Aron Mazel

Newcastle University and University of the Witwatersrand

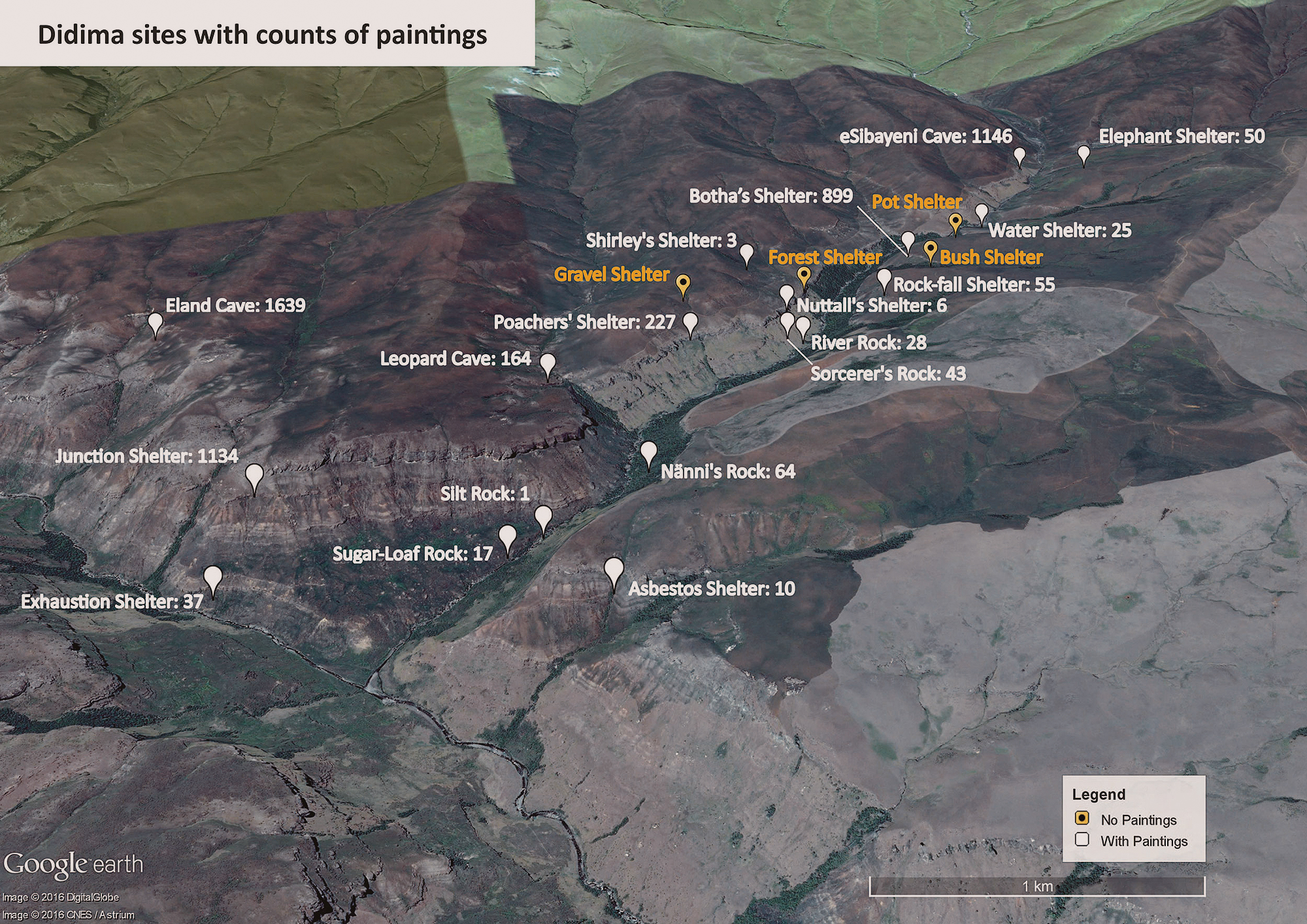

uKhahlamba-Drakensberg (stippled), with Didima Gorge and Cathedral area (outlined).

Pager’s (1971) redrawings show that there may be about 50 sheep paintings, concentrated on one panel (Figure 3). Only one other sheep painting has been identified in the gorge (eSibayeni Cave, Gavin Whitelaw, pers. comm., 2014), while another four sheep paintings have been recorded in the surrounding area. Hunter-gatherers, not only in the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg, but across southern Africa, appear to have incorporated sheep into their symbolic systems in which trance performances and visions were central. This is revealed by the sheep and associated paintings on the sheep panel by: (i), elongated sheep paintings, (ii), a sheep with two tails (Figure 4), (iii), the possibility that some of the sheep may be bleating, (iv), an animal emerging from the rock face (Figure 4), (v), an animal with bristles (Figure 4), (vi), an antelope-headed snake (Figure 5), and, (vii), animals that represent what Blundell (2004: 107) refers to as ‘indeterminate creatures that appear to be conflations of antelope and fat-tailed sheep characteristics’ (Figure 6).

Turning to baboons, Junction Shelter contains 49 of the 51 (i.e., 96%) baboon paintings recorded in the gorge (Pager 1971). Significantly, three of these paintings occur either on the sheep panel or close to it, while the remaining 46 were done on another panel. Almost all the other recorded 148 baboon paintings in the surrounding area occur relatively nearby and are within eight kilometres of each other in the lower Mhlwazini valley, of which Didima is a tributary.

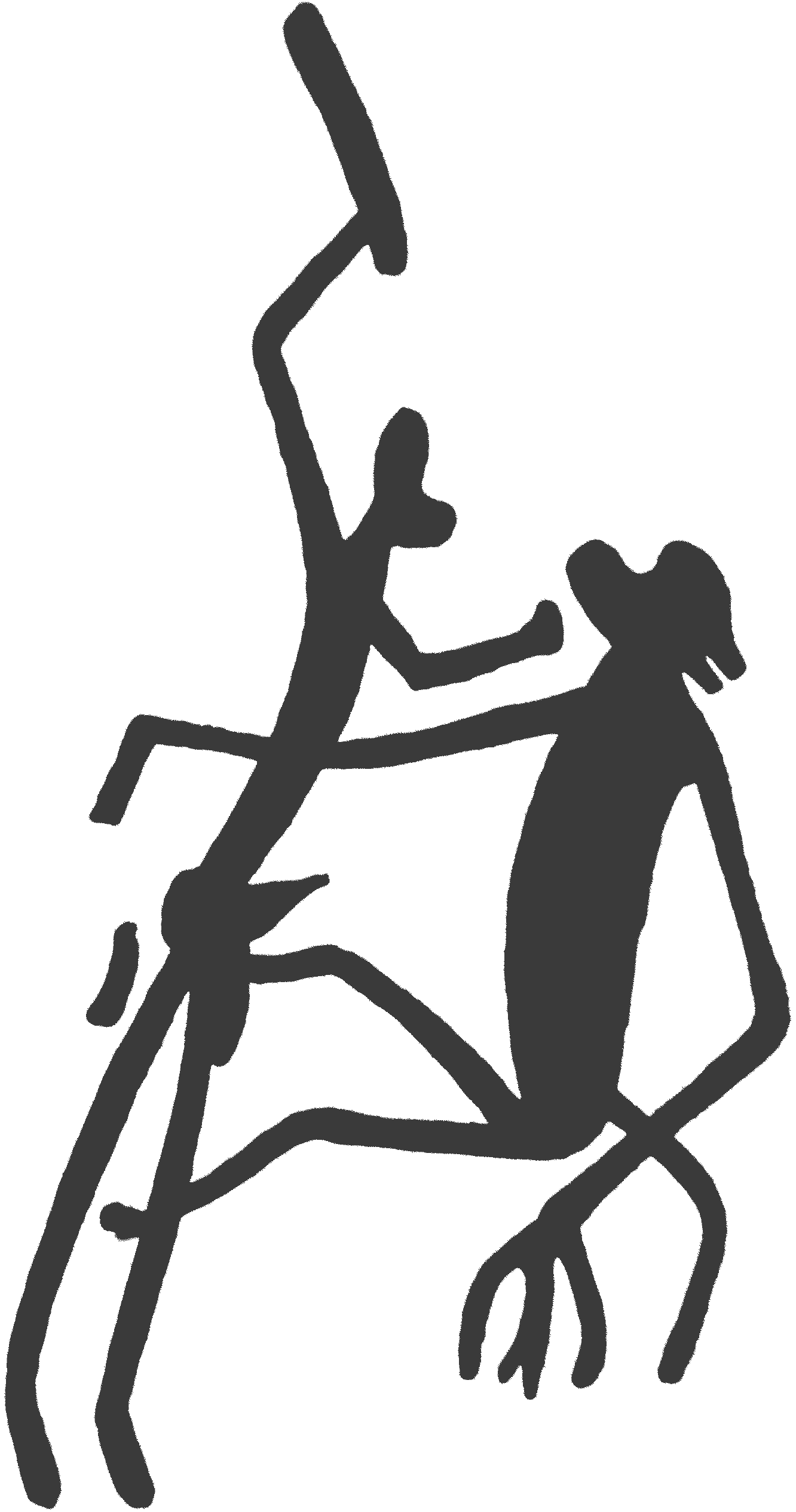

As with the sheep panel, a close connection exists between baboons and hunter-gatherer symbolic systems and trance performances and visions. This is reflected, for example, in an upright baboon figure with one of its arms appearing to reach towards its nose, which, if correct, represents what Lewis-Williams and Dowson (2000: 48) identify as a ‘repeated posture’ in hunter-gatherer rock art signifying people in trance ‘sniffling out sickness’. There is also a baboon with elongated arms and three exaggerated fingers (Figure 7). Mguni (2002) links digits to trance performance and altered states of consciousness. According to Challis (2012: 276), 19th century hunter-gatherers believed that baboons had powers of ‘defence or protection’, which included ‘supernatural abilities’ to cause mists, hide an armed force, and make an enemy forget things.

It has been suggested that the hunter-gatherers painted the sheep and baboon images around 2000 years ago when they experienced anxiety due to the movement of farmers and pastoralists into southern Africa. Up until then they had been the sole occupants of the subcontinent. This represented a major turning point in their history.

Junction Shelter: baboon figure, which Pager (1971a: 193) refers to having as having been thrown ‘off balance’ by a ‘pugilistic upper-cut’ from a human figure. Note the digits on the baboon’s left hand.

It is widely acknowledged that rock art sites were places of power and, as Whitley (1998:16) has noted, they were not ‘neutral backdrops’, but were ‘as symbolically important as the iconography’. Moreover, Taçon (1999: 37) has identified that places with ‘panoramic views or large vistas’ evoke feelings of ‘awe, power, majestic beauty, respect, [and] enrichment among them’ in humans. Taken further, he (1999: 41) has suggested that when practices occurred at the same place over extended periods, as is likely to have characterised Junction Shelter and indeed Didima Gorge, they become ‘increasingly symbolically charged, patterned and contextualized’, thus perpetuating ‘traditions of landscape experience and enrichment’.

Farmers would have been distant from the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg 2000 years ago. Their approaching presence on the southern African landscape, however, was probably felt by the mountain hunter-gatherers hundreds of kilometres away (see Mazel 2009 for a discussion of this). In contrast, the possibility exists that pastoralists, with their sheep, ephemerally occupied the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg at the time and might even have ventured up the Mhlwazini valley to Didima Gorge. If so, the bleating of their sheep would have been heard far and wide through the area, encouraging the hunter-gatherers to consider them powerful things, and therefore valuable to include in their symbolic systems, especially as ritual activities are important events for managing angst about perceived insecurity in small-scale societies.

In summary, Junction Shelter’s strategic location at the confluence of the Didima and Mhlwazini rivers in Didima Gorge, along with the meanings attributed to baboons and sheep in hunter-gatherer belief systems, may have been why the hunter-gatherers created this unique combination of imagery on its walls.

1 This article is a substantially condensed version of: Mazel, A.D. 2023. Sheep and baboon paintings in Junction Shelter: shedding light on the history of Didima Gorge and surrounding areas, South Africa. Beyond Boundaries: a Festschrift for Simon Hall. Southern African Humanities: 36, 33-60.

2 In the 1960s, Harald Pager (1971) recorded 3909 rock paintings in 17 rock shelters in Didima Gorge with Junction Shelter containing 1134 paintings, second only to eSibayeni Cave with 1146.

Blundell, G. 2004. Nqabayo’s Nomansland: San rock art and the somatic past. Uppsala: Uppsala University Press.

Challis, S. 2012. Creolisation on the 19th-century frontiers of southern Africa: a case study of the AmaTola ‘Bushmen’ in the Maloti-Drakensberg. Journal of Southern African Studies 38: 265–80.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. & Dowson, T.A. 2000. Images of power: understanding Bushman rock art. Johannesburg: Southern Book Publishers.

Mazel, A.D. 2009. Unsettled times: shaded polychrome paintings and hunter-gatherer history in the southeastern mountains of southern Africa. Southern African Humanities 21: 85–115.

Mazel, A.D. 2023. Sheep and baboon paintings in Junction Shelter: shedding light on the history of Didima Gorge and surrounding areas, South Africa. Beyond Boundaries: a Festschrift for Simon Hall. Southern African Humanities: 36, 33-60.

Mguni, S. 2002. Continuity and change in San belief and ritual: some aspects of the enigmatic ‘formling’ and tree motifs from Matopo Hills rock art, Zimbabwe. MA thesis, University of the Witwatersrand.

Pager, H. 1971. Ndedema: a documentation of the rock paintings of the Ndedema Gorge. Graz: Akademische Druck.

Taçon, P. 1999. Identifying ancient sacred landscapes in Australia. In: W. Ashmore & A. B. Knapp (eds), Archaeologies of landscape: contemporary perspectives. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 33–57.

Whitley, D. 1998. Finding rain in the desert: landscape, gender and far western North American rock-art. In: C. Chippindale & P. Taçon (eds), The archaeology of rock art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 11–29.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation