Levan Losaberidze is an archaeologist and rock art researcher focusing on the South Caucasus and the Middle East. He is the founder of GARA Georgian Association of Rock Art, an IFRAO member organisation. Since 2017, he has been studying rock art in Georgia, aiming to advance the state of the art of rock art heritage in the country. During this period, he has published several international peer-reviewed papers on the rock art of various chronological periods in Georgia.

He studied rock art at Instituto Politécnico de Tomar in Portugal. He has gained field experience at rock art sites in Georgia, Portugal and the United Arab Emirates. In 2019, he received a student research award from ARARA for his fieldwork at the Damirgaya rock art site.

A wealth of evidence indicates extensive occupation in Georgia since prehistoric times. However, rock art had not been a significant part of the series of discoveries. In the context of rock art, it is especially important to highlight that we discuss the period since anatomically modern humans (hereafter AMH) appeared in this territory (circa 40,000 cal. BP) because this species is directly linked to the creation and development of the art.

In terms of the Pleistocene art created by AMH, the region at the crossroads of Eastern Europe and Western Asia has become more interesting due to recent discoveries, namely in the Balkan Peninsula, Ukraine, Caucasus, etc. The Caucasus, in general, is one of the least studied regions from the rock art point of view. The recent discovery of Upper Palaeolithic rock art in western Georgia, along with well-known evidence from Gobustan (Azerbaijan), demonstrates that the region is another significant spot outside Western Europe where Palaeolithic rock art has been observed.

Besides the Palaeolithic period, although the total number of rock art sites is limited, Georgia offers a wide range of geographical and geological settings, as well as chronology and techniques. Geographically, rock art sites are primarily distributed in two regions – western and southern Georgia. This is well explained by geological characteristics. Western Georgia contains a large accumulation of karstic settings, particularly limestones. On the other hand, southern Georgia is composed of pseudo-karstic volcanic landscapes, and it is known for the abundance of rocky outcrops, rock shelters, etc.

From a chronological point of view, alongside Mghvimevi, the cave site Agtsa, located far northwestern, represents Palaeolithic non-figurative rock art. The post-Palaeolithic period is represented by Trialeti Petroglyphs, a multiperiod site spanning a long chronology including Neolithic, Early Bronze Age, Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Age, and Medieval Age. Another site Damirgaya is considered the Neolithic chronology. Other less-known sites contain Bronze Age and Medieval sequences. In terms of techniques, both Palaeolithic sites contain engraving techniques, namely incision and carving; Trialeti petroglyphs contain incision technique, as well as recently discovered paintings; and Damirgaya is represented by paintings only.

Mghvimevi is a site complex composed of limestone karst that contains two caves and five rock shelters. It is located on the right bank of the Kvirila River, near the town of Chiatura

This burgeoning interest found expression in the significant regional congress in Tbilisi in 1881. The Annual Archaeological Congress of the Imperial Russian Archaeological Society took place in Moscow, Saint-Petersburg, Kyiv, and Kazan in previous years. In Tbilisi, the congress was attended by 400 participants, including the leading European scholars of that day, such as Oscar Montelius, Rudolf Virchow, Heinrich Schliemann, Gabriel de Mortillet, Ernest Chantre, etc.

In the ensuing years, A. Joakimov, a member of the Caucasus Archaeological Society, made an interesting discovery in Tsalka, southern Georgia. He relayed his findings to historian E. Weidenbaum in a letter:

“Merciful tsar,

Evgeniy August, it is very unfortunate that you could not come to Tsalka and here is why: Imagine that in the river gorge near the village Tak-Kilisa, I discovered caves with hunting scenes on the walls. This is a whole gallery of paintings of savages who lived once in Tsalka.“

However, this discovery was not recorded by A. Joakimov, and information about the site remained lost for almost a century. It was only in the 1970s that the Trialeti Archaeological Expedition led by M. Gabunia, with the aid of the above-mentioned letter, was able to rediscover the site. Today, it is commonly known as the Trialeti petroglyphs, also referred to as Tsalka petroglyphs or Patara Khrami petroglyphs.

Early Soviet Era (1930s)

This decade marked the beginning of studies on the Stone Age in Georgian archaeology. Alongside a few Georgian pioneer Stone Age archaeologists, several eminent Russian scholars carried out research, particularly in western Georgia. Among the leading Russian archaeologists in the Caucasus were Sergey Zamyatnin and Leo Solovyov, who studied numerous cave sites. Both found Upper Palaeolithic rock art, although far away from each other, in Mghvimevi and Agtsa respectively. Despite their significance, these discoveries have been neglected for decades.

Mghvimevi, a complex of caves and rock shelters, was discovered in Chiatura, western Georgia in 1934. Sergey Zamyatnin noted that rock shelter No.5 stood out as the most interesting among the karst features due to the evidence of Pleistocene rock art. He observed a number of abstract signs engraved on the floor of the rock shelter.

Another site with Palaeolithic engravings was discovered in the Abkhazeti region of northwest Georgia in 1937. Leo Solovyov examined the cave known as Agtsa, where local honey collectors had noticed various pictograms, including human hands, circles, zigzags, crosses, and inscriptions. The letters were identified as the ancient Georgian script Asomtavruli, which was in use between the 5th and 8th centuries AD. More importantly, the scholars discovered a panel featuring abstract signs associated with the Upper Palaeolithic period.

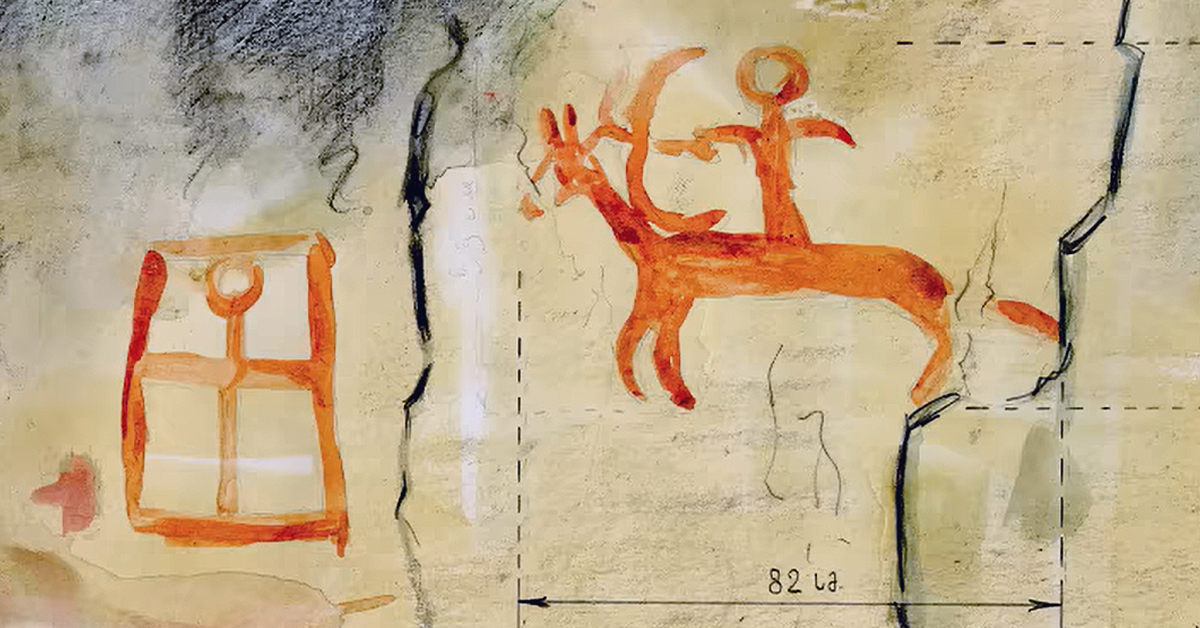

During WWII, in 1939 and 1945, two campaigns were conducted in the Khvamli massif in western Georgia. This vast limestone massif has been known from historical sources as the treasure storage for Georgian kings. A team of alpinists and archaeologists climbed up to the rock cuts where they found manmade structures built into hollows and some pottery sherds. Surprisingly, they observed massive red-painted figures (approximately 40-50 cm in dimensions) on the walls, portraying horse raiders and abstract signs.

Cold War (Post-WWII) Era (1950s-1980s)

A new phase in Soviet archaeology emerged with the expansion of infrastructure projects, leading researchers to engage in what we now refer to as rescue archaeology.

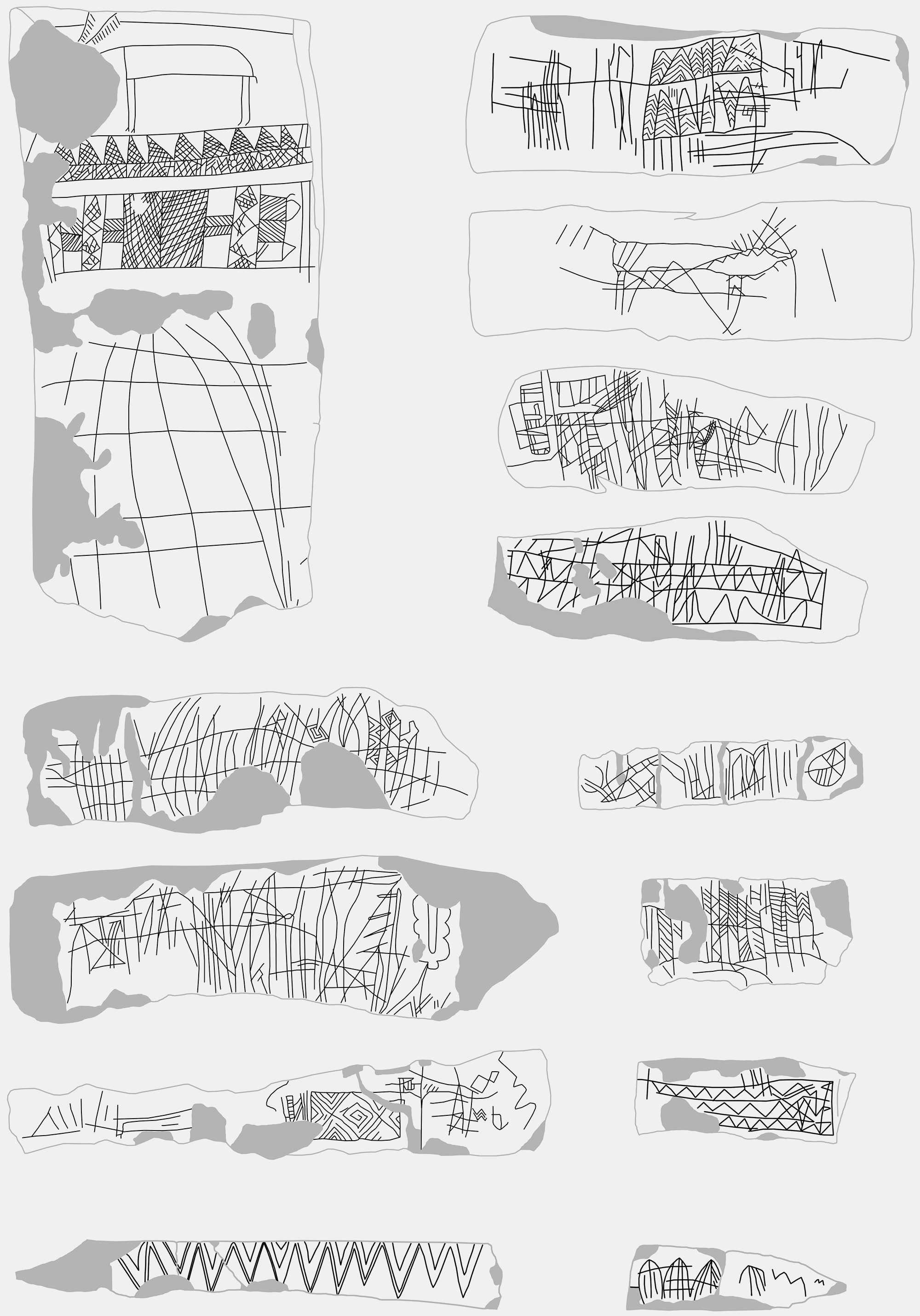

Between 1959 and 1964, excavations led by O. Japaridze uncovered several kurgans, i.e. massive burial mounds, where hundreds of engraved slabs were observed both in the dromos and burial chambers. These kurgans are characterized by the absence of anthropological remains. Instead, cremation is suggested to be a common tradition in the context of the Middle Bronze Age Trialeti culture. Cremated bodies were interred on wooden chariots or beds.

The engraved slabs within the burial chambers were scattered chaotically rather than arranged in a specific order. An additional number of slabs was discovered in the dromos, i.e. the entrance of the kurgan construction.

On the other hand, in 1976, the Trialeti Archaeological Expedition led by M. Gabunia rediscovered the Trialeti petroglyph site that had been lost for almost a century. Gabunia recorded the area with the highest concentration of petroglyphs, identifying 6 main panels containing approximately 100 images.

Not long after, in 1981, Tamaz Kiguradze conducted an archaeological excavation at the Neolithic settlement Khramis Didi Gora. During this season, he was informed about a rock shelter (known as Damirgaya) with some paintings in the vicinity of an archaeological site. Kiguradze visited the location and described the evidence; however, he did not record the rock art, so it remained unattended for decades.

Independence Epoch (1990s-2020s)

In 2001, a group of researchers discovered petroglyphs on medieval towers in northeast Georgia. Later in 2010, this team expanded their study area, conducting surveys across Georgia to identify potential locations with rock art. The project “Talking Stones” spanned 3 years and resulted in the publication “Big Catalogue of Georgia Petroglyphs”.

In 2012, Gabunia revisited the Trialeti site and identified several new panels. The results were presented in the publication in 2019.

Conversely, in 2017, the National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation of Georgia initiated the process of joining the Prehistoric Rock Art Trails network where they represented the Trialeti Petroglyphs. Later in 2019, the Agency conducted a survey at Trialeti in order to explore a larger area beyond the main panels. As a result, several new locations were identified. Furthermore, one new panel revealed two images of rock paintings, marking the first discovery of painted rock art at Trialeti and only the second instance in Georgia after Damirgaya.

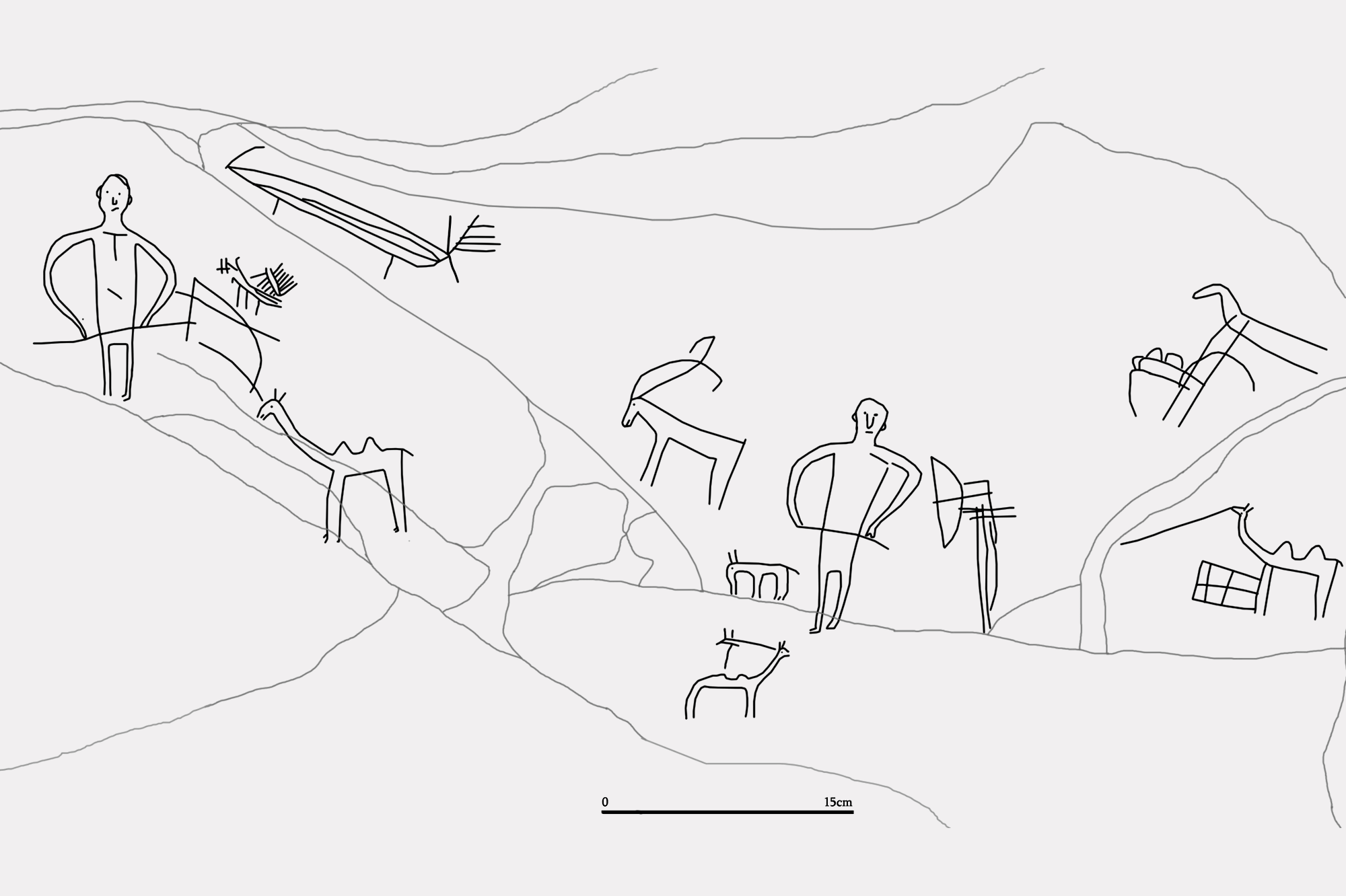

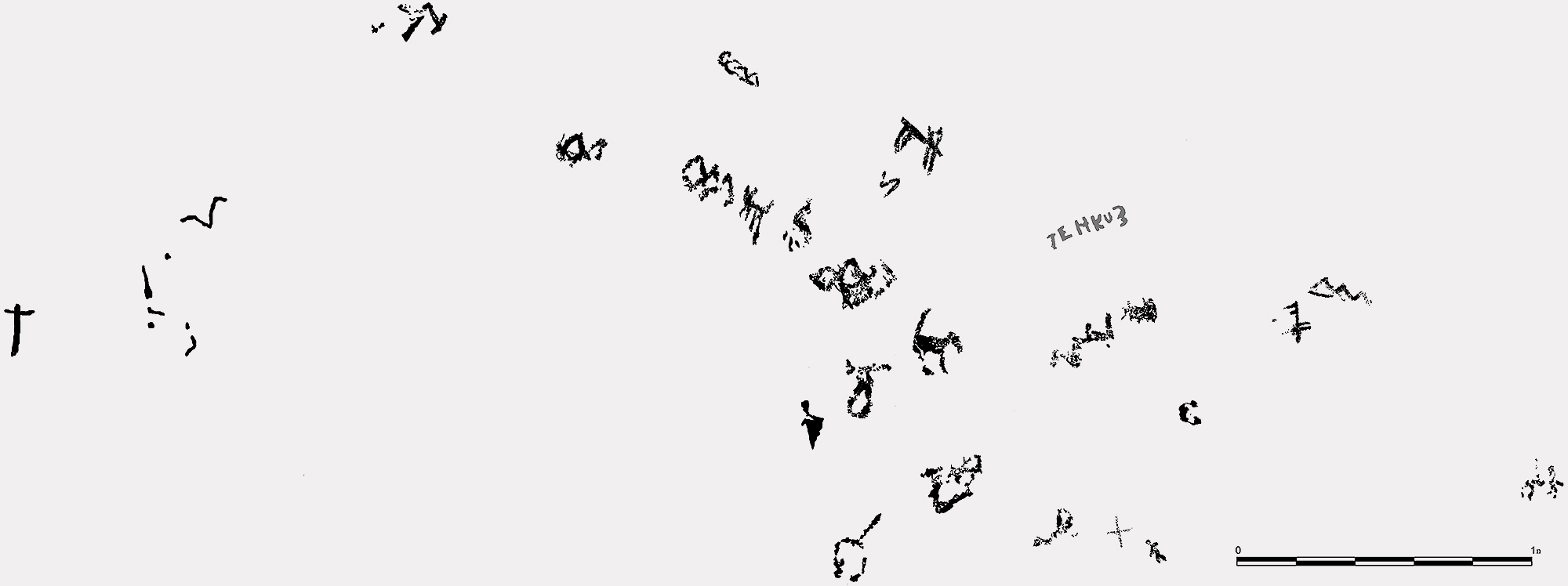

Speaking of Damirgaya, it was rediscovered in 2017 after noticing a short description in Kiguradze’s report on archaeological excavation at the Neolithic settlement. As mentioned earlier, Kiguradze had not presented any photos or drawings of the rock art site; instead, only the name of the site and the nearest village were known. Therefore, a survey of the area was intended to attempt to rediscover the forgotten site. Eventually, it was located on the slope of the ridge bordering Georgia and Armenia. In 2020, comprehensive research was conducted at Damirgaya with funding from the American Rock Art Research Association. The study revealed that the paintings are depicted in a schematic style and comprise zoomorphic, anthropomorphic, and geometric motifs. The zoomorphic figures are represented by the animals like bovids, canids, and caprids.

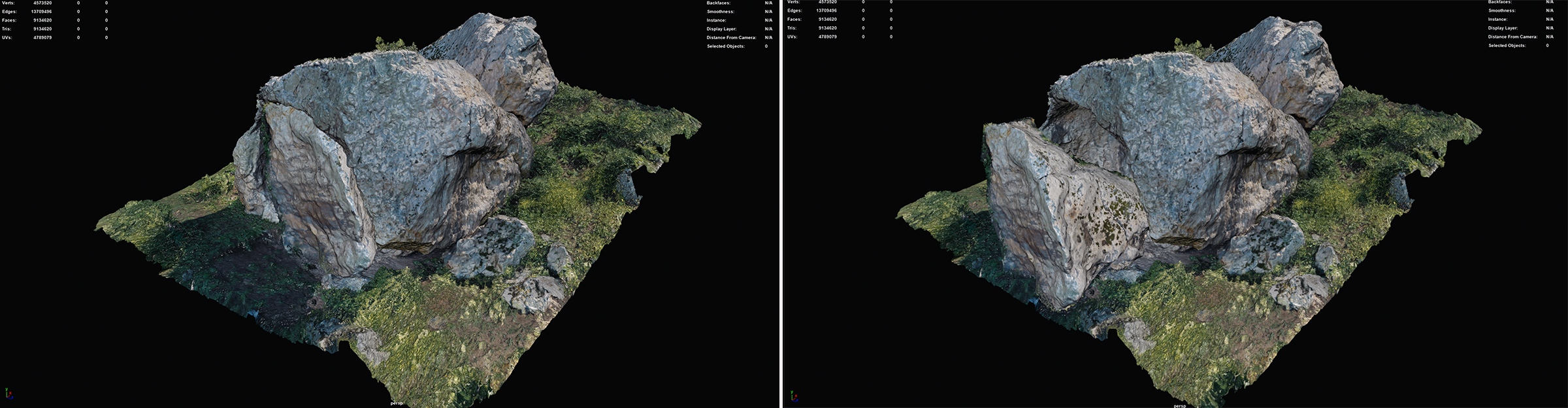

In 2022, another important rock art site was rediscovered by our team. Mghvimevi, the site complex containing caves and rock shelters, is situated in western Georgia and has been known as one of two Palaeolithic rock art sites found in Georgia. However, these discoveries had been neglected by scholars for decades. Mghvimevi rock art was even considered lost because later researchers could not observe the engravings once found by the Russian archaeologist Sergey Zamyatnin in 1934. Our team revisited the site and located the engravings on the floor of rock shelter No.5. Over two years of fieldwork, nearly 30 engravings have been identified, distributed over a 54m2 area. All of the engravings are non-figurative motifs, more specifically, linear marks. They comprise vertical, horizontal, and diagonal lines which sometimes intersect.

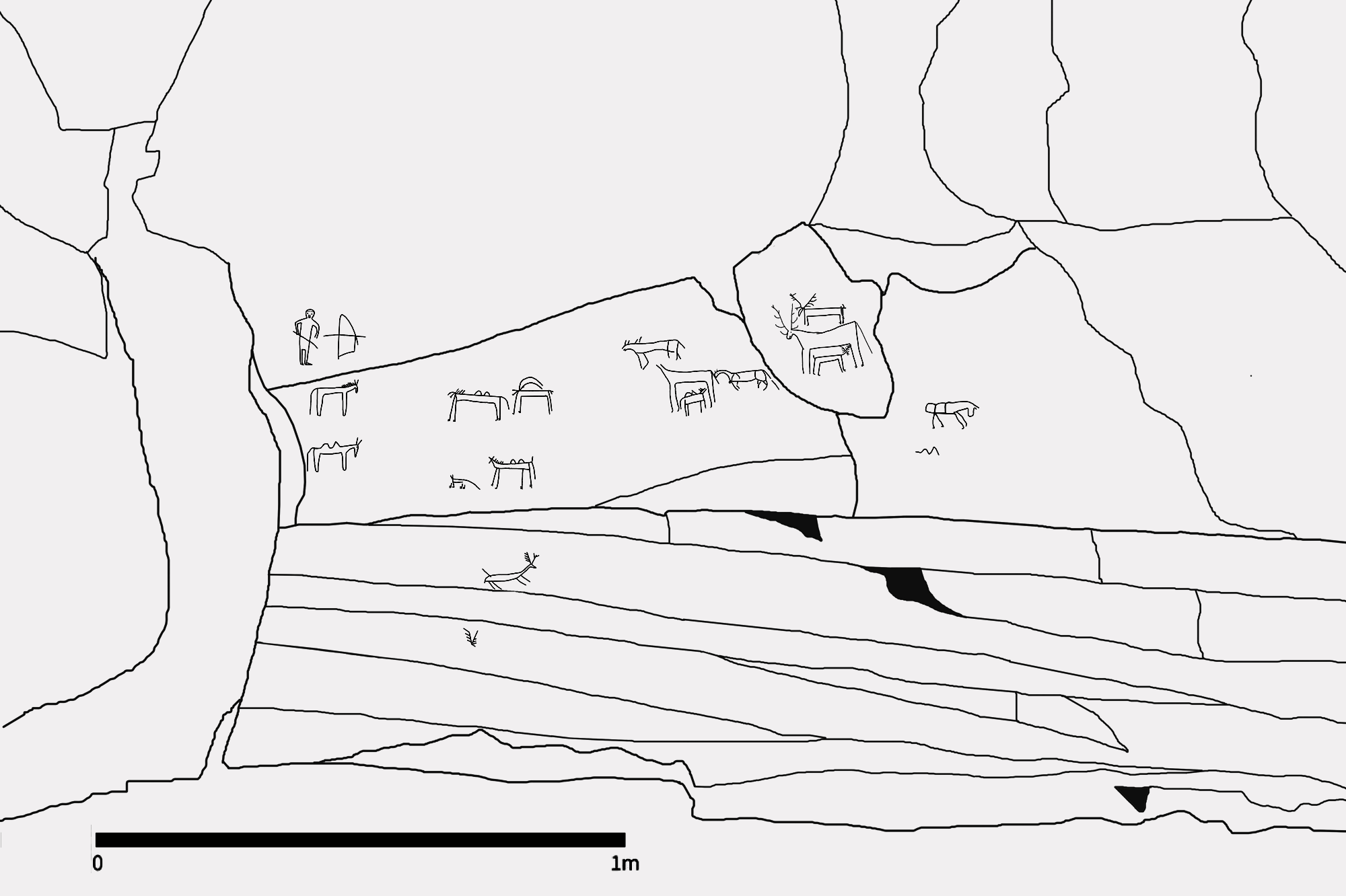

In 2023, our team revisited Trialeti, the most extensive rock art site found in Georgia so far. As discussed above, after its initial study in 1976 by M. Gabunia, there were several recent attempts, however not comprehensive, to contribute to the studies of this site. Therefore, we intended a reassessment of the originally identified six panels to advance the state of the art of the Trialeti rock art. As a result, 103 figures have been recorded over these six panels. They are primarily incised engravings. The figurative repertoire comprises zoomorphic, anthropomorphic, and geometric figures. Other categories are weapons (bow and arrow), religious signs (cross), and abstract signs.

“Major rock art provinces occur wherever suitable bedrock exists” (McDonald and Veth 2012). This statement applies universally to every part of the world, including the diverse landscapes of Georgia. Although only a few rock art sites have been discovered in Georgia so far, their distribution, in combination with geological, geographic, and archaeological observations, gives us a clue about the main rock art provinces in the country. Closer observation of the placement of karst landscapes across Georgia reveals where rock art sites are located and where potential new sites can be found in the future. There are two main areas where rock art sites have been discovered – western Georgia, Rioni-Kvirila Basin in particular, where numerous cave complexes, composed of limestone karst, are located; and southern Georgia, encompassed by the Kura River valley, where the landscape has developed after volcanic activities, is another rock art province.

Two rock art sites are discovered in the Rioni-Kvirila Basin – Mghvimevi and Khvamli.

Mghvimevi

Mghvimevi is a site complex composed of limestone karst that contains two caves and five rock shelters. It is located on the right bank of the Kvirila River, near the town of Chiatura. Rock shelter No.5 is the only location where rock art, specifically engravings, was discovered. This rock shelter faces south-southwest. It is 21.5 m long, 4 m high, and extends 2.5 m back from the drip line, giving it a hollowed-out appearance.

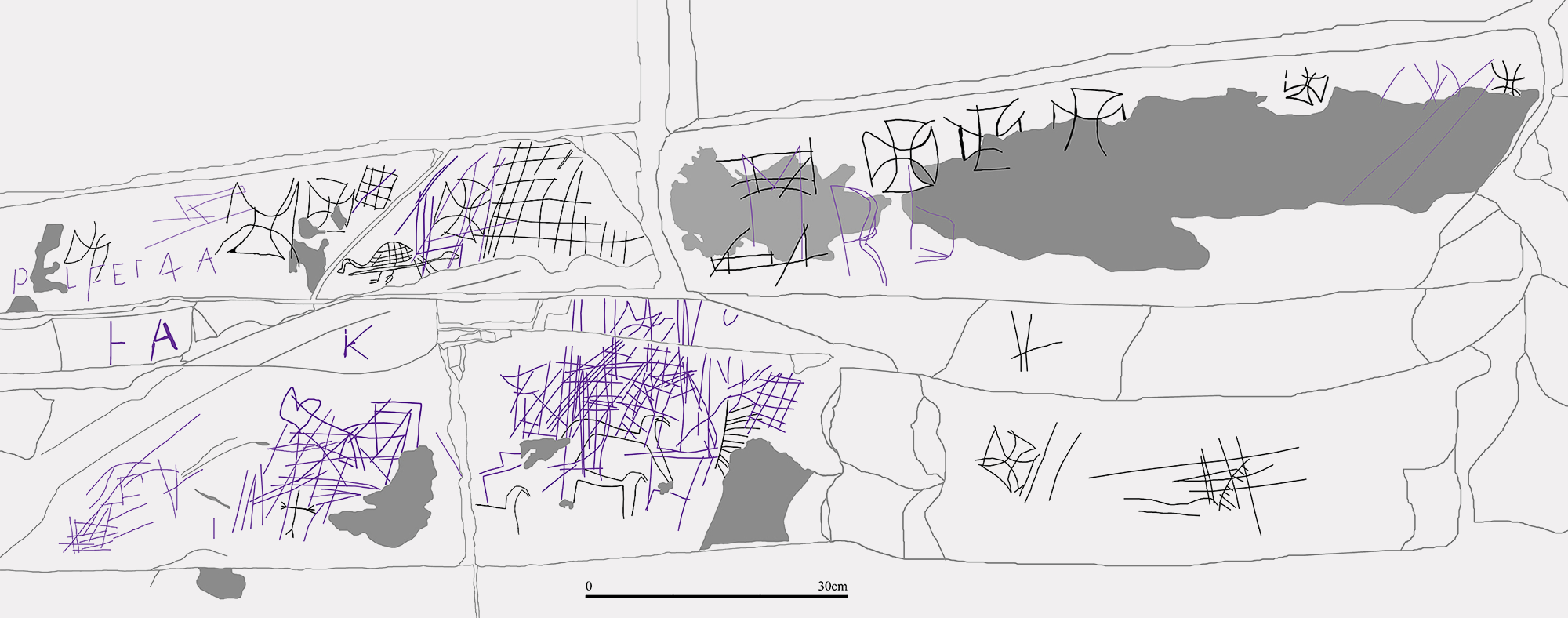

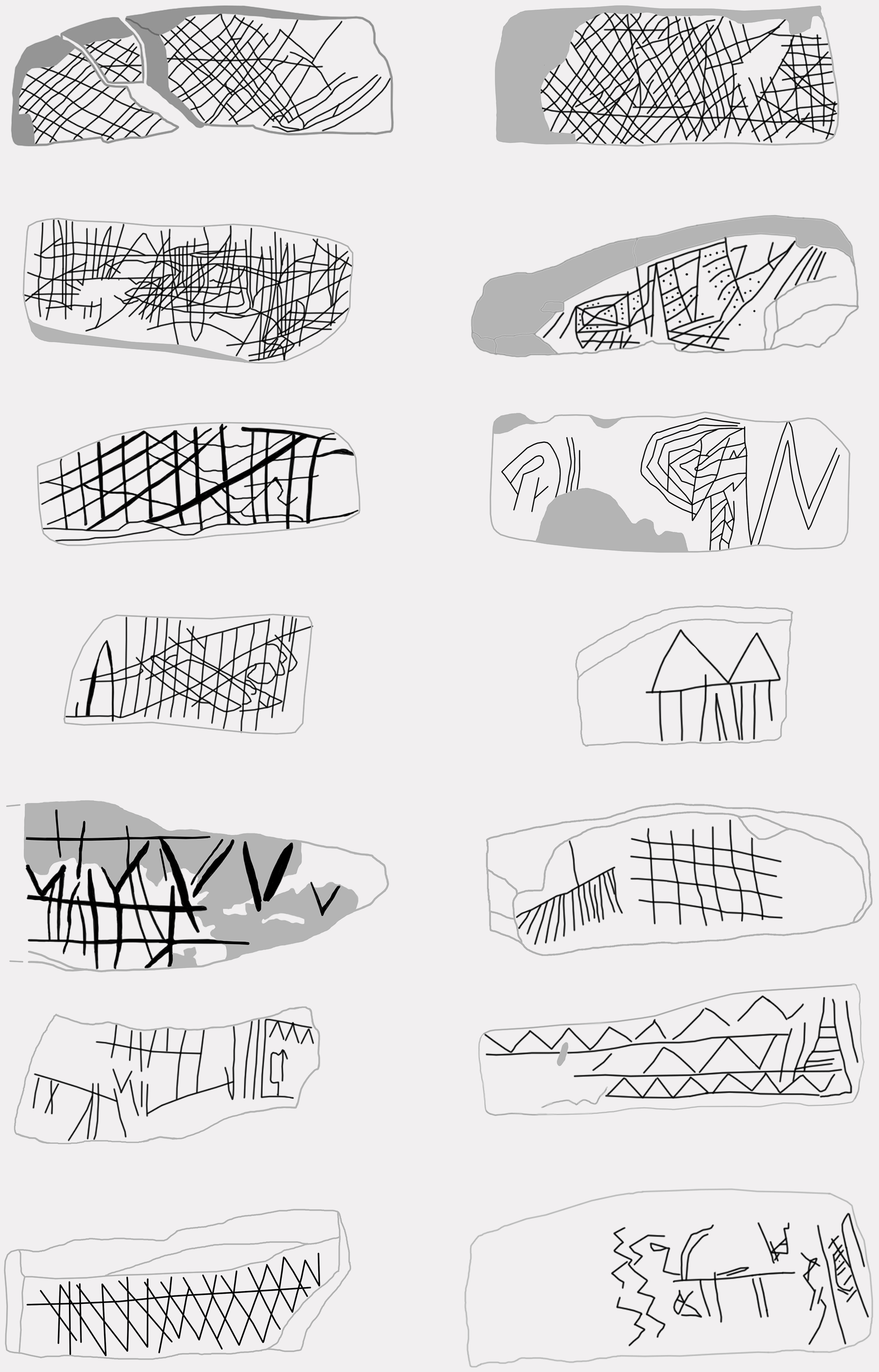

The engravings, linear marks in particular, were discovered (and some rediscovered) on the floor of the rock shelter. After two field campaigns in 2022 and 2023, around 30 graphic units have been recorded. Most of them are located in the southern part, near the edge of the floor, covering a 9 x 6 m area. The size of the engravings varies between 3 to 32 centimetres, and their depth and width range from 0.1 to 0.6 cm. They comprise vertical, horizontal, and diagonal lines which sometimes intersect.

Dating petroglyphs, especially in open-air sites and without secure archaeological or chemical data is difficult. However, various clues suggest a timeframe of the engravings at Mghvimevi. First, the lithic assemblage, despite much of it in “ex situ” context, seems analogous to Upper Palaeolithic lithic collections elsewhere in western Georgia. Second, patches of accumulated chipped stone and split bone on the surface of the floor are overlain by a stalagmite crust suggesting in situ context. Third, comparisons with European Upper Palaeolithic rock art where thousands of linear marks have been identified, such as in northern Spain, France, and Italy, support the proposed age of the linear marks at Mghvimevi. Besides, the closest geographical and thematic analogue to Mghvimevi is the cave site Agtsa in the northwestern part of Georgia where the walls of the cave are covered by non-figurative engravings, similar to those at Mghvimevi, which were considered Upper Palaeolithic.

Khvamli

Khvamli is another location within the Rioni-Kvirila basin where rock art has been observed. Khvamli is a limestone massif situated between the Tskhenistskali and Rioni river gorges. The length of the massif is 11-12 km, and the width is 7 km. The Khvamli massif is of monoclinal structure and is predominantly constructed of Urgonian limestones. Its southern slope is separated from the Okriba massif, composed of Bajocian porphyrites, by a 300-500 m high cliff. The southern part of the northern slope of the Khvamli massif is strongly karstified, characterized by numerous sinkholes, deep cracks and shafts. The northern section of the Khvamli massif is constructed from Upper Cretaceous thin-layered limestones and is weakly karstified (Tielidze 2019).

Khvamli caves are mentioned in numerous historical sources throughout medieval Georgian historiography. There are numerous natural and manmade hollows, where in the medieval ages, people built defensive structures to hide during raids from enemies but more interestingly, according to the legend, Georgian kings kept the treasure there. Building defensive structures in cliffs was a common phenomenon in medieval Georgia. Despite written sources mentioning royal treasure hidden in these caves, archaeological work conducted in 1939, 1945 and 1986 revealed only the remains of hearths and pottery. More importantly, they discovered red-painted figures on the cliff walls, depicting horse raiders and undetermined signs. Based on the various materials, these caves and their paintings are dated to 12th-13th cc AD.

Three rock art sites are discovered in southern Georgia – Trialeti, Zurtaketi, and Damirgaya.

Trialeti

Trialeti is located near the town of Tsalka, at an altitude of 1595 m in the Avdriskhevi River gorge, a tributary of the Khrami River. This area is composed of Late Pleistocene andesite-basalt lava flows, which have produced terraces on both sides of the river gorge.

Within the recorded area, 103 figures are distributed over six panels. They face southwest and represent the vertical and horizontal cliff sections. Incision is the most frequently used technique at the Trialeti rock art site complex. The figurative repertoire of the Trialeti corpus comprises zoomorphic (57 figures), anthropomorphic (6 figures), and geometric (9 figures). Other categories are weapons (bow and arrow) (5 figures), religious signs (cross) (11 figures), abstract (6 figures), and undetermined (9 figures). Panels are 1-2 m long and wide, but some of them reach 5-8 m in length. The figures vary between 2.5 and 20 cm, and the width and depth of incisions are 1-2 mm. The figures on each panel are displayed in various ways: hunting scenes, groups of animals, or isolated figures.

Among 57 zoomorphic images, most depict cervids (18), and equids (6) from various chronological periods. They are followed by camelids (3), caprids (3), birds (1), and hybrid/unreal animals or undetermined genera (26).

In sum, Trialeti plays a crucial role in understanding the local environment, fauna, and geological processes, such as rock varnish deposition. On the other hand, the constant practice of rock art with changing styles and themes throughout the prehistoric and historical periods is noteworthy. Moreover, by analysing the thematic repertoire, it becomes evident that depicting animals, often in the hunting scenes, has been the most common trend at this site. Hence, hunting appears to be one of the main interests, if not the main activity, of prehistoric societies in Trialeti.

Zurtaketi

Zurtaketi is situated approximately 20 km south of the Trialeti rock art site, in the Khrami River basin. It is an alpine plateau that sits over 1400 m above sea level. This area is renowned for its numerous kurgan fields, among which the Zurtaketi Kurgans stand out for the evidence of massive, engraved slabs.

Zurtaketi kurgans vary in size, ranging from 25 m to 100 m in diameter. Their heights also differ, with the smallest being 1.5 m high and the largest reaching 7-8 m in height. Typically, in the center of the construction is a burial chamber of a rectangular shape, built with dry stone walls. Burial chambers have an entrance, known as dromos, and a long paved road, usually directed to the east. The kurgans, based on relative chronology, are dated to circa mid-17th to early-16th centuries BCE.

The most common motifs on these engraved slabs are chaotic intersecting lines, but on some occasions, zoomorphic and geometric figures are observed. The main, largest, and most preserved slab with a well-distinguished engraved surface consists of a zoomorphic figure on top of the slab, with two sections of geometric motifs below it. The lower part represents less organized portrayal of intersecting lines that create a net-like figure. The zoomorphic figure, though schematic, can be considered a cervid due to its antlers. From other slabs, only three more zoomorphic figures are observed, but they appear even more schematic. Geometric motifs are significantly more both in number and variety. They consist of triangles, rhombs, squares, zigzags, etc. On a few occasions, along with geometric motifs, simple house-like figures are depicted on the slabs.

Damirgaya

Damirgaya rock shelter is the easternmost located site within this rock art province. It sits on the northern foothills of the Lesser Caucasus, where Georgia borders with Armenia and Azerbaijan. The geological composition of the surrounding area consists of Jurrasic-Quaternary, terrigenous, carbonated, and volcanogenic deposits. More specifically, the site vicinity is composed of sedimentary and igneous deposits, such as lava breccia, andesite-basalts, and dacites. The study shows that the rock shelter, where figurative images are preserved, emerged after the collapse of the rocky outcrop on top of the ridge, leaving numerous boulders dispersed around. One of these boulders split into two parts after erosion caused by hydrothermal activities, so its core slipped away from the boulder, and a hollowed space was created.

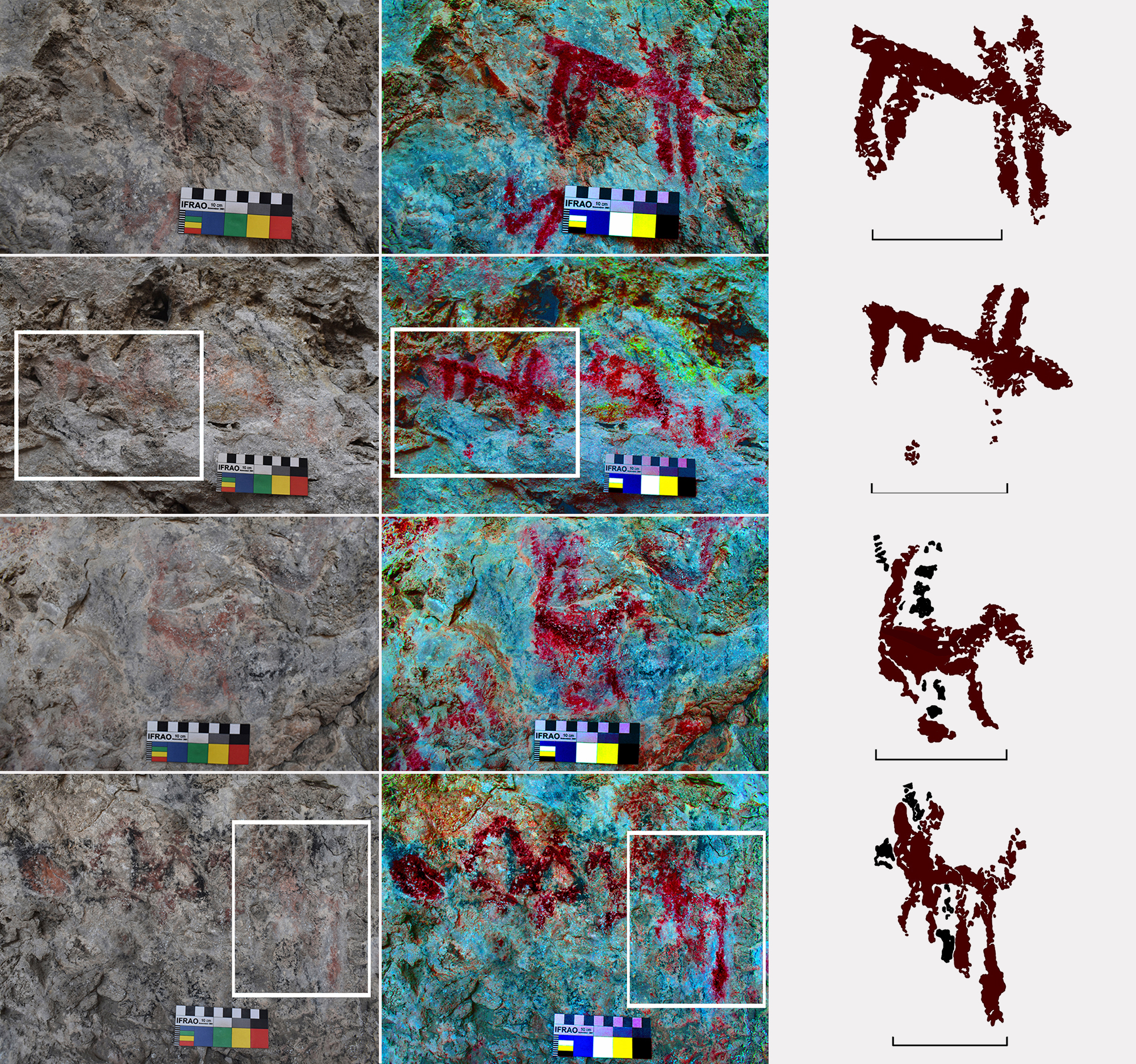

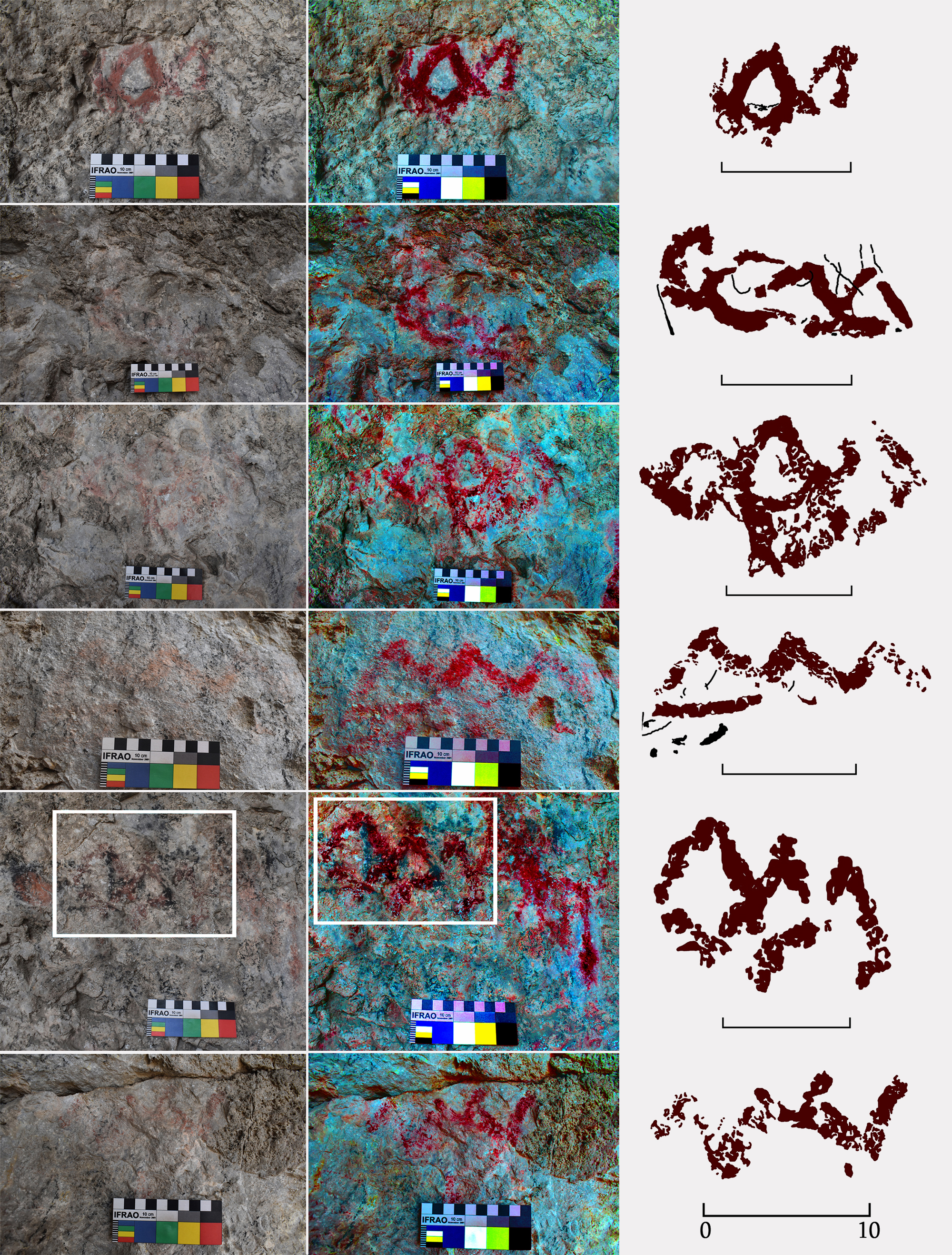

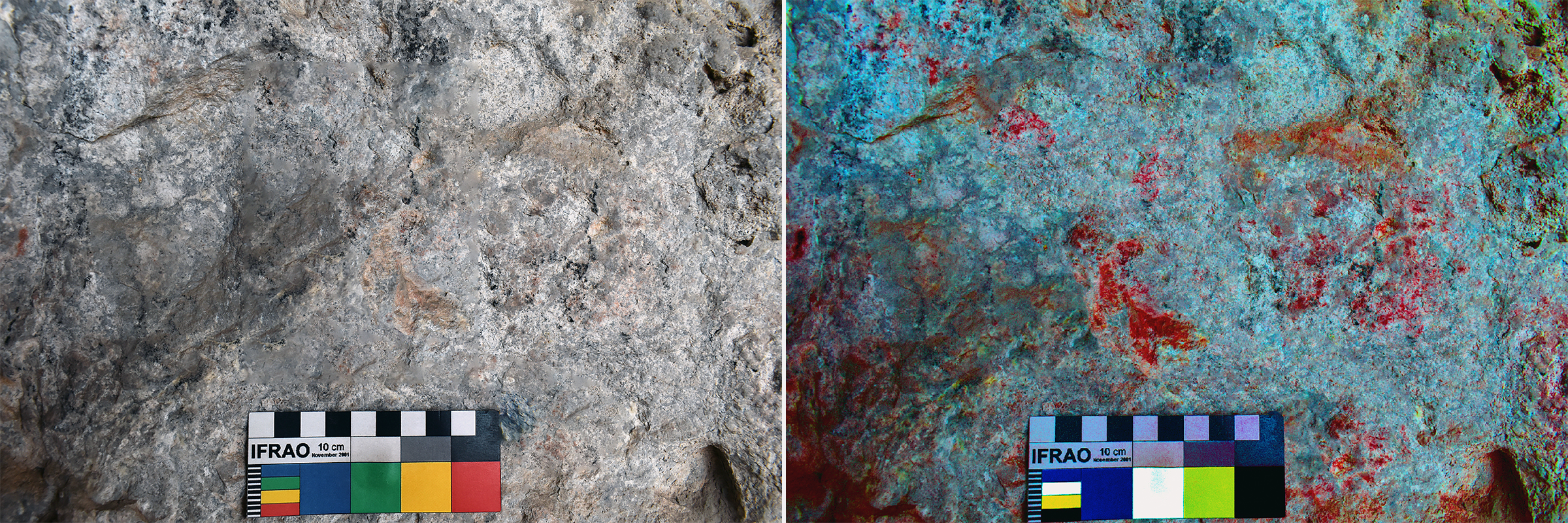

The paintings are located in the interior of the rock shelter. They are quite faded due to weathering and erosion over millennia. Most of them are difficult to identify with the naked eye. In this regard, DStretch was a very useful tool to enhance the red-painted figures. The figures are spread over 3-3.5 m and their dimensions measure between 10 and 20 cm. The figurative repertoire consists of zoomorphic, anthropomorphic, and geometric motifs. Among these motif groups, zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures in particular, are portrayed in a schematic style. Zoomorphic images, though limited in number, include bovids, caprids, and canids.

The study of the figures in the regional context, as well as the archaeological materials originating from the rock shelter, suggests the presumable date of Damirgaya rock art as the Late Neolithic-Chalcolithic period, i.e. 6th-5th millennium BCE. The study also indicates that prehistoric foragers and herders were familiar with the depicted animals, as evidenced in the local fauna of the early and mid-Holocene. Regarding the geometric motifs, connected triangles might be considered depictions of mountains while others such as rhombs and zigzag lines might have pictographic or graphic communication meanings.