Brent Sinclair-Thomson and Sam Challis

Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

To cite this article: Brent Sinclair-Thomson & Sam Challis (2020) Runaway slaves, rock art and resistance in the Cape Colony, South Africa, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 55:4, 475-491, DOI: 10.1080/0067270X.2020.1841979

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2020.1841979

The protracted colonisation of southern Africa’s Cape created conditions of extreme prejudice and violence. Slaves, the unwilling migrants to the Cape, comprised a mixed group of individuals from the Dutch and British colonies: people with Malay, Malagasy, East and West African heritages. They combined to form the labour force for the colonial project, along with indigenous Khoe-San trafficked within an illegal domestic unfree labour economy. Escaped or ‘runaway’ slaves joined forces with groups of ‘skelmbasters’ (mixed outlaws), who themselves were descended from San-, Khoe- and Bantu-speaking Africans (hunter- gatherers, herders and farmers). Together, they mounted a stiff resistance that held up the colonial advance for many decades from the late eighteenth century until the mid-nineteenth century. Engaging in guerilla-style warfare, they raided colonial farms for livestock, horses and guns. The ethnogenesis of such raiding bands is increasingly coming to the attention of archaeologists encountering the images they made of themselves in rock shelters, as well as the spiritual beliefs that they held in connection with escape and protection. The ‘reverse’ or ‘entangled gaze’ provided by this painted record gives us the perfect opportunity to view something of the slave and indigenous resistance from outside the texts of the colonial written record.

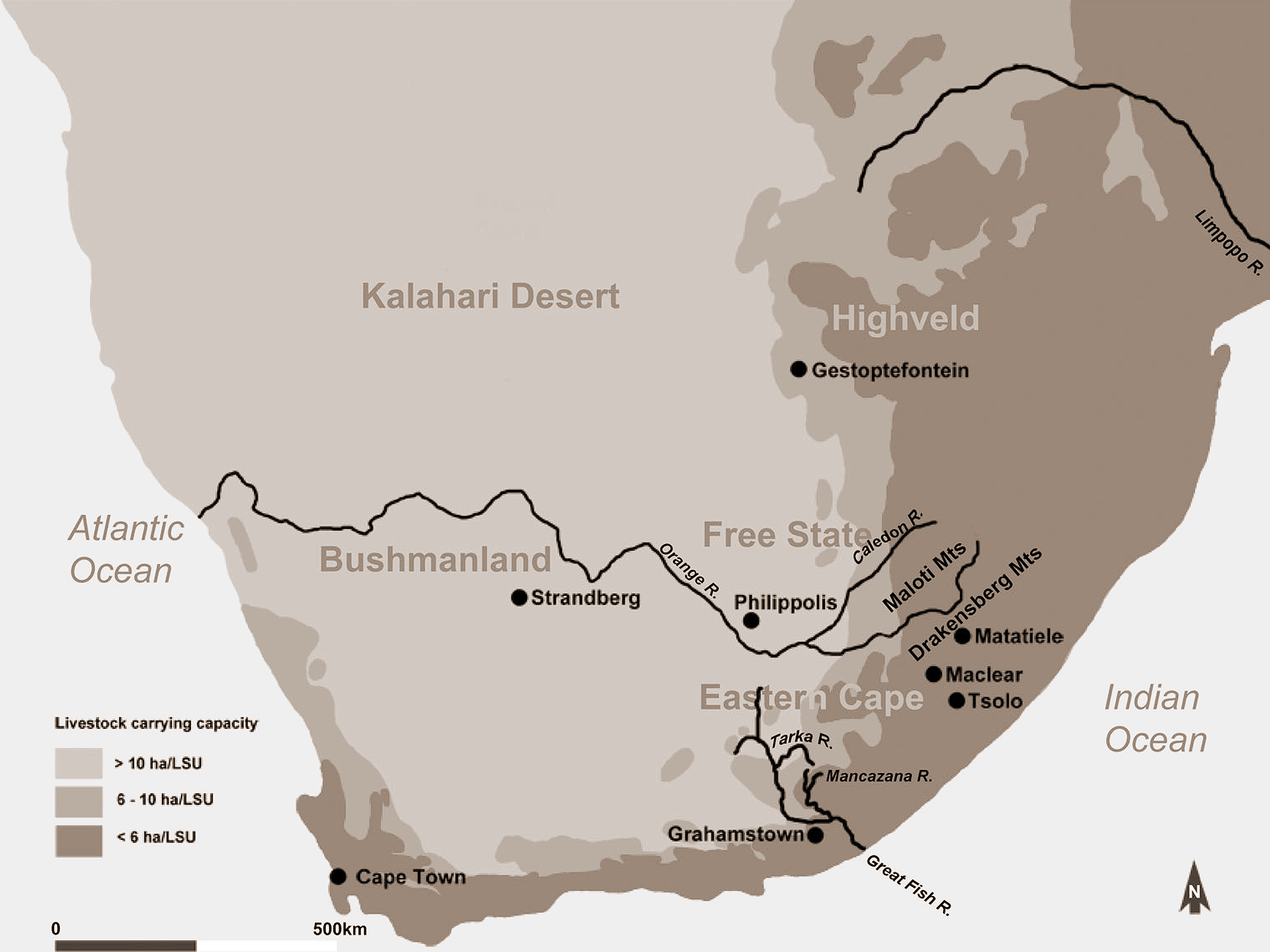

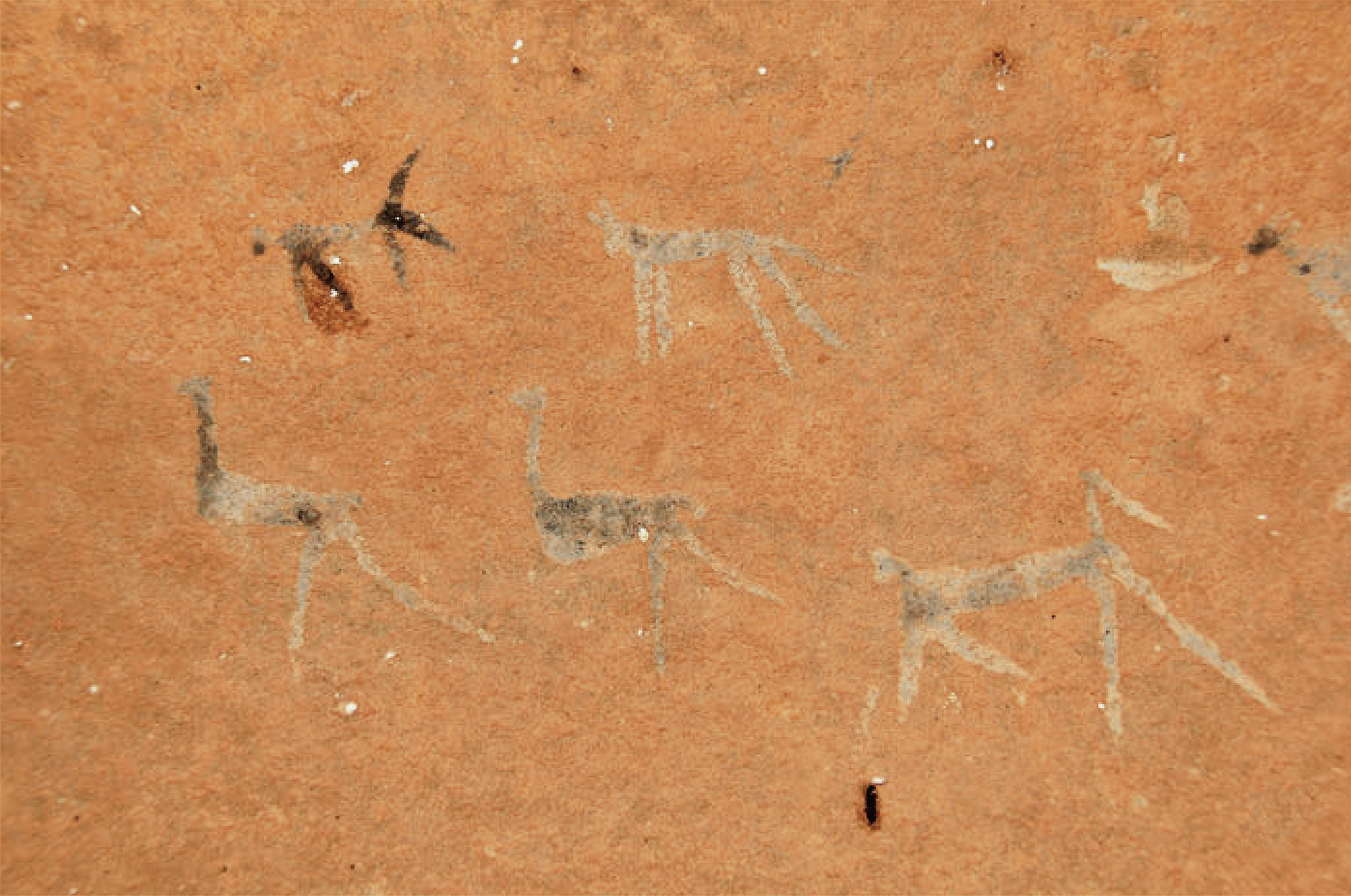

Rock paintings occur in both the Winterberg and Maloti-Drakensberg of South Africa (Figure 1) that date to the colonial era owing to the appearance in them of horses and guns, among other things. As opposed to the world-famous ‘traditional’ images of the hunter-gatherer spiritual experience — shaded to create an almost photographic likeness of antelope, for example — these later images differ in subject matter and technique. They are typically painted in a rougher manner than the refined earlier art and with a reduced colour palette, the hues of which are unshaded and ‘poster-like’ (Loubser and Laurens 1994). In some cases the poster-like images of people with horses and guns seemingly raiding livestock appear alongside rough-brush-painted and finger-painted ver- sions with the same subject matter, something we discuss later with respect to Figures 4 and 5. Given the short time frame in which they could have been painted, it is likely that they were made, if not at the same moment, then in rapid succession to one another, speaking to the historically attested heterogeneous nature of raiding bands in these areas. Importantly, the localities where the paintings occur are often the same as those described by colonial travellers and administrators from the late eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries as the hideouts of groups consisting of ‘Bushmen, Hottentots and runaway slaves’ (Napier 1849: 226). In this study we examine aspects of the practice of slavery, both official and illicit, in South Africa and resistance to this institution, which was often enacted by running away and joining groups of bandits in the mountains adjacent to the colony. These bandit groups mounted further resistance by stealing livestock from European-owned farms that were in many cases their former places of captivity. Drawing on ethnographic accounts, we are able to demonstrate that rock art in these localities appears to be concerned with those slaves’ understandings of escape.

For this contribution we incorporate by necessity the written record because we are conducting archaeological investigations in the colonial era, but we go beyond this by examining the archive of the colonised, particularly those involved in acts of resistance, in the form of rock art. We follow Worden (1982), Penn (1999) and others in attempting to show the plight and perspective of the oppressed: the ‘reverse gaze’ of Ouzman (2003) or ‘entangled gaze’ of McMaster et al. (2018). That is to say, in the almost unrecoverable archaeological signature of runaway slaves one can trace something in the rock art of a direct voice (in the case of the indigenous) and an indirect voice (in the case of immigrant slaves), as well as the mixing of the two. We begin with the historical background — who the slaves were, immigrant and indigenous; in what ways they became embroiled in events; how they appear in the historical record (in the economy, in resistance, in escaping, in jails); and how they appear in southern African society (in indigenous and newly- formed African groups). The second part of our paper then turns to the rock art itself, which is often found in secluded mountain fastnesses or lookout points where indigenes and unwilling migrants were hiding out.

Following Ross’ (1983: 3) emphasis on the slave experience being one of ‘resistance, not acquiescence’, we stress that in southern Africa a search for large-scale slave rebellion is a misrepresentative of slave treatment, where one finds better evidence of the phenomenon of desertion. Desertion in effect is the rebellion for which some historians are looking (cf. Ross 1983: 5). Escape was only the beginning of the lives of those who offered resistance, but where others (e.g. Ross 1983) perhaps focus on the conditions of slavery and flight of slaves,1 we emphasise the alliances forged between immigrant and indigenous slaves alongside free indigenes (cf. Alpers 2003: 59). Runaway slaves or drosters2 comprised an unavoidable component of the colonial borderlands, being historically visible in recorded raids and materially visible (if less easy to read) in their places of refuge, where they made images of these concerns within their own belief systems. As Penn (1999: 4) adroitly remarks:

fugitive gangs very often represented micro-societies in which oppressed people from a variety of backgrounds – slaves, Khoi, ‘Bastaard-Hottentots’3 and Company deserters — grouped together in units of mutual support, sharing a common consciousness of oppression and developing a tenuous form of multi-ethnic solidarity.’

This phenomenon finds expression elsewhere, and later, as the colonial stranglehold on the Maloti-Drakensberg mountains tightened, in the ethnogenesis of creolised bands of raiders who included painting in a system of ritual observances to ensure escape and protection (Challis 2014, 2016, 2018).

Two representations of oppressed individuals in the Cape Colony: (a) Louis van Mauritius, who led a rebellion of 300 slaves in the Cape in 1808, is shown here in the National Heritage Monument sculpture The Long March to Freedom. Reproduced with permission of the artist Barry Jackson and the National Heritage Project Company; (b) ‘Portrait of Júli, a Faithful Hottentot’ by William Burchell (1822: 160).

When we refer to indigenous slaves we use the terms ‘Khoe-San’, who were illegally pressed into unfree labour, and ‘African farmers’ (Xhosa, Zulu, Sotho, Tswana and so forth), whose involvement increased later on in the history of colonial expansion; Morton 1992). Elsewhere, we have explored the effects visible in the subcontinent’s rock art resulting from contact between indigenous hunter-gatherers (San and those ancestral to them), incoming African herders (ancestors of the Khoe) and incoming African farmers (isiNtu language-speakers), as well as contact with colonists and fugitives of European descent (Challis and Sinclair-Thomson in press). Of course, this necessarily entails the entanglement (e.g. Der and Fernandini 2016) of runaway slaves escaping into the hinterland and finding refuge among all the above groups (Alpers 2003; cf. Lightfoot and Martinez 1995). In doing so, we detailed the delicate matter of nomenclature (i.e. ‘San’, ‘Khoe’ and ‘Khoe-San’; see Besten 2011: 188–190) in the writing of southern African history. Suffice to say here that, although linguistically related, the two groups are often self-designated as quite distinct yet, in the archaeological and historical records, they can be difficult to distinguish.

The historical record is muddied by the use of the terms ‘Bushman’ and ‘Hottentot’, which are often equated with ‘San’ and ‘Khoe’ respectively, but their deployment rests unconvincingly on early travellers’ grasp of perceived ethnicity and appearance. Importantly, today the hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari prefer to be known as ‘Bushmen’ (e.g. Barnard 1992), even though this name, like its counterpart ‘Hottentot’, is considered pejorative in the Cape. Unfortunately, terms such as ‘Bastaard-Hottentot’ appear in the archive as a specific colonial category (in this case an exonym that becomes an endonym) that still serve as pointers in our investigations.5

Richard Allen (pers. comm. cited in Alpers 2003: 52) draws attention to the distinction made between fugitives who remained close at hand, perhaps waiting for, or living off, their fellow, still bonded, slaves for a short time period (small or petit), and those who escaped more permanently and at a greater (grand) distance as to be able to live in relatively free Maroon societies. Alpers (2003: 59) sees the integration of runaway slaves into frontier societies as a key feature of the period:

‘sometimes individuals and small groups of slaves sought to escape enslavement altogether by seeking shelter with indigenous people … [constituting] an important intermediary point along the continuum from petit marronage to grand marronage.’

We would add to this that it is central to the formation of many such groups, particularly those labelled ‘Banditti’, or ‘skelmbasters’ (skelm from the Afrikaans ‘trouble-maker’ and baster from ‘bastaard’/mixed; Giliomee 1992: 458), whose identity (at least to the settlers) comprised ‘Bushmen, Hottentots and runaway slaves’ (Napier 1849). These three categories were not, however, necessarily distinct, especially as indigenous populations became illegally enslaved.

With colonial expansion, the indigenous Khoe-San came to occupy a position that was akin to slavery, despite this being officially outlawed. Much controversy has centred on whether these individuals ought to be considered ‘true’ slaves or as another category of unfree labour (see, for example, Newton-King 1999; Penn 2005: 140). For instance, Khoe peoples’ movements were far from free, as exemplified in the Caledon Code of 1809, which required them to carry passes and allowed officials to designate individuals, willing or otherwise, as labourers among the settlers (Crais 1990: 206). Nigel Penn (2005: 111) notes that Khoe were forced into servitude in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as Dutch colonists took both their land and their livestock. Crais (1990: 195) links this development of servitude with the growth in the production of commodities, especially beef farming, on the colony’s borders. Penn (2005: 111) argues that although the Khoe at first received some benefits, namely wages and being allowed to retain stock on their employers’ land, this changed from the late eighteenth century with the development of the commando, or militia, system. These militias, consisting of local European farmers and their servants, who were themselves often of Khoe-San descent, became a powerful tool used by the colonists to enforce increasingly unfair obligations on the Khoe who were fast losing any remaining liberties. Because Khoe-San within the Colony were expected to, and relied upon, work, when unemployed they were considered idle or ‘vagabond’. The expression ‘Vagabond Hottentots’ came into use (Burchell 1822: 258) and those so classified were thrown in jail if they could not account for themselves. As Thomas Pringle (1835: 179) observed in his inspection of the Fort Beaufort jail in 1822:

‘Others were merely Hottentots out of service, who had been apprehended by the field- cornets, and sent here until some white man should apply to have them given out to him on contract.’

He also noted that thrown together in the gaol were Xhosa farmers, other Khoe-San as well as wild Bushmen, by which we know Pringle meant those who had not been brought up on farms (Pringle 1835: 179):

‘There were wild Bushmen, too … The offence for which they were in general confined was absconding from the service of the farmers, after having, under the pressure of famine, sold themselves and their children to thraldom for a mess of pottage.’

The Reverend John Philip (1828 Volume 2: 265–266) noted that Khoe-San children were passed from one family to another (for an illicit fee) so that they might not be traced. Thus, was the hunter-gatherer population enslaved:

‘The greater part of the farmers being without slaves, their sole dependence for servants is upon the Bushmen, and other aborigines of the country’ (Philip 1828 Volume 2: 267).

Although the commandos were said to be a retaliatory measure against stock theft by indigenes, they were more often deployed to capture Khoe-San to be used as indigenous slaves in bonded servitude (e.g. Penn 2013). In many cases the men who were caught by a commando were massacred, while the children would be either kept by the members of the commando or sold into slavery (Penn 2013: 193). It is to this internal slave trade that the Khoekhoe leader Klaas Stuurman was referring when he told John Barrow near Algoa Bay that “We have a great deal of our blood to avenge” (Barrow 1801: 93–94).

There are many first-hand accounts from European travellers who encountered this trade. For example, between 1772 and 1776 the Swedish doctor Anders Sparrman met ‘newly captured’ Khoe-San on a farm in the lower Seacow Valley (Sparrman 1785a: 354). He also met an elderly group of Khoe-San who complained that all of their young people were stolen by Europeans, so that now they had to look after themselves and their livestock (Sparrman 1785b: 20). Later on, Sparrman (1785b: 31) encountered a ‘Hottentot’ who was given a gun by the farmer he worked for to go and steal Bushmen to work as slave labourers. Twenty years later John Barrow (1801: 235–236) related how:

‘such of the Bosjesmans as should be taken alive in the expeditions made against them, were to be distributed by lot among the Commandant and his party, with whom they were to remain in a state of servitude during their lives.’

Yet it was not only the European settlers who participated in this system of kill or capture. Groups of Korana and Bergenaars, themselves of mixed ancestry comprising Khoe, San, slaves and Europeans, were known to raid Khoe-San kraals and sell captives as a cheap labour force to the Boers living on the frontier (Leśniewski 2010: 16). The Bergenaars grew in martial strength in the late 1820s as interior African slave traders, taking people from groups of African farmers and hunter-gatherers (and, presumably, herders) whom they bartered with European settlers, which was illegal under colonial law, for arms and ammunition. Their numbers grew as they were continually joined by ‘outlaws and runaways from the Colony’ (Philip 1828 Volume 2: 298).

From the eighteenth until the mid-nineteenth centuries, it seems that Khoe-San were increasingly considered as property as opposed to employees. As Theal (1904a: 207) notes, in 1825 the slave rebel leader Galant described his collaborators, Admiral Slinger, Moses and Andries as Khoe-San, but also said that they ‘were people belonging to’ the farmer Piet van der Merwe. Those able to escape this tightening net entered into various states of marronage, often returning to steal from the farms on which they had been employed. Owing to such stock theft in 1811, Khoe-San labelled ‘Banditti’ by the Commission of Circuit (cf. Newton-King 1999: 63; Sinclair-Thomson 2020) were put in chains and forced to labour on public works in the Graaf-Reinet District (Theal 1901: 338). Eventually, the Khoe-San found themselves in a situation where they were treated worse than legal slaves. This is exemplified in the drunken comments, to a slave, of a farmhand who had killed a Khoe labourer — that while the Khoe had no rights, the slave at least had commercial value and ought therefore to be spared (Ross 1983: 43–44).

The time period with which we are concerned, namely the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, is one in which travellers frequently described encounters with runaway slaves who had turned to banditry (cf. Hobsbawm 1969). Importantly for our purposes, these numerous accounts describe runaway slaves appearing within groups of indigenes, as well as the mixing between these peoples. In 1797, Barrow’s party was joined by three runaway slaves and three Khoe-San whom they found in a notorious raiding spot (Barrow 1801: 96). In the nineteenth century, a ‘Bushman’ named Dragoener was known to have runaway slaves within his group of bandits, raiding settler farms in the Winterberg region (Pringle 1835: 98). While travelling through the Lower Roggeveld in the first decade of the nineteenth century, Lichtenstein (1928: 125–126) heard of a settler family who had been killed by their slaves who were working together with ‘Bushmen’ and suggested that the slave had sought revenge after being mistreated. Travelling through the same region in 1811, Burchell (1822: 258) learnt that farmers often abandoned their houses and took everything with them to avoid being robbed by ‘runaway slaves or Vagabond Hottentots’. A similar circumstance was observed by Thompson (1967: 46) in the Sneeuberg in 1823, where he learnt that runaway slaves and ‘Bushmen’ bandits robbed travellers.

Although the circumstances and strategies of escape were varied, in most cases the fugitives joined groups of indigenous or mixed outlaws. In these situations we must always ask ourselves what options were open to such individuals (Challis 2012). Gener- ally, the best recourse was to flee from the settler farms in order to take advantage of them, i.e. to be ‘compelled to adopt a parasitic existence’ (Penn 1999: 81). Thus, we find recorded examples of bandit groups hiding out in mountain refuges within striking distance of farms for livestock raids. In some instances, the locations of the hideouts of these bandit groups are recorded. These include the Winterberg (Pringle 1835), the Bamboesberg (Barrow 1801), the Stormberg (Collins 1959) and the Drakensberg (multiple primary sources in Wright 1971). These locations typically offer expansive views, thereby allowing bandits to keep an effective lookout for any would-be pursuers (cf. Bernard 2008: 338 for North American Chumash sites of a similar nature). Importantly, these areas also contain rock art that can be reliably dated to the time period under discussion and provides us with the reverse gaze (Ouzman 2003; Challis 2018), a counter- point to the written record (cf. Paterson 2012).

Evidence pointing toward the authorship of the images in question stems from several converging factors. First, there is the existence of heterogeneous banditti, as already out- lined. Second, there are specific locations mentioned by colonial authorities as the haunts of those groups, sometimes naming particular people in particular named places. Third, when we visit rock shelters in these locations and find images of horses and guns we know, with a relative degree of accuracy, that they can only have been produced within a certain time frame: beginning with the arrival of these elements with European settlement and ending with the disappearance of the bandits. Fourth, the paintings themselves are not only mixed — some brush-painted (in different techniques), some finger painted — but also display subject matter that pertains to spiritual beliefs concerning escape and protective power. We now turn to these factors in more detail.

Painting from the southern Maloti-Drakensberg rock-shelter: A Traditional Corpus eland depicted with shaded polychrome (oldest dated c. 3000 cal. BP; Bonneau et al. 2017);

That there are rock paintings at all suggests that these bandit groups consisted of at least some Khoe-San members or were, alternatively, drawing on the cultural practices of the Khoe-San as producers of rock art (Blundell 2004; Challis 2012, 2014, 2016). Colonial-era rock art — arguably made by multi-ethnic groups — appears to have some reverence for its Khoe-San antecedents in some subject matter. We do, however, see something of a disconnect between this art and that of the earlier Khoe-San painters (sensu Loubser and Laurens 1994; Challis and Sinclair-Thomson in press). As a result of this disconnect, the painting technique is notably ‘rougher’ and less refined; there is a drop in pigment quality and the manner of depiction is somewhat simplified and performed with a smaller colour palette (Figure 3). We argue that these changes came about as a result of contact, experienced in a variety of iterations that included intermixing in both genetics and ideology, with incoming populations. Change also probably occurred as groups lost their access to traditional resources and the knowledge networks necessary to create images akin to those painted prior to contact.

Painting from the southern Maloti-Drakensberg rock-shelter: An eland depicted in poster-like block colour, likely painted post-contact.

The location of a band of mixed outlaws comes to us from the record of the famous 1820 settler, poet and abolitionist Thomas Pringle (1840: 77), who noted that by 1824:

‘A band of native banditti had for some time past established themselves among the rocks and woods of the Neutral Ground, composed partly of wild Bushmen from the north-east, partly of tame Bushmen (as they are termed), who had absconded from the service of the Boors; and they were rendered more dangerous and desperate by having been recruited by one or two runaway slaves, and by several deserters from the Cape Corps, who possessed fire-arms.’

The ‘Neutral Ground’ of which Pringle wrote included, at the time, the valley of the Mankazana River in today’s Eastern Cape Province (Pringle 1840: 77). We recently undertook fieldwork in this area where we found rock paintings of horses and guns that can be reliably dated to approximately when Pringle was writing (i.e. from the late eighteenth century, when Europeans first settled the region, until the early nineteenth century, when banditry ceased in the Winterberg). That groups of bandits on the borders of the Cape Colony created rock paintings is well attested (Blundell 2004; Ouzman 2005; Challis 2008, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018; Sinclair-Thomson in press), yet these particular paintings have not previously been studied within this context. What makes these images all the more compelling as examples of the archaeology of slavery (cf. Stahl 2008: 38) is the historical testament of Pringle reproduced above.

That heterogeneous groups of bandits painted rock art depictions of cattle raids suggests that raiding was a fundamental concern for these groups. If we have learnt anything from the past several decades of southern African rock art research, it is that images are not the mere depictions of what the artists saw around them. Rather, they are representations of what ritual specialists see while travelling through the spirit world, access to which is achieved by altered states of consciousness (Lewis-Williams 1982). In the case of bandit groups, the ritual specialist often performed the role of war-doctor. This position was accorded great importance during times of conflict among many southern African societies (Challis 2012, 2014; Sinclair-Thomson and Challis 2017; and see also below). Consequently, we ought not to view paintings of raids as images of actual events, recorded by artists either for fancy or historical documentation. If paintings can be seen to be both a record of the process, and as a part of the process, undergone by ritual specialists, then we could do worse than look at the role of ritual specialists during times of conflict.

In a recent paper (Sinclair-Thomson and Challis 2017), we examined beliefs across southern Africa concerning the magical ability to influence the trajectory of projectile weapons. This belief has been linked specifically to paintings depicting firearms (Sin- clair-Thomson 2019; cf. Robinson 2013 for examples of ‘polyvalent metaphors’ in the rock art of south-central California). It is argued that the ritual specialists within these groups of bandits would also have exercised this power when in situations of conflict. The creation of images on rock was one such iteration of this practice. Individuals who claimed these supernatural abilities would either have occupied prominent positions within, or headed, these groups and would likely have been sought out by runaway slaves in the hope that they might be offered protection from punitive expeditions (cf. Etherington 2001). At the same time, fugitives would have supplied the bandit group with intelligence concerning their former places of occupation which could have been used to ensure a successful raid (Barrow 1801: 236; cf. Marks 1972).

Indeed, the notion of supernatural protection was likely at the core of the creation of paintings by bandit groups. Southern African rock art research (Jolly 1986; Lewis-Williams 2019) demonstrates that the making of rock art was the domain of ritual specialists. These are the very people who, in their role as war-doctors, also supplied traditional medicines to ensure protection in dangerous situations, including cattle raids and the flight from servitude (Challis 2014, 2018). In one account from the late nineteenth century, the traveller Theophilus Hahn was explicitly told by his Khoekhoe guides that they painted on stone, and on themselves, as a form of protection (Hahn 1881: 140). These beliefs in supernatural protection were cross-cultural and were particularly pertinent to slaves, both immigrant and indigenous. For example, a group of Islamic Malay slaves who fled the Cape Colony and attempted to reach the Xhosa were caught with ‘talismans’ that were meant to guarantee a successful escape. These had been supplied by an imam in the Cape (Ross 1983: 20–21). Immigrant slaves would also approach local Khoe-San to supply them with traditional medicines to ensure supernatural effects, such as the case of a slave from Bengal who acquired some ‘beans’ from a Khoe-San man to stop other slaves from harassing him (Ross 1983: 46). This example is highlighted by Ross (1983: 46) as demonstrating that slaves would approach those most likely to be able to assist them, which we suggest was a common theme among the vast majority of desertions. That is to say, if immigrant slaves were to join a group of Khoe-San bandits, they might recognise the necessity and meaning of painting as a form of protection among other ritual observances.

Paintings made in the nineteenth-century Maloti-Drakensberg by creolised AmaTola ‘Bushmen’. In their dances, derived from the San trance dance, they accessed the protective powers of the baboon, taking on its features and qualities.

Finger-painted and fine-line horses from the shelter along the Mancazana River that attest to the mixed nature of these bandit groups as described by Pringle (1840: 77). Scale is indicated by the width of the finger painting.

Another group of ‘Bushmen, Hottentots and runaway slaves’ is recorded in an earlier reference to raiding on the eastern Cape frontier. In fact, it was hypothesised (Challis 2012) that this region was where the Tola-type creolised bands first formed, as loose- knit multi-ethnic fugitives. Survey of the Mancazana area undertaken to test this hypothesis revealed rock shelters that exhibit precisely these phenomena: images of horses, cattle and baboons.

Finger-painted and fine-line horses from the shelter along the Mancazana River that attest to the mixed nature of these bandit groups as described by Pringle (1840: 77). Scale is indicated by the width of the finger painting. Note the baboons painted beneath the black horse.

Further into the hinterland, as if to mark the fighting retreat of bandit groups as the colonial frontier expanded, we discover sites in mountain rock shelters of the Stormberg and the neighbouring Zuurberg that exhibit yet more features of an indigenous resistance idiom. In the Zuurberg, for instance, is a rock shelter in which are painted images of people with horses and guns (Figure 6a), as well as baboons (yet painted very differently) and ostriches (Figure 6b).

The ostrich was recognised by Khoe-San groups as being particularly adept at escaping from danger. It could outrun most predators and leap over the nets of hunters (Low 2009: 72). Khoe-San would, and still do, tie the tendons from ostrich legs to their own legs to stop fatigue (Low 2009: 72). Ostrich eggshell was also recognised as a medicine that could be ground up and consumed as a fortifying tonic (Engelbrecht 1936: 186). That this bird, as well as ritual specialists transforming into it (Figure 6b), appears in the art of bandits illustrates that these groups were drawing on its powers to ensure their own escape, whether from their former captors or pursuing commandos following raids.

Painting from a shelter in the Zuurberg showing: Figures with guns, one mounted.

Painting from a shelter in the Zuurberg showing: Ostrich and baboon therianthropes that attest to the artists’ ‘drawing on’ these animals’ potency and qualities for escape and protection.

- 1. Our deinition of ‘slaves’ is explained presently.

- 2. Nomenclature deriving from High Dutch, Cape Dutch, Farm Dutch (Boeretaal) and Afrikaans all ultimately relates to Dutch occupation of the Cape in 1652 and subsequent colonisation. British colonists after 1795 adopted many such words, for example Boschiesman from which Bushman is derived.

- 3. The progeny of relations between the immigrant and indigenous Khoe-San slaves were known as ‘Bastaard-Hottentots’ (Newton-King 1999: 117). As children, ‘Bastaard-Hottentots’ were usually raised similarly to their parents in unfree labour, from which they were legally entitled to leave after a certain period. This allowance of freedom, however, was not always observed (Penn 2005: 20) — yet further evidence of conditions from which one might wish to escape.

- 4. The exact number of slaves from each region is uncertain owing to missing records coupled with illegal slave dealing not sanctioned by the VOC (Armstrong and Worden 1989: 115). What is known is that during the period 1680–1731 48.5% of the 3283 slaves imported to the colony were from Madagascar, while 31.6% were from India and Indonesia. 19.8% were not identified (Armstrong and Worden 1989: 121).

- 5. Although pejorative, this term is useful for illustrating the interactions between immigrant and indigenous slaves.

- 6. The precise number of sites is at present unknowable because survey work is still very piecemeal. In our fieldwork in the Stormberg region, we found four painted rock shelters and in the Winterberg region a further five. Two additional shelters were found in the Windvogelberg to the east of the Winterberg, along with a single shelter in the Zuurberg. There are probably many more. This is not even taking into account the 100+ sites with horses in the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains.

We wish to thank our colleagues at the Rock Art Research Institute and Geoff Blundell at the KwaZulu-Natal Museum. We are grateful to Will and Jill Pringle, Denham Pringle and Andrew Pringle, Louw de Beer, Mr and Mrs Bennett and Bruce Rodney for accommodating us on our fieldwork excursions. We thank Jeremy Hollmann and Pieter Jolly for comments on drafts of this article. We further thank the University of the Witwatersrand library for the scanned image of Júli and sculptor Barry Jackson, as well as Sarah Haines at the National Heritage Project Company for the image of Louis van Mauritius. We thank the editors for their invitation to attend the SAA conference session in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 2019 and their attention to detail on our manuscript. Any omissions or errors are entirely our own.

Brent Sinclair-Thomson is a PhD candidate at the Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. He has a special interest in the rock art of mixed-ethnic bandit groups and how this medium relates to resistance to colonialism, as well as how the interaction between different ethnic groups are manifested and reflected in rock art, particularly the ‘indigenising’ of the gun.

Sam Challis is Head and Senior Researcher at the Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand. His focus is on the interaction between hunter-gatherers, pastoralists and farmers, as well as Europeans, as expressed in rock art around the world. His DPhil focused on the acquisition of horses by creolised raider groups in the nineteenth-century, and his current research pro- gramme in Matatiele aims to redress the imbalance of this neglected former-apartheid region while training local community Field Technicians.

Allen, R. 2010. “Satisfying the “want for labouring people”: European slave trading in the Indian Ocean, 1500–1850.” Journal of World History 21: 45–73.

Alleyne, M. 2005. The Construction and Representation of Race and Ethnicity in the Caribbean and the World. Kingston: University of West Indies Press.

Alpers, E. 2003. “Flight to freedom: escape from slavery among bonded Africans in the Indian Ocean world, c. 1750–1962.” Slavery & Abolition 24(2): 51–68.

Armstrong, J. and Worden, N. 1989. “The slaves, 1652–1834.” In The Shaping of South African Society, 1652–1840, edited by R. Elphick and H. Giliomee, 109–183. Cape Town: Longman.

Barnard, A. 1992. Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barnard, A. 2008. “Ethnographic analogy and the reconstruction of early Khoekhoe society.” Southern African Humanities 20(1): 61–75.

Barrow, J. 1801. An Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa, in the Years 1797 and 1798, Volume 1. London: T. Cadell and W. Davies.

Bernard, J.L. 2008. “An archaeological study of resistance, persistence, and culture change in the San Emigdio Canyon, Kern County, California.” PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Besten, M.P. 2011. “Envisioning ancestors: staging of Khoe-San authenticity in South Africa.” Critical Arts 25: 175–191.

Blundell, G. 2004. Nqabayo’s Nomansland: San Rock Art and the Somatic Past. Uppsala: Uppsala University Press.

Bonneau, A., Pearce, D.G., Mitchell, P.J., Staff, R., Arthur, C., Mallen, L., Brock, F. and Higham, T.F.G. 2017. “Direct dating reveals earliest evidence for parietal rock art in southern Africa.” Antiquity 91: 322–333.

Burchell, W. 1822. Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa. London: Longman.

Challis, S. 2008. “The impact of the horse on the Amatola ‘Bushmen’: new identity in the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains of southern Africa.” DPhil. diss., University of Oxford.

Challis, S. 2012. “Creolisation on the nineteenth-century frontiers of southern Africa: a case study of the AmaTola ‘Bushmen’ in the Maloti-Drakensberg.” Journal of Southern African Studies 38: 265–280.

Challis, S. 2014. “Binding beliefs: the creolisation process in a ‘Bushman’ raider group in nineteenth- century southern Africa.” In The Courage of //Kabbo: Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the Publication of Specimens of Bushman Folklore, edited by J. Deacon and P. Skotnes, 246–264. Johannesburg: Jacana.

Challis, S. 2016. “Re-tribe and resist: the ethnogenesis of a creolised raiding band in response to colonisation.” In Tribing and Untribing the Archive: Identity and the Material Record in Southern KwaZulu-Natal in the Late Independent and Colonial Periods, edited by C.

Hamilton and N. Leibhammer, 282–299. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Challis, S. 2018. “Creolization in the investigation of rock art of the colonial era.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art, edited by B. David and I. McNiven, 611–633. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Challis, S. and Sinclair-Thomson, B. in press. “The impact of contact and colonization on the Indigenous worldview, rock art and history of southern Africa: ‘The Disconnect’.” Current Anthropology.

Collins, R. 1959. “Journal of the tour to the north-eastern boundary of the Orange River and the Storm Mountains by Col. Collins in 1809.” In The Record, or a Series of Official Papers Relative to the Condition and Treatment of the Native Tribes of Southern Africa, edited by D. Moodie, 1–38. Cape Town: A.A. Balkema.

Crais, C. 1990. “Slavery and freedom along a frontier, the Eastern Cape, South Africa: 1770–1838.” Slavery & Abolition 11(2): 190–215.

Der, L. and Fernandini, F. (eds). 2016. Archaeology of Entanglement. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

Engelbrecht, J. 1936. The Korana. Cape Town: Maskew Miller.

Etherington, N. 2001. The Great Treks: The Transformation of Southern Africa 1815–1854. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Giliomee, H. 1992. “The Eastern Frontier, 1770–1812”. In The Shaping of South African Society, 1652–1840, edited by R. Elphick and H. Giliomee, 421–470. Cape Town: Longman.

Hahn, T. 1881. Tsuni-i i Goam: The Supreme Being of the Khoi-Khoi. London: Trübner & Company.

Hall, S.L. and Mazel, A.D. 2005. “The private performance of events: colonial period rock art from the Swartruggens.” Kronos 31: 124–151.

Henry, L. 2010. “Rock art and the contested landscape of the north Eastern Cape, South Africa.” MA diss., University of the Witwatersrand.

Hobsbawm, E. 1969. Bandits. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Jolly, P. 1986. “A first generation descendant of the Transkei San.” South African Archaeological Bulletin 41: 6–9.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1982. “The economic and social context of southern San rock art.” Current Anthropology 23: 429–449.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 2019. Image-Makers: The Social Context of a Hunter-Gatherer Ritual. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lesniewski, M. 2010. “Guns and horses, c. 1750 to c. 1850: Korana — people or raiding hordes?” Werkwinkel: A Journal of Low Countries and South African Studies 5(2): 11–26.

Lichtenstein, H. 1928. Travels in Southern Africa in the Years 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806. Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society.

Lightfoot, K. and Martinez, A. 1995. “Frontiers and boundaries in archaeological perspective.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 471–492.

Loubser, J.N.H. and Laurens, G. 1994. “Depictions of domestic ungulates and shields: hunter/gatherers and agro-pastoralists in the Caledon River valley area.” In Contested Images: Diversity in Southern African Rock Art Research, edited by T.A. Dowson and J.D. Lewis-Williams, 83–118. Johannesburg; Witwatersrand University Press.

Low, C. 2009. “Birds in the life of KhoeSan, with particular reference to healing and ostriches.” Alternation 16(2): 64–90.

Marks, S. 1972.” Khoisan resistance to the Dutch in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.” Journal of African History 13: 55–80.

Mallen, L. 2009. “Rock art and identity in the north Eastern Cape Province.” MA diss., University of the Witwatersrand.

McMaster, G., Lum, J. and McCormick, K. 2018. “The entangled gaze: indigenous and european views of each other.” ab-Original, Journal of Indigenous Studies and First Nations and First Peoples’ Cultures 2(2): 125–140.

Morton, F. 1992. “Slave-raiding and slavery in the western Transvaal after the Sand River Convention.” African Economic History 20: 99–118.

Napier, E. 1849. Excursions in Southern Africa: Including a History of the Cape Colony, an Account of the Native Tribes etc. London: William Shoburl.

Newton-King, S. 1999. Masters and Servants on the Cape Eastern Frontier, 1760–1803. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ouzman, S. 2003. “Indigenous images of a colonial exotic: imaginings from Bushman southern Africa.” Before Farming 2: 239–256.

Ouzman, S. 2005. “The magical arts of a raider nation: central South Africa’s Korana rock art.” South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 9: 101–113.

Paterson, A. 2012. “Rock art as historical sources in colonial contexts.” In Decolonising Indigenous Histories: Exploring Prehistoric/Colonial Transitions in Archaeology, edited by M. Oland, S.M. Hart and L. Frink, 66–85. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Penn, N. 1999. Rogues, Rebels and Runaways: Eighteenth-Century Cape Characters. Cape Town: New Africa Books.

Penn, N. 2005. The Forgotten Frontier: Colonist and Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern Frontier in the 18th Century. Cape Town: Juta and Company Ltd.

Penn, N. 2013. “The British and the ‘Bushmen’: the massacre of the Cape San, 1795 to 1828.” Journal of Genocide Research 15: 183–200.

Philip, J. 1828. Researches in South Africa. London: James Duncan.

Pringle, T. 1835. Narrative of a Residence in South Africa. London: Edward Moxon.

Robinson, D. 2013. “Polyvalent metaphors in south-central California missionary processes.” American Antiquity 78: 302–321.

Ross, R. 1983. Cape of Torments: Slavery and Resistance in South Africa. Abingdon: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Sinclair-Thomson, B. 2019. “Indigenising the gun–rock art depictions of firearms in the Eastern Cape, South Africa.” Time and Mind 12: 121–135.

Sinclair-Thomson, B. 2020. “Trouble on the Tarka: the rock art of bandit groups on the Cape Colony’s eastern border.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-020-00556-6.

Sinclair-Thomson, B. and Challis, S. 2017. “The ‘bullets to water’ belief complex: a pan-southern African cognate epistemology for protective medicines and the control of projectiles.” Journal of Conflict Archaeology 12: 192–208.

Sparrman, A. 1785a. A Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope: Towards the Antarctic polar Circle, and Round the world: but Chiefly into the Country of the Hottentots and Caffres, from the Year 1772, to 1776 Volume 1. London: GGJ and J. Robinson.

Sparrman, A. 1785b. A Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope: Towards the Antarctic polar Circle, and Round the world: but Chiefly into the Country of the Hottentots and Caffres, from the Year 1772, to 1776 Volume 2. London: GGJ and J. Robinson.

Stahl, A.B. 2008. “The slave trade as practice and memory. What are the issues for archaeologists?” In Invisible Citizens: Captives and Their Consequences, edited by C. Cameron, 25–56. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Theal, G. (ed.). 1901. Records of the Cape Colony Volume 8, from March 1811 to October 1812. London: Public Record Office.

Theal, G. (ed.). 1904. Records of the Cape Colony Volume 20, from February to April 1825. London: Public Record Office.

Thompson, G. 1967. Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa. Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society.

Worden, N. 1982. “Violence, crime and slavery on Cape farmsteads in the eighteenth century.” Kronos 5: 43–60.

Wright, J.B. 1971. Bushman Raiders of the Drakensberg, 1840–1870: A Study of Their Conflict with Stock-Keeping Peoples in Natal. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation