In 1881 Cockburn had found fossilised rhinoceros bones in the valley of the Ken River in the Mirzapur region as well as a painting of a rhinoceros hunted by three men in a shelter near Roap Village. In 1881 J Cockburn published an account of all his discoveries (J Cockburn 1891: 91). F Fawcett in the cave of Edakal in Kozhikode district of Kerala made the earliest discoveries of rock engravings (Fawcett F 1901: 402-21). A few years later A Silberrad published a pictorial description of the rock paintings in Banda district (Silberred 1970: 567-70). C W Anderson discovered a painted shelter of Singhanpur in the Raigarh district in Madhaya Pradesh (Anderson CW 1981: 298-306). More rock paintings were found later by F R Allchin 1963: 161) (Sundara A 1974: 21-32) and (K Paddayya 1968: 294-98) from the same area as well as the Gulberga district of Karnataka. Manoranjan Ghosh brought the Adamgarh group of painted rock shelters near Hoshangabad in Madhya Pradesh to light in 1932. The first example of rock engravings was discovered in 1933 by K P Jayaswal in a rock shelter at Vikramkhol in the Sambalpur District of Orrisa. (Jayaswal KP 1933: 58-60).

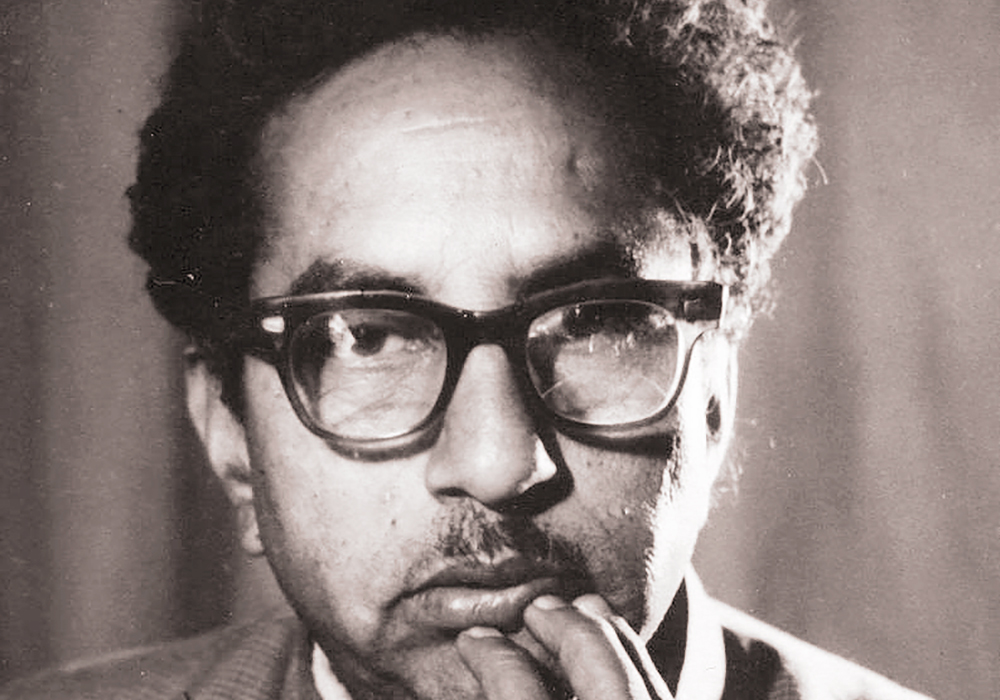

As Dr Jean Clottes said, the ‘Father of Indian Rock Art’ and my (Guru) teacher Dr V S Wakankar had discovered several hundred painted shelters mainly in Central India, and attempted a broad survey of the rock paintings of the whole country and prepared a chronology of the paintings based on the content style and superimposition (Wakankar 1973: 251-353). The most important of his discoveries is Bhimbettka near Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh, which has one of the largest concentrations of rock paintings in India. Bright Allchin has published a study of prehistoric art in 1958. R K Verma in 1964, J Gupta 1967, S K Pandey 1961 and J Jacobson 1970 have also contributed to the discovery of Indian rock art. DH Gordon studied the rock paintings of Pachmarhi in the Mahadeo Hills in 1932. He wrote several papers in Indian and foreign journals and has summarised his views on Indian rock art in his book. (Gordon 1958: 98-17).

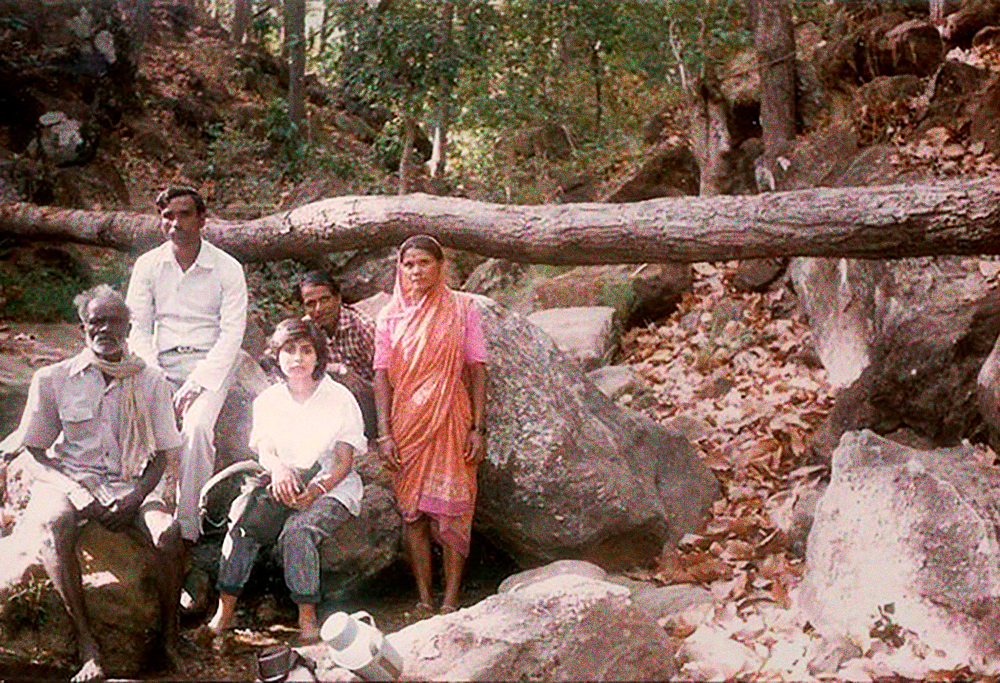

In recent years Yashodhar Mathpal and Erwin Neumayer have discovered a new group of ten painted shelters on Patni Ki Rahari hill near Bari on Bhopal Bareli road (Mathpal 1976 23: 28). In April 1981 to 1990, with the help of local tribes, I discovered fifteen painted rock shelters in the Pachmarhi Hills. In India over a thousand rock shelters containing paintings are situated in more than 150 sites. In India almost every state has rock art sites of painted shelters and engraved boulders.

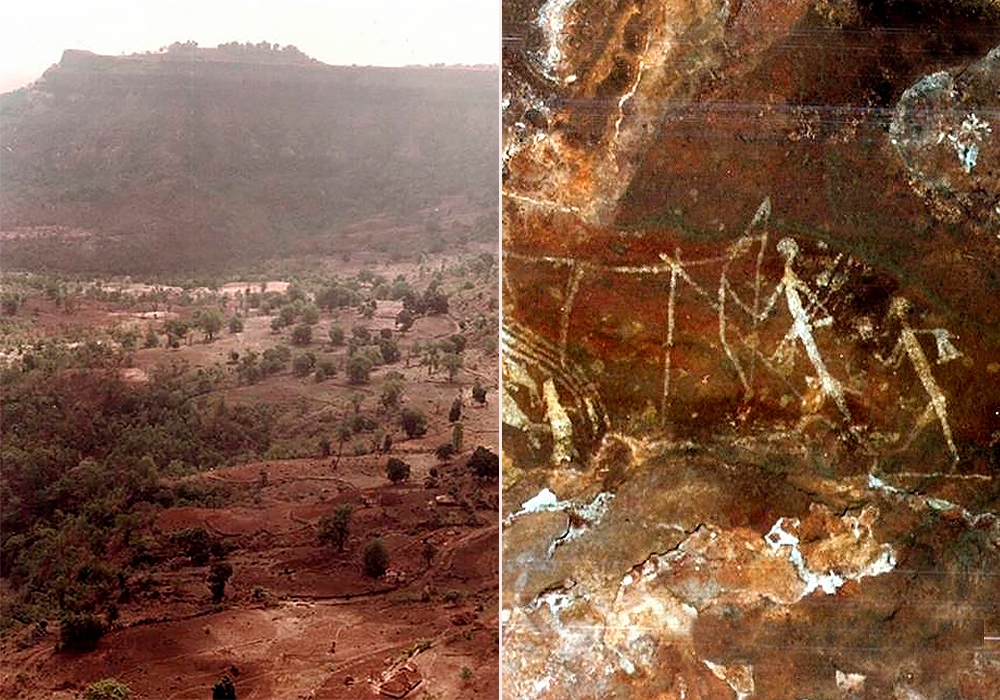

Central India is the richest zone of prehistoric rock art in India. The highest concentration of rock art sites is situated in the Satpura, Vindhya and Kaimur Hills. These hills are formed of sandstones, which weather relatively faster to form rock shelters and caves. They are located in the dense forest and were ecologically ideal for occupation by primitives. They were used for habitation in the Stone Age and even in the later periods. Inside the caves on the walls and ceilings artists painted their favourite animals or human forms, symbols, daily life hunting and fighting.

The Pachmarhi Hills are situated in the geographical center of the Indian sub continent in the State of Madhya Pradesh. The hills lie in the Satpura Range, formed of the Gondwanaland sandstone belonging to the Gondwanaland series of the Talcher Group formations. The sandstone sequence is of the upper Gondwanaland formation. The sandstone is relatively friable and, on weathering, forms the sandy solid found at the foot of the hills. These hills form one of the most beautiful parts of the Satpura Range. The shelters are found all over the hills and the surrounding forests, in the foothills and riverbanks. Many shelters are covered with paintings made over centuries by early inhabitants depicting a wide range of subjects expressed by them in a variety of styles and left as great heritage for us to understand them and appreciate their unique contribution.

Captain J Forsyth made the discovery of this place, as a sanitarium. Forsyth was sent there in 1862 under the instructions of Sir Richard Temple, Commissioner of that day to explore this portion of the Satpura Forest. Here he built a forest lodge and named it “Bison Lodge”. His famous book “The Highlands of Central India” depicts the exquisite beauties of the Satpura range. The point from where Captain J. Forsyth forest glimpsed the extra ordinary sight of Pachmarhi is still one of the finest points named as “Forsyth point”. When he came to Pachmarhi, the area was occupied by the Korku jagirdar of Pachmarhi, but there were traces of a much older civilization in the shape of sites of ruined huts near “Handi kho” site. The total area of the plateau is about 60 sq kms including the forest area and 12.90 sq kms occupied by the Pachmarhi cantonment.

Part of Forsyth’s report states “Every where the massive group of trees and park like scenery strikes the eye and the greenery of glades and wild flowers, unseen at lower elevation, maintains the illusion that the scene is a bit out of our temperate zone. Thereafter, a multitude of beauty spots were discovered, and the place developed. Much remains the same even today. Pachmarhi still retains its tranquility, its many silences, its gentle green and its soothing forest. It is one place where solitude is miraculously achieved in moments, and the sighs of swaying trees are the only sounds you will hear. Pachmarhi is a lovely hill-girded plateau on the green Satpura range, called by the tourists as the Queen of Satpura." (M.P. Tourists 1962: 4).

By popular belief the name “Pachmarhi” is a derivation of “Pach-marhi” or a complex of five caves of the Pandava brothers, who are supposed to have spent a considerable portion of their lifetime of exile incognito in this area. Genuine place is attainable any where in “Pachmarhi”. Pachmarhi, the legend tells, was once a huge lake guarded by a monstrous serpent. This serpent began terrorizing the pilgrims visiting the sacred shrines of the Mahadeo hills. Lord Shiva, angered by this, hurled his trident at the snake, imprisoning him in the rift of a solid rock, which assumed the shape of a pot or handi. The flames of wrath dried up the lake and empty space assumed the shape of a saucer. Botanists have therefore reported the existence of plants only found by the sides of large expanses of water, these rare penmen of flora seem to bear out the myth! (M P Tourist 74:2).

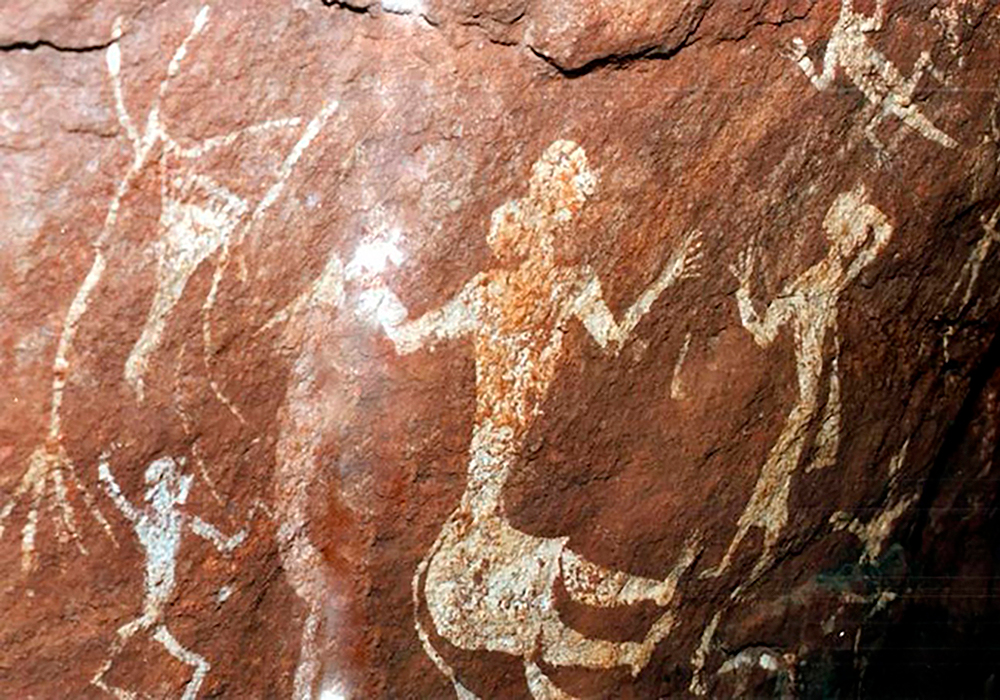

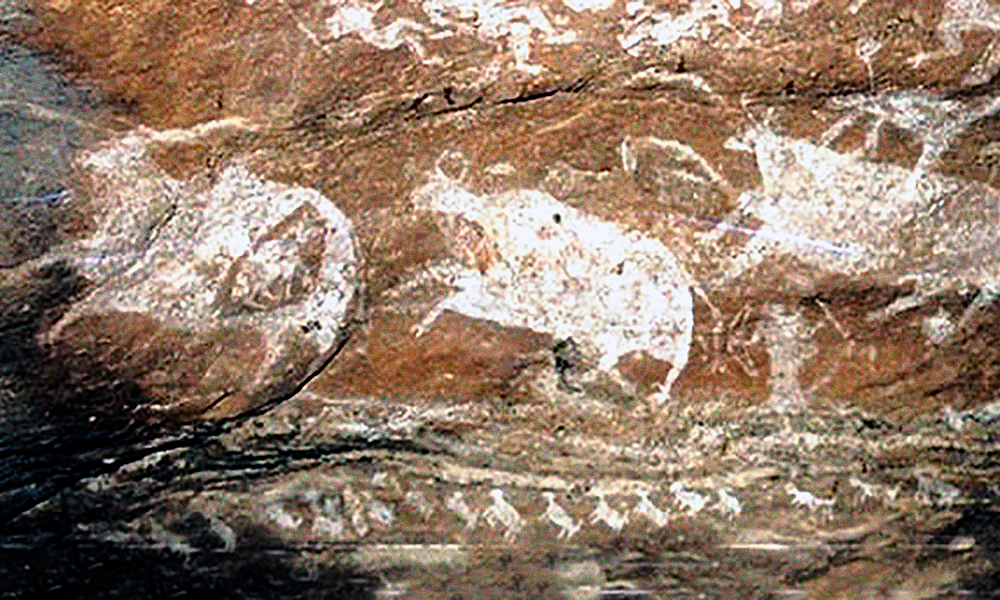

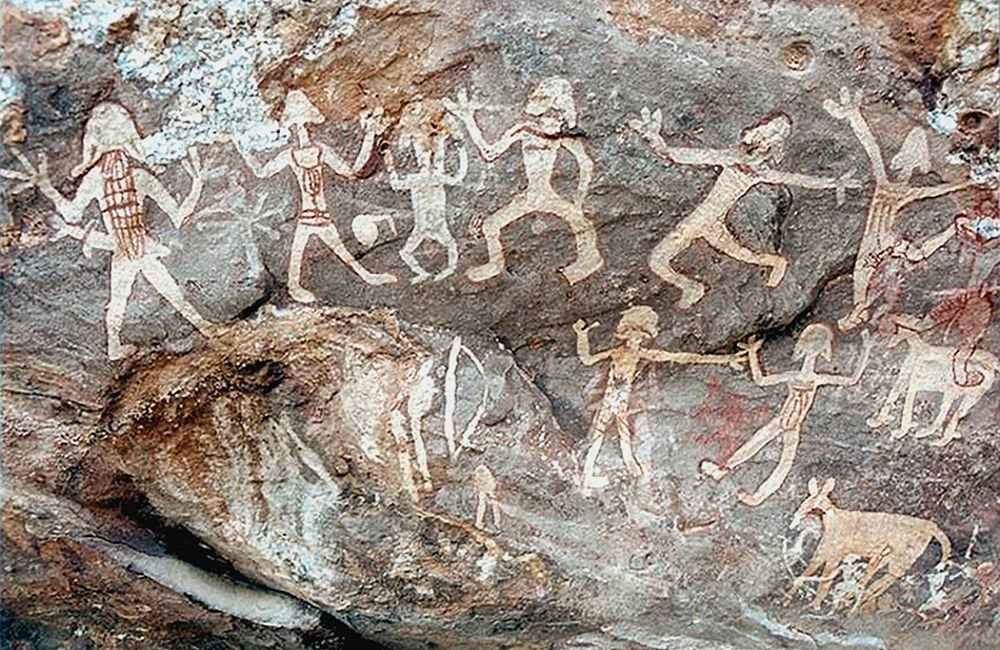

GR Hunter brought the painted rock shelters of Pachmarhi Hills to the notice of D.H. Gordon (1958). Hunter had excavated some sites here in 1932 and again in 1934-35. The 1935 excavation revealed that the cultural sequence within this region commenced during the Mesolithic period, confirming that the Pachmarhi Hills were not occupied during the Palaeolithic. Thus, the rock paintings of this region belong to the Mesolithic and later periods. The Mesolithic paintings clearly depict a society of hunters and gatherers. Mainly they portray man and his relationship with animals. The subject matter of this period is quite varied, although game animals are most frequently represented. Bulls, bison, elephants, wild boars, deer, tigers, buffaloes, dogs, monkeys and crocodiles appear alongside smaller species such as rats, lizards, turtles and fishes. Some of the birds are identified as peacocks, jungle fowl and ostrich. Arthropods, such as scorpions and wild bees, were also depicted. The hunters are portrayed using spears, axes, sticks and bows and arrows.

Female figures are occasionally shown. Sexual life does have a place in Mesolithic art but is not very prominent, and male and female union is rarely shown. It seems that dances were important for ceremonial or entertainment purposes during this period. For these dances headdresses and animal masks representing donkeys, crocodiles, bulls or monkeys were worn. The compositional elements of these Mesolithic paintings are highly developed. They represent an element of the creative spirit of the early people. That their aesthetic sense had developed to a high degree can be seen in geometric designs and in paintings of the X-ray style. Pregnant animals such as cow and deer depict the fetus in the womb. Most interesting depiction is a urinating cow. It suggests the awareness of medicinal value of cow urine to the primitives. As we all know according to Indian Ayurved cow urine is a very good treatment for cancer patients and for other ailments. Head Hunters are another interesting depiction . A variety of animals can be seen from elephants to ants.

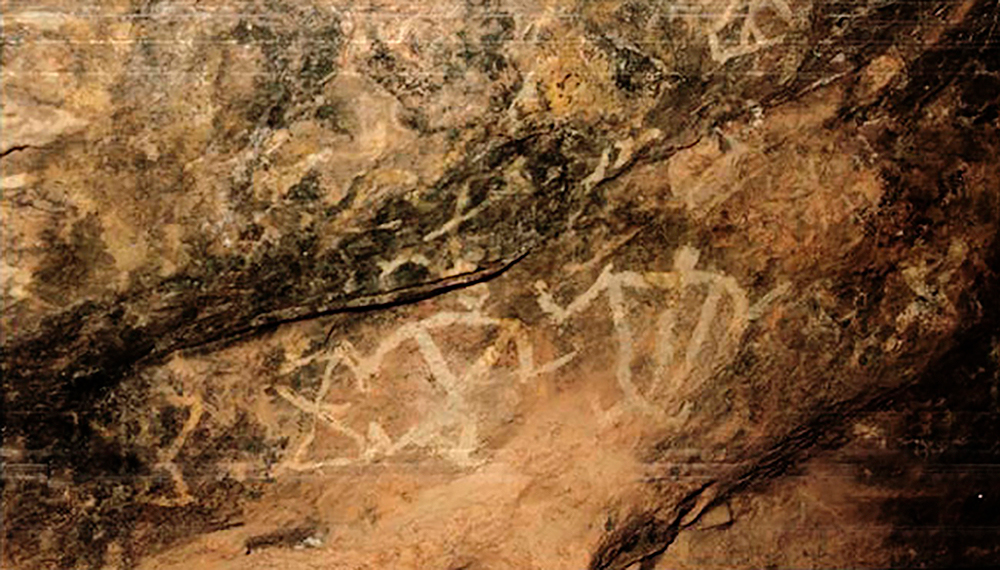

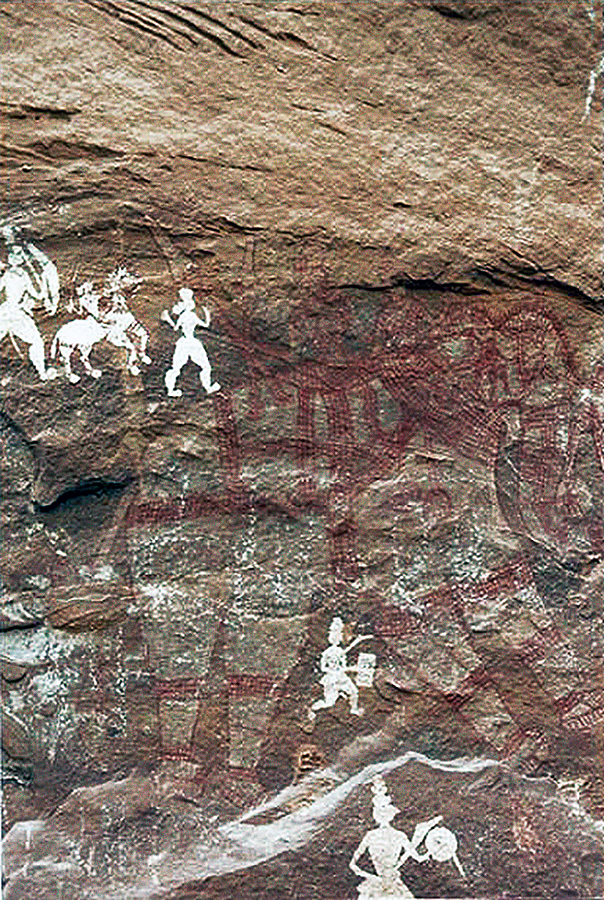

In the Pachmarhi Hills most of the paintings are from the Chalcolithic to the Historical period. Conflict is one of the main themes depicted during this time. War scenes are common but reasons for conflict are not indicated. Horsemen armed with swords and shields overlie the earlier paintings portraying the life of hunters and gatherers. They bear elaborate war equipment consisting of spears, axes, swords, shields, daggers and bows and arrows. Other individuals carry drums and trumpets, and foot soldiers as well as men riding caparisoned horses and elephants are depicted. Goats, dogs, oxen, donkeys and performing monkeys accompany the troops. The descendants of the original hunters and gatherers and artists of this region are the tribal Korku and Gond who still uphold some of the traditions of their ancestors. In the rock paintings their ancestors are depicted dancing in pairs or in rows and playing musical instruments. They hunted animals and collected honey from the hives of wild bees. Their mode of dress was quite simple. The women carried food and water and looked after the children. The forebearers of the present day tribal people had a variety of ways to express the magic of their beliefs, rituals and taboos. The tribes living in these hills have wooden memorial boards on which the carved horse and its rider is similar to those painted by their predecessors in the past on the walls of their rock shelters . They also decorate the walls of their houses and this activity seems to have its roots in the cave dwelling traditions of their ancestors. Men and horses of geometric construction are randomly spaced across the walls. Such paintings are done during the rainy season and on festive occasions, and bear a close resemblance to those found in the painted shelters.

Presently, the wall paintings in their houses, as in the great majority of rock paintings, are executed in red and yellow pigments prepared from hematite or other iron oxides. The white pigment was made from limestone or kaolin, while mixtures of pigment that produce pinks are also found used in paintings. The rock paintings were executed in a number of stylistic conventions. Some are only sketches or constructs of lines, while others are silhouettes filled with colours and embellished with decorative designs.

Considerable information is now available about the antiquity of Pachmarhi from Archaeological sources. The excavation by archaeologists in different shelters has provided sufficient archaeological data of the people who occupied these shelters. Excavations were conducted in rock shelters since 1932 by GR Hunter. He introduced the cave art of Pachmarhi in his lecture before the congress of the pre-proto historic science in 1932, which brought the painted rock shelters of Pachmarhi Hills to the notice of Lt Col DH Gordon. Hunter excavated here in 1932 and 1934-35 (Hunter-1955).

Clear evidence of Mesolithic culture has come from the Dorothy Deep shelter. The 1932 excavation was confined to the Nallah area, and a trial pit close to the rock wall up to 2’ and the 1934 excavation by a trial trench right across the breadth of the cave up to 5’ depth with undisturbed stratification. The earliest deposit was of the Mesolithic (Tardenoisian) period. The multiplicity of shapes and sizes, characteristic of most stone age cultures, suggests occupation prior to the Neolithic and the metal ages. Subsequently, the shelter was occupied by a culture using pottery. The excavator thought that though there was no sterile deposit between the two cultures, and quartz flakes were found in the upper layers where pottery abounds. It was doubtful if there was any overlap.

Three skeletons were found in association with the typical Tardenoisian flakes and implements but without any beads or other objects. Only two small pieces of cranium were found to be intact. Thus the following sequence has been worked out:

The excavation of 1935 followed the above sequence and attempted to establish the inference that the Palaeolithic man never inhabited the Mahadeo Hills. Divisible into three sub phases - upper, middle and lower. There was a definite cultural development during the Mesolithic age, in the technique of flaking, leading to the evolution of patterns more suited to the purpose. These tools are similar to those recovered from the Tardenoisian and Caspian sites in Europe and Africa (M.D. Khare 1984; 130). In 1950 A. Ghosh excavated Baniya Berry shelter where a trench of 22”X39” was dug and four layers were found. The lowest consisted of weathered sandstones and yielded no finds. Layer 3 - yellow brown soil mixed with stone chips, geometric microliths, pre pottery period. Layer 2 - of similar soil, also yielded geometric microliths. Layer 1 - top layer dark brown earth, no tools. This suggests the shelter was inhabited only during the Mesolithic period.

Then S K Pandey excavated two rock shelters in 1968. The first shelter was Jambu Dweep in which digging was barely 6 inches deep. It yielded small numbers both of microliths and pottery shreds. Another shelter, Baniya Berry, the excavation was in two distinct layers. The lower layer had loose sandy soil, with one large chalcedony piece, 2 Jasper flakes, 2 triangles and 28 chips. The upper layer of brown earth produced fluted cores and 4 parallel one-sided flakes. There was no pottery in this shelter.

During my field research work in the year 1990-91, I collected some Mesolithic pottery shreds, a few tiny pieces of bone and a pendent of the tooth of an herbivorous animal (monkey) from the loose surface of the shelters. Total finding of microliths: Trapeze - 1, blades - 34, side scraper - 8, and burins - 2.

Mesolithic technology, introduced from outside, supplemented the older technology with the passage of time. It consists of Mesolithic tools made of slender micro blade, which were first detached from cylindrical cores by a pressure technique and then blunted on one or more margins. These tools, made of fine-grained rocks, lime, chert and chalcedony, comprise blunted back blades, obliquely truncated bladed, points, crescents triangles and trapezes. By hafting them into bone or wooden handles, these tiny tools were utilized to make knives, arrowheads, spear heads and sickles. Colour nodules are also found in the loose surface. Yellow colour nodules have been found in Bori shelter.

The gradual developments of changes can be seen in this area regarding the use of fire and construction of floors of stone slabs. In the later phases the appearance of copper tools and pottery suggests contact between the Mesolithic people of shelters and Chalcolithic people of the plains. In the upper most layers, early historic pottery shows the persistence of Mesolithic way of life up to the historic times.

The population of Pachmarhi is principally tribal. The main tribes are Korku and Gond. The four-sub caste of Korku is Muwasi, Bawaria, Ruma and Bondoya. The word Korku means simple men or ‘tribesmen’. (Koru meaning 'man' and ku its plural). According to Korku, traditions of their origin, on the request of Ravana, Lord Mahadeo created two images of a man and woman from the clay of an anthill. He then infused life into these figures and they were called ‘Mula’ and ‘Mulai’, with a common surnames Pathre. These two were the ancestors of the Korku tribe. Korku are a Munda or Colarian tribe as their language belongs to the Mundari of Austro-Asiatic family. The Gond tribes speak Gondi language. The Gonds also call themselves ‘Ravanvasi’, meaning descendants of Ravana king of Lanka. Their legends suggest that they have migrated to the area from Andhra in the medieval period, and they speak a Dravidian language called Gondi. The Korkus consider themselves superior to Gonds. They would not take food from Gonds, but would not refused water and chilam (cigar).

The average Korkus are well built & muscular. They have a round face, a nose rather wide, prominent cheekbone, a scanty mustache and his head shaved after the Hindu fashion. They are slightly taller than Gond (Russel and Hiralal 1969 : 552). They make houses of wattle and daub and with roofs made of handmade, baked clay tiles. The locals generally sleep on the ground and a few low stools carved from teak wood serve them as pillows. There is generally a verandah in the front of the house, a cattle shed attached to the side. The villages are kept remarkably clean.The interior of the house in Korku village is kept clean. The walls are decorated with various designs drawn on festive occasion, and the villagers take delight in pasting coloured pictures on the interior walls of their hut for decoration. Every villager has a few pigs and fowls about and both of which are eaten after being sacrificed. They are by no means particular about what they eat, fowls, fish, crabs and tortoise all consumed. Bondoya korku eat buffaloes too. The millets (kodu - kutki) are grown principally in the hilly tracks of trivial inhabitant, which form the staple food. Tobacco smoking and country liquor made by the local mahua flower is very common among these aboriginals. They often supplement their food with a number of edible fruits, tubers and honey collected from the forest. The tribal economy depends on agriculture.

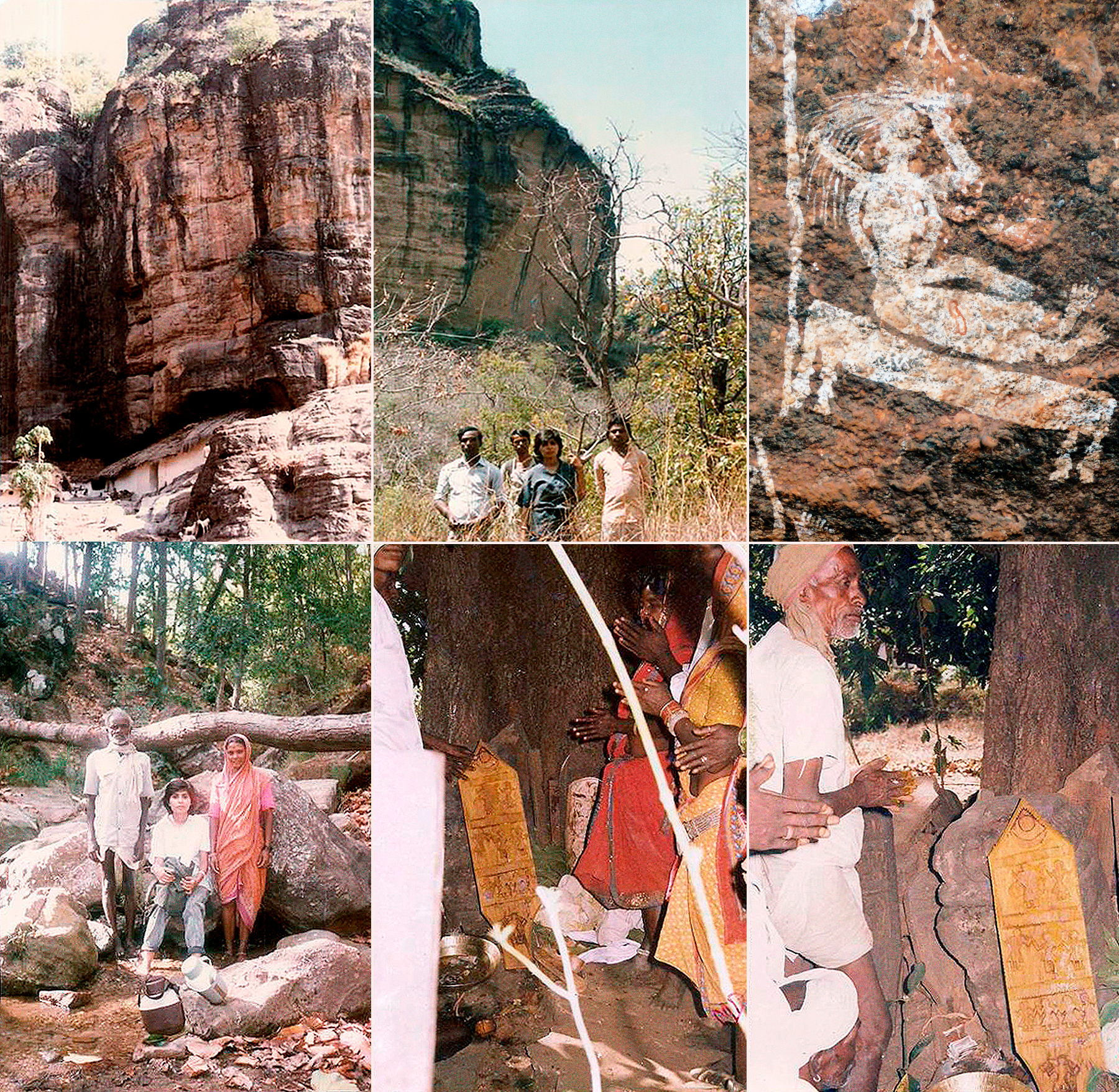

Like most hill tribes the korku are remarkably honest and truthful. Korku consider themselves to be Hindus, and are held to have a better claim to a place in the social structure of Hinduism than most of the other forest tribes. They worship the Sun, Moon and also Mahadeo. The main festivals among Korku tribe are Shivaratri and Nagapanchami. Pachmarhi is the important pilgrim center for Shivaratri and Nagapanchami fares. The priests of Korku are of two kinds: ‘Parihars’ and Bhumka’. The Pariahs may be any man who is visited with the divine afflatus or selected as a mouthpiece by the deity. Parihars are also rare, but every village has it Bhumka, who perform the regular sacrifices to the village gods and the special ones entailed by disease or other calamities. The Korku have some belief in sympathetic magic as other primitive people. They also trust in Omens.Korku tribe also has funeral rites. The dead are usually buried, the head pointing to the south. The earth is mixed with thorns while being filled in so as to keep off hyenas and stones are placed over the grave. Their family members and relatives honor the dead with carved and decorated teak wood memorial boards, placed under a sacred tree in the memory of the deceased during a highly religious ceremony. The primitive men in Hoshangabad district used painting as the chief source of amusement. Pachmarhi and Adamgarh hillock is the living monument of their art. The times have changed and there is a variety of means of amusement available to the people now.

In the remote mountains, deep dense forests, swamps and deserts the lives of hunters and gatherer remained almost undisturbed, long after more advanced cultures settled in the valleys and lowlands. The tribal people living in the rock shelters observed the colonizing groups and recorded their activities in paintings on the walls of their rock shelters. Later, they were to adopt from the newcomers only few basic cultural items. This is the most complete record, supported by the evidence of archaeological remains, of the tribal culture, as it existed in the past.

Following this the carved boards are venerated and wept over. Later, a goat or jungle fowl is sacrificed and eaten, while the local liquor made from the flowers of the Mahua tree (Bassia latifolia) is consumed. One such sacred tree is situated in the “Gond Baba Udhayan” (lit. - Garden of the Gond deity) located in the Pachmarhi town itself. Tribal people who come from the surrounding villages of Pachmarhi use this site for their religious rituals followed by feasts. Memorial boards are placed at the base of the sacred tree within ten years of a death. The subjects carved into the board are selected form a limited list of elements. These are usually horse riders; group of geometrical human figures holding hands, and representations of sun or moon and the name of the deceased.

In carvings of the horse and its rider the Korku do not depict their own ancestors, as they did not have horses. The figures mounted on horse represent their conquerors. This element of the carving is totally unrelated to the loves of the deceased, but its stylistic form and that of other human figures is similar to the more recent rock paintings situated in rock shelters only a few kilometers away (Wakankar and Brooks 1976: 16).

Many of the present day tribal communities decorate the walls of their house with paintings. The selected subjects relate to their natural and cultural environments, depicting birds, floral patterns, whilst other appears to be of symbolic or ritual importance. These wall paintings also seem to have their roots in the rock art tradition. At present the Korku tribal live in wattle huts whose walls are coated by clay colored white. The tradition of paintings continues as the korku women decorated their house walls with paintings and sketches. They use local colour such as the dark or Indian red, yellow ochre, blue and white. The paintings are executed during the slack rainy season or occasionally during festival events. The women in the Korku society carry out all domestic work and look after the children.

The depiction of a peacock on the wall of a hut in the Kajri village situated 35 kilometers from Pachmarhi town is very similar to rock paintings found recently in the Langi Hill shelter . A symbol painted on the same repaired wall closely resembles a rock painting of the Swem Aam shelter that has only been recently explored. That the two traditions share the same roots can be seen in the common subject matter and the continuing stylistic conventions displayed by the contemporary art.

The subject matter in rock art can be very varied. The main subject everywhere is the animal or scenes of hunting them, which is the most common subject of rock paintings belonging to the Mesolithic and later periods. The subject matter of rock paintings also helps in studying many facets of human life. "The depictions of the species of animals, human and the food gatherers tell us much about the ecosystem in which they lived. The depiction of weapons, tools and other implements reveal their technical abilities. The illustration of his myths and beliefs bring back to our consciousness the essential aspects of out intellectual roots and displays the existential relationship between man, nature and the supernatural" (Anati-1980-20).

In the Indian rock paintings the presentation of man and animals is of almost the same standard although stylistically there are many differences (Mathpal 1980- 93). The artist did not represent everything he saw or knew. Besides animals and their hunters, there are other subjects depicted in rock art via social and cultural activities, ritual performances, domestic life and different images of women, such as mother with a child. In the early period human figures are rarely painted and the depiction is only symbolic and stick-shaped. Many human figures are conical animalized (Gordon 1960- 512), grotesque (Breuil and Lantier 1965- 187) and disproportionate (Bernguer 1973:40?45). In the rock paintings of Pachmarhi Hills prehistoric artists had depicted many cultural dimensions of their life and surroundings. Artists of early and later periods were greatly interested in the depiction of ritual dance and music. In the later period different types of musical instruments, battle scenes, soldiers, horse riders, symbols, patterns etc depicted them. The subject matter of the rock painting of Pachmarhi has been divided into the following categories: -

(a) Human forms. (b) Animal forms. (c) Scenes. (d) Material culture. (e) Mythology. (f) Nature. (g) Inscriptions.

HUMAN FORMS

Human beings are painted lesser realistically than the animals. There are total 2449 human forms belonging to all the periods in Pachmarhi. These forms have been divided into the following 30 sub-groups according to the subject matter: -

(a) Man. (b) Women. (c) Boy. (d) Girl. (e) Infant. (f) Hunter. (g) Fighter. (h) Rider. (i) Attendant. (j) Dancer. (k) Drummer. (l) Pipe Player. (m) Harp Player. (n) Cymbal Player. (o) Man with Mask. (p) Man with Kanvar. (q) Man with animal hide. (r) Women with sickle. (s) Man with axe or (Tree cutter). (t) Honey Collector. (u) Ritual performer. (v) Head Hunter. (w) Leader. (x) Mother Goddess. (y) Copulation. (z) Man in Hut. (aa) Anthropomorphic. (ab) Women engaged in domestic chores. (ac) Pregnant Women. (ae) Fragmented Figures.

ANIMAL FORMS

Normally animal forms part of a hunting scene. A good number of the large or medium size animal’s figures have been painted naturalistically. The common most details are their horns, snout and ears. The animal drawings of early period are very natural and more realistic than those belonging to the later period. In the earliest period the animals were depicted in considerable size, beautifully decorated with abstract and geometric patterns. There are nearly 1008 images of animals belonging to 25 different species. These species comprise Tiger, Leopard, Elephant, Wild buffalos, Bison, Oxen, Cow, Nilgai, Sambhar, Swamp deer, Wild boar, hyena, wolf Dog, Monkey, Horse, Pangolin, crocodile and probably a giraffe like long necked animal. Drawing of Porcupine, Rabbit and small creatures like Lizard, Scorpion and Fish are also found. Drawings of birds such as jungle fowl, peafowl and some ostrich like unidentified birds are also recorded. Some depiction of insects like centipedes and honeybees has also been found.

BIRDS

Total 37 drawings of a limited variety of birds have been found in various shelters in Pachmarhi Probably birds did not form major part of food but only an object of entertainment and curiosity in their surroundings and thus did not receive much significance in the lives of pre-historic men.

MISCELLANEOUS

Different types of fish, turtles, scorpions, lizards, insects like centipede and honey bees have been depicted in different shelters.

SCENES

Prehistoric artists have drawn all aspects of their life independently and complete in it. The artists depicted various compositions on the rock surface. Such compositions usually comprise scenes of hunting, food gathering, fighting, dancing, and music, social and daily chores.

MATERIAL CULTURE - HEAD HUNTING SCENES

The subject of head hunting in the history of rock art is very uncommon. At present, in Indian rock painting its only the rock art of Pachmarhi which contain this unique depiction of head hunting. Peru in South America is the only other so far known place where scenes of head hunting are found (Bednarick 1989:73).

There are a total of seven depictions of headhunters, which have been first recorded by me. Executed in bichrome colour, these depictions belong to the historic period. The acts in these scenes depict the brutality prevalent in the society of the Stone Age man. The head hunting scene is very prominent in Lanji Hill shelter wherein a human figure is holding a human head in his right hand and shown running, yet looking back over his shoulder, perhaps anticipating a chase or ensuring himself of breaking contact with his enemy. A giant and robust figure measuring 3 ft in length and 2.5 ft in width executed in light red colour has been depicted which makes everyone curious . A headhunter with identical description as stated above, has been recorded at Swem Aam shelter.

In yet another depiction at Nagdwari shelter a headhunter decorated in red lines, perhaps his tattoo marks, has been shown carrying a well-dressed severed head . At Rajat Prapat shelter four human figures have been depicted as headhunters running in the same direction but at different distances. Drawn rhythmically and full of action, this scene is eye catching and gives an insight into the historic life.

Remarkably, all the drawings of headhunters are filled with white colour and outlined with red colour. The figures have sharp facial features and body proportionate. Headhunters were probably most respected perhaps because they ensured protection of the clan, group or community and achieved victory over their enemies. Hence, the figures of headhunters are often found well decorated with headdress, crown, earrings and bodies covered from waist downwards up to the knees. Every figure holds a severed head, which is well decorated with crown, earrings, headdress identical to its hunter, running in the same direction and same of fashion looking back over the shoulder. The act of beheading human beings was perhaps not a ritual as nowhere in the shelters any such scene has been depicted. It may be assumed considering the prevalent brutality that beheading may be a form of severe punishment to those who committed a heinous crime of transgressing the law of the land of the tribes. However, it is quite likely that the head of the enemy was severed to ensure annihilation and carried back home to confirm victory to own ground, clan etc. and displayed as a war trophy.

Indian history is replete with the instances of human sacrifice prevalent amongst the tribes in the country, particularly, by Gond and Korku tribes. The tradition of human sacrifice was alive in Mahadeo Hill. “In the days that are forgotten, human victims hurled themselves over the rock as sacrifice to the goddess Kali and Kal Bhairav, the consort and son of Shiva, the destroyer”. Capt J Forsyth has mentioned about an eyewitness account of an incident of human sacrifice at Mahadeo Hills in his famous book “The Highlands of Central India” (Forsyth J 1889:180-184).

MYTHOLOGICAL SCENES

The rock art suggestive of mythological origin is that of tree worship, cross worship, symbols of mother Goddess and demons. Gordon has commented that only a few Indian rock art paintings have a religious significance (Gordon 1958:109). “Symbols and so called signs found in rock paintings in different parts of the world are difficult to decipher. It is a code we have been unable to crack”, says Benerguer referring to European Ice Age symbols (Benerguer 1973:73). The paintings of Pachmarhi, which are likely to be related to mythology, have been grouped as follows:

1. Mother Goddess 2. Tree Worship 3. Symbol 4. Cross Worship 5. Swastika 6. Labyrinth (chakra) 7. Geometrical figures 8. Superhuman or deity worship 9. Demons 10. Mythical Animals

INSCRIPTIONS

Writing of inscriptions on the walls of the caves and shelters is associated with Hermits and Monks living in isolation in early historic times. It was common practice in many hills and forest area inhabited by Hermits. These inscriptions do help us place paintings of historic period to certain chronological order. Two inscriptions both in Nagri script in Pachmarhi have been recorded. One is in Dorothy Deep and the other is in Mahadeo shelter. The inscriptions in Mahadeo are too faded to be translated but the inscriptions at Dorothy Deep are by far the most legible. It consists of two lines written in cremish white colour. The first line is obviously meant to be same as commencement of much longer second like. It would appear to be from Nagri of probably 11th to 12th centuries. The translation, which does not make any sense, is as follows: "Lenamasiya a vri vri Dha Dha Ve She Jai Jai".

The Stone Age man has painted many aspects regarding the social, cultural, economical, religious and ritualistic, pertaining to his life on the bare and uneven rock surface. The surfaces in the caves and shelters have been formed naturally over a period of time. The depictions of contemporary flora fauna and domestic activities have also found their places in these paintings. The antiquity of these unique paintings was probably realised first time by Archibald and Carlleyle in 1867-68 when they discovered the first rock paintings in India at Sohagighat in Uttar Pradesh. Mainly amateurs have brought approximately 150 sites of the rock paintings to our attention. The archeologists never seem to appreciate the antiquity of these paintings. Hence due to lack of attention, this national heritage of our country is now subjected to vandalism. It is pathetic to see at some places where those paintings are near extinction due to lack of protective measures. The shelters in Pachmarhi are well known from tourist and archaeological points of view. But their historic, cultural, artistic, musical and dimensional aspects have been left uncovered totally by most of the researchers known to have worked here. Unlike in Bhimbetka, there are numerous shelters and painted shelters scattered all over the Pachmarhi Hills. The approaches to many shelters are difficult, dangerous and time consuming.

Considering Pachmarhi town as the hub there is hardly any direction where the paintings are not evident. The painted shelters are also found in the outer periphery of the Pachmarhi Hills in the Satpura ranges. The study of these shelters has not been done in my work; however, some references of these have been made here and there. I feel a separate study in a different time frame is needed for the detail study of such paintings. Therefore, I have confined my study to the painted rock shelters of Pachmarhi Hills only. I am hopeful that this work will be an authentic record of the paintings of Pachmarhi hills for the students of the rock art in the future. The present study is the first comprehensive and exhaustive record encompassing thematic and stylistic analysis of the rock paintings of Pachmarhi Hills.

METHODOLOGY

The freehand drawings of the rock painting are the most popular method amongst the Indian scholars. But these kinds of drawings or copies can never be accurate and authentic, hence unsuitable for a scientific study. Such reproductions do not provide us the actual size of the form and scale for reduction or enlargements. Even a line drawing made in this way (reproduction without the colour scheme) cannot do justice to a coloured figure drawn on the shelter. Only a few drawings have been recorded to show the details of their features and ornaments etc. Photography is also a very common method for recording the rock paintings. It is an authentic and trustworthy method. The scholars like Leroi Gourhan (1968) have used basically coloured photographic reproduction of South Western European Cave paintings. Marshack (1975:64-89) has also used the special technique of extra close-up, ultra violet and infrared photography for his work. The photography has not been able to avoid the scratching and writing by vandals on the paintings. Many of the paintings are faded to varying degrees because of their age and prolonged exposure to the natural agencies. Therefore such paintings cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by photography. (Mathpal 1984 :4) Brooks (1975 : 92 :97) has evolved another process of reproducing Indian rock paintings. He first prepares a coloured transparency of the original paintings and makes a line drawing from it by projecting the transparency on the paper. After filling the drawing with colours he prepares a fresh transparency by superimposing the projection of the earlier transparency on the coloured drawing.

Today, the method for the reproduction of the rock painting followed is the combination of three means, tracing for dimensions, photography for colour effect and video recording. Tracing method applied by me to reproduce the rock paintings of Pachmarhi hills is not new. Nearly all the art of the Ice Age as well as the later period in Europe and Africa has been reproduced by this method (Cooks, 1961: 61-65, Vinicombe, 1966: 559 - 60). In India also J Cockburn, Manoranjan Ghosh, D.H. Gordon, V.S. Wakankar and Y Mathpal have employed the direct tracing method. In this method, the figure on the rock surface was first traced on fine transparent sheet. The reverse of the tracing paper was then rubbed with a lead Pencil to serve as carbon paper. The traced drawing was then transferred on the drawing paper. The figure on drawing paper was carefully compared with the original paintings on the rock surface to eliminate errors caused in tracing due to the uneven and rough surface of the rock. The drawing was than coloured on the spot continuously observing the tones and the shades of the original. The natural background of the painting was also reproduced in the same way. This method has been followed only in some paintings of the rock shelters, which are easily approachable and located nearer the town. The area of Pachmarhi hills is still one of the most inaccessible parts of India (Wakankar and Brooks 1975: 103). Shelters are spread all over in the dense forest. The shelters are 10 to 30 kms away from the town. This process was not found practicable at every place because the nature of terrain, constraint of the time and danger of the wild life.

The author has done the maximum recording of the rock paintings by the photography method using both coloured films and transparencies. This gives accurate sizes and originality of colours. Infact about the colours you cannot say the present colour tone is as original as it was about ten thousand years ago. Because of the natural weathering paintings are getting faded gradually and they are loosing their original colour and shades. On one hand the size and drawing of figure can certainly be correct and original but on the other one cannot say about the exact tone of their original colours from these photographs. Third method is video recording of some rock paintings of Pachmarhi area. It is so because day-by-day natural weathering and vandalism are damaging these paintings. Thus this is the best process to record the painting with there natural surroundings. All forms and compositions of Pachmarhi Hills have been copied in different methods. During the survey the figures and scenes have been counted at each shelter starting from left to right and from top to bottom. As many of the paintings are damaged and faded by natural agencies and vadalised by ignorant tourist, it is essential to have a factual record of them for the posterity.

(a) Human forms, (b) Animal forms, (c) Scenes, (d) Material culture, (e) Mythology, (f) Nature, (g) Inscriptions

Forms and scenes are studied according to their colour, style, size, technique, period and shelter. Description and analysis of subject matter is the main theme of the thesis. Next is the colour pigments and technology employed in the creation of paintings and finally, chronology, comparative study, motivation behind the art; the aesthetic aspects forms and styles are discussed. The present study is based on data collected from Pachmarhi hills over a period of five years during the suitable weather conditions. Consequently, the sole endeavour throughout the research work by the author has been to carry out an analytical study of the paintings, paying due attention to the above discussed aspects.

The artists painted at considerable heights, standing on ladders or branches of the nearby trees, which existed then near the shelters. Painted walls have been used several times by the painters of later periods, without removing the older paintings. These overlapped or superimposed paintings of different colours; styles and periods may be seen in the many shelters of Pachmarhi.

TECHNIQUES OF PAINTING

Four techniques have been used in the creation of Indian rock paintings. These are wet transparent colour (water colour painting), wet opaque colour (Oil or tempera), crayon (dry colour painting) and stencil (Spray colour painting). The transparent and opaque colour techniques are more common in rock paintings than the stencil technique, which is generally restricted to the execution of negative handprints (Mathpal 1984: 185). The only example of a stencil drawing is mentioned by Gordon from Kabra Pahar in Raigarh area of Madhaya Pradesh (Gordon 1959: 12). The techniques of paintings are not so complicated. Every artist should have either used wet colour or dry colours paste but drawings by means other than colour are also recorded on rock surfaces. These include engraving, carvings and brushings. Except for the stencil techniques, other techniques have been commonly used in the execution of paintings at Pachmarhi. In addition to the paintings, rock engravings are also found in Pachmarhi. The shelters at Rajat Prapat shelter bears a very few designs of symbols filled with white colour, and Astachal shelter also has an engraved horse rider. Only the earlier period paintings are found executed in wet transparent colour technique. Colours are greatly diluted in water; only red and white were applied as transparent. Later period paintings are executed in what is now known as non-transparent, opaque and crayon techniques. Only two inscriptions engraved on the rock surface have been found at Pachmarhi.

The style is different from the technique. The word 'technique' represents the early evolutionary stage of the paintings where as the word 'style' denotes the experimental conditions. It represents the comprehensive and mature stage of the compromise. The conflicting claims in painting of symbolism and representation are very much like the conflicting claims in life of body and soul. And just as the finest forms of life are neither the extreme of hedonism on the one hand nor of asceticism on the other. Both symbolism and representation are easy enough to be described in words. It is a phenomenon that can be readily grasped by the mind (Newton 1945 : 22).

The main qualities of rock paintings which have attracted scholars and artists are the representation of figures including styles, pose and posture, composition, action, movement and different size of forms. Scholars like Breuil (Breuil? 1952 : 32-42) Burkitt (1923 : 187), Kuhn (1958 : 55, 58), Pericot (1961 :201 ? 2), Gordon (1958 : 99 ? 108), Pandey (19975 : 34), Wakankar and Brooks (1976 : 96 ? 103) and Mathpal (1984 : 171) have noticed continuous development in styles of execution. Leroi Gourhan has interpreted all the animal and human forms and abstract symbols on a well determined scheme of four styles on the assumption that in the absence of stratigraphic evidence, style alone can be the base of dating. But again he says, if we attempted this then any formless drawing, of any epoch, would be presumably Aurignacian (1968 : 44).

The style is the basic criterion to establish the chronology and decide the series, but the style alone cannot decide the chronology. We have noticed at Pachmarhi several ways of executing figures of a single period and even in a single composition. In every following composition each new figure varies from the others. Thus if all details of outline, colour filling, decoration and unpainted inner spaces on animal bodies were to be taken into account, the number of styles to emerge would be virtually limitless and therefore of no analytical value. The other factors also contribute in the classification for this purpose; the help of super-imposition and other aspects are necessary.

NATURALISTIC

Generally there were several types of drawings. Though we find both human and animal forms in this first style. But the realism or naturalism has been observed only in animal drawings. The technique adopted is potraying the animals in a freehand wash, no outline was drawn but the figure was completed with wash only. But in many cases, first the outline was completed and than the body was filled, either by a wash of light red or white or by different geometrical patterns. In some cases drawing was completed by a thin white wash and then the details of outlines and strips were finished with brighter white line. In this case the wash outline is so perfect that it gives a naturalistic look of the animal.

REPRESENTATIONAL

The human forms associate with the representational style are simple and without any skill. The figures are either in outline or in silhouette having the formation of square. The torso of the outline figures is decorated with straight, zigzag or horizontal lines. They have been adorned with peculiar headdresses. The figures are shown equipped with stick like objects. The overall picture gives the impression of a hunting society (plate148-). The considerable change in the human forms is also witnessed. There are divergent views regarding the origin of human forms. According to Gordon the human depiction begins with square shape which was followed by stick shape. He further elaborates that where ever square forms are found associated with stick forms, they represent transition. Henceforth, we get major development in huma drawing in stick shape and square shape. According to Wakankar the conception of human drawing beings with the portrayal of stick shape man and square shape style followed it.

In many places square shape figures are found associated with stick shape figures which on their part are equipped with bows and arrows. “At Pachmarhi the figures of both the series are shown together. The earliest human figures drawn in the picture are in square shape. The largest number of these paintings have been depicted in Pachmarhi area and at other places. However, their number is very limited. The square shape human figures have been located so far at Sighanpur, Kabra Pahad, Pachmarhi, Sagar, Khawai, Bhopal and Mandideep areas. These figures are either armed with wooden sticks or bare handed” (Panday S. K., 1975 : 93). Arrows are always fixed with microliths. These figures represent male hunters. However, at Pachmarhi some such figures do represent female form too. In the perspective drawings some time children are also shown associated with the group.

There are numerous variations among square forms. Sometime squares are filled with curvilinear liners. The hands are shown raised up, legs stretched and the head is triangular in shape. Sometime torso is decorated with linear or intricate patterns, while the limbs are shown only in stick forms. The figures are shown generally bare handed, though sticks, bows and arrows are occasionally represented. These paintings are executed in monochrome (dark red or burnt sienna) and bichrome (red and white or creamish yellow). These paintings are shown with breasts, which clearly indicate their feminity. This style has been termed as representational, the naturalism continued in case of animal figures and representational style was adopted for human figures. The earlier animal figures follow the simple decoration but gradually the complicated designs in the form of intricate patterns dominate the paintings. Gradually, this style indicates advancement in the cultural complex of the painters. His perception was gradually developing and he was leading towards the consciousness of his surroundings. Since his experiences were transferred into visual art, he started portraying the narrative groupings.

We get several modifications in stick like forms. The change can be detected in case of head dresses. Torso, though continued, but double or triple lined, as well as the triangular forms of torso also started. Another two more new elements were added to this style. The artists replaced the head with the animal masks. The purpose of the masks was to camoflauge the hunter during the course of hunting and identifying oneself with the totemic deity during the ceremonial dances. The second element has been found in case of animal figures in the form of X-ray drawings. The artist was well versed with the anatomy of the animals. Gradually, he started giving the anatomical details of the animals. He successfully depicted the naturalism in the animal drawings. Instead of depicting the individual animals, the paintings of heards were attempted. Artist has also attempted narrative groupings by depicting family groups engaged in different activities. Not only that even he painted the picture of man-eater tiger in different stages.

SYMBOLIC

A radical change is also marked in the paintings. The convertionalised forms gradually replaced the stick shape human figures. The decoration in case of animal figures was also changed. Afterwards, we get the domination of geometrical forms. We observed many human forms in triangular and rectangular shapes, engaged in different activities. Dancing, fighting and running, horse riders are also found executed in symbolic style. Artists have depicted them in various techniques, and monochrome and bichrome colours. The different religious symbols such as moon, sun, cross, swastika and tree worship are also depicted in the same style. This style is the most impressive manifestation of the intellectual level and represents the great majority of prehistoric art sites of painted or engrave geometric or symbolic figures.

The chronology of the rock paintings is based on the subject matter or cultural content, superimpositions, styles and archaeological findings from the painted rock shelters. The chronological study of Indian rock paintings begins with the work of Col D H Gordon, who devoted much of his time to the study, but only 217 figures from the large shelters of Pachmarhi Hills. He classified them in four series. The first of the series was compared with those of Singhanpur and Kabra Pahar. The second one was confined to Mahadeo hills. The third was mainly from the area around Pachmarhi and could be compared with the Ellora group. He compared the paintings of Jhalai with those of Ajanta. This, of course, was put in a time bracket of about 6th century A.D. The fourth series was compared with the early medieval sculpture, dating between 9th and 13th century A.D. Each series has an early and late phase. He examined this sequence with reference to drawing in 13 more shelters in and around Pachmarhi. According to him a geometric human figure (with rectangular bodies filled in wavy lines and triangular heads) (Series IA) and stick shaped figures (IB) are older than crude figures of hunters (2A and B). Series 3A comprises both geometric figures and crude silhouettes. Series 3A has the most natural animals silhouettes. In the paintings of series 4A and 4B, horse riders and fighters are grouped. In earlier writings he has also mentioned animals of the fifth series executed in greenish yellow. But unfortunately, Gordon's chronology does not clarify his various series. He also did not give a summarized chart with details of features of each of his series.

R K Verma has classified the rock paintings of the Mirzapur area according to style, into four main series, with three subdivisions of Series-II. He has considered the silhouetted drawings of animals as the oldest. The animal figures in Series IIA are either outlined or have partially filled in limbs, while in series IIB natural silhouettes of animal and horse riders are grouped. The scene of elephant trapping at Lithuania-II is assigned to Series IIB. Drawings of Series-IIC comprise crude, outlined figures of hunters. Symbolic and geometric signs characterise paintings of Series III. In the paintings of Series IV crude figures of animals are included. Jagdish Gupta has also classified the rock paintings in 1967 on published material. S K Pandey has classified the rock paintings of Betwa region in 1969. Wakankar, who has discovered the largest number of rock paintings in India, has prepared several chronologies of Indian rock art between 1973 and 1976. Wakankar has classified the entire rock art of India into five periods and 20 styles:

Summary of paintings styles, according to Wakankar in 1976:

| SUMMARY OF PAINTING STYLES | ||

| Style | Features silhouette, Tuskless elephants, Bison and no human figures | Colours |

| I Mesolithic and Earlier [8000(?)-2500 BC] | ||

| 1 | Large silhouette, Tuskless elephants, Bison and no human figures | Faded Red, Brown & Black |

| 2 | Buffalos and Bisons in outline | Red |

| 3 | Animal drawing in thick outlines with partially filled and decorated bodies, Hunters shown, chasing game like rhinoceros, bisons, antelope and elephant. | Red |

| 4 | Bisons, deer and antilope in outline and non-geometric body decoration. | Red |

| 5 | Animals with body decoration in several geometric patterns and partially filled limbs. Main animals are rhinoceros, tiger, ox, deer and antelope. | Red & Bichrome |

| 6 | Geometric and floral designs hut shaped symbols and animals. Figures of Style-3 and human figures of Style 4 and 5. | Red & Purple |

| II Neolithic\Chalcolithic and Iron Age (2500 ? 300 BC) | ||

| 7 | Silhouette drawing of bison, buffalow, elephant, ox, black buck, monkey, and lizard. | Red & Brown |

| 8 | Simple and stylized outline of cattle, boar, jackal, deer and antelope-overlapped by drawing of Period-III. | Red |

| 9 | Figures depicted, crude and thick white drawing of animals and triangular bodied human figures. | White |

| 10 | Silhouettes drawings of animals ox, tigers and human. | White, Yellowish White |

| III Early Historic (300 BC - 800 A.D.) | ||

| 11 | Symbols like Swastika, hollow cross design and inscriptions. | Red, White, Green & Yellow |

| 12 | Animals with outlined, partially filled and large decorated bodies, Hunter with large bows and arrows, resemblance with Nevasal. Navadatoli pottery designs. | Red & Purple |

| 13 | Drawings of horse and elephant riders Swordsman and archers in outline and wash. | Red & White |

| 14 | Polychrome decorative patterns, Gupta and Shankh Inscription. | Red |

| 15 | Multi coloured decorative designs. | White, Red & Yellow |

| 16 | Social and Cultural life in natural silhouettes and scene of tribal conflicts. | White & Red |

| IV Medieval (800-1300AD) | ||

| 17 | Stylized drawing of cavaliers and soldiers. | Red, White & Orange |

| 18 | Silhouettes and linear drawings of elephants, horses and human forms. | Red & White |

| V Recent (1300 Present) | ||

| 19 | Swordsmen and camel like animal in outline. | Crayon Charcoal |

| 20 | Geometric human figures in double Outline along with Devanagri scripts. | Red |

However, the efforts of Wakankar (1978), Gordon (1958), Verma (1964), SK Pandey (1969) and Mathpal (1984), who have been able to put forward minimum workable criteria and guidelines for choronological interpretations, are well perceived.

There are only three periods reflected in the rock paintings of Pachmarhi. One - scenes of a society of hunters and food gatherers, which can be called Prehistoric period (Mesolithic). Two - scenes of using chariots, huts, agriculture, pottery and domestic animals, which can be termed Protohistoric period (Neo/Chalcolithic). Three - scenes of fighters, riders and the use of metallic weapons, which undoubtedly, belong to the historic period.

(a) Prehistoric period - Mesolithic, Late Mesolithic.

(b) Protohistoric period ? Neolithic/Chalcolithic, Late Chalcolithic.

(c) Historic period - Historic, Late Historic.

Pachmarhi is a small township on a plateau located in the folds of the Satpura ranges in Central India. It is 210 kms from Bhopal and 52 kms from Pipariya. Pipariya is the nearest railway station on the Bombay-Howrah mainline via Jabalpur. The hills of Pachmarhi have a complex of rock shelters, very difficult to count. More than 55 shelters have been surveyed here and there still be many more to discover. The reason as to why most of India's rock art is in Central India is geological. The Satpura and Vindhayan ranges consist of soft sand stone, which over millions of years, has weathered into hills containing overhanging rocks and cliffs and caves of many shapes and sizes. From early prehistoric times till a few centuries ago these provided shelters for humankind. The archaeological excavations particularly at Jambu Dweap in the past have proved that the early Stone Age man occupied these shelters. Numerous microliths have been found at the shelters in the Bari Aam area. Most interesting findings for me was a pendant made of the tooth of an herbivorous animal probably a monkey, and yellow ochre coloured nodules at the shelter in Bori area.

The location of Pachmarhi from the ecological point of view is such that it meets the basic needs of human beings to survive - food, (in the form of animals and vegetables) water and shelters. The aboriginals exploited the edible flowers, fruits, tubers, honey and animals available for food. The natural sources of water are numerous and perennial too. The hills have the shelters, large enough to accommodate 200 to 300 people and provide protection against wind, sun and rain. It is therefore obvious that prehistoric man occupied these shelters for nearly 10,000 years! Many of these shelters contain large numbers of paintings in varying states of preservation. They are placed at varying angles on the rock faces, often overlapping other paintings and varying sizes, from a few centimeters to several meters.

Indian rock paintings, mainly concentrated in Central India, have only recently received the attention they deserve. The majority of these paintings are in Madhaya Pradesh. Pachmarhi and the surrounding Mahadeo hills make a rich center of the paintings. It is interesting to note that the rock surface was not prepared in any way before painting, and often uneven surfaces and corners were chosen for painting, while broad and even surfaces, where you may expect existence of paintings, are left unpainted. The painted shelters are often located at considerable heights and access to them is very difficult. There are many shelters which cannot be used for dwelling but are painted rather better than those more suitable for dwelling purposes. Some of the shelters have numerous figures, painted with several superimpositions of figures, whilst some shelters contain a very few figures. The majority of the paintings are red and white, showing up admirably on the rock surface. A few paintings are also in yellow colour. Infact, paintings are executed in fourteen different shades, of these three main colours - Red, White and Yellow. These colours are obtained by grinding pieces of rock found locally and mixing the powder with water or some other binder. Nodules of hematite (geru) were used for red, and limestone or Caroline for white. It is believed that fluffed out sticks were used as brushes and porcupine quills for doing the fine work. Some cupmarks and cupules have been found in the Astachal and Ghurmar shelters.

The styles of paintings range from naturalistic to very symbolic or abstract. Three main styles of execution are recorded. The oldest drawings are more naturalistic or realistic and elegant and the later ones are more representational. Drawings are outlined, monochromic, bichrome and without light and shades. Nearly all drawings of animals are shown in profile and in motion. Outlines of animal forms are generally realistic and the bodies are decorated with geometric patterns.

Horns and legs are drawn in a slight three-quarters posture. There are a few figures in an x-ray style, showing the fetus within the womb. Inner details of the body are usually omitted. In rare cases, human figures, eyes, nostrils, ear, mouth and other facial details are shown. No figures are shown with shadows on the ground. There is neither background with human and animal figures nor perspective and foreshortening. Animals in herds are drawn in horizontal rows, which are one above the other. The paintings of the Pachmarhi area may be classified broadly in three groups. Firstly, depicting scenes of hunters and food gatherers, secondly pottery makers and cultivators, and thirdly fighters and horse riders with metallic weapons. First is considered prehistoric while the second protohistoric and the last historic period. The most common subjects of prehistoric paintings are animals - bison, boar, elephant, sambhar, gaur & antilopes. Besides, there are rabbit, fish, lizard, scorpion and small creatures. The drawings of animals are very naturalistically executed and show the animals in various postures and moods - standing, walking, running, leaping, looking back etc. Hunting scenes are also very common. Usually, the hunters are shown in small groups. They were shown with sticks, bows and arrows, stone tipped spears and traps. They face large animals like bison. Human figures are shown with different activities such as ritual dancing. A very interesting painting of ritualistic dancing 8 meters long can be found at Mount Rosa shelter, which is the most beautiful drawing of the mesolithic period in this area. At the same shelter, in one instance, a woman is extracting milk from both breasts. It may be a representation of the mother Goddess. Mesolithic people were decorating their bodies with ornaments. They wore necklaces, bracelets, bangles, pendants, elbow bands, knee bands and anklets. Men wore long loose hair and women braids. They used sticks, slings, spears, bows and arrows, traps for hunting. Their arrows and spears were barbed with microliths. These people used many kinds of masks, headdress and animal hides. The masks were different in shape and were used for hunting and dancing. Headdresses were crowned with feathers, antlers and horns.

Drawings of the protohistoric period show a gradual development like pottery making, building of hutments and means of transport (cart, chariot), agricultural implements, and other man-made utensils are depicted. The execution of figures is more representational. Drawings of the historic period show a society of fighters and riders, soldiers armed with swords and shields. It is very clear but these paintings do not depict the life of the cave dwellers. In other cases this period encompasses varied subjects such as honey collection, fishing, and domestic chores. Musical scenes are depicted with different instruments - harp, drum, pipe and cymbal. In one instance a very unique and interesting depiction of Head Hunters has been seen. This kind of depiction is only found at Pachmarhi in India. These figures are holding severed human heads. The figures and severed heads are highly decorated with ornaments like earrings, necklaces, crowns, topknots, and wearing loincloths. All the figures have sharp features and are proportionately made. The figures are holding severed heads in the right hand and sword in left hand. Another interesting painting of the Bori area shows a very clear face with both eyes face in front posture. It is a very unusual depiction, which is found only in this area. The subject matter of Pachmarhi area also includes a large number of different symbols and signs, mythical creatures, trees, bushes, decorative designs and inscriptions. There are also the scenes of collecting honey with the help of pets and music too. In another painting the fishing activity is shown with the small conical net, which is called Kumna by the present tribal of Pachmarhi.

The descendants of the original hunters and gatherers and artists of this region are the Korku and Gond tribes who still uphold some of the traditions of their ancestors. In the rock paintings, their ancestors are depicted dancing in pairs or in a row and playing musical instruments. They hunted animals and collected honey from hives of wild bees. Their mode of dress was quite simple. The women used to carry food and water and looked after the children. The forebears of the present day tribal people had a variety of ways to express the magic of their beliefs, rituals and taboos. The tribes living in these hills make memorials made of wood. Carved teakwood boards placed under a sacred Mango tree honor the dead. The subject of the carvings are totally unrelated to the life of the deceased but the style and subject - horse rider, sun, moon, tree and hut - is similar to the late period paintings depicted by their predecessors in the past on the mural of the rock shelter. They also decorate the walls of their wattle hut and this activity seems to have its roots in the cave dwelling traditions of their ancestors. Man and horses of geometric construction are randomly spaced across the walls; such paintings are done during the rainy season or on festive occasions bearing close resemblance to those found in the painted shelters.

The paintings found in Pachmarhi Hills are faded or partially obliterated and in fragmented condition. Some of them are covered with the thin layer of calcium or moss. The colours of some of the paintings have merged with those of the rock. The degree of natural preservation of these paintings varyies according to the location of the shelter, exposure to sunlight, rain, wind and worst of all, the unaware or mischievous human beings! Most of the shelters have now become accessible due to the development of tracks and roads, a consequence of the development of tourism in this area and the religious significance attached to the place. The paintings now face threat of human vandalism, and local tribal groups are now going deeper to explore the forests for their livelihood. For example, the rock paintings at Nagdwari are being badly damaged during annual festivals of Maha-Shivaratri and Nagapanchami, when pilgrims visit the shrines in thousands. The pilgrims are also damaging Neemgiri, Chitrashala and Agenda shelters that are located on the same hills of Nagdwari.