The 10-day colloquium gathered 24 experts from around the world, including professional rock art researchers and conservation specialists as well as creative thinkers who use rock art in a variety of ways, such as communicating its values to the public through film, deriving artistic inspiration from it, management by traditional owners, and sustainable tourism.

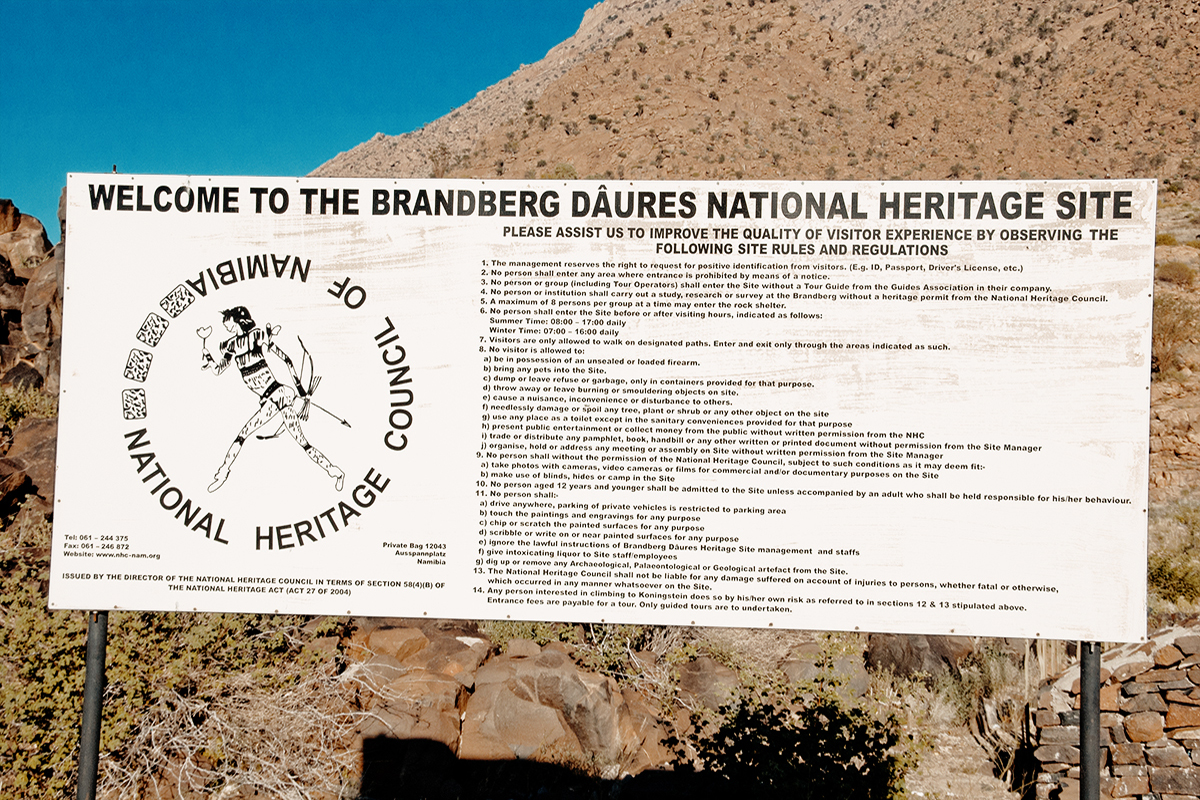

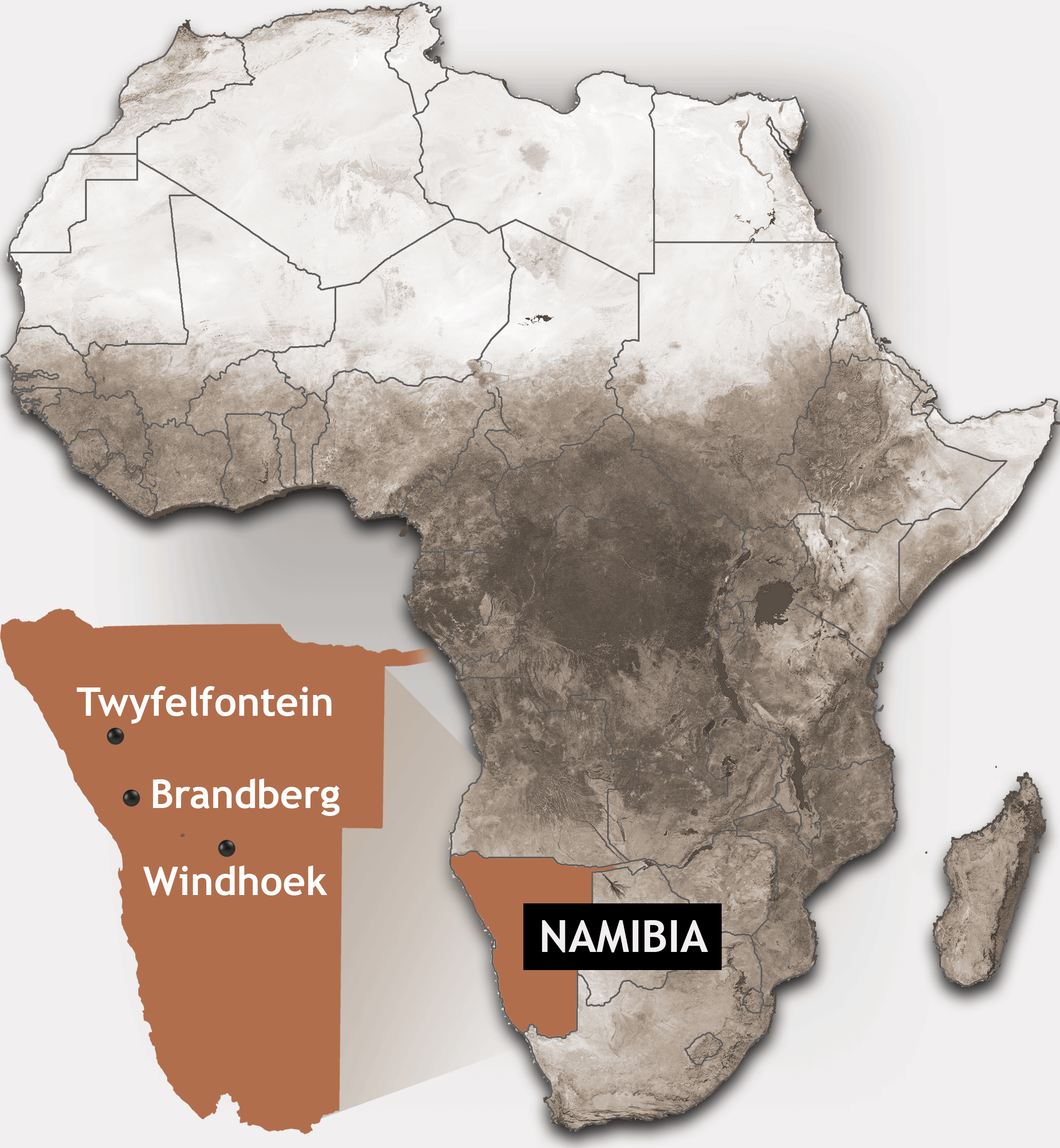

Beginning in the the Namibian capital city of Windhoek, the colloquium was structured around papers, presentations and discussions by all those attending. These continued throughout the course of the event, punctuated by two rock art site visits to the Brandberg and the World Heritage Site of /Ui- //aes, also known as Twyfelfontein. Wrap-up sessions took place in Windhoek.

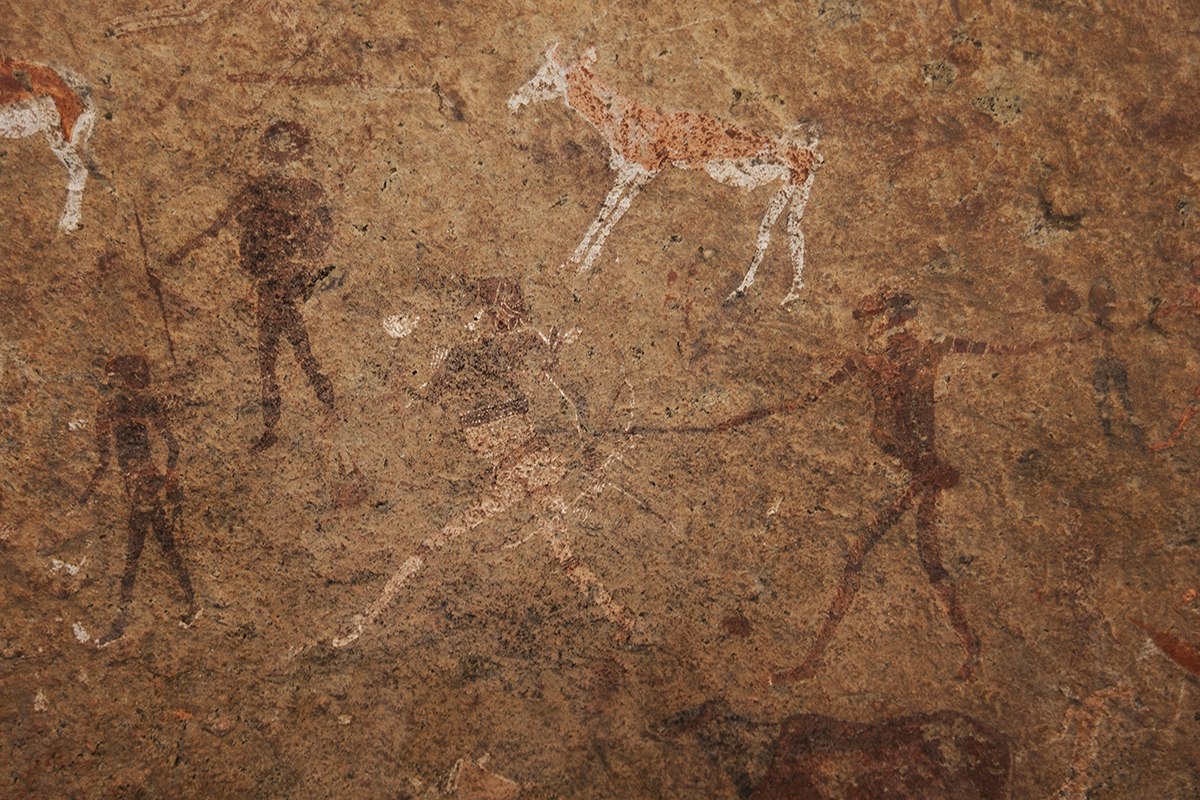

The Brandberg Mountain is located in former Damaraland, now Erongo, in the northwestern Namib Desert, some 50 km from the coast, and covers an area of approximately 650km. It dominates the landscape and can be seen from a great distance, with its highest point, the Königstein (German for 'King's Stone'), standing at 2,573m. above sea level. The Brandberg is a site of great spiritual significance to the Damara San (Bushman) people. Regarding rock art, the most famous site is the so-called 'White Lady' rock painting, located on a rock face with other artwork under a small rock overhang, in the Tsisab Ravine at the foot of the mountain. The Brandberg Mountain, including the higher elevations, contains more than 1,000 rock shelters, with an estimated 45,000 rock paintings.

Most of the rock paintings have been painstakingly documented by Harald Pager, who made tens of thousands of hand-traced copies. Pager's work was posthumously published by the Heinrich Barth Institute, in the six volume series 'Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg' edited by Tilman Lenssen-Erz.

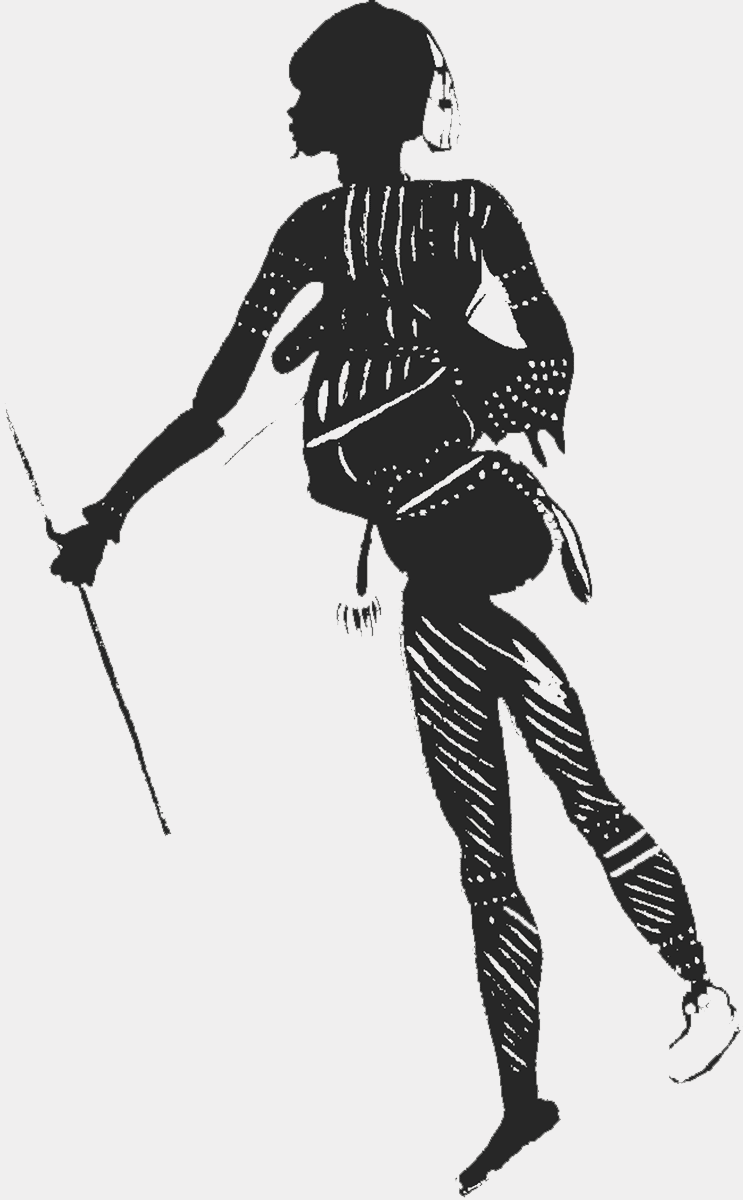

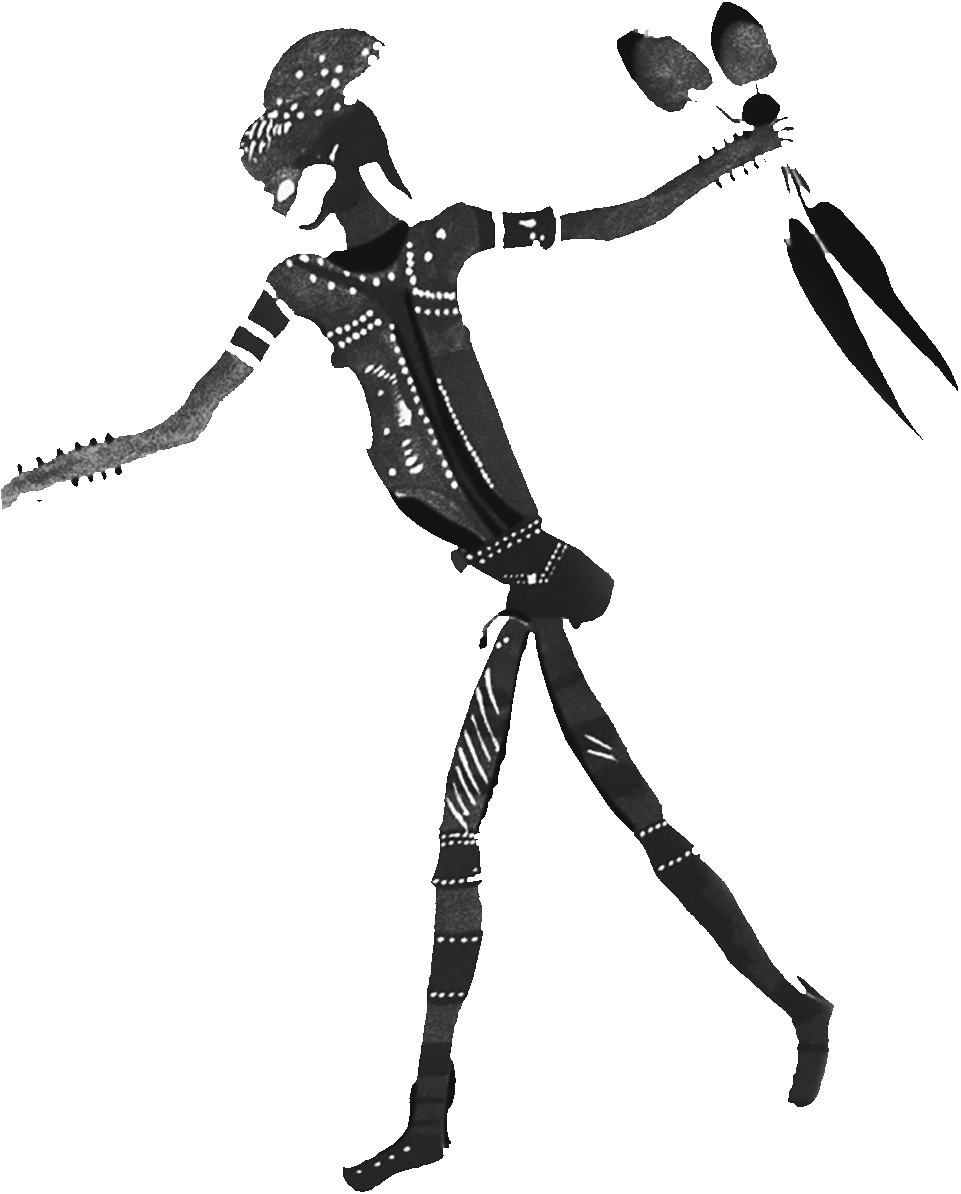

The 'White Lady' archaeological site is located a short distance from the Khorixas to Hentie's Bay road, in the area of Uis, on the Brandberg Massif - Namibia's highest mountain. It is now accepted to be a San - Bushman - painting, like the thousands other painted figures of the Brandberg. Damaraland (a name given to the north-central part of what later became Namibia, inhabited by the Damaras) is very rich in bushmen rock art sites, including, for example, Twyfelfontein. The 'White Lady Group' is in a cave known as the Maack Shelter, with more than 50 human figures, as well as oryxes, on a rock panel measuring about 5.5m x 1.5m. The White Lady figure itself measures roughly 39.5cm by 29cm. The site is located beside the (normally) dry Tsisab river. The white legs and arms of the figure suggest that part of the body was painted and that it was wearing decorative attachments on the legs and arms. The red and black paint was probably made using ochre, charcoal, manganese, hematite, with blood serum, egg white and casein (proteins found in mammalian milk) used as binding agents. The pigment in the white paint was clay.

A tracing of the White Lady and accompanying paintings by Harald Pager clearly shows 'her' to be a man, as indeed are all the other human figures in the group. If Harding's suggestion that they represent an Ovambo ritual is correct, they would have been painted after the Ovambo farmers entered Namibia within the last 2,000 years. It is also possible that they represent a hunter-gatherer ritual that was later adopted by the Ovambo. Whichever scenario is correct, the saga of the White Lady remains a fascinating example of how important it is to see rock art through knowledge of the beliefs of the people who made it, rather than through the eyes of a transient European visitor with no experience of local customs. We can also ponder on whether the 'White Lady' site would receive as many visitors as it does today if the Abbe Breuil had correctly identified 'her' as 'him'.

According to John Kinahan, most of the engravings at Twyfelfontein present the subject in broad, generalized outline. Animals are shown in profile, usually with both fore- and hind legs depicted. Another conspicuous aspect of the engravings is that they vary a great deal; some appear crude and unfinished, whilst others are highly worked and artistically accomplished. A particular feature of the rock art of Twyfelfontein is its integration with the surroundings. The artists deliberately placed their art at significant points on the terrain. Some are in cracks or fissures which served as entry points to the supernatural world. Some engravings - usually entoptic geometric patterns - are often associated with the 'edges' of rock faces. The edge is integral to the image, reflecting the trance and the edge of consciousness.

The rock art at Twyfelfontein [Afrikaans for 'uncertain spring'] was probably produced during the dry season, and around 5,000 years ago when the climate was even drier than at present, because the shortage of water and food forced people to congregate near the spring. This then became a time of intense ritual activity. Rituals helped to strengthen the values and cohesion of the group: they were performed during initiation into adulthood, to heal the sick, to ensure successful hunting, and to make rain. The ritual traditions represented in the rock art of Twyfelfontein saw their greatest flowering during the last 5,000 years; a period of increasing aridity during which hunter-gatherer communities developed and perfected a wide range of economic survival strategies.

The rock art was the preserve of the medicine people, or shamans, and had 2 functions: as a means to enter the supernatural world - the spirit world - and to record the shaman's experiences in that world. Each and every feature of an engraving is deliberate and holds a specific meaning. Sometimes the meaning is difficult to establish directly, but often an informed guess is possible. The 'Dancing Kudu' for example shows an obviously pregnant female. Kudu were valued as potent symbols of fertility and this may explain the choice of a kudu cow for the image. However, we cannot know all the multiple meanings that the images held for the artists and viewers.

Geometric symbols: the shaman's vision became disturbed at the start of the trance; the shaman would see patterned flashes of light. Produced in the brain, these flashes are also known as 'entoptic' images. They are depicted in the seemingly abstract geometric patterns in the rock art. Meanders, dots, lines, grids, spirals and whorls resemble entoptic or inner-eye images recorded in neurophysiological experiments. Although entoptic images are similar for all people in the world, the associations formed in a state of trance are contextual. The shaman fuses the hallucinatory visions with images of animals and other potent spiritual symbols. It is possible that making the engravings helped to prepare the shaman for a state of trance. The repetitive chipping at the rock and the monotonous sound could have contributed to mental concentration.

Lion Man: the 'Lion Man' engraving shows 5 toes on each paw - a lion only has 4 toes. The deliberate combination of human and animal features shows that this is a shaman who has transformed into a lion.

Hooves and feet: engravings of human footprints and animals may depict the moment of transformation from human to spirit animal. Sometimes the hoof prints of animals are shown with human footprints. On other occasions, the entire panel is devoted to the engraved spoor.

Birds: birds are prominent among the Twyfelfontein engravings, but do not include short-legged species that perch or hop. All the birds shown are species that stride, such as ostriches. The birds are often shown in a line, walking or dancing like people in the typical 'arms back' posture of ritual dance. Such images may represent people transformed into birds.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation