Exhibition organized by the National Museum and Research Center of Altamira (Spain)

Curator

Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

Independent Rock Art Researcher and Expert, Bhopal

Coordinator

Pilar Fatás

Museo de Altamira

India’s rock art is as varied as its vast territory. Moreover, the diversity of natural environments contributes to the chronological dispersion of the different manifestations of rock art. Nevertheless, much of this art has surprising similarities.

Indian rock art is not too well known because it is frequently found in deep jungles, which contributes to academic interest because its cultural and natural contexts have often been preserved. Thus, it becomes possible to discover the persistence of age-old traditions among local tribes that may have to do with rock art and explain some of its meanings.

History of the discoveries

Prehistoric rock art was first identified in India in 1867-68 by Archibald Carlleyle at Sohagihat in the Mirzapur district of Uttar Pradesh, who never submitted it for publication. Based on some of his field notes, V. A. Smith published Carlleyle’s work, which is the only extant record of his discovery. In the same time J. Cockburn started exploring Mirzapur area more systematically.

F. Fawcett discovered rock engravings in 1901 in the Edakkal cave in the Kozhikode district of Kerala, and in 1910, C. W. Anderson recognized the sites of Singhanpur in Chhattisgarh. D. H. Gordon identified the Pachmarhi rock paintings in the Mahadeo Hills in 1932, while K. P. Jayaswal identified rock engravings in a rock shelter at Vikramkhol in the Sambalpur district of what is now Odisha, in 1933.

Finally, Vishnu Shridhar Wakankar discovered Bhimbetka in 1957 near Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh, which has one of the largest concentrations of rock paintings in all of India. Dr. Wakankar said that he had been travelling along the hills by train when he noticed spectacular sandstone rock formations along the ridge. He became fascinated by them and the surrounding landscape. He descended from the train to explore and discovered Bhimbetka. This site was entered on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 2003.

Isolated rocks and cliff faces have occasionally been chosen for paintings but, in most cases, there is an overhang to protect them. In fact, any rocks with overhangs, from small ones a few metres across to long, huge cliffs, have been chosen for paintings.

Central India is the richest zone of prehistoric rock art in India. Most rock art sites are situated in the Satpura, Vindhya, and Kaimur Hills. These hills are formed from sandstone, which weathers relatively quickly to form rock shelters and caves. The diversity of flora and fauna is the greatest asset of this dense forest. In this respect, these hills were ecologically ideal for human occupation at least as early as the Mesolithic period (from 10,000 BC).

The animal species depicted in rock art were of great economic importance because of their food value. Rock paintings are a major source of our understanding of how their creators related to their physical, biological, and cultural environments. These people held beliefs and practices, as their descendants do now, that expressed a direct or indirect relationship with their environment.

Archaeological evidence for Central India is sparse. The oldest remains date to the beginning of the Mesolithic period (around 10,000 to 8000 BC). People were hunter-gatherers armed with bows and arrows for hunting. Their technology is characterized by the production of flint tools―flakes, points, crescents, triangles, trapezes―obtained by pressure knapping from cylindrical cores. These micro-tools were probably inserted into bone or wooden handles to make composite knives, arrowheads, or spearheads. Their presence in various shelters testifies to their occupation by Mesolithic people. The art found there was vivid, with scenes involving humans and wild animals, such as humpless bovids and wild boars, and filled with complex geometric patterns.

The transition to the Neolithic probably took place between 7000 and 5000 BC, with its attendant economic, techno-logical, and cultural changes. While agriculture, animal domestication, and ceramics made their appearance, hunting continued to play a central role in the means of subsistence. The art reflects these changes with the appearance of humpbacked bovids, the representation of activities both domestic (pottery) and agricultural (ploughing), and the depictions of huts.

The end of the Neolithic period and the appearance of metal (copper and then bronze) occurred around 2500 or 2000 BC without profoundly affecting the way of life. During this phase, the Harappan Civilization developed. In art, the first representations of chariots appear.

Metal age and historical period

The Mauryan Empire, between the fifth and second centuries BC, was contemporary with the spread of Buddhism. The period of the Early Middle Kingdoms highlights the Kushan Empire (first to third century AD), which had contact with China and the Roman Empire. The Gupta Empire of the fourth century corresponds to the Classical Period, and it is marked by development of the arts, interrupted by the invasions of the Huns. The Late Middle Kingdoms form the medieval period until the thirteenth century, when Turks and Afghans created the Sultanate of Delhi, which fell in 1398, allowing the Gonds Kingdoms to emerge.

Until AD 800, art was dominated by warriors, which testified to troubled times and danger. During the Late Historic or Medieval Period, from 800 to 1300, the chronology of the art was more able to be confirmed due to the presence of particular weapons (for example, sword styles have already been documented elsewhere).

Today, traditional ceremonies are still taking place in various painted shelters at Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Rajasthan. The persistence of such beliefs and ceremonies in the modern world is remarkable.

The diversity of animals and ways to represent them is much greater than what is found in European cave art. For example, nearly thirty different animal species were identified in rock art of Central India.

Humans are generally dominant and nearly always at least present, even among the earliest paintings. In their case, too, variety was the main characteristic, even if they seemed to have been given fewer details.

Indian rock art is well known for the multiplicity of signs, symbols, vulvas, cup marks, footprints, and handprints, both negative and positive, in its rock shelters. The subjects represented are varied and numerous. Depending on the periods and the areas, their relative proportions may change significantly.

The techniques used

Among the colours used, red, which comes from iron oxides such as haematite, was dominant during all periods. White, from a white clay like kaolin, has also been widely used. Yellow ochre is also commonly used. Other colours, such as green and black, are not as common. Paintings were made by rubbing the colour nodule, either wet or dry, using fingertips, twigs, and hair brushes, or by spraying with the mouth to make hand stencils. Engravings have also been found in a few rock art sites, but mainly in the states of Ladakh, Kerala, and Manipur.

Reliable dates for the paintings have not yet been determined, but dating attempts have been made by relying on the subjects represented, their superimpositions, and their styles. It has been hypothesized that some rock art (for example, the rare green paintings in the Raisen area of Madhya Pradesh was created during the Upper Palaeolithic era more than ten thousand years ago.

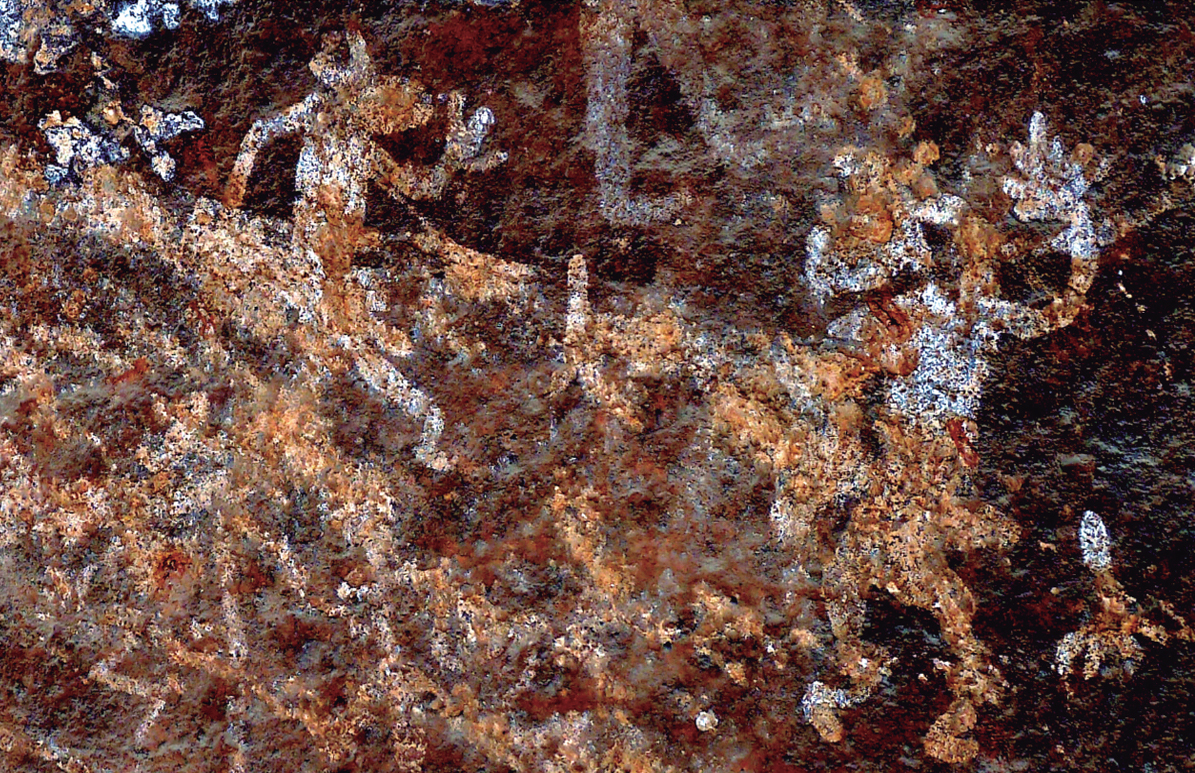

Ladakh in the Himalayas is one of the most elevated regions on earth and has been inhabited by humans since the Stone Age. The cultural heritage of Ladakh has long attracted the attention of various scholars, researchers, archaeologists, and explorers. The petroglyph engravings on rocks in the Ladakh region numbers in the thousands. Their ages range between five hundred and five thousand years ago. They are often found in valleys and along rivers, mainly near settlements and resting places. Various phases of evolution in the art are evident. The petroglyphs were primarily made on dark boulders coated with desert or rock varnish. The ancient artists used smooth, flat surfaces. Animal representations are abundant, as are hunting scenes and undetermined motifs.

The oldest Ladakh petroglyphs may be about five thousand years old. Animals are larger in size, signifying their importance as they provided the much-needed food and hides necessary to survival in the harsh climatic conditions of the cold Ladakh deserts. Hunting scenes of ibex, stags, and yaks are also depicted. With the arrival of Buddhism in the region some two thousand years ago, the subjects of petroglyphs shifted from hunting scenes and other symbols to Chortens (a kind of temple) and ibex, an animal blessed by the Lord Buddha. Of the petroglyphs that appear to belong to very recent times, none of the Chortens have rock varnish on them.

The majority of the Indus valley petroglyphs were made after the millennium turned from BC to AD. A large number of them testify to the emergence of Buddhism. Presenting the picture of a Stupa (a religious monument) was obviously considered a good deed. This accounts for the innumerable drawings of Stupas on rocks in the Indus Valley. Many are accompanied by an inscription from the first centuries AD.

The animal-god most respected and revered is the tiger. People worship him so that he will not harm their cattle. In the Bori area of Pachmarhi, we have found images of a man or a shaman riding a tiger. In the past, elders would meet outside the village, and the Bhagat (a religious devotee) would call the tiger with special chants. When the tiger came, he was offered chickens and coconuts. The elders would burn incense and pray to the tiger. This would ensure that their village would be safe from him. In April and October, they specifically worshipped the Goddess Kali. Then, they put on tiger masks, painted their bodies with stripes, put on tails, and became tigers.

Ibex, with long curved horns dropping onto their backs, were an important status symbol and often appeared on the rocks. A majority of ibex images are represented with male sexual organs. The ibex is a symbol of fertility according to pre-Buddhist religions. Some communities still worship during the Tibetan new year festival Losar by making offerings to the engraved ibex on the boulders, with a belief that it will lead to conception and bring a child to the family.

Snakes are also important. As with tigers, they are represented to prevent harm. In the Dharul area, we saw many sanctuaries to them, either on the roadside or in the jungle. In many areas of Central India, for the Naga Panchami Festival during the monsoon season, serpents are painted―on both sides of the door―with charcoal made from acacia wood. The charcoal powder is mixed with milk, water, or purified butter. Offerings (food, milk, coconut) made to the image are accompanied by prayers not to be harmed by snakes.

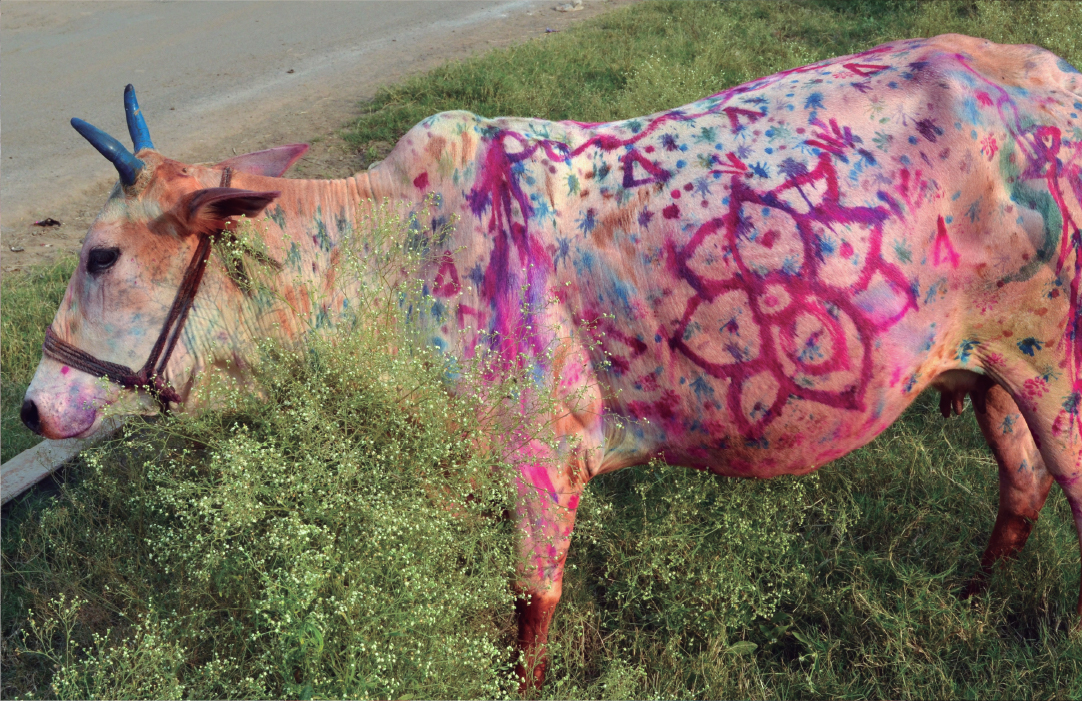

Cow and bull worship is also common among the tribes during the Diwali festival. They start preparing their cattle in the morning by washing, painting, and decorating them lavishly with handprints and symbols before feeding them special food. Early in the morning, the Shepherd will dance, make three rounds of the village, and do certain spells to safeguard the cattle from diseases. During the Pola Festival, they use terracotta bulls to show respect to their animals.

Horse sanctuaries near the roadside or in the jungle represent other local gods.

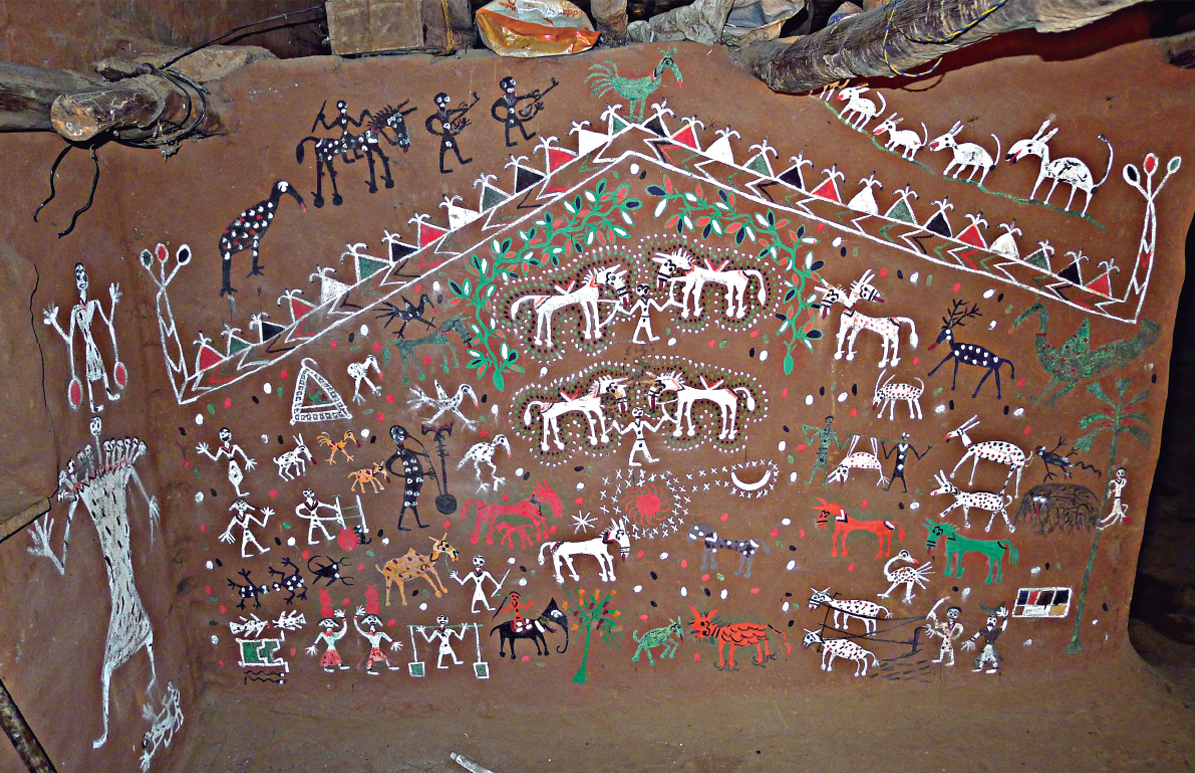

The paintings in shelters, like all other tribal arts, were obviously created within well-established traditions according to local myths and cultural practices. Also, they told or supported stories as a function of the events of the period (for example, war images). All of this did not prevent the painted shelters from maintaining a propitiatory role and being ceremonial places. This still goes on today, as we have recently discovered. Painted rock shelters have been converted into sanctuaries.

The importance and power of various animals, as well as their value as status symbols (horses, elephants), the role of trees, the sun and the moon, and the geometric signs that accompany all the major events in people’s lives are central to the profound meanings of both rock art and tribal art. The funerary pillars of the Korku, Gondi, Bhil, and Muria people are always carved or painted with a variety of animals. Such examples can be compared to representations of animals in local rock art.

Red dots and handprints are ubiquitous for their protective function. Red, white, and, less frequently, yellow hand stencils and footprints are a particular motif in the rock art and tribal art of Central India.

Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira. Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte

Subdirección General de Museos Estatales. Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte

Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak | Investigadora independiente y experta en arte rupestre | Independent Rock Art Researcher and Expert, Bhopal

Pilar Fatás | Museo de Altamira

Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

Vishnu Shreedhar Wakankar

J. Cockburn

F. Fawcett

C.W. Anderson

D.H. Gordon

Maricer González Museo de Altamira

Ana López Pajarón (Museo Nacional de Antropología)

Nexo

Serisan

SIT

Correduría: Poolsegur

Aseguradora: Scor Europe S.E.

Indian Army for Exploring Ladakh area

The Forest Department of Madhya Pradesh State

The Forest Department of Chhattisgarh State

The Culture Department (Raipur, