Aron Mazel

Newcastle University and University of the Witwatersrand

The Digging Stick, Vol 40 (1), April 2023

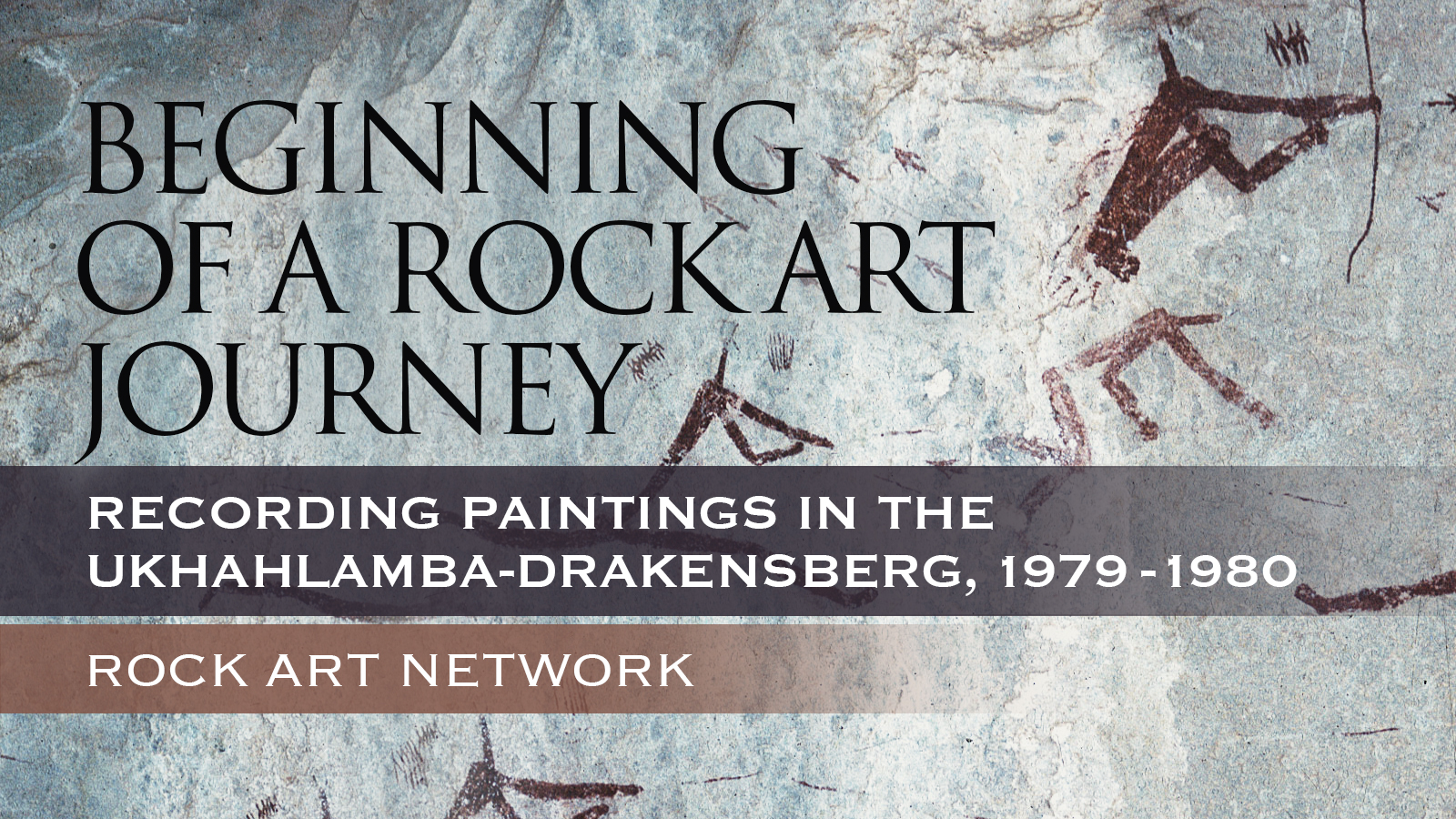

I got lucky early on in my career! Fresh out of university, I obtained a job to locate and record rock paintings, surface archaeological remains and sites with potential archaeological deposits in the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Mountains (Figure 1). I moved from Cape Town, where I had grown up and attended university, to Pietermaritzburg, 1 600 km away, in the northeast of the country. This involved receiving a lift halfway and then hitchhiking the rest of the way, arriving on a Sunday night early in January 1979. The next day, I started my professional career at the Natal Museum, now the KwaZulu-Natal Museum, where the post was based. This was the beginning of a rock art journey that is still ongoing.

I was tasked to do Phase 2 of a project that was funded by the Department of Forestry, which controlled most of the mountains at the time. It lasted between January 1979 and March 1981. Phase 1 had been undertaken by Val Ward who had focused on collating known site records and initiating the fieldwork programme. The information collected during the project was mostly intended for management planning, based on the idea that effective planning required detailed, consistent and accurate information. It was the first rock art project of its kind in South Africa. My final report entitled, ‘Up and down the little berg: archaeological resource management in the Natal Drakensberg’, also served as my MA dissertation for the University of Cape Town (1981). The project involved 14 fieldtrips, 13 for recording rock art and another to do trial excavations at four rock shelters. The trips were generally three weeks long. Mostly they were solo trips although I was occasionally joined by students, friends and colleagues. Altogether, I recorded 333 painted sites, containing 18 867 paintings, and 55 non-painted sites with surface artefacts. Many sites and paintings were being recorded for the first time; for example, 3 748 of the paintings recorded, or 20 per cent of the total, were from previously unrecorded sites. The sites were typically at the base of sandstone cliffs, although there were also paintings on large, dislodged boulders. In 1980, I took paint samples for an AMS radiocarbon dating project at Never-ending Shelter, Cyprus 3 and Bundoran 1. Unfortunately, none of these samples yielded dates, but significantly the project did produce the first ever AMS radiocarbon date in the world on a rock painting from the south-western Cape (Van der Merwe et al. 1987).

Paintings were recorded through detailed written descriptions, supplemented by colour transparencies and monochrome photography. As far as possible, the photographic recording followed the same sequence as the written descriptions, i.e. working from left to right and top to bottom. About 16 000 black and white images and colour transparencies were taken. (I often wonder how many images would have been taken had this been during the digital age!) A Management Data Questionnaire was also completed at each site. All these records are housed at the KwaZulu-Natal Museum. Another feature of the site recording was to systematically glue a stainless steel Dymo tape strip, with the national site numbers punched onto it, at the bottom left of each site, which identified it as recorded. In total, 341 strips were adhered. In hindsight, these strips were not the most effective conservation practice, especially as the epoxy glue has tended to discolour over the years rendering many numbers unreadable. It must be remembered though that the project occurred well before the advent of GPS and we wanted, as best we could, to ensure that people knew which sites had been recorded to prevent duplication, a problem that had occurred up until then.

Fieldtrips involved setting up base camps and working out from them on a daily basis. Base camps included private homes, lodgings for inspection officers and researchers, caravans and rock shelters deep in the mountains, where Forest and Game guards skilfully guided horses with my provisions and equipment in panier bags (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Living in rock shelters made for some interesting experiences. One day I thought I might have to spend the night with a troupe of baboons. After recording Clarke’s Shelter, I returned to Eland Cave, my base camp, in the late afternoon to find a troupe close to and in the site, which meant they were planning to overnight there. It was cold with snow on the mountains (Figure 4). I did not want to sleep outside and risk hyperthermia, especially as my trousers were already sodden from walking through long wet grass. Moreover, all my food was in the shelter and the nearest access point was too far away to risk walking out in the dark. Deciding to risk sharing the place with the baboons, I kept walking towards them with my walking stick and a firm gait. The closer I got, the louder and more intense the baboons barked. When I was about 50 m away, the baboons begrudgingly moved off, leaving me to enjoy a restful and warm night in the place that was my home for that week.

Considering sleeping places, at Vergelegen Nature Reserve, in March 1980, I slept in my project vehicle for four nights as the area above the ‘squaredawel’, as these living quarters were called, had been declared a landslide zone by engineers. We agreed that I could move my provisions into the squaredawel and use it for everything except sleeping. Come bedtime, I would relocate down the hill to a safer place (Figure 5). For a couple of nights, I did not drive the vehicle up the to the quarters as it was not a 4-wheel- drive and I feared it would slip off the muddy track and after rainy days ‒ a dread informed by the fact I had to be pulled out of mud by 4-wheel-drive vehicles and tractors on previous trips.

My first project fieldtrip was to the Kamberg Nature Reserve with Val Ward, starting on 31 January 1979. Val introduced me to the mountains and its rock paintings and together we initiated my recording programme. Over 40 years later, I can still clearly remember my trepidation at seeing the mountains for the first time. They were huge, and I now had to walk them! I was familiar with mountains as I had grown up in the shadow of Cape Town’s Table Mountain, but the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Mountains were significantly more imposing. Terrifyingly, I had the daunting task of spending much of the next two years walking up and down them unsure that I would survive! This concern was exacerbated by my lack of fitness at the time. Later, I discovered that my initial apprehension was shared by conservation management staff who I encountered at the beginning of the project, who had taken bets about how long I would last, with the favoured timeframe being less than six weeks. Not only did I prove them wrong, but more importantly I proved myself wrong. I plotted my walk-route daily on a 1:50 000 map sheet and estimated the distance carefully. I calculated at the end of the project that I had walked a minimum of 1 681 km (671 km in 1979 and 1 010 km in 1980). I emphasise minimum because working on a map with a piece of string would not have registered all my ups and downs and side steps. Moreover, on one trip I used a pedometer, strapped to my ankle, that gave me a higher reading of some 15 per cent: 92 km on the map and 105 km on the pedometer. The pedometer was abandoned thereafter as it was uncomfortable. Although my preferred mode of travel was on foot, occasionally I was placed on a horse and did my utmost not to fall off, although this did happen shortly after the project ended.

Back to my Kamberg trip, I would love to say that the first painted site I visited was the world-renowned Game Pass Shelter 1. Instead, it was Waterfall Shelter, which is en-route to this site from the camp. I first visited Game Pass 1 six days later with Val and Tim Maggs, who had joined us for the day. We spent the afternoon examining the paintings and discussing how best to record them. I spent the next two days recording 367 paintings in the site and 42 in the adjacent site of Game Pass 2. That initial fieldtrip showed me that the sites contained a wide range and a large number of paintings: from a single eland at Pluto 3 to hundreds of paintings at Game Pass 1. The most paintings recorded at any one site in the mountains is 1 639 at Eland Cave (Pager 1971), while the most I recorded was 1 235 at Battle Cave, which resulted in 39 typed pages, including small sketches of some of the paintings (Figure 6).

Early on during fieldwork, I also learnt that often there were many more paintings at a site than what there appeared to be at first glance! At Sigubudu 1, in Royal Natal National Park, which I recorded during my second fieldtrip in March 1979, I wrote in my daily journal: ‘Initially, the paintings looked very faded and uninteresting, however, on closer inspection there were greater than 300 paintings, with some interesting paintings – especially the humans with rifles’. I recorded 315 paintings there.

At Royal Natal I also realised that areas that had not previously been comprehensively searched, were likely to have many more sites than were on record. Here, the painted sites increased from 15 to 25, while 10 sites with only surface archaeological material were added to the record. As time went on, the value of local knowledge became evident as the park’s Warden, Ron Physick, after reviewing the directions to and descriptions of paintings at two recorded sites advised that they were likely to be the same site, which proved to be the case. Invariably, confusions like this were exacerbated when people provided inaccurate map locations, something I suspect I was also occasionally guilty of. The biggest incorrect distance I encountered between a location provided to the museum and the actual location was 7 km, which meant that the site was outside the project area.

Throughout the fieldwork, advice from conservation staff was invaluable in locating sites. Of particular help was Bill Small, then the Forester at Cobham State Forest, whose great interest in the paintings led to him mapping many new sites for me, leading to the doubling of recorded sites at Cobham from 49 to 106. Increased site numbers of this kind answered a question that I was often asked during the project: ‘But surely this area has been investigated before; is there a need to cover it again?’

Not only was local knowledge important for locating known sites and finding unrecorded sites, but also, on occasion, it was invaluable when my stuff and I were transported around the mountains. One trip I remember well, occurred in September 1979, when John Hlongwane and Sokola Mdluli, Cathedral Peak forest guards, relocated me and my panier bags ‒ filled with clothes, food and other stuff ‒ on horseback from Eland Cave, where I had stayed the previous week, to Zunckels Cave. Shortly after we departed Eland Cave, it started raining hard and a thick mist descended on us, severely limiting our visibility. It remained like this for the rest of day, but they delivered me safely to the cave! To this day, I have no idea of what route they took, although I know it involved crossing the Mhlwazini River. Dutifully, I sat on the horse all the way!

Not only was mist a problem on the trip from Eland Cave to Zunckels Cave, but it was ever-present during field work and there were several times when I would have to wait, occasionally in the shelter I was staying in, until the mist lifted before venturing out. In fact, I lost one-and-a-half of the six days I spent at Zunckels Cave to mist. Another memorable encounter I had with mist was with Albert Zondi, a forest guard at Garden Castle. In October 1980 we set out early from Garden Castle as Albert was going to guide me to Fun Cave in the upper Mzimkhulu Valley to meet up with Clem Robbins and a party he was leading, including journalist Melanie Gosling. I noted in my daily journal: ‘For most of the day we couldn’t see more than a couple of hundred meters ahead of us. At about 4pm we decided to find a shelter to spend the night’. Luckily, we found a small shelter and huddled into it. After an uncomfortable night, we awoke to a clear sky and realised that we were not in the upper Mzimkhulu Valley, as we thought, but in the adjacent lower Thukelana Valley and a substantial way from our destination. A long walk ensued to correct course! After meeting with Clem and the others, it was decided that we would not make it to Fun Cave by nightfall. Instead, we camped in Mayo Cave, where an onsite interview with Melanie led to my first-ever newspaper article (Gosling 1980), with the following ending, ‘As he climbs aboard the four-wheel drive and bumps up the mountain road back to work, I can’t help wondering how many little grey men in Durban would gladly give their monthly bus coupons to be able to swop jobs for just one day with Aron Mazel’ (Figure 7).

Notable weather events were not restricted to mist. I got caught in many heavy downpours and even hailstorms. The most frightening of these occurred on 7 February 1980 while recording Battle Cave in the Injasuthi Valley. Although lightning was common in the mountains, it was particularly fierce on that day. My tension was exacerbated by the fact that about six weeks previously, two people had been killed relatively close by in a powerful lightning storm: ‘A game ranger, John Clarke and his girlfriend, Carol Richter, together with their dog, were killed by lightning during a “dry storm” on the 20th December 1979. They were standing on a ledge overlooking the Injasuthi Valley at the time, watching the storm build up’ (Pelser 2019). Cognisant of this tragedy, I snuggled close to the rockface while recording, especially as Battle Cave is not a very deep site.

In the preface to the MA, I wrote (1981: i): ‘Thinking about the project, and leaving aside the research results and conservation recommendations, the first thing which comes to mind is the large number of people who have assisted in one way or another to ensure the successful completion of this project and the final write-up’. This sentiment, together with the immense privilege of being able to document the significant and world-renowned imagery created by the San hunter-gatherers, and perhaps also by pastoralists and Bantu-speakers, still lives on strongly within me 40 years later!

Gosling, M. 1980. Mountain man Aron charts rock art heritage. The Natal Mercury, 28 October, 7.

Mazel, AD. 1981. Up and down the Little Berg: archaeological resource management in the Natal Drakensberg. MA thesis. University of Cape Town.

Pager, H. 1971. Ndedema: a documentation of the rock paintings of the Ndedema Gorge. Graz: Akademische Druck.

Pelser, W. 2019. Thunderstorms in the Drakensberg mountains. https://hikingthedrakensberg.blogspot.com/2017/05/thunderstorms-in-drakensberg-mountains.html; accessed 29 November 2020).

Van der Merwe, NJ, Sealy, J & Yates, R. 1987. First accelerator carbon-14 date for the pigments from a rock painting. South African Journal of Science 83: 56‒57.

Aron Mazel is a Research Associate at Newcastle University, United Kingdom, and the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. aron.mazel@ncl.ac.uk Photos by Aron Mazel unless indicated otherwise.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation