Andrew Skinner

Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

Sam Challis

Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

San forager populations in nineteenth century southern Africa were subject to some of the most destructive aspects of the colonial project, their communities displaced, destroyed and enslaved. Refugees from these populations formed raiding bands and engaged in prolonged armed insurgencies, and in this experience of pervasive, irregular conflict, became acutely vulnerable to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. PTSD dysregulates normal behaviour and cognition, notably comprising an individual’s ability to maintain normal social connections. These symptoms are readily intelligible to San forager epidemiologies, which already class disease as a social phenomenon. ‘Infection’ by antagonistic identities is prominent amongst causes of illness, disease itself manifesting as the expression of correspondingly anti-social or violent inclinations. In this idiom, PTSD is a disease for which ritual, visionary trance would be a conventional treatment—a disease which manifests its own visionary aspects, such as nightmares and flashbacks. Religiously inflected, neurologically-generated phenomena are an accepted avenue of interpretation of San rock art, and together with the symptoms of PTSD, we stand to access some of the affective, experiential histories embedded in rock art images of conflict.

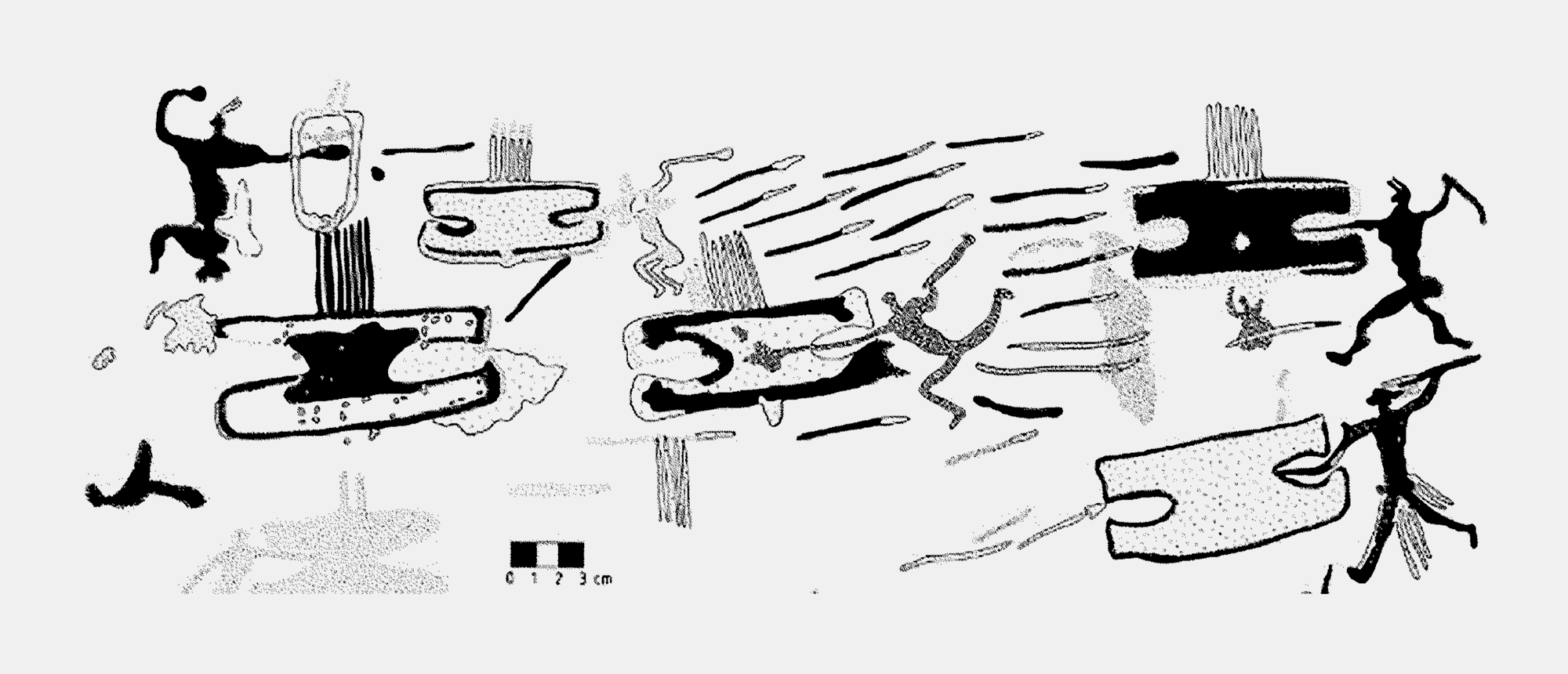

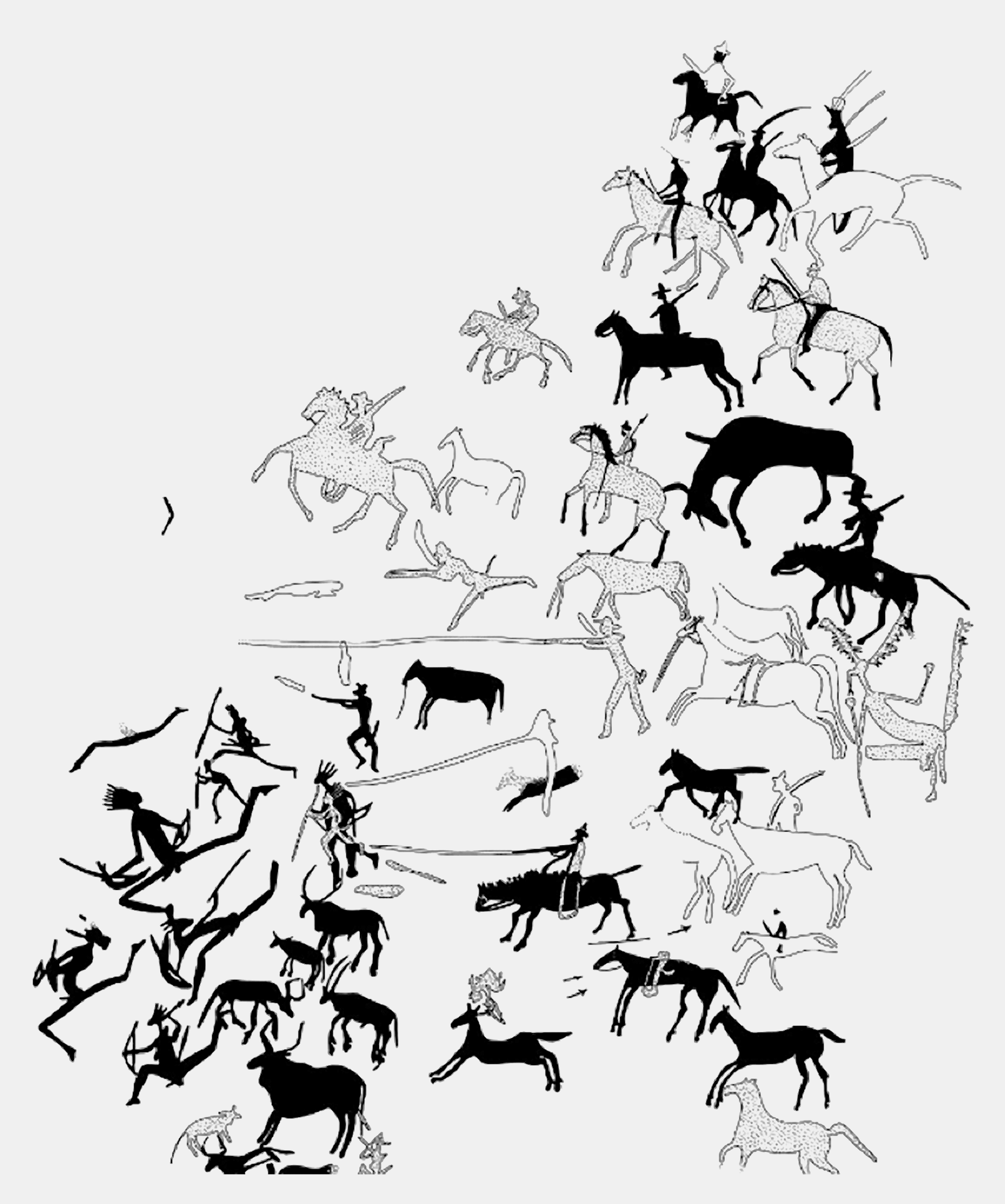

Images of mounted individuals, using guns and wearing wide-brimmed hats. Beersheba, Smithfield District, Free State, South Africa.

Accordingly, settlement efforts proceeded in tandem with forcible displacement, destruction and enslavement of forager societies who embodied this unruliness (Gordon & Douglas2000; Adhikari 2010; Sinclair Thomson & Challis 2020). Trade routes and exchange relationships that had connected indigenous societies for hundreds, if not thousands of years (e.g. Stewart et al. 2020; Fewlass et al. 2020), were broken and dispersed (Challis & Sinclair Thomson in press).

“‘Wholesale extermination’ does not exhaust the range of interactions that existed between hunter-gatherers and colonial agents” (McGranaghan 2012: 112), nor does a model of violence as exclusively that of coloniser upon colonised fully represent regional dynamics (King & Challis 2017; King 2019: 51; cf. Stein 2005: 23–28). However, these nineteenth century landscapes were very much in the process of being ‘locked down’, compartmentalised metaphorically and practically (Roche 2008; cf. Netz 2004), their indigenous populations forced under violent systems of control whose parameters were defined by ethnicity (Skinner 2021a). Colonial idiom connected concepts of security to the demarcation of southern Africa’s peoples (King 2018: 665), and in a foreshadowing of Apartheid, many of these societies were essentialised, consolidated and spatially constrained, while the environments upon which they had subsisted for generations were now tangled in barbed wire.

Images of mounted individuals, using guns and wearing wide-brimmed hats. Beersheba, Smithfield District, Free State, South Africa.

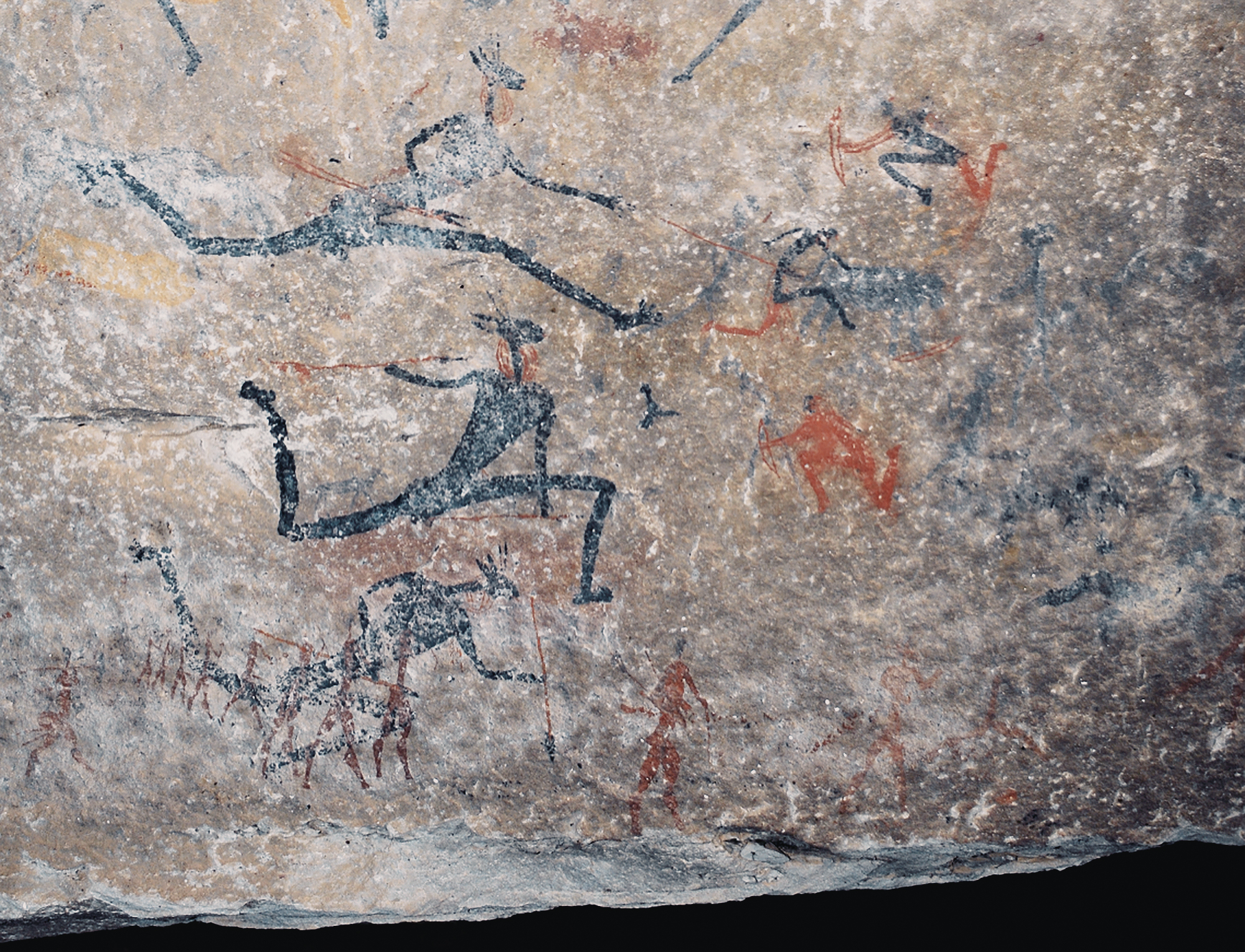

Irregular warfare generally destabilises the definition of ‘combatant’ beyond what it would describe in uniformed combat (Kiras 2019: 184), but as colonial authorities used ethnicity to classify their opponents, forager society was implicated en bloc with raiders, thus rationalising indiscriminate use of force. It suited the colonial project to cast forager populations as residuals of humanity’s primordial state (Gordon 1992), and alongside emerging ‘scientific’ formulations of race (Coombes 1994: 9), this meant that those who expressed forager identities and lifeways fell short of the ‘criteria of humanity’ (Hitchcock 2015: 263), excluding them from moral injunctions on violence and killing. Perhaps accordingly, painted forager rock arts of the time hint at an apocalypse underway (Ouzman & Loubser 2000), or at the least, an expanse of intensely destructive conflict across the subcontinent (Challis 2008), including between indigenous societies (figures 3, 4, 5).

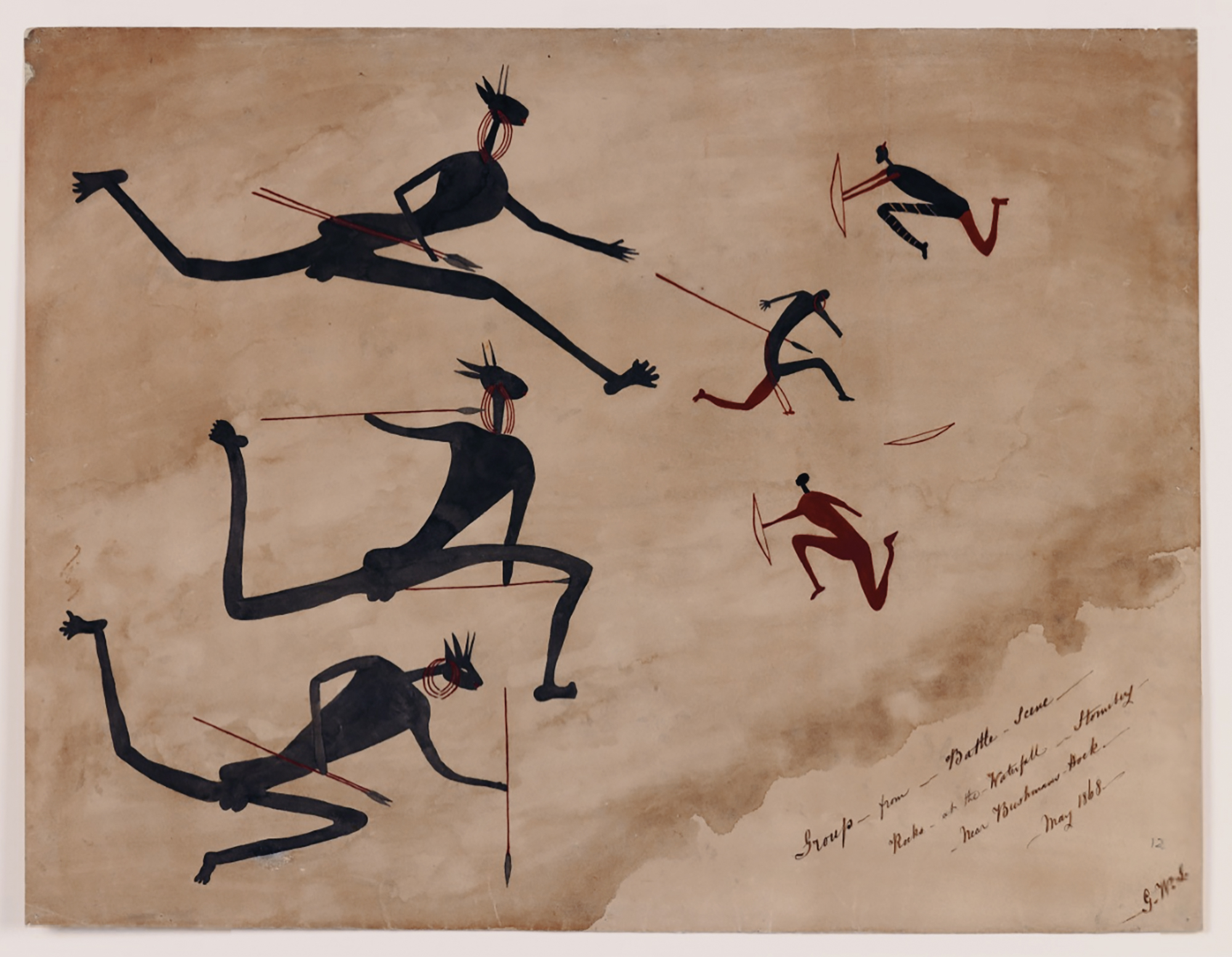

Conflict between spear and shield wielding individuals. Rouxville, Free State, South Africa.

Expanded detail of the panel at Beersheba. Although this has previously been represented as the colonial ‘slaughter’ of southern African hunter-gatherer populations, on closer inspection it depicts warfare between indigenous groups, one with horses and guns, the other with bows and arrows. This is signalled by the figure with the feathered headdress and horse’s tail on the centre-right, likely to have been a ‘war doctor’ (see Challis 2018, figure 5).

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a suite of behavioural and cognitive dysfunctions that manifest in the wake of a traumatic event—dysfunctions that would have been readily explained by forager theories of disease. In San ethnographies, disease has social parameters (McGranaghan 2012: 204, 450), with antisocial or violent conduct being the severest expression (Guenther 1999: 37). Symptoms of PTSD would notably compromise an individual’s social capabilities, spurring their community to turn to healing through ritual, visionary trance (e.g. Katz 1984; Lee & Marshall 1984: 103). Trance is an accepted catalyst for the art, although PTSD has its own visionary components – nightmares, flashbacks and re-experience – that are intrinsically linked to the traumatic event, and would likely have intruded on ritual altered states of consciousness, especially those intended to heal the corresponding social symptoms.

Informed interpretation has long rejected the art as an account of ‘daily life’, and this extends to images of conflict: what is depicted is rather a euphemism for spiritual warfare (Campbell 1986; cf. figures 6, 7 above). Nuance has developed in this understanding, particularly in art produced by raiding societies who enacted protective magics and unifying ideologies in paint (e.g. Challis 2014, 2018; Sinclair Thomson & Challis 2017). Additionally, the emotive qualities of conflict images – their ‘affective dimensions’ (after de Luna 2013) – “hold great promise for bringing much-needed subjectivity to central themes of early African history, making it “legible” to a broader audience, and for transforming how we understand the developments to which we already attach great explanatory power” (de Luna 2013: 125 in King 2019: 16; cf. Smith 2010).

The art is a material remnant of nonmaterial phenomena (Pagel & Broyles 2019: 197), yet it retains “sensuous properties” (King 2019: 16) that reflect the artists’ personal experiences and states of mind. This contribution examines the interface of belief and biology that emerges following a traumatic event, its likely course of diagnosis within indigenous epidemiologies, and its potential for unlocking contextual meanings in the conflict rock art of southern Africa.

PTSD develops in individuals who have been exposed to death, serious injury, sexual violence, or the threat of any of these to the self or others, an exposure first and aptly described in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (1980; hereafter DSM) as one “which lies [so] outside the normal pattern of human experience [that it] would clearly cause suffering in virtually everyone”. This results in psychiatric disturbances that cause “impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning” (APA 2022: 302–303).

PTSD has been extensively documented since the Vietnam War (Gersons & Carlier 1992; Marmar et al. 2015), although retrospectives of ‘shell shock’, ‘war neurosis’ and ‘neurasthenia’ (Macleod 2004; Loughran 2010; Fuehsko 2016) place recognition of a syndrome of prolonged, combat-instigated distress nearer the First World War (e.g. Myers 1916; Royal Army Medical Corps 1922; Phillips 1979). In the medical fraternities of Victorian and Edwardian England, however, the paradigm of ‘civilised morality’ governed both diagnosis and treatment of post-traumatic stress (Hale 1971). “The physician’s attitude toward the hysteric and the neurasthenic was … one of moral condemnation: [patients] were seen as morally depraved, wilful and egoistic” (Bogacz 1989: 231). Moral fibre was a defining feature of civilised humanity, and one from which courage and character descended. Thus, “fortitude in war [had] its roots in morality,” while the emerging understanding of ‘shell-shock’ was met with the contention that the label served only to “[give] fear a respectable name” (Bogacz 1989: 231). Later research would establish extensive physiological (Yehuda 2002: 110-112; Yehuda et al. 2015) and evolutionary dimensions of the disorder (Zefferman & Mathew 2021), particularly as part of a range of largely universal neuropsychological responses to extreme stress. Accordingly, the earlier perspective no longer holds.

The aggressors, in this case, are therianthropes, indicated by their partially animal features. This is a common euphemism for bodily transformation that is experienced during altered states of consciousness, lending the images a spiritual/religious quality.

The Vietnam War, for example, has always occupied a contentious position in American society, and this low or mixed moral status has compounded adverse outcomes in combat veterans of the conflict. Asian-American Vietnam veterans suffered more intense manifestations, as racial stigma from their fellow GIs further degraded the value of their experiences (Loo 1994: 651). By contrast, Turkana raiders in Kenya incorporate community members in rituals which communally recognise the practicalities of killing during raids, mitigating some of the corresponding psychological injury (Zefferman & Mathew 2021: 7).

The “social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations, that is, moral injury” (Litz et al. 2009: 697), has a demonstrable connection to the onset and progression of PTSD (Yehuda et al. 1992; Fontana et al. 1992). Particularly injurious are events that clash with an individual’s fundamental assumptions, such as the belief that the world is generally benevolent or meaningful, that the self has value, or that a social contract holds (Litz et al. 2009: 698–699).

There is also a particular vulnerability of refugees to the onset of PTSD (Fazel et al. 2005) which may be up to ten times greater than populations into which they subsequently resettle (Crumlish et al. 2010: 237), even accounting for wider patterns of resilience (Sack et al. 1997). The nature of the refugee experience increases risk as a factor of refugees’ displacement by conflict, the fracturing of their social institutions, and their liminal political, ethnic and economic positions (George 2010).

As a population uprooted by colonial aggression, and affected by violence that did not discriminate between combatants and civilians, San forager populations would have been acutely vulnerable to PTSD. In cases where these societies mobilised resistance, conflict would take the form of intense, horseborne gunpowder raids; not pitched-battles, but guerilla incursions and counter-incursions against occupying forces. There would be few, if any, prisoners taken, and horrific injury and death would be common.

It is reasonable to think that these societies would have had significant incidences of PTSD, although caution is warranted when applying any therapeutic apparatus universally. As with any psychological disorder, PTSD is “the product not of trauma in itself but of trauma and culture acting together” (Bracken 2001: 742; Kienzler 2008: 223). Conversely, it is also not a matter of classing it as a disease exclusively of western sensibilities. Some symptoms can be reproduced in animal models (Kohda et al. 2007), and among human case-studies there is a relative invariance of the symptoms that evoke defensive behaviours, suggestive of their evolutionary significance. Zefferman and Mathew (2021) found a bifurcation of responses, with uniform manifestation of avoidance behaviours and hypervigilance, while depressive symptoms more closely followed moral (and thus cultural) principles. While PTSD is not innately culturally-specific (Yehuda et al. 2015), affected communities and individuals process trauma according to their social context. Inasmuch as culture determines the moral injuriousness of an event, it thus impacts the range, expression and intensity of symptoms.

The question can also be seen as one of detection and presentation of symptoms rather than one of their occurrence. Language used to describe symptom and trauma will differ, highlighting the importance of building an ethnographic model to understand specific cultural responses (Manson 1997), and establishing the relevant ‘idioms of distress’ (Kaiser et al. 2015) with which to understand them.

In the therapeutic context, symptoms of PTSD class into four categories (table 1). Intrusion, the unexpected/undesirable re-experience of a traumatic event; avoidance, the compulsion to avoid references or recollections of the event; cognition, the impairment or interruption of cognitive capacities and mood; arousal, the impairment, interruption or irregular manifestation of wakefulness or reactivity.

| Table 1 | |||

| Symptoms and diagnostic criteria of PTSD described in the DSM-V-TR (APA 2022: 302–304) | |||

| Categories | |||

| Intrusion | |||

| Memories, Nightmares, Flashbacks, Re-experience, Physiological distress | |||

| Avoidance | |||

| Representational, Symbolic | |||

| Cognition | |||

| Amnesia, Dysphoria, Persistent Negative Beliefs, Persistent Negative Mood, Detachment/Estrangement, Lack of Affect | |||

| Arousal | |||

| Irritability, Aggression, Recklessness, Hypervigilance, Exaggerated Startle Response, Low Concentration, Sleep Disturbance |

These symptoms vary in the extents to which they are culturally- or biologically-determined (as above), and in recognition of this, discussion below proceeds from defensive patterns to depressive ones, more invariant symptoms to more culturally-mediated ones.

Avoidance is the first, and perhaps the simplest manifestation of defensive behaviour, being the symptoms that compel an individual to avoid stimuli that evoke or resemble features of the traumatic event. In this, it would act to intimately connect cause to effect. As other symptoms manifest, and PTSD begins to closely resemble a core definition of ‘disease’ in San epidemiologies, the root cause of that disease would be discernible in an affected individual’s compulsive avoidance of references to the traumatic event.

This, in turn, provides a lens through which forager societies assess traumatic events for their impact on the individual; with the traumatic stressor likely being violent in nature, assessment of PTSD symptoms runs parallel to assessments of violence. In San models of propriety, violent conduct is generally deplored – it has low moral status – and thus the culturally-mediated disruptions of cognition and arousal are more likely to impactfully manifest. We discuss these depressive classes of symptoms in tandem, reflecting their marked social intrusiveness. A social lens would preoccupy the forager perspective in any case, but these symptoms are notable for their disruption of an individual’s ability to maintain interpersonal relations, which are defining characteristics of disease in forager idioms.

As these symptoms would indicate a disease, the normal course of disease treatment would follow. Visionary trance is a known mode of treatment for injury, as well as disease in the bacteriological sense, among San foragers (Lewis-Williams 1992: 56–57). PTSD behaves as a disease, but ironically resembles its treatment as well. Intrusion manifests as nightmares, as well as visionary, psychological and somatic re-experiences of the traumatic event. Dreams and nightmares are directly compared to volitional trance in San ethnographies (e.g. Katz 1982: 218-219; Lewis-Williams 1987), although those manifesting as symptoms of PTSD may be notably more intrusive and subjectively ‘real’ than in the normal course of dreaming (Woodward et al. 2000). Trance would evoke yet more re-experience, as neurologically-generated imagery tends to ‘leak’ into the conscious perceptual frame during hallucinatory events (Diederich et al. 2015: 295–296). The already intrusive patterns of PTSD would impose themselves ‘in plain view’ during rituals meant to resolve them, further cementing violent event and social disorder as catalyst and disease respectively.

In forager idioms, disease is brought about by antagonistic forces, such as ‘sorcerers’, and animals with antisocial inclinations, such as lions (McGranaghan 2012: 204, 2014a: 14). The root cause may be abstract, however, as a failure to maintain obligations, or to express ‘correct behaviour’ on the landscape, is what brings these encounters about (McGranaghan & Challis 2016). Violence is a practical disruption of social norms, and by the nature of avoidance behaviours, we see emerging symptoms connected to a specific violation.

The DSM defines avoidance along two lines (see criteria C; APA 2022: 303), compulsive avoidance of memories, thoughts or feelings about an event, and effort to avoid cues that evoke those memories, thoughts or feelings. In everyday social settings, references to traumatic events would be very difficult to avoid.

Foremost amongst the symbolic media of San social life is storytelling. Communal narrative is a vital element of daily experience (see Guenther 1999; Wessels 2010), being highly performative and interactive with its audience, employing a style that often plays to ‘traditional’ narrative stereotypes, while also selectively integrating folklore and personal biography (McGranaghan 2012: 17–18; Guenther 2020: 215–217 cf. Lewis-Williams 2015).

It further acts as commentary; this form of “‘talking’ is not just oral discourse, but is instead rhetorical discourse” used for its “capacity to influence the attitudes and opinions of others” (Guenther 2006: 243). It capitalises on the general ambiguities of San folklore – the uncertain frames of past and present, ‘real’ and mythic – to blend a given moment with wider cosmology, or interpret those wider patterns through the lens of the here and now. As a pragmatic institution, stories can exemplify ‘correct’ social norms (see ‘Great Stories’ in McGranaghan 2012: 178–179), although retellings remain fluid, able to be inflected to selectively highlight certain aspects of social canon (Hewitt 1986: 235-246; Wessels 2007). In this way, they may act as instruction, correction, and sanction of others, or as ‘levelling’ of oneself to preserve appropriate humility after a notable success (Guenther 2006: 245).

The retelling of a violent event would be an expected mode of making sense of it, and managing its consequences for both individual and collective. Framing the traumatic event within the patterns that have characterised the universe for the longue duree opens it to known interventions: in the ways that violence has been resolved in the past, near and mythic, so too may it be resolved in the present. Conversely, a retelling that contrasts the event against stories which would normally be instructive of proper behaviour would be to ‘set straight’ implicated individuals. In either event, violent events and conduct would emerge into the social/discursive frame of daily life, their problematic consequences rehearsed, debated and hopefully ameliorated.

Problematic behaviours are embodied in the stereotype of the ‘different person’; one who is defined by anger and “inappropriately directed or unregulated violence [...] antithetical to |Xam [San] notions of propriety” (McGranaghan 2014b: 678). Anger is a defining characteristic of antagonistic animal identities – of predators, or ‘beasts of prey’ – and especially so when it rises to the level of doing physical harm. By taking-on the attitudes of beastly creatures, and in so doing, taking-in their problematic personal properties (McGranaghan 2014a, b; Challis and Skinner 2021), one others themselves from the social ordering of their community, becoming different. Different communities – communities of others – are idiomatically associated with violence, appearing as primordial antagonists in mythic narratives (e.g. McGranaghan 2014b: 678–679; Skinner 2017: 67–69), stereotyped as examples of failed or inappropriate socialisation.

Particularly distant, different communities are also the idiomatic source of disease, characterised by their firing of arrows into the air that rain down upon others, and it is the strikes of these invisible arrows that transmit various maladies (McGranaghan 2012: 222–223; Skinner 2017: 82). Indeed, it is a defining aspect of a ‘stranger’ to “shoot at people” (McGranaghan 2014b: 678), illustrating the relationship between this behavioural ‘difference’ and disease. Arrows are a medium through which communities enact violence upon one another (see figures 8, 9, 10, 11), and thus following the wider equivalence, act as the media for the transmission of disease.

(Above) FIGURE 8 & 9 Images of conflict with widespread use of arrows and thrown spears, the media of transmission of violent energies, mirroring the transmission of disease. Wepener, Free State, South Africa. FIGURE 10 & 11 More extensive imagery of arrows. Rouxville, Free State, South Africa. FIGURE 12 Detail of bleeding, wounded individuals. Rouxville, Free State, South Africa. FIGURE 13 Detail of an individual undergoing significant somatic distortions. Underberg, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa.

On return from a violent event, it is reasonable to expect one to be ‘sick’, according with the infectious nature of violent conduct, the illness-inducing properties of violent material culture, and the literally and idiomatically hazardous behaviours of communities defined by violence. Giving in to violent conduct oneself would be to have been ‘infected’ with problematic inclinations and identities of different persons (see |gwaiҙn, v. “to get into the flesh, take possession of”; Bleek 1956: 285; McGranaghan 2015: 276–277; Skinner 2017: 159). The symptoms of avoidance are merely coherent with this existing theory of disease, though just as much, they offer a tangible connection between a disease and its causal event.

Avoidance compels one to avoid direct references to an event, or to moments that evoke or recollect it; it makes one ‘fightful’ around the narrative events that are the social pulse of forager society, or ‘skittish’, as a wild animal is when incorrectly approached (McGranaghan & Challis 2016: 586; see Skinner & Challis 2022). While it is difficult to overstate the centrality of storytelling to the regulation and structuring of social life (Guenther 2006), there is equally profound significance in avoiding it, especially should a story’s intent be to ameliorate the consequences of an infectious event. Traumatic or violent events, especially those that would reach a clinical threshold sufficient to induce PTSD, would certainly find themselves discussed in these public fora, symbolically and practically re-imposing themselves on the affected individuals. Avoidance, in turn, would make it likely that affected individuals would, either unintentionally or through compulsive behaviour, make some public demonstration of the connection between that event and their troubled states of mind.

This event would already have epidemiological implications, but the communal nature of forager social life engenders a strong injunction on violence, and confers on violent conduct a low moral status. This low moral status makes subsequent manifestation of depressive symptoms both more certain and more expansive, continuing a disease progression that is thoroughly comprehensible to San epidemiologies.

Disturbances of cognition and arousal overlap significantly, and would likely constitute a feedback-loop of social withdrawal, deepening negative mood, and behavioural dysregulation. These symptom expressions would then draw the original, traumatic event back into focus in the social/dialectic frame, further confronting the affected individual, and driving avoidance, estrangement and behavioural disruptions.

Cognitive disturbances (see criteria D; APA 2022: 303) abstractly resemble avoidance, manifesting as an inability to remember significant aspects of the traumatic event. Perhaps accordingly, this may result in a distorted perception of cause, effect and responsibility, leading an individual to blame themselves or others for what has happened. PTSD is sometimes characterised by event centrality: the traumatic event becomes a defining aspect of how an individual understands themselves and the world (Berntsen & Rubin 2007), implying that social compacts have been irreparably broken, and that safety and trust are now an illusion. One’s mood is correspondingly altered; positive emotions move out of reach, while negative emotional states such as anger, fear and guilt all greatly deepen. This manifests behaviourally as estrangement from others, detachment or loss of interest in socially-significant events. This withdrawal is a widely cross-cultural idiom of distress: “thinking too much” (Kaiser et al. 2015: 173–174).

San ethnographies describe this as “thoughts going astray” (LL.V.23.5871), or being ‘closed off’ (“His … thinking channels … were those that were closed”; LL.II.30.2754). This robs an individual of their ability to correctly regulate their behaviour, potentially even leading to a desire to cause harm (McGranaghan 2012: 174), building on the contiguity between assessments of violent conduct and alterity. On one end of this spectrum is the ‘man which different’ (LL.II.14.1317), following the model of ‘difference’ above, who is characterised by inability or disinterest in maintaining bonds with his family, or meeting his social obligations to the wider society. On the distant end – the bounds of violent predators – we see identities defined by a fundamental inability to understand, and correspondingly ingrained violent tendencies. There is a wider principle that persons “‘possessed of their thinking-strings’ … would not engage in violent behaviours”, while it is the definition of a monster to fail to “behave according to normative pressures [and instead] embodying that which cannot be permitted” by sociable persons (McGranaghan 2014a: 6, 10).

Avoiding references to a violent event, or struggling to remember its defining details, would manifest most in the moments of communal sense-making that San storytelling represents. Displaying a lack of trust in others, or failing to live up to others’, usually reciprocal, trust and obligations would be quickly and persistently highlighted in communal situations. A likely assessment would be that one had lost the ‘understanding’ that once characterised them—that they had lost their thinking-strings.

This could be met by ‘forced eavesdropping’ (Silberbauer 1982: 26–27): open gossip, intended to gently sanction the one being spoken about, consciously within earshot. As social failures accumulate, greater degrees of censure would follow, culminating in open ridicule (Guenther 2006: 245–246). “Talk hurts” (Wiessner 2005: 121), furthering the existing compulsive avoidance or withdrawal from the normal flows of social life, deepening the “ongoing disruption of social relationships and typical channels of reconciliation” that might otherwise potentially resolve the corresponding moral injury (Kaiser et al. 2015: 176). Affected persons “‘cannot resume the normal course of their [lives]’ because these symptoms disrupt the fundamental interior narratives which [individuals] continually construct for, and about, themselves and their world. Traumatic experience produces narrative structures that are fractured and erratic … which will not sustain integrated notions of self, society, culture or world” (Robinett 2008: 297). This is particularly troublesome not because the traumatic event has poor integration into an individual’s worldview, but paradoxically, because the event becomes integral to it (Berntsen & Rubin 2007).

Interruptions of arousal and reactivity (criteria E; APA 2022: 303) would simply conform to this existing connection of violence and some fundamental flaw of identity, character and social ability. Dysregulation of arousal produces exaggerated vigilance and startle responses, and disturbances of sleep and concentration. Insomnia is an established comorbidity, cause and diagnostic symptom of many mood disorders (Peterson & Benca 2006), occurring at a nexus of neuropsychological systems that would certainly intensify the manifestation of other symptoms, such as the disruptions of mood discussed above.

Hypervigilance and startle responses have a particular place in San notions of propriety. As with much other forager idiom, hunting is a central rhetorical tool and euphemism for many aspects of society and cosmos (Biesele 1993). The skittishness of an antelope – its being difficult to hunt on account of its nervousness (McGranaghan & Challis 2016: 586) – indicates a negative social disposition (Challis & Skinner 2021; Skinner & Challis 2022). A skittish thing is ‘fright-ful’, ‘spoiled’, ‘wild’ and likely aggressive, the implications best seen in the contrast with “notions of ‘stillness’ [which were] opposed not only to movement, but also to violence: the antithesis of the patient, still man was someone who became ‘quickly angry’” (McGranaghan & Challis 2016: 586).

It is appropriate that this predicts the balance of symptoms in this category: irritability, unprovoked and violent outbursts, and reckless or self-destructive behaviour. Avoidance ties a specific violent event to the manifestation of symptoms, while cognitive interruptions compromise the individual’s will and ability to engage in the social institutions that might otherwise offer a resolution. Arousal presents a particularly confrontational aspect of this socio-neurological disease, and clearly resolves it as such in San epidemiologies.

Behavioural dysregulation, particularly that which rises to the level of violent outbursts, is something to which San social institutions are highly sensitive. The idiomatic framework recognises that among the chief causes of disease, and violent conduct, is the infection of the individual with the problematic identities of antagonistic others (McGranaghan 2015: 277). One who becomes ‘quick to anger’ is one who both behaviourally resembles a lion (McGranaghan 2014a: 13), and who acts out the defining characteristics of lions as a category of persons (Challis & Skinner 2021). Lions, in turn, are premier among the categories of ‘wild’, aggressive and antisocial stereotypes. To be quick to anger, poor of temperament and sensitive to slights is to be as lions characteristically are (McGranaghan 2014a: 10), and thus to enact their identity.

To be ‘always on edge’ or ‘tightly wound’ in this way is highly intelligible to San epidemiologies, and is part of what makes the progression of PTSD that of a disease. It conforms to the basis of cause (as a matter of ‘infection by identity’), transmission (through violent means and material culture), and symptom (antisocial or violent conduct). It is also possessed of a somewhat “contradictory structure that is once chaotic and fathomable” (Robinett 2007: 296), as an individual’s role in normal social life becomes fragmented, difficult and disruptive. Concern for them as a friend or family member comes alongside concern for the collective, both individual and community likely struggling with the same psychological and moral injuries. However, just as the surrounding idioms possess much insight into this disease, they already have mechanisms in place to achieve treatment and social rehabilitation—in the form of ritual trance. PTSD maps readily onto San epidemiologies, and so too the visionary experience of an altered state of consciousness, ritually employed to heal disease, significantly resembles the symptoms of intrusion.

San ritual trance dances are a central element of both social organisation and cosmological contextualisation (Katz 1982; Biesele 1993: 70–74; Guenther 1999: 81; Lewis-Williams 1992). Using hyperventilation and repetitive physical exertion, shamans induce in themselves altered states of consciousness. A community facing sickness or notable social disruption may embark upon a trance experience in which several shamans attain this visionary state together, and act therein to ritually defeat the antagonistic agencies whose identities have contaminated the affected individuals. By ‘snoring’ or ‘sucking’ away the sickness during a trance, a healer is thought to produce miniature arrows or even lions, emblematic of the illness-causing entities they have removed (Low 2007: S84).

What is seen in these altered states is highly responsive to collective input and psyche. Altered states of consciousness present artefacts of optical and neurological systems to the conscious frame (Diederich et al. 2015: 295–296). These imageries, and accompanying somatic hallucinations, are granted significance by their appearance in a religious context (Froese et al. 2013: 208), construed according to a combined narrative environment of cosmology (Lewis-Williams & Dowson 1988) and community sense-making processes in an intimate yet public sphere (cf. Torrance & Froese 2011). In this way, it closely resembles the storytelling practices that are similarly used to make sense of the larger cosmos in terms of smaller biographical events, and vice-versa (Guenther 2006: 248).

PTSD is a disease in San epidemiologies, and qualifies for treatment through ritual trance. Simultaneously, we can expect a trance undertaken to resolve the progression of PTSD to be highly charged by the same event that imposes its signature on the symptoms being treated. Cosmology connects the violent event to the emerging disease in an almost deterministic way. Accordingly, when trance is undertaken to heal this disease, the expectation would be for that causal relationship to be discernible; altered states experiences would mingle with cues, symbols, narrative representations, memories and feelings associated with the traumatic event—the root cause.

There is a further phenomenological connection between trance and PTSD. Symptoms of intrusion (criteria B; APA 2022: 302–303) closely resemble significant visionary experiences of this religious framework. Intrusion manifests in intense psychological distress when re-exposed to cues that symbolise or represent the traumatic event, and uncontrollable physiological reactions that mimic the fear-responses that arose during the event itself. True to the name, it also includes intrusive and distressing memories, dreams, and moments in which an individual feels the event to be reoccurring. At its most extreme, this may be dissociative to the point that one cannot distinguish between symptom and reality.

In a visionary religion, visionary symptoms have pronounced significance. Dreams and nightmares have direct ethnographic equivalence to trance (Lewis-Williams 1987). One may do in dreams what one otherwise does in trance (e.g. LL.II.6.625). Just as much, dreams are thought to be conveyances of important – if ambiguously-framed – cosmological information (McGranaghan 2012: 198). Nightmares are an oft-violent expression of this (Bleek 1935: 26–27; Katz 1982: 218–219), conveying dangerous or fatal occurences to come (LL.V.15.5110–5111, 5131–5140; “thy head’s scars” in LL.II.9.978–985). PTSD-instigated nightmares would make repeated intrusions, conferring the violent event a higher significance on account of this resemblance to trance and other known channels of cosmological information.

Somatoform dissociation (Hart et al. 2000) is another intrusive symptom, manifesting as a loss of normal bodily sensation, and a dysregulation or disordering of sensory inputs. This is a waking phenomenon, unlike dreams and nightmares, yet it draws another parallel to the dissociative and somatic aspects of trance experience. “All of the senses, not just the visual, hallucinate” in trance (Blundell 1998: 5), neurological feedbacks generating sensations of travelling underwater or underground, of flying into the sky, or of being stretched or distorted beyond normal physiological limits (Lewis-Williams 1986: 173–176; figures 13, 14).

Dissociative flashbacks, another characteristic of PTSD, further resemble the experience of altered states of consciousness. They impart “strong sensory impressions, and the sense of ‘nowness’ or of the event occurring in the present”, with intensities ranging from intrusive recollections to periods in which an individual loses all contact with their surroundings (Brewin 2015: 1–2). This phenomenologically parallels dissociative altered state experiences, and given the religious expectations for trance, would potentially present their contents in a cosmological frame, presenting a tableau of violent acts in the same format that one conventionally accesses information about the universe.

Simultaneously, visionary experience in trance offers a mixture of narrative sense-making and communal care for the individual, following a broad societal recognition of synergies between individual and collective social health. Additionally, visionary experience itself appears somewhat unique in its ability to shape treatment and recovery (although this remains a developing subject; Krediet et al. 2020). The contemporary route of psychedelic treatment is pharmacological rather than ritual-physiological, as that induced in trance, but there is reason to treat these experiences as broadly equivalent (Froese et al. 2016; pace Helvenston & Bahn 2006). In any event, the neurological mechanics may not be as important as the visionary element; it is the subjective experience of an altered state that seems largely to account for its therapeutic potential (Yaden & Griffiths 2021).

For our purposes, the contextualising effect of trance is one that connects universal mechanisms to singular human experience. Even a disjointed remembering of a violent event can be well-ordered by its presentations in ritual contexts that are already a primary means of collective sense-making. On one hand, trauma sufficient to catalyse PTSD is such that it rises to a “‘speechless terror . . . [an] experience [that] cannot be organised on a linguistic level’ and thus becomes not only inaccessible but also unrepresentable” (Robinett 2007: 290). On the other hand, visionary altered states of consciousness provide a literal superimposition of belief and personal experience, permitting an initially nonlinguistic and intuitive understanding to be reached in a communal, supportive setting. Then by collectively ‘narrativising’ the traumatic event – forcing this otherwise broken state of affairs to ‘fit’ a grander narrative – a more semantic sense can be made of it.

The social imposition of PTSD symptoms would set in motion a ritual response—altered states of consciousness undertaken with the expectation of defeating antagonistic influences. Alongside neurologically-generated reflections of the originating traumatic event, this acts to bring violent imagery into focus during trance. Trance, in turn, evokes these violent schematics in a ritual-religious context, conferring on them a cosmological context that can serve to organise even an otherwise fragmented worldview.

This is where PTSD shows its potential as an interpretive tool. Trance looms large in the interpretation of southern African San rock art, with the images posed as part reference to, part representation of, ritual altered states. In San epidemiologies, PTSD is a disease requiring just such a ritual intervention, while bearing its own parallels to religious experiences. The neurological intrusions of PTSD, or the associative intrusions of the traumatic event, would appear in the course of ritual altered states—in particular, reflections of ‘real’, violent events would manifest in art just as they neurologically, visually and semantically manifest in the ritual-religious context of San ethnomedical practice. After all, highly charged, emotional events are one of the cornerstones of hallucinatory experience theory (Siegel & Jarvik I975: 111; Siegel 1977: 136 in Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988: 204).

Many forager societies who raised arms to resist settler colonialism survive only as “fleeting references in the … catalogue of annoyances” quashed in the nineteenth century (Challis 2012: 266). Much is being done to remedy this and other representational shortcomings (Skinner 2021b: 238–239), recognising the many sources and source-media that still offer depth and nuance to our understanding of the indigenous perspective of this period otherwise dominated by the colonial account. The rock art of the subcontinent is one such indigenous archive, although it needs new tools to unlock the meanings beyond those already isolated from the forms of San religious life.

Forager societies have long been sociopolitically marginal, and this rendered them vulnerable to trauma. Yet, it is this same vulnerability that opens rock art images of conflict to an understanding underpinned by historic moment and individual experience, alongside the visionary ritual activities already fundamental to interpretation. Even in a model primarily concerned with neurotheological and -psychological outcomes, there are many worldly eventualities that would intrude.

PTSD is prevalent in refugee communities, and populations involved in irregular or insurgent conflicts. San foragers saw themselves targeted by an ideological apparatus that justified not only slavery and genocide, but that extended combattant status across an entire ethnicity. They would certainly have been vulnerable to PTSD, although the corresponding symptoms were readily intelligible to their theories of disease.

In avoidance, San cultural intuitions about the disease-causing potential of violence are confirmed. The affected individual avoids talking about a traumatic event, and any symbolic references to it. In so doing, they demonstrate a causal connection between their emerging social disorder and the originating event, and undermine the normal course of public, narrative sense-making that is central to forager lifeways. A violent event is socially and existentially compromising, yet if an affected individual cannot or will not participate in mitigation of its consequences, then San epidemiology would recognise this as disease.

Depressive symptoms are more likely where an event is morally injurious, and given that violent conduct is negatively assessed in this cultural context, they are correspondingly more likely to arise. In its disruptions of cognition and arousal, PTSD presents exactly the kind of disease forager idioms anticipate—one of demeanour, compromising communal interdependence. An individual will struggle to sleep, struggle to concentrate, and dysfunctionally apportion blame for the event and its consequences. They will lose trust, perceiving the social order to have been irreparably broken, while dark, ruminating moods come to dominate their state of mind.

‘Closed off thoughts’ has direct ethnographic parallels with the more cross-cultural phenomenon of ‘thinking too much’, a behaviour that estranges an individual from their neighbours, friends and family. One will instead resemble the ‘angry’ and ‘different’ agencies of the landscape – such as lions – who are cultural stereotypes of inappropriately regulated or directed violence, and are often the idiomatic source of disease. Scattered and skittish, aggressive and hypervigilant, they will be much like monsters who fire arrows of sickness at human communities. Through outbursts and inexplicable anger, they will confront their community with clear markers of a disease in need of treatment.

Throughout, they will likely experience intrusions of the originating violent event. Nightmares are a diagnostic criterion of PTSD, but also a phenomenon ethnographically equivalent to trance. They intrude alongside waking flashbacks, and other, psychosomatic reflections of the violent event. As with other symptoms, these experiences have clear significance in San epidemiologies; violent exposure has resulted in a malevolent influence literally and figuratively ‘getting under their skin’, changing who and what they are into something monstrous, incapable of normal human relations.

In this context, ritual trance is the conventional avenue of treatment for disease, and an opportunity to expunge malevolent influences. In the narrative context of treating a disease brought about through violence, hallucinatory imagery in trance, and neurologically-generated phenomena brought about by the intrusive symptoms of PTSD, would be construed in a violent guise to match the expected cause of disease. ‘Real’ events and narratives would thus notably intrude on the ritual experience; violent imagery a foreground to a cosmological background already well-equipped to explain it.

Accordingly, we are obliged to remain vigilant to what a rejection of ‘real’ narrative implies in interpretation. Matthias Guenther asks (2020: 258) if there can be such a thing as “prosaic hunting” in a universe whose social and cosmological dimensions are closely entwined, and where numinous occurrences are to be expected even in the course of the most mundane traversals (Challis & Skinner 2021). We ask similarly if there can be a wholly ‘religious’ trance, when altered states emerge at the intersection of personal experience, biography and narrative. The “‘spirit world’ had relevance precisely because it manifested in day-to-day life” (McGranaghan 2012: 202), although just as much, the ‘real world’ has relevance because it manifests in trance, and forms the basis of its symbolic repertoire. This may be more than the ‘mundane’ world viewed through the lens of ontology, cosmology, and the phenomenologically distinct experience of an altered state of consciousness, yet even the most abstractly ritual explanation should in many ways struggle to escape the intrusion of historic narrative. Looking to images of conflict then, we should expect not only the real, and not only the apparently religious or neurological, but the combined moment and mind-state of someone experiencing something that was in dire need of making sense.

Adhikari, M. 2010. Anatomy of a South African Genocide: The Extermination of the Cape San Peoples. Cape Town: UCT Press.

American Psychiatric Association. 2022. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, text revision (DSM-V-TR). Arlington: APA.

Arndt, J.S. 2010. Treacherous savages & merciless barbarians: knowledge, discourse, and violence during the Cape Frontier Wars, 1834-1853. The Journal of Military History, 74(3): 709–735.

Berntsen, D. & Rubin, D.C. 2007. When a trauma becomes a key to identity: enhanced integration of trauma memories predicts Posttraumatic Stress Disorder symptoms. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21: 417–431. DOI: 10.1002/acp.1290

Biesele, M. 1993. Women like meat: the folklore and foraging ideology of the Kalahari Ju|’hoan. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Bleek, D.F. 1935. Customs and beliefs of the ǀXam Bushmen, 7: Sorcerors. Bantu Studies, 9(1): 1-47.

Bleek, D.F. 1956. A Bushman dictionary. New Haven: American Oriental Society.

Blundell, G. 1998. On neuropsychology in southern African rock art research. Anthropology of Consciousness, 9(1): 3-12.

Bogacz, T. 1989. War neurosis and cultural change in England, 1914-22: the work of the War Office Committee of Enquiry into ‘Shell-Shock’. Journal of Contemporary History, 24(2): 227–256.

Bracken, P.J. 2001. Post-modernity and post-traumatic stress disorder. Social Science and Medicine, 53: 733–743.

Brewin, C.R. 2015. Re-experiencing traumatic events in PTSD: new avenues in research on intrusive memories and flashbacks. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1): 1–5. DOI: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.27180

Campbell, C. 1986. Images of war: a problem in San rock art research. World archaeology, 18(2): 255–268.

Campbell, R.L. & Germain, A. 2016. Nightmares and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Current Sleep Medicine Reports, 2: 74–80. DOI: 10.1007/s40675-016-0037-0

Challis, S. 2008. The impact of the horse on the AmaTola ‘Bushmen’: new identity in the Maloti-Drakensberg mountains of southern Africa. DPhil dissertation, University of Oxford.

Challis, S. 2014. Binding beliefs: The creolisation process in a ‘Bushman’ raider group in nineteenth century southern Africa. In J. Deacon and P. Skotnes (eds.), The courage of ||Kabbo: Celebrating the 100th anniversary of the publication of specimens of Bushman folklore. Johannesburg: Jacana. Pp. 246–264.

Challis, S. 2018. Creolization in the investigation of rock art of the colonial era. In B. David and I. McNiven (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. New York: Oxford University Press. DOI:

10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190607357.001

Challis, S. & Skinner, A. 2021. Art and influence, presence and navigation in southern African forager landscapes. Religions special issue: Art, Shamanism and Animism, 12(12): 1099–1122. DOI: 10.3390/rel12121099

Challis, S. & Sinclair Thomson, B. In press. The impact of contact and colonisation on the indigenous worldview, rock art and history of southern Africa: the disconnect. Current Anthropology.

Coombes, A.E. 1994. Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture, and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Crumlish, N. & O’Rourke, K. 2010. A systematic review of treatments for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among refugees and asylum-seekers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(4): 237–251. DOI: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181d61258

Diederich, N.J., Goetz, C.G. & Stebbins, G.T. 2015. The pathology of hallucinations: one or several points of processing breakdown? In D. Collerton, U.P. Mosimann & E. Perry (eds.), The Neuroscience of Visual Hallucinations. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Dolin, K. 2013. ‘A beautiful fiction of law’: rhetorical engagements with Terra Nullius in the British periodical press in the 1840s. Journal of Victorian Culture, 18(4): 498–515. DOI: 10.1080/13555502.2013.857860

Fazel, M., Wheeler, J. & Danesh, J. 2005. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. The Lancet, 365(9467): 1309–1314. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6

Fewlass, H., Mitchell, P.J., Casanova, E. & Cramp, L.J.E. 2020. Chemical evidence of dairying by hunter-gatherers in highland Lesotho in the late first millennium AD. Nature Human Behaviour (2020): 1-9. DOI: 10.1038/s41562-020-0859-0

Fontana, A., Rosenheck, R. & Brett, E. 1992. War zone traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180: 748–755.

Froese, T., Woodward, A. & Ikegami, T. 2013. Turing instabilities in biology, culture and consciousness? On the enactive origins of symbolic material culture. Adaptive Behaviour, 21(3): 199–214.

Froese, T., Guzmán, G. & Guzmán-Dávalos, L. 2016. On the origin of the genus Psilocybe and its potential ritual use in ancient Africa and Europe. Economic Botany, 70: 103–114. DOI: 10.1007/s12231-016-9342-2

Fueshko, T.M. 2016. The intricacies of shell shock: a chronological history of The Lancet’s publications by Dr. Charles S. Myers and his contemporaries. Peace and Change, 41(1): 38–51.

George, M. 2010. A theoretical understanding of refugee trauma. Clinical Social Work, 38: 379–387. DOI: 10.1007/s10615-009-0252-y

Gersons, B.P.R. & Carlier, I.V.E. 1992. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: the history of a recent concept. British Journal of Psychiatry, 161: 742–748.

Gordon, R.J. 1992. The Making of the “Bushmen”. Anthropologica, 34(2): 183–202.

Gordon, R.J. and Douglas, S. 2000. The Bushman Myth: The Making of a Namibian Underclass. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Guenther, M. G. 1999. Tricksters and trancers: Bushman religion and society. Indiana University Press.

Guenther, M. 2006. N||àe (“Talking”): The Oral and Rhetorical Base of San Culture. Journal of Folklore Research, 43(3): 241-261.

Guenther, M. 2020. Human-Animal Relationships in San and Hunter-Gatherer Cosmology, Volume I. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hale, N.G. 1971. Freud and the Americans: The Beginnings of Psychoanalysis in the United States, 1876–1917. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hart, O., van Dijke, A., van Son, M. & Steele, K. 2000. Somatoform dissociation in traumatised World War I combat soldiers: a neglected clinical heritage. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 1(4): 33–66.

Helvenston, P.A. & Bahn, P.G. 2006. Archaeology or mythology? The ‘three stages of trance’ model and South African rock art. Les Cahiers de l’AARS, 10: 111–126.

Hendin, H., Pollinger Haas, A., Singer, P., Gold, F. & Trigos, G-G. 1983. The influence of precombat personality on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 24(6): 530–534.

Hewitt, R. 1986. Structure, meaning, and ritual in the narratives of the southern San. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Hitchcock, R.K. 2015. Authenticity, identity, and humanity: the Hai//om San and the state of Namibia. Anthropological Forum, 25: 262–284.

Kaiser, B.N., Haroz, E.E., Kohrt, B.A., Bolton, P.A., Bass, J.K., & Hinton, D.E. 2015. ‘Thinking too much’: a systematic review of a common idiom of distress. Social Science Medicine, 147: 170–183. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.044

Katz, R. 1984. Boiling energy: Community healing among the Kalahari Kung. Harvard University Press.

Kienzler, H. 2008. Debating war-trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in an interdisciplinary arena. Social Science and Medicine, 67(2): 218–227.

King, R. 2018. Among the headless hordes: missionaries, outlaws and logics of landscape in the Wittebergen Native Reserve, c. 1850–1871. Journal of Southern African Studies, 44(4): 659–680. DOI: 10.1080/03057070.2018.1475910

King, R. 2019. ‘Waste-Howling Wilderness’: The Maloti-Drakensberg as Unruly Landscape. In Outlaws, Anxiety, and Disorder in Southern Africa. Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series. Cambridge, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

King, R. & Challis, S. 2017. The ‘interior world’ of the nineteenth-century Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains. Journal of African History, 58(2): 213–237.

Kiras, J.D. 2019. Irregular warfare: terrorism and insurgency. In J. Baylis, J.J. Wirtz, & C.S. Gray (eds.), Strategy in the Contemporary World: An introduction to Strategic Studies (6th Edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pp. 183–201.

Kohda, K., Harada, K., Kato, K., Hoshino, A., Motohashi, J., Yamaji, T., Morinobu, S., Matsuoka, N. & Kato, N. 2007. Glucocorticoid receptor activation is involved in producing abnormal phenotypes of single-prolonged stress rats: a putative post-traumatic stress disorder model. Neuroscience, 148: 22–33.

Krediet, E., Bostoen, T., Breeksema, J., van Schagen, A., Passie, T. & Vermetten, E. 2020. Reviewing the potential of psychedelics for the treatment of PTSD. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(6): 385–400. DOI: 10.1093/ijnp/pyaa018

Lee, R. B. & Marshall, L. 1984. The Dobe !Kung. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Lewis, S.J., Arseneault, L., Caspi, A., Fisher, H.L., Matthews, T., Moffitt, T.E., Odgers, C.L., Stahl, D., Teng, J.Y. & Danese, A. 2019. The epidemiology of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in a representative cohort of young people in England and Wales. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(3): 247–256. DOI: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30031-8

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1986. Cognitive and optical illusions in San rock art research. Current Anthropology, 27(2): 171-178.

Lewis‐Williams, J.D. 1987. A dream of eland: an unexplored component of San shamanism and rock art. World Archaeology, 19(2): 165-177.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1992. Ethnographic evidence relating to ‘trance’ and ‘shamans’ among northern and southern Bushmen. South African Archaeological Bulletin, 47(155): 56–60.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 2015. Myth and meaning: San-Bushman folklore in global context. New York: Routledge.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. & Dowson, T.A. 1988. The signs of all times: entoptic phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic art. Current Anthropology, 29(2): 201-245.

Litz, B.T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W.P., Silva, C. & Maguen, S. 2009. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29: 695–706. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

Loo, C.M. 1994. Race-related PTSD: the Asian American Vietnam veteran. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 7(4): 637–656.

Loughran, T. 2012. Shell shock, trauma, and the First World War: the making of a diagnosis and its histories. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 67(1): 94–119. DOI: 10.1093/jhmas/jrq052

Low, C. 2007. Khoisan wind: hunting and healing. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, (N.S.): S71–S90.

de Luna, K.M. 2013. Affect and society in precolonial Africa. International Journal of African Historical Studies, 46: 123–150.

Macleod, A.D. 2004. Shell shock, Gordon Holmes and the Great War. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 97: 86–89.

Manson, S.M. 1997. Ethnographic methods, cultural context, and mental illness: bridging different ways of knowing and experience. Ethos, 25(2): 249–258.

Marmar, C.R., Schlenger, W., Henn-Haase, C., Qian, M., Purchia, E., Meng, L., Corry, N., Williams, C.S., Ho, C-L., Horesh, D., Karstoft, K-I., Shalev, A. & Kulka, R.A. 2015. Course of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder 40 years after the Vietnam War. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(9): 875–881. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0803

McGranaghan, M. 2012. Foragers on the frontiers: the |Xam Bushmen of the Northern Cape, South Africa, in the nineteenth century. DPhil thesis, Oxford University.

McGranaghan, M. 2014a. ‘He Who is a Devourer of Things’: Monstrosity and the Construction of Difference in |Xam Bushman Oral Literature. Folklore, 125(1): 1–21. DOI: 10.1080/0015587X.2013.865302

McGranaghan, M. 2014b. Different people, coming together: representations of alterity in |Xam Bushman (San) narrative. Critical Arts, 28(4): 670-688.

McGranaghan, M. 2015. ‘My name did float along the road’: naming practices and |Xam Bushman identities in the 19th-century Karoo (South Africa). African Studies, 74(3): 270-289.

McGranaghan, M. & Challis, S. 2016. Refiguring hunting magic: southern Bushman (San) perspectives on taming and their implications for understanding rock art. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 26(4): 579-599.

Myers, C.S. 1916. Contributions to the study of shell shock: being an account of certain disorders of speech, with special reference to their causation and their relation to malingering. The Lancet, 188: 461–467.

Netz, R. 2004. Barbed Wire: an Ecology of Modernity. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Ouzman, S. & Loubser, J. 2000. Art of the apocalypse: southern Africa’s Bushmen left the agony of their end time on rock walls. Discovering Archaeology, 2: 38–45.

Pagel, J.F. & Broyles, K. 2019. Indications that a northern New Mexico petroglyph was inspired by a traumatic nightmare. Dreaming, 29(2): 196–209. DOI: 10.1037/drm0000105

Peterson, M.J. & Benca, R.M. 2006. Sleep in mood disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29: 1009–1032. DOI: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.09.003

Phillips, C.G. (ed.) 1979. Selected papers of Gordon Holmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Robinett, J. 2008. The narrative shape of traumatic experience. Literature and Medicine, 26(2): 290–311.

Roche, C. 2008. ‘The fertile brain and the inventive power of man’: anthropogenic factors in the cessation of springbok treks and the disruption of Karoo ecosystems, 1865-1908. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 78(2): 157–188.

Royal Army Medical Corps. 1922. Report of the War Office Enquiry into ‘Shellshock’. London: H.M.S.O.

Sack, W.H., Seeley, J.R. & Clarke, G.N. 1997. Does PTSD transcend cultural barriers? A study from the Khmer Adolescent Refugee Project. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(1): 49–54. DOI:

10.1097/00004583-199701000-00017

Siegel, R.K. 1977. Hallucinations. Scientific American, 237: 132–140.

Siegel, R.K. & Jarvik, M.E. 1975. Drug-induced hallucinations in animals and man. In Hallucinations: Behaviour, Experience and Theory, edited by R.K. Siegel & M.E. Jarvik, pp. 81–161. New York: Wiley.

Sinclair Thomson, B. & Challis, S. 2017. The ‘bullets to water’ belief complex: a pan-southern African cognate epistemology for protective medicines and the control of projectiles. Journal of Conflict Archaeology, 12(3): 192–208. DOI: 10.1080/15740773.2017.1487122

Sinclair Thomson, B. & Challis, S. 2020. Runaway slaves, rock art and resistance in the Cape Colony, South Africa. Azania, 55(4): 475–491. DOI: 10.1080/0067270X.2020.1841979

Simpson, E. 2013. War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First-Century Combat as Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skinner, A. 2021a. Politics of identity in Maloti-Drakensberg rock art research. In S. Chirikure (ed.), The Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of African Archaeology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Skinner, A. 2021b. Valley of Snakes: Rock Art and Landscape, Identity and Ideology in the South-Eastern Mountains, Southern Africa. PhD Dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand.

Skinner, A. & Challis, S. 2022. Fluidities of personhood in the idioms of the Maloti-Drakensberg, past and present, and their use in incorporating contextual ethnographies in southern African rock art research. Time and Mind. DOI: 10.1080/1751696X.2022.2079422

Smith, B.W. 2010. Envisioning San history: problems in the reading of history in the rock art of the Maloti-Drakensberg mountains of South Africa. African Studies, 69(2): 345–359.

Stein, G.J. 2005. The Archaeology Of Colonial Encounters: Comparative Perspectives. Oxford: James Currey Ltd.

Stewart, B.A., Zhao, Y., Mitchell, P.J., Dewar, G., Gleason, J.D. & Blum, J.D. 2020. Ostrich eggshell bead strontium isotopes reveal persistent macroscale social networking across late Quaternary southern Africa. PNAS, 117(12): 6453–6462. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1921037117

Torrance, S. & Froese, T. 2011. An inter-enactive approach to agency: participatory sense-making, dynamics, and sociality. Humana. Mente 15: 21–53.

Wessels, M. 2007. The Discursive Character of the ǀXam texts: A Consideration of the ǀXam ‘Story of the Girl of the Early Race, who made stars’. Folklore, 118(3): 307-324.

Wessels, M. 2010. Bushman Letters: Interpreting /Xam Narrative. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Wiessner, P. 2005. Norm Enforcement among the Ju/'hoansi Bushmen. Human Nature, 16(2): 115-145.

Woodward, S.H., Arsenault, N.J., Murray, C., & Bliwise, D.L. 2000. Laboratory sleep correlates of nightmare complaint in PTSD inpatients. Biological Psychiatry, 48(11), 1081-1087.

Yaden, D.B. & Griffiths, R.R. 2021. The subjective effects of psychedelics are necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science, 4: 568–572. DOI: 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00194

Yehuda, R., Southwick, S.M. & Giller, E.L. 1992. Exposure to atrocities and severity of chronic postraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam combat veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149: 333–336.

Yehuda, R. 2002. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The New England Journal of Medicine, 346(2): 108–114.

Yehuda, R., Hoge, C.W., McFarlane, A.C., Vermetten, E., Lanius, R.A., Nievergelt, C.M., Hobfoll, S.E., Koenen, K.C., Neylan, T.C. & Hyman, S.E. 2015. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 1, 15057. DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.57

Zefferman, M.R. & Mathew, S. 2021. Combat stress in a small-scale society suggests divergent evolutionary roots for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. PNAS, 118(15): 1–10. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2020430118

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation