George Nash, Genevieve von Petzinger, Aitor Ruiz Redondo, Juan F Ruiz Lopez and Yamandu Hibert.

In January 2022, the UAE Origins Project team undertook an extensive fieldwork programme along the cliff sections and hinterlands of Qarn bint Sa’ud (also known as Biba bint Sa’ud), a small limestone escarpment that forms part of the northern limit of the Al-Hagar Mountains. The project was set up to identify and record prehistoric sites and rock art that date from the Palaeolithic to the proto-historic periods. The focus was to explore the caves, rock shelters, overhangs and relic land surfaces that are located in the inlets that naturally cut into this isolated landmark north of the city of Al-Ain and searched for evidence of early symbolic behaviour and settlement patterns. The UAE Origins Project team explored additional areas along the Jebel Hafeet and the limestone escarpments along the Omani border further towards the east of Al Ain. It is within this part of the Arabian Peninsula where significant prehistoric rock art is found.

The Qarn bint Sa’ud stands north of the city of Al Ain (centred upon 24°23'6.35"N, 55°43'6.68"E) [Map]. The limestone outcrop is orientated NW-SE and measures 520m on its NW-SE axis by 245m E-W. The summit rises above an arid sand desert area that was wetter and lush than at present. Exposed around the outcrop among a dominant dune system is a series of relic land surfaces that have revealed extensive flint scatters that date possibly from the Middle Palaeolithic to later prehistory.

The caves, rock overhangs and rock shelters that contain evidence of prehistoric archaeology are located within three naturally formed semi-circular enclaves [Fig 1]. Each enclave contains evidence of Bronze/Iron Age burial-ritual activity, in the form of denuded stone cairns [Figs 2 & 3]. Up to 23 burial cairns stand close to the eastern lower slopes of the rock outcrop and date between the 2nd and 4th millennium BCE. Locally, these monuments are referred to as Hafit-type tombs.

Seven of least 23 burial cairns that occupy the western hinterlands of Qarn bint Sa’ud

Seven of least 23 burial cairns that occupy the western hinterlands of Qarn bint Sa’ud

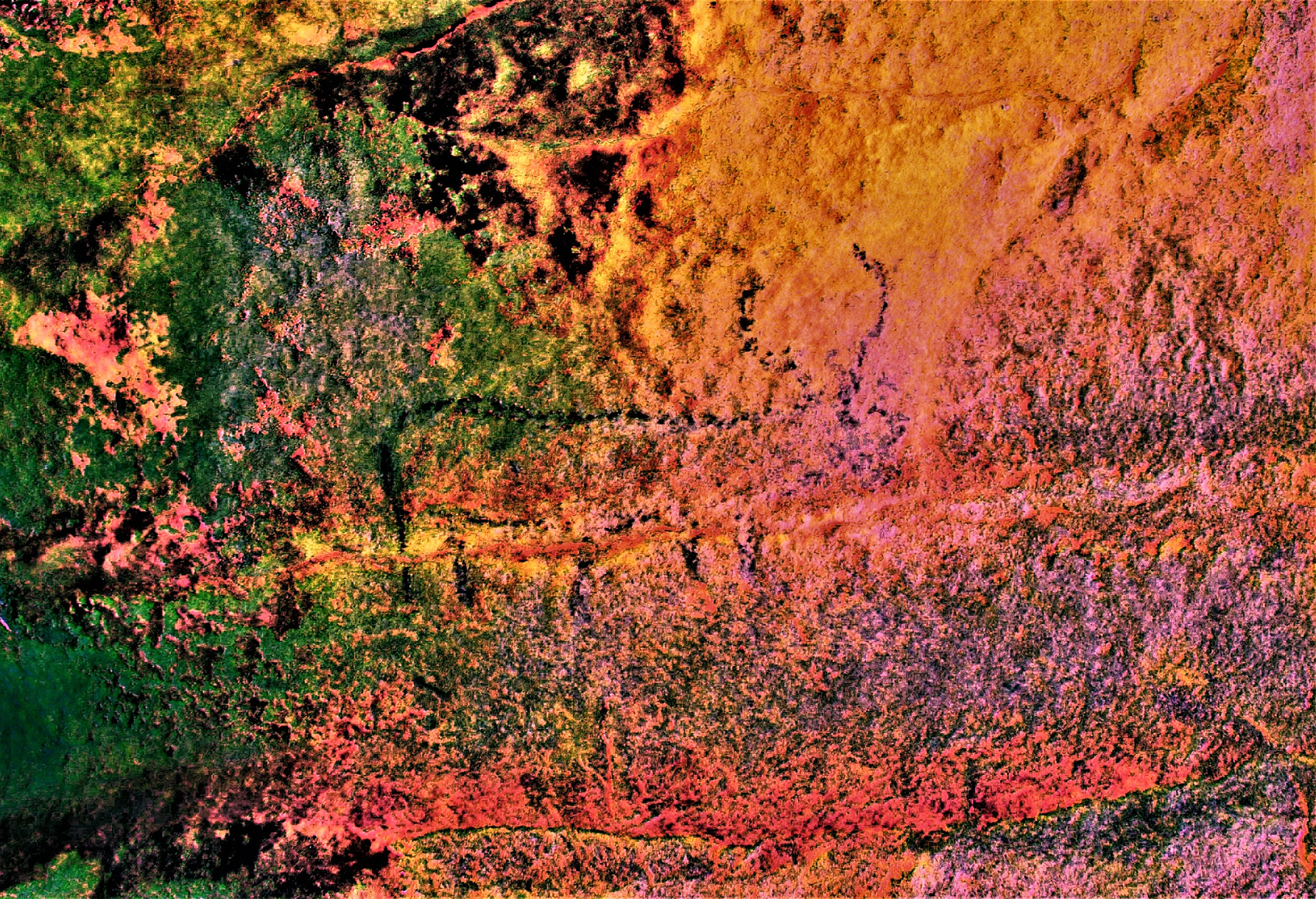

Exposed on a vertical panel, using the desk-based algorithm D-Stretch are at least three phases of imagery that include bovines, cervids and historic wassim marks

The cliff-face and rock shelter within the central enclave on the western flank of Qarn bint Sa’ud and views across the arid landscapes

The UAE Origins Project team explored the majority of the accessible rock shelters within the eastern flank of the rock outcrop where prehistoric rock art can be found; 18 or more engraved and painted panels in total. The rock art assemblage is substantial and varied, and probably represents at least four phases of artistic endeavour, possibly extending over 7000 years of prehistoric and historic activity [Fig 4]. On the summit of the outcrop are several Iron Age stone monuments that have been reconstructed. Due to time constraints, the western flank remained unexplored.

Inspection by the team revealed that each enclave contains identical drift geomorphology, comprising a windblown dune system that extended some distance up-slope, towards three exposed limestone cliffs on the eastern flank [Figs 5 & 6]. These windblown deposits cover mainly scree (shattered stone fragments and boulders of varying sizes) that originate from the cliffs above. This scree deposit overlaid a laminated limestone bedrock. Within the hinterlands where the Bronze Age cairns are located were exposed relic land surfaces that yielded prehistoric flint and chert.

Lithics recovered from the eastern flank of the site (A-28). All stone artefacts show great diversity in raw materials using non-local flint and chert variants. The two larger pieces – 16 and 17 are of possible Palaeolithic age

During the myriad human migration period and expansion events, our ancestors have settled and moved across this part of the Arabian Peninsula for many thousands of years, around the various wadis where resources were abundant. Based on paleoenvironmental evidence, the region would have been wetter and the climate less arid during the specific intervals throughout the Quaternary. Regionally, during this time there would have been a radically different landscape which was affected by dynamic sea-level and climatic change; both would have had profound effects on the environment and the flora and fauna. Within this area of the Arabian Peninsula is evidence of early human activity, as witnessed through various flint scatters and stratified sites found further to the north in the Emirate of Sharjah. In and around the eastern slopes of Qarn bint Sa’ud later prehistoric flint was recovered from relic land surfaces that stand close to many of the Bronze Age cairns.

A section of a stone vessel of unknown date found close to the eastern flank of Qarn bint Sa’ud

A standard methodology was used to analyse the flint and stone artefacts that included description and photography [Figs 7 & 8]. The assemblage comprised cores, flakes, chips, bladelets and a small number of retouched tools. The lack of typical Neolithic arrowheads and associated production waste was notable. The bladelet assemblages included small (less than 10mm in width) and symmetric elongated blanks, which were struck from bladelet cores. The microlithic character of the lithic assemblage, coupled with the great variety of raw materials used may be held indicative of a highly mobile human population. Retouched tools included a variety of ad-hoc implements such as notches, retouched blanks and small end scrapers. The morphology and typological variability of the artefacts, coupled with their relatively fresh character, meaning that they did not undergo considerable alteration by environmental factors, suggests a possible mid to late Holocene age (later prehistoric). However, two flakes made on non-flint materials and advanced stages of weathering suggest that they may be considerably older and possibly Palaeolithic in date.

It has been known for some time that prehistoric engraved and painted rock art is present within several caves of the east-facing cliffs of Qarn bint Sa’ud; however, this intriguing imagery has been poorly recorded; partly due to the limited technology available to archaeologists at that time and the inaccessibility of some of the panels. To make sense of this unique assemblage, a preliminary photographic record was made in each cave, overhang and rock shelter, as well on those panels identified on the vertical cliff sections that occupy the eastern part of the Qarn bint Sa’ud. It should be noted that no prehistoric rock art or associated archaeology was present on the western side of the escarpment. Using a variety of photographic techniques, including high-resolution digital photography and de-correlation stretch (D-Stretch), the team identified potential hidden pigmentation and patinaed engravings that had hitherto remained undiscovered from previous expeditions.

D-Stretch is a digital desk-based enhancement tool that was developed by Jon Harman in 1995 and was originally developed as a remote sensing GIS tool by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The software comprises a multispectral image enhancement tool, exclusively based on the RGB matrix of the digital pictures, that has been specifically redeveloped to maximise colour manipulation of, say, rock art images, in particular, paintings and has been widely used by rock art specialists. An optimum enhancement is usually achieved when photographing paintings that contain various shades and hues of red, yellow and black pigmentation. Fortunately, most of the painted rock art from Qarn bint Sa’ud were made from locally sourced iron oxides. D-Stretch can usually help to distinguish between natural inorganic secretion and applied pigments produced by human agency.

In 1957, a Danish team discovered prehistoric rock art in and around the caves and rock shelters of the central enclave on the eastern flank of Qarn bint Sa’ud. These sites and the smooth sections of the vertical rock face had yielded a variety of painted and engraved images which are considered to be similar in style and subject matter to rock art found in the central region of the Al-Hagar Mountains in neighbouring Oman.

A plethora of engraved images were found on sections of the central enclave cliff-face

Original and D-Stretch images of a building with prehistoric and Islamic elements

To the northwest of the entrance of the cave are several painted panels that stand c.1 m above a laminated limestone floor. One of these panels includes a single shoeprint [or sandal], probably originating from the Islamic phase and painted on a weathered limestone surface [Fig 14]. The shoeprint is considered an important motif in Islamic culture and religion.

Several metres SE of the entrance of the cave is another complex panel that includes the painted outline of several superimposed cervids and bovines that are painted over a large bull figure. The back and neck of the painted bovine appear to acknowledge the upper edge of the rock panel. A historic tribal wassim mark completed the panel narrative. The presence of bovines appears to represent an early rock art phase for this site and clearly indicates that when painted, the environment was very different to what we witness today.

Located within the northern section of the enclave is a small cave that is accessed via a narrow ledge. Much of the rock art within the cave has previously been recorded, albeit using now outdated and potentially damaging techniques. Unlike other rock panels within the immediate area of Qarn bint Sa’ud, the rock art is hidden on the walls and ceiling of the cave. The engraved and painted iconography comprises wild animals such as antelope and bovines that would have once roamed the immediate landscape, some 4,000 to 8,000 years ago.

The most visible rock art is organised into two panels, one occupying the ceiling, and the other, on a wall panel that lies close to the entrance. Both panels were recorded using photogrammetric techniques (Fig 15, Fig 16 and Fig 17).

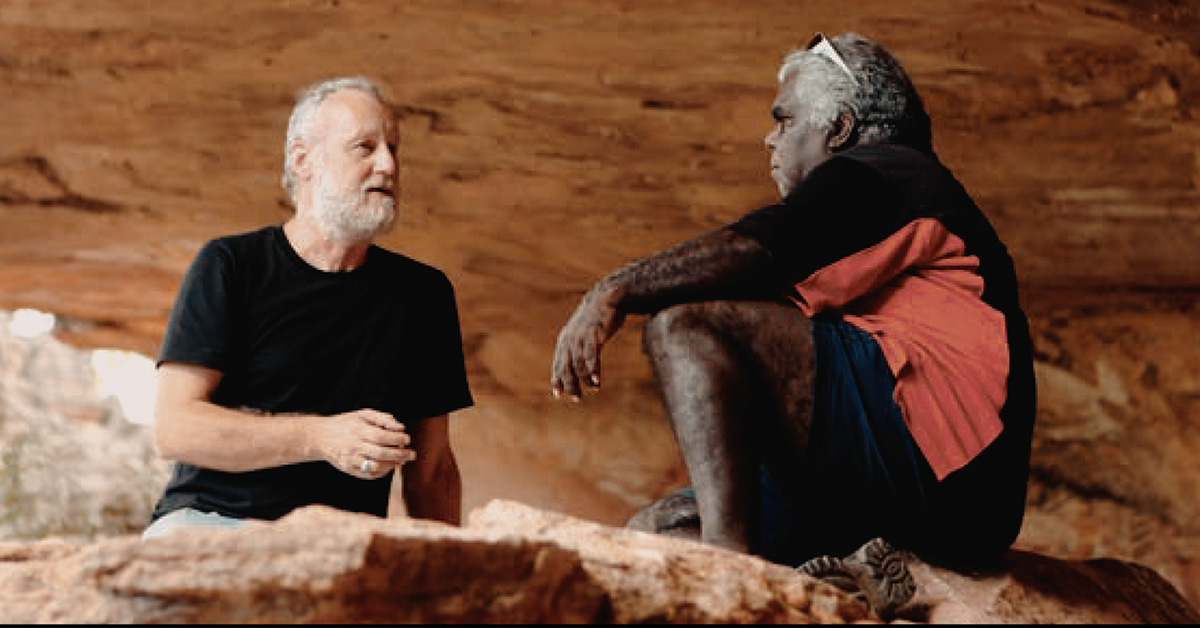

Colleagues Dr Aitor Ruiz-Redondo and Dr Juan F. Ruiz López recording rock art in one of the caves along the eastern flank

Original image showing an engraved bovine with later tooling marks covering the lower section of the body

D-Stretched image showing an engraved bovine with later tooling marks covering the lower section of the body

Pecked outline of a probably engraved antelope (Oryx) with an internal mesh design

Within the NE section of the cave, near the entrance is an engraved antelope, possibly an Oryx and a bovine [Figs 21 & 22]. The antelope has been infilled with a simple mesh motif, while the bovine is constructed as a simple outline. In addition to these two figures is a possible horse, although a further visit to the cave is required in order to verify this. Additional motifs have been discovered in the inner ceiling and walls of the cave and remain unrecorded.

Pecked outline of a bovine. This animal indicates the presence of a grassland environment

The lithic and pottery assemblages, the funerary monuments and the rock art constitute a unique and significant archaeological resource. The site has been the focus of archaeological interest since the late 1950s. Over the relatively recent past [during the latter part of the Holocene], much of the eastern (and western) hinterland has been inundated by dune deposition. The dune formations probably overlie ancient relic land surfaces which contain spreads of lithic material that date between the Bronze Age and the Palaeolithic. This spread of lithic material indicates the significance of the Qarn bint Sa’ud site and at least 20-30,000 years of human activity.

In terms of rock art, the site has yielded many phases of prehistoric and historic activity. The caves, rock shelters and overhangs have yielded a variety of painted and engraved rock art that can be roughly associated with the large rock art assemblages from the central area of the Al-Hagar Mountains in neighbouring Oman.

The engraved images that include the pecked snake are the most complex of all rock art present within the Qarn bint Sa’ud site. Each panel appears to show a plethora of imagery, some of which is superimposed, suggesting periodic engraving events over a long period. We would stress though that the imagery from this site possesses its unique idiosyncratic form and style.

The limestone escarpment is the only visible topographic feature within the area and would have been an important focal point, meeting place and encampment for prehistoric communities. It is more than likely that early prehistoric nomadic and semi-nomadic communities used this natural focal point and others to guide them through what was a rather featureless landscape. In later prehistory, communities become sedentary and Qarn bint Sa’ud would have been used as a funerary site during the Bronze Age, suggesting a degree of permanency.

In general, the different features observed on the bulk of the flint stone tools found at the site are characteristic of a complex palimpsest, meaning that they are the result of repeated and discreet human activities taking place recurrently over a long period of time. The homogenous techno-typological patterns of stone tool manufacturing techniques and raw material diversity, however, may be indicative that these have been made by populations sharing a specific transmitted cultural knowledge. The possible Palaeolithic artefacts found at the slopes of the escarpment further attest to the recurrent visits to this landmark amidst the encroaching dune systems through the latter part of the Quaternary. The presence of rock art, as yet difficult to date reveals that prehistoric communities were settled and were probably the first communities who can lay a sedentary claim on this intriguing landscape.

Extracts of this article were published in Current World Archaeology 2022.

Bretzke, K., 2020. The Palaeolithic record from the Central Region of the Emirate of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, in: Bretzke, K., Crassard, R., Hilbert, Y.H. (Eds.), Stone Tools of Prehistoric Arabia, Supplement to Volume 50 of the Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp. 15–26.

Eisenburg-Degen, D., Nash, G.H. & Schmidt, J. 2016. Inscribing history: The complex geographies of Bedouin tribal markings in the Negev Desert, Southern Israel. In L. Brady & P.S.C. Taçon (eds.) Relating to Rock Art in the Contemporary World: navigating symbolism, meaning and significance. University of Colorado Press.

Fossati, A., 2019. Messages from the Past: Rock art of the Al-Hajar Mountains. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Groucutt, H.S. & Petraglia, M.D., 2012. The Prehistory of the Arabian Peninsula: Deserts, Dispersals, and Demography. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 21(3): 113-125.

Harman, J., 2008 [2005]. Using Decorrelation Stretch to Enhance Rock Art Images. http://dstretch.com/AlgorithmDescription.html

Hilbert, Y.H., 2014. Khashabian A Late Paleolithic industry from Dhofar, Southern Oman, BAR International Series 2601. Archeopress, Oxford.

Hilbert, Y.H., Usik, V.I., Galletti, C.S., Morley, M.W., Parton, A., Clark-Balzan, L., Schwenninger, J.-L., Linnenlucke, L.P., Roberts, R.G., Jacobs, Z., Rose, J.I., 2015. Archaeological evidence for indigenous human occupation of Southern Arabia at the Pleistocene/Holocene transition: The case of al-Hatab in Dhofar, Southern Oman. .Paléorient. 41: 31–49.

Nash, G. H., Fox, Y., von Petzinger, D., von Petzinger, G., Ruiz Redonder, A., Ruiz Lopez, J.F. & Hibert, Y.H., 2022. Unlocking a hidden landscape: Preliminary fieldwork at Qarn bint Sa’ud, Abu Dhabi. .Current World Archaeology. Vol. 116, 32-38.

Nayeen, M.A., 2000. The Rock Art of Arabia. Hyderabad: Hyderabad Publishers.

Tikriti, W. Y. A., 2011. Rock art in Abu Dhabi Emirate. Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi Culture and Heritage.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation