where no petroglyphs were present.

There is also the opinion that moulding changes the chemistry of the rock surface and prevents any future varnish study for possible dating methods. This is debateable, but to take this in to consideration, we devised a system of clay patches to go between the rock surface and the silicon polymer paste.

Finally, consideration had to be given to the artistic and spiritual heritage of the present day custodians of this rich and beautiful art. There is an undoubted need to be sensitive, but balanced against the preservation of an ancient legacy of an economy that is both financially and technically unable to provide it for themselves.

In November 1999 the remote outcrop was transformed into a hive of activity, as the team - the craftsmen of Merindol and the local Tuaregs - commenced the slow and complex process of taking the mould. For the silicone to set it was vital that the stone was cleaned, the clay patches applied, and then sealed. The months of planning and preparation, combined with perfect weather conditions, meant that the moment had finally arrived, when we could apply the silicon and begin to take the mould.

The wet silicon was daubed on meticulously, capturing every minute detail of the carving. Finally complete, a metal frame was laid over the silicon to provide a stiff protective backing for the rubber mould, secured by quick-setting plaster of paris. As the silicon mould lay on top of the giraffe carving, the success of the project hung in the balance. Inch by inch the team carefully peeled it back from the stone. Three hours later, we were able to cut it into sections and lower them to the desert floor where they were reassembled upside down on the platform.

With the moulding process now complete, it began its journey to the foundry in France where the negative mould would be turned into a plaster positive. This would then be completely surrounded by fine sand and injected with gas to petrify the sand. Removing the plaster positive would leave the negative mould, into which would be poured molten aluminium. Once cooled, the hardened sand would be hammered off, revealing the aluminium cast positive. The actual piece was so big that it was cast in 9 panels, which would bolt together.

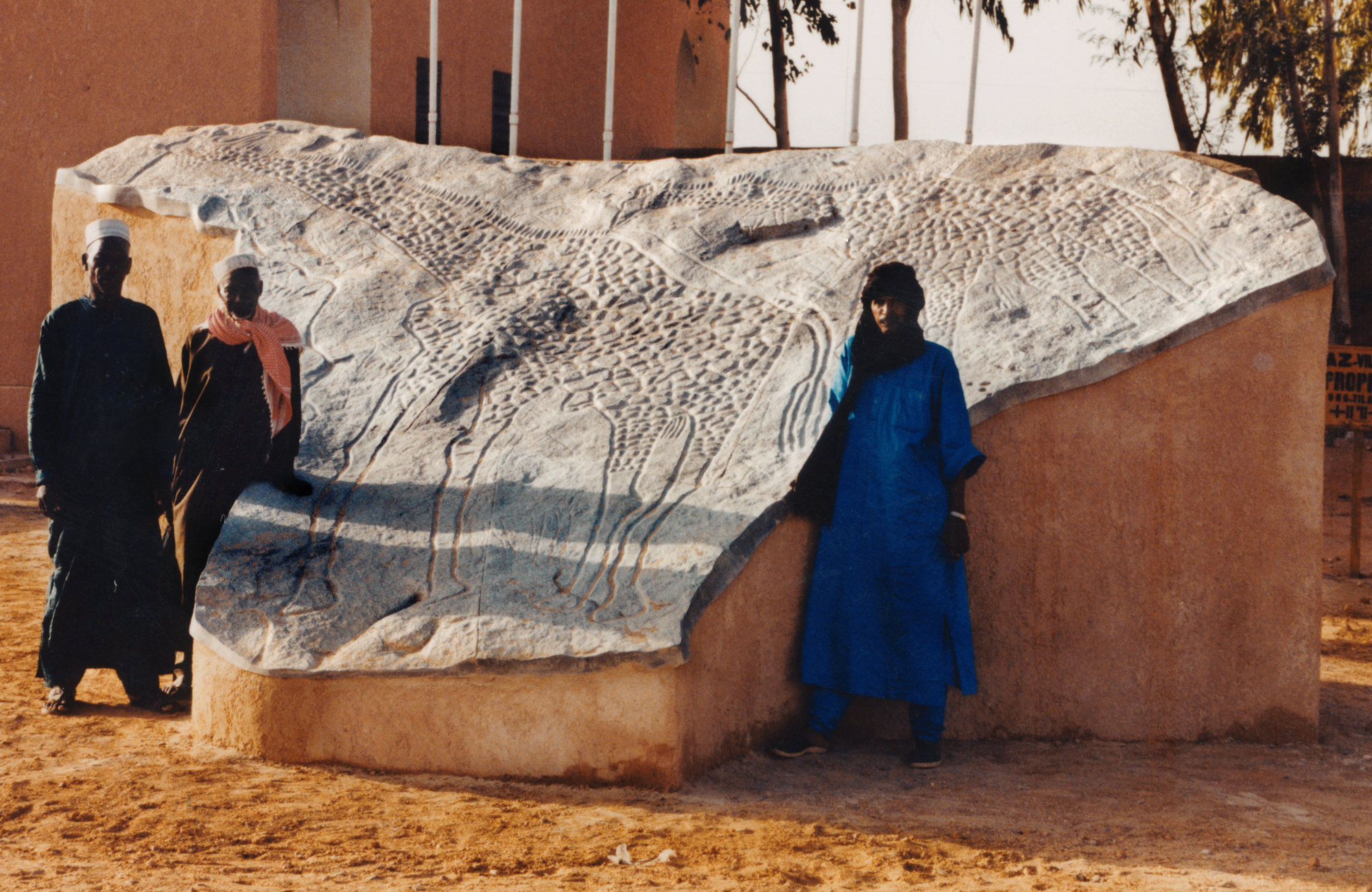

The true home of the giraffes carvings is the Sahara, and therefore it was appropriate that the first cast should return to Agadez, the small desert town near the actual site, as a lasting monument. The cast, located at the airport, stands as a symbol of the rich heritage of rock art that the area holds, a heritage that hopefully will be preserved for future generations.

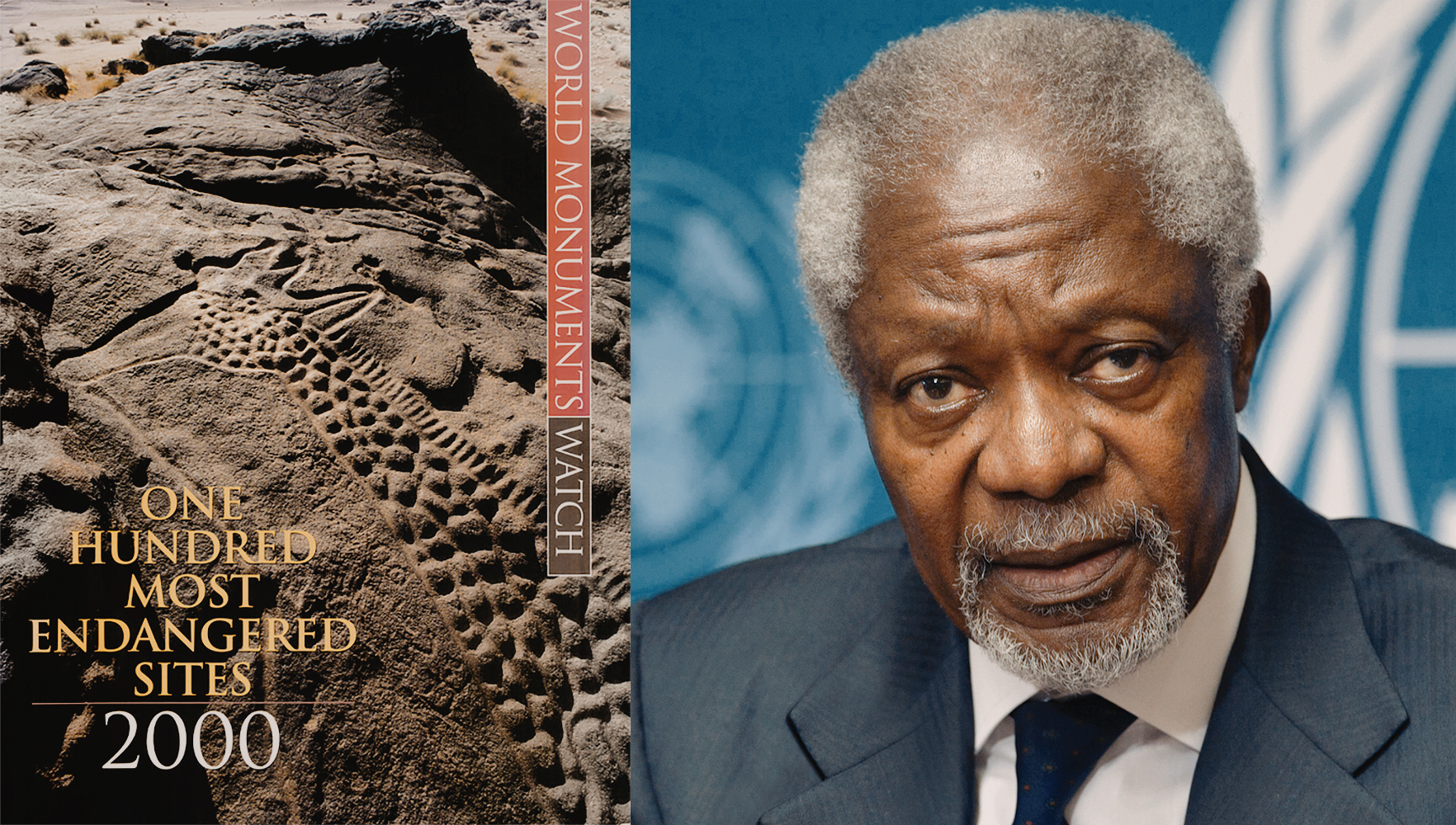

In 2000 the giraffe carvings of Niger in Africa were declared one of the the hundred most endangered sites by the World Monuments Watch, and featured on the cover of a publication listing sites in danger around the world. The giraffe carvings had suffered the consequences of both voluntary and involuntary human degradation. The petroglyphs were in danger of being damaged by trampling, degraded by graffiti, and fragments being stolen.

This preservation project involved making a mould of the carvings, from which a limited edition of aluminium casts were produced. The first edition cast was gifted to the town of Agadez in Niger, near the archaeological site, in order to draw attention to the importance of the rock art of the country and the need for its protection.

A cast of the head of the male giraffe from the Dabous carvings was donated by the Bradshaw Foundation to the Yinchuan World Rock Art Museum of the People's Republic of China. Located in Helankou, near Yinchuan, the capital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, the museum nestles at the feet of the spectacular Helan Mountains, famous for its ancient rock carvings.

The timing of the Field Trip to Helankou was chosen to coincide with the 2010 Third Annual Rock Art Festival & Seminar, held at the Yinchuan Museum and the Northern Nationalities University in Yinchuan. The opening speeches were followed by the exchange of gifts – the Dabous cast and the petroglyph rubbing of the Helankou 'Sun God' - between the Foundation & the Museum.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ The Rock Art of Africa

→ Tassili n'Ajjer

→ The Dabous Giraffe Petroglyph, Niger

→ The Rock Art of Niger

→ The Rock Art of Namibia

→ The Rock Art of South Africa

→ Hunter-gatherer rock art sites in Africa

→ Gilf Kebir - Cave of Swimmers

→ Animals in Rock Art

→ Rock Art of Western Central Africa

→ Where is the Oldest Rock Art?

→ Africa's World Heritage Sites (Film)