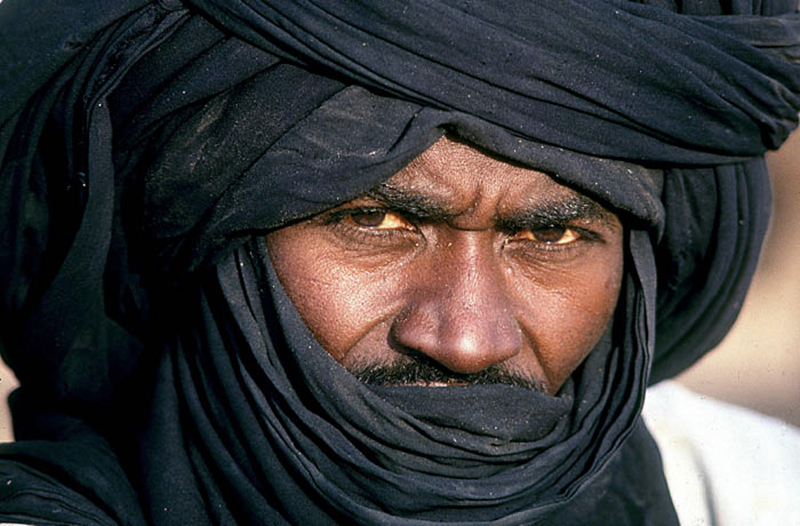

Tuareg caravaneer. The head veil, known as 'taguelmoust', may exceed ten metres in length

Salt may well have been humankind's earliest addiction. Salt drove economies, opened trade routes and settlements, even sparked bitter wars. Today we take it for granted - something to flavour our fries. But in Africa's sahel, salt remains a valuable commodity - indispensable for animals and men. In Niger, Tuareg caravans continue across the Tenere Desert to fetch salt from the Bilma oasis and barter millet for dates. Five milleniums since the story of Lot's wife was first told, salt is still made in pillars and transported by camels to distant markets. This site celebrates the survival of one of the world's most ancient and fascinating cultures - The Caravans of Salt.

Each winter Tuareg caravans cross Niger's Tenere desert to fetch salt from the Bilma oasis and barter millet for dates. Salt is indispensable for Sahelian livestock and scarce local deposits combined with heavy consumption ensure profitable markets. In the past, for protection, caravans assembled and travelled en masse. They were accompanied by a representative of the Agadez Sultanate, who negotiated safe passage and determined salt prices. Frequently over 20,000 camels took part. This system has long disentegrated and nowadays, participants consist of families and friends who club together under the guidance of a 'madagu' - chief or headman.

The famous minaret of Agadez mosque. Once an important cross-roads on ancient trade routes, Agadez is still occasionally visited by caravans for refurbishments

Caravans are on their way by autumn. Since the Tenere is completely barren, camel fodder is cut beforehand and compressed into compact bales. Only certain varieties of grass are suitable, principally 'grifis' and in the Air massif 'amassa'. Following droughts, the absence of this grass will prevent caravans from departing.

Each camel bears two fodder bales and two goatskins of produce for bartering in Bilma - millet, beans, maize, cheese and dried vegetables. To take advantage of grazing, the inintial pace is leisurely. On reaching the Tenere's dunes, however, caravans march from morning till night. These dunes are longitudinal in type, running in great parallel ridges from north-east to south-west. The grain of the land roughly corresponds to the caravans bearing. This partly explains the salt trade's success over centuries, and greatly facilitates navigation, particularily since the Bilma and Fachi escarpments cut across the trail. Here in this awesome wilderness the madagu's experience proves invaluable. Locating appropriate dune troughs through which to travel is important, for some are dead ends, others contain soft and loose sand. Nightly halts are a tremendous relief after covering some fifty kilometres per day. Camels are hastily unloaded and fodder bales arranged into windbreaks. Tea is immediately brewed followed by a hot supper of boiled millet flavoured with a herbal sauce.

The isolated Fachi oasis provides a welcome respite. Nestling beneath an escarpment and encircled by palm groves, the approach to Fachi is extraordinarily beautiful. The more northerly Tuareg - Kel Air - by pass Fachi, taking a direct route via Achegour well. Every few weeks a lorry ploughs beween Bilma and Fachi, transport from Agadez is rare. The oasis is therefore more dependant on caravans than Bilma, but Fachi's salt is deemed second grade and most caravans press on to Bilma - another four days.

Situated on the Kaouar's escarpments southernmost edge, Bilma is the regional administrative centre. The inhabitants, like Fachi, are Kanouri. The salt pits of Kalala - the salt producing district - date back at least a millenium, and are still vitally imortant. In fact, Bilma's salt output has actually increased, though the bulk is now transported by trucks. A heavy brine is found here by digging pits six to eight metres deep. These oblong pits are arranged in groups with a low stone wall marking each holding's boundary. The rains of summer 2006 inundated and temporarily destroyed many pits.

