Getting to the Kimberley was quite a logistical challenge. With the collapse of Australia's major regional airline the year before, and the subsequent contraction of tourist services to the Kimberley, finding our way to the Mitchell Plateau was not as simple as could be hoped.

The easy bit was getting from the eastern seaboard to Darwin. Dave and Rachel met us in Darwin on the 1st of July after travelling from their home in Dunedin on the south island of New Zealand the day before. The evening was spent rechecking our gear and taking advantage of our last opportunity for beer and steak at the local pub.

The next morning we were back at Darwin airport, boarding a turbo-prop flight to Kununurra in Western Australia. Because of quarantine regulations, we could not bring any fruit, vegetables or nuts across the border from the Northern Territory. We had allowed ourselves a couple of hours in Kununurra to buy most of our food. For an hour we madly rushed around the small Kununurra supermarket grabbing staples like biscuits, flour and rice. Before the trip commenced we had meticulously planned for each meal and came armed with a list of must-get items. After the shop, we spread our gear out on the veranda of the local Tourist information centre. The pile of food was large but we managed to divide it between the four of us, leaving some to put in the food cache. We planned to leave the food cache at the starting point of our walk, return to it after doing a 10 day loop, then use the food in the food cache to sustain us on our walk back to civilisation.

While sitting on the information centre veranda, surrounded by food and equipment, the pale cast to Dave's face was troubling. He related a tale of his workmates in Dunedin having come down with the flu as he and Rachel were leaving the country. By the time we reached Kununurra, Dave was starting to feel the symptoms. However, after coming so far he decided to press on and see how things panned out.

After lunch, bags stuffed, we headed back out to Kununurra airport to meet the Cessna that we had chartered for the next leg to the Mitchell Plateau airstrip. At the airport we and our bags were weighed. We were told that 6 kg had to go before we could take off. Either we would all have to run around the airport a few hundred times and loose some weight or leave behind some our food. We chose the later and left some of our luxury items such as self-saucing puddings, custard, and onions.

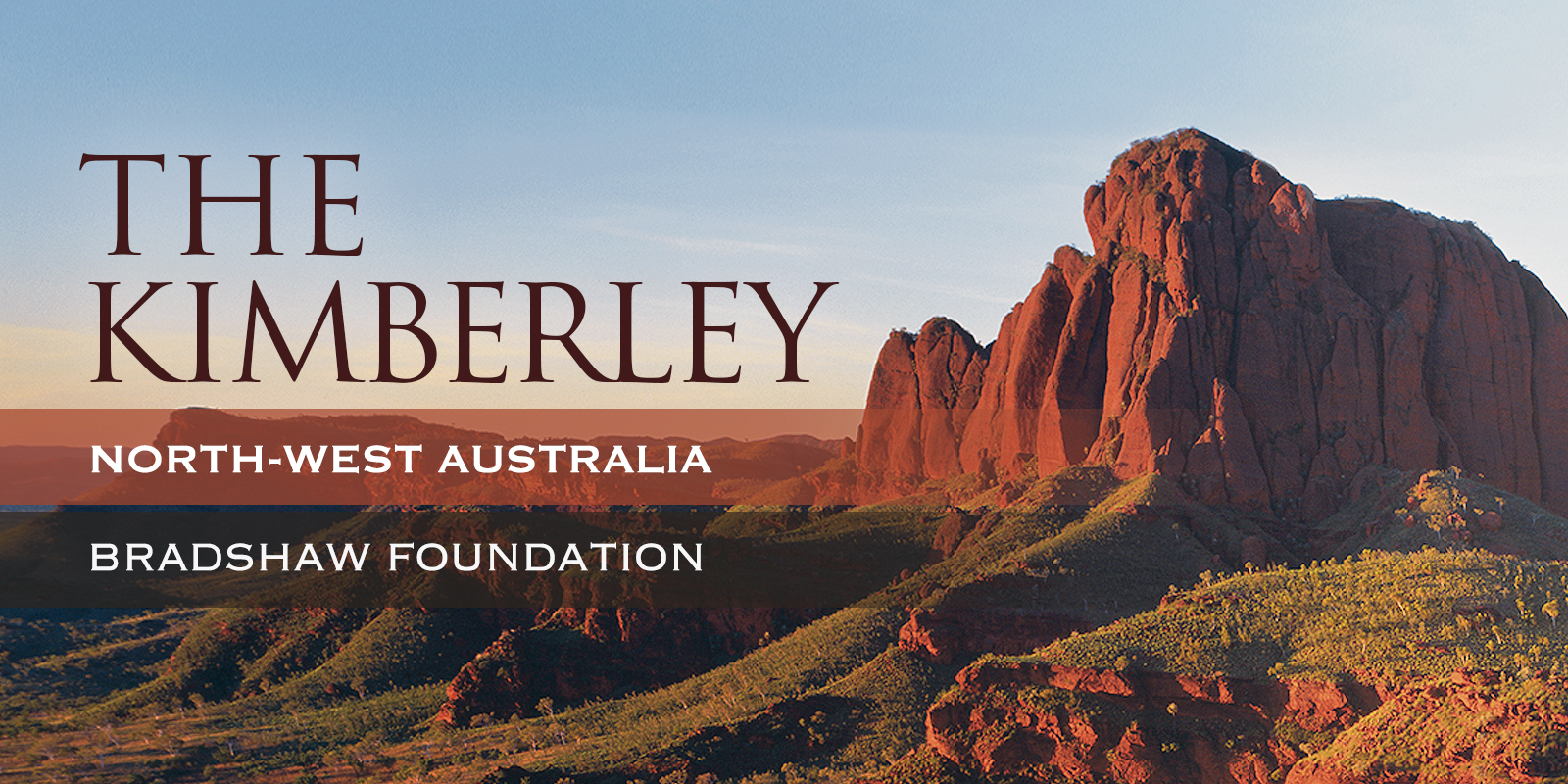

We flew out over the green patchwork of the Ord River irrigation scheme at about 2.30pm, and on to the Mitchell Plateau! Apart from the spectacular arid-land scenery, dissected by meandering rivers reduced to chains of pools by the dry, the two-hour trip was reasonably uneventful. We were soon flying over the red Mitchell Plateau, scattered with distinctive Mitchell Plateau palms. We touched down at the Mitchell Plateau airstrip in the afternoon heat and were met by the helicopter that would take us the remainder of the distance to the starting point of our walk.

As we would be returning on foot to the Mitchell Falls campsite in a few weeks time, we were all keenly taking note of the lie of the land and water availability as we flew off towards the south west. It looked promising and there were quite a few pools of water visible in streams with quite limited catchments. We noted the curious paths and trails at intervals beneath us and were told by the pilot that quite a few feral cattle roamed the grassy plateau country. The chopper set us down a half hour later on the sandy bank of a creek overlooking a pristine waterfall. Our cameras came out as the helicopter and its associated safety and link to civilisation thudded off into the deepening shadows of evening. We were alone at last, and quite excited by the prospect!

With only a half-hour before sunset, we set about securing our food cache in a nearby tree. Having heard about the Northern Spotted Quolls, which were very curious and would eat anything, we enclosed the food in two industrial plastic bags and then in a sturdy canvas bag, before hanging it as high as we could manage in a tree.

From our drop point we would walk out in a big 10 day loop, arriving back at the waterfall to replenish supplies, and then continue on back to Mitchell Falls and the Mitchell Plateau airstrip. The mood around the campfire that night at the top of the waterfall was very animated, with high spirits and much anticipation of the days ahead.

We arose bright and early the next morning and set off down to the stream below the falls. The plunge pool at the base of the falls was idyllic! It was deep and dark and lined with pandanus, and contained pristine and clear water and unspoilt nature at its finest! We lingered for a while before continuing down the rocky stream bed. Long deep pools occurred at intervals, separated by rocky sections comprising broken boulders, testament to the power of the wet season flows.

As the day began to warm up it became clear that Dave was suffering from a bout of the flu. The first day of walking saw us cover only 2.5km from the chopper drop, with frequent rest stops. That night, while camping in a pretty little grassed clearing by the creek, it was decided that Dave and Rachel would remain in the general area and meet us back at the food drop in 10 days. This was a big disappointment for them, but better than pushing on and risking aggravating the ailment. Emma and I would push on as planned, with the party's GPS and EPIRB.

The next ten days were a fantastic mix of deeply dissected plateaux and spectacular gorges. The rugged Kimberley scenery was breathtaking and wild in the extreme. The walking was often hard, as crevices in the sandstone were often filled with vine forest or spinifex, and we carried heavy packs. Green ants were an ever-present pest and just about every tree or bush harboured a nest of these easily agitated insects.

Finding water in this country was never a problem, even in June, as most of the streams still flowed, if only at a trickle. We planned to move away from water only to cross between streams, a distance of no more than 15 km. This was usually done in the early morning, when it was relatively cool. Sometimes, however, the walls of the gorge containing the stream we were following became sheer, and we were forced to climb up onto the plateau to avoid swimming with the less desirable reptilian inhabitants of the area. We were always weary of estuarine crocodiles, and only swam in cascades or small pools where we could be assured that we were alone. They can be found even in the fresh water reaches above the tidal influence. Fortunately, we saw few salties. Their freshwater cousins were quite abundant, however. At night after turning in we would often see one or several sets of pink reflective eyes in the beams of our torches.

Finding campsites was generally not a problem. Our priority when choosing a site was that it be near a source of water - camping away from water was not really an option because of the heat. Water also provided a plentiful source of fish to supplement our supplies, and sometimes also freshwater prawns. Along the rivers, suitable sand-banks and rock platforms cropped up frequently. Since the prospect of rain is pretty much zero this time of year, we didn't bring a tent and slept under the stars. We did bring some protection from biting insects; a mosquito net held up with tent poles, which we affectionately called the "Mega Mozzie Dome".

Apart from the trickle of water and ever-present frogs, night-time was generally very quiet. We felt a little saddened that this land, which for tens of thousands of years was alive with the voices and activity of people is now silent. This feeling was especially strong when quietly contemplating each of the many decorated caves and rocky overhangs we encountered. Much of the art we found was faded and obviously quite old. We came across representative panels of both the Bradshaw and Wandjina styles. Often Wandjinas were painted right over the top of the older Bradshaw style. Some Wandjinas were still in a fine state of preservation and we spent hours at guessing how long it might have been since people lived and painted in this area. It might have been as late as the 1940's!

Our food budget consisted of staples such as flour, rice, and dehydrated potato. We relied on catching fish for protein - a gamble that paid off handsomely as the local fish had never encountered a fisherman before (well not since the original inhabitants fished these waters). In some pools, fishing was hardly a challenge, with a willing punter climbing on the line no matter what adorned the hook. A variety of herbs and spices, and some dehydrated vegetables flavoured our meals. Snacks included cordial crystals for a sweet drink, and a limited supply of carob bars.

The weather was predicably fine and sunny. Daytime temperatures typically reached the high twenties. This made the walking a bit sweaty, especially considering that our food-loaded packs weighed over 20kg early on, but generally quite pleasant. In contrast, the nights were a lot cooler than we expected, sometimes uncomfortably so. Some internet-based research preceding the trip suggested that we might expect night-time minimum temperatures of 10-12 degrees. Consequently, our sleeping kit consisted of a couple of light Polarfleece blankets, a couple of inflatable mattresses and some thermal clothing. As it transpired, the whole top end of Australia experienced below average temperatures while we were there, with night-time temperatures on the Mitchell Plateau of down to 2 degrees C. After some chilly nights, we discovered that rock platforms could be relied on to radiate heat well into the night, and so provided excellent refuges from the cold.

On the tenth day, we returned to the food cache where we were to meet Dave and Rachel. We were eager for some company and conversation. It turned out we would have neither. As we approached the site where the chopper had dropped us off and where the food cache had been hung, it became apparent that Dave and Rachel were nowhere to be seen and there were no fresh footprints. Our anxiety was soon dispelled when we spied a thermal top wrapped around the food cache bag. Dave and Rachel had been there!

A note within the bag told a curious tale. A couple of days after we left them Dave's condition had still not improved. So, when presented the opportunity to return to Mitchell Falls by a passing helicopter (surely a rare occurrence in this remote area) they jumped at it. They flew back to Mitchell Falls Campsite in the chopper, and its wash erased evidence of their passing!

Disheartened at the loss of their company, but glad that Dave and Rachel would not have to walk the last distance to the falls while sick, we spent the rest of the day at the food cache washing clothes, recouping strength and eating our fill.

The next day we set off across the plateau towards Mitchell Falls, leaving the gorge country behind. The walking on the plateau proper was much easier than it had been in the gorge country. The terrain was flat and generally grassy. We quickly worked out what size of catchment was required for a stream to still contain water in billabongs from our 1:100k maps and wound our way across the countryside following these lifelines. We did several detours onto hills to look for rock art, but evening always found us back at a billabong or stream, sometimes accompanied by curious brolgas or red-tailed black cockatoos. Even the smaller streams tended to have flat banks with many grassy camping options near water.

After nearly a week of easy walking we could tell we were nearing Mitchell Falls by the near-constant drone of helicopters ferrying tourists from the campsite to the falls. They would start at sun-up and continue until dusk. In a strange way they were a welcome sight as they contained people, which we had not come across for weeks.

Our first contact was with a retired couple who had been dropped at the falls by chopper. They had had been cruising in luxury on a cruiseboat that had come from Darwin and was heading to Broome. They had come for a morning swim, choppered in from their cruise boat, which was moored in Prince Frederick Harbour. They would be returning to the boat for a BBQ on the beach that evening. Surprisingly, they envied our freedom to walk as they had been cooped up on the boat for a week. We would have been quite happy to have a few days relaxing on their boat!

Soon afterwards we were at the falls and our trip almost over. We spent a couple of hours sitting overlooking the falls and taking photographs before starting the hour and a half walk to the campsite. It felt strange to be on a well-trodden track after weeks of picking our way through the bush. Again we were keen to catch up with Dave and Rachel and exchange stories.

The campsite was full of travellers in 4WD vehicles of every make, and with every luxury. We couldn't see Dave and Rachel, so went to the chopper pilots and asked them. We'd missed their departure for home by two days! Disappointed, we wandered over to claim a camp spot for the night. We felt very much the odd one out with only our packs to claim a spot, rather than a 2 tonne vehicle. It was easy to see why Dave and Rachel had left. The campsite was unpleasantly hot and shadeless by day, and filled with dust from passing 4WD's. At night the bare earth was uncomfortably cool.

In the morning we were up with the sun again and walked over to chat with the chopper pilots before being flow the last 15km to the airstrip. Our Cessna was waiting to take us back to Kununurra when we arrived. The day was bright and sunny, as had been all the others, and we were sad to leave. Now, sitting here writing this account of our trip, we can not wait to return, the Kimberley has a strange allure and most who go there just want to keep going back.....

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ Australia Rock Art Index

→ Introduction to the Australia Rock Art Archive

→ Rock Art of the Kimberley

→ Rock Art Australia (RAA)

→ Dating the Rock Art of the Kimberley

→ Australia's Oldest Known Rock Art

→ Film - Griffith University's Laureate

→ ABC Radio National 'Nightlife'

→

Experts rush to map fire-hit rock art

→ The aftermath of fire damage to important rock art at the Baloon Cave tourist destination, Carnarvon Gorge, Queensland, Australia

→ Studying the Source of Dust

→ Rock Art of Western Arnhem Land

→ Australia's Aboriginal People

→ The Kimberley

→ Out in the Back Country - Hugh Brown

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network