Clockwise (top left) A rope is tossed over the neck of an obstinate camel to couch the animal for loading; There is always a 'madagu' or caravan chief - the most experienced and respected participant; Camel fodder is cut before the barren Tenere. Only a particular grass known as 'grifis' and 'amassa' are suitable; Caravans constantly need rope for attaching camels together and securing loads; A life giving glass of tea or 'chai'. Within the harsh and frugal world of caravans, the delicate preparation of tea seems strangely out of place. Small enamel tea pots and glasses are handled with great care and cleaned immaculately; Preparing tea and supper - usually a boiled porridge of millet with a herbal sauce. The man to the left is weaving rope lengths from palm shoots; Crossing a grassy plain. The caravaneer is playing the 'kuge' - a small metal percussion instrument, much associated with Kel Gress caravans; Old friends and acquaintances meet in early autumn to form caravans.

Salt extraction is basically a simple though tedious procedure. High summer temperatures and evaporation cause a salty crust to crystalize over the brine surface. The crust is continuously broken down,causing fragments to sink and compose a sediment. The sediment's upper layer yields the purest salt, known respectively as 'egil' or 'beza' by the Tuareg and Hausa, and destined for human consumption. The pillars are called 'takiss' or kantou' and weigh 21 kilos. Small cake shaped moulds - 'fochi' weigh 2 kilos, and are of the same mix as pillars. Both these forms are from impure salt and for livestock. Kanouri women visit the caravan camps to barter and gossip. Bartering ratios remain fairly constant at three volumes of dates for two of millet. Only drought and conflict drastically alters this balance. Trucks also enter Kalala to load the smaller and less fragile 'fochi' mould. There has been a tendency by journalists, and some ethnologists, to romantacize and portray caravans as " doomed by the combustion engine". This is misleading. True, the Tuareg no longer hold a monopoly on salt distribution and transport, and caravan numbers are falling, but their economy has survived remarkably well, and profit margins on salt sales compared to millet prices broadly in line with thirty years ago - even taking into account the CFA devaluation in 1994.

Clockwise (top left) The 'taguelmoust' may be slackened or removed when working or in the company of friends; Facing east, against bitingly cold winds, a caravaneer prays to Allah.

Trucks obtain salt by off loading supplies of various goods - macaroni, oil, flour, through a complex system involving the village headmen or 'chef du quartiers', who in turn pass the goods to the salt workers on a pro rata basis - hard cash is seldom used. The Kanouri much prefer dealing with caravaneers, and two forms of 'fochi' are now made - a slightly larger version and of superior quality is reserved for the Tuareg.

Buyers in the salt markets of southern Niger and Nigeria are well aware of this. Whenever I ask a Tuareg what he thinks about trucks, the answer invariably is "Bilma has a lot of salt." Bonds of mutual help and benefit between Tuareg and Kanouri go back a long way. Often I have seen Kanouri women passing up a chance to trade, waiting patiently instead for their usual caravneer to arrive.

In the photographs above a caravan crossing the Tenere's dunes towards the oases of Fachi & Bilma. Each camel bears two fodder bales and two goatskins of millet for bartering against dates. A goat - for bartering against salt - is perched on a camel. The 'madagu's experience here is invaluable - he will guide the caravan safetly through the dunes. Sheep and goats are often carried across the Tenere atop camels. Both Fachi & Bilma lack fresh meat. If a cash sale is not possible, they are bartered for salt & goods.

Fachi provides a welcome respite, and most caravans spend a day here before pressing on to Bilma - another four days. Fachi's salt is deemed inferior to that of Bilma. Bilma. Salt deposits crystalize on the surface - the water table is only a few feet deep. A 'marabout' or holyman of Fachi. Fachi has many marabouts, who make a living by offering prayers for the safety of caravans. The Tuareg, as tradition demands, must obtain their blessing before departure, for which they pay a token amount - either cash or goods. Kanouri woman of Fachi barters dates for millet. Strong bonds of mutual help and benefit have long existed between both parties. Bartering ratios are affected by famine or conflict, but generally, two volumes of millet are exchanged for three of dates.

Clockwise (top left) Following the piste towards the solitary Mount Amzeqeur; The ritual of 'Ragu'.Young novices, referred to as 'ragu' - sheep, are subjected to a mock attack on their first crossing of the Tenere; Dusk over the beautiful and isolated Fachi oasis; Caravans camped outside Fachi oasis; Tuareg; Sheep and goats are often carried across the Tenere atop camels; Caravan crossing the Tenere's dunes towards the oases of Fachi and Bilma.

With camel fodder at a premium, business is concluded with a week. Most camels manage six pillars, six salt cakes, plus two goatskins - now filled with dates instead of millet. Recrossing the Tenere, weakened animals suffer terribly. The bleached skeletons of those that perish litter the trail.

Clockwise (top left) Bilma. Salt deposits crystalize on the surface (above), Kalala' - Bilma's salt pits. By digging pits six to eight metres deep (below); A 'marabout' or holyman of Fachi; Kanouri woman of Fachi barters dates for millet; Kanouri making a salt pillar. The mould is made from a hollowed-out palm tree trunk; Caravan recrossing the Tenere westwards into the setting sun; Women visit caravan camps gathering camel dung for their fires; Gathering in 'beza' from the brine pan's surface.

After resting briefly at home, the Tuareg continue south into southern Niger and Nigeria. The tempo now eases and the caravan south is more relaxed. Frequently older men or children - who may not have been strong enough for the Tenere - take part. Salt and dates are now sold in favour of millet. Millet provides the caravaneer's family with a staple diet, and surplus stock is bartered in Bilma the following season.

Most villages in the Damergou region of southern Niger come to life once a week with a market. Here, the Tuareg display their salt and dates. Herders - Hausa and Fulani - haggle humorously over prices. The Hausa ,in particular have a sweet tooth for dates. The Tuareg are obviously reluctant to sell below a certain price, but remain keenly aware that salt must be turned into hard cash to buy millet - and millet prices rise sharply following the harvest.

Clockwise (top left) Salt pillars are carefully examined before purchase; Salt pillars or 'kantus' stacked ready for buyers; Darker moulds the 'kantou' and 'fochi' - for livestock use; Kanouri women fill containers with water near Kalala; The strongest camels carry some 300 kilos plus a rider; Women making 'fochi' salt cakes; Kanouri woman with salt cakes - 'fochi'; Watering camels after the Tenere. On leaving Bilma; Firewood, cut and brought across the Tenere, runs low.

In Feb. 2006 pillars fetched 3500 CFA in Damergou markets. Prices were broadly similar in 2007 - 2008 though many Tuareg reported that they could obtain 3500 CFA only within the Maradi region with Damergou falling to 3000 CFA. Salt prices rise towards summer - when livestock need it most, but most Tuareg - except the Kel Gress - cannot afford to wait. As with the Kanouri of Bilma, caravaneers usually deal with the same farmer each year. He will look after their interests, take care of any problems and hold their millet until they return home. While caravaneers go about their business, exhausted camels finally rest and graze.

Clockwise (top left) Each morning Bilma's inhabitants visit Kalala to barter and chat; The bulk of Bilma's salt is now transported by trucks; A 'marabout' - holyman prays for the safety of a caravan; A 'madagu' leads camels across the dunes; Caravaneers rest with their families; Heading south.

With the naira's devaluation and increasing bureaucracy, the salt caravans of the Tuareg tend not to enter Nigeria so much. Once salt is sold and millet purchased, the Tuareg may seek out transport or haulage jobs - conveying goods from village to village.

Clockwise (top left) Water is kept cool and fresh in goatskins - 'abiok'; Father and son readjust a camel's load; Going south, caravan tempo eases; Prized camels are adorned with amulets; A youngster tries in vain to repair an old radio; Children rush to meet their fathers; In Damergou, the Tuareg go to market selling salt; Garare market. Buyers haggle over salt prices.

In the past, the transport of ground nuts was a routine occupation for the Tuareg, but today, it is no longer profitable. Now is the time to buy presents for wives and families, as well as footwear and clothes. Then, towards the late spring, just before summer the rains fall, the caravan returns home.

Clockwise (top left) Villages in the Damergou region of southern Niger each have a weekly market; Tuareg with veil; The Tuareg arrive at first light to display their salt and dates; Tuareg; A farmer's wife offers food to their Tuareg guests; Camels make way for Fulani and cattle; A Hausa youth stops the Tuareg to buy some dates.

Clockwise (top left) The farmer will look after any problems and provide up to date advice on the markets; A Hausa millet farmer passes by to chat; The Agadez based charity - HED Tamat has established a depot in Tessaoua; Buying millet from a Hausa family near the border with Nigeria; Caravaneer examines a pair of sandals in the market; Even when caravans don't enter Nigeria, Tuareg still visit Kano.

Franco Paolinelli

The Bradshaw Foundation would like to thank Franco Paolinelli for his text and photographs used to publish this section of the Bradshaw Foundation website.

Clockwise (top left) Shoots from the Doum palm - 'tagait' are often bought and resold profitably; The huge market of Talata Mafara near Sokoto, northern Nigeria; Similar straw mats - 'shereben' as for protecting salt pillars are now used for millet sacks; Goatskin sacks - 'amital' are now refilled with millet; Talata Mafara - close of market. With constant devaluation of the naira.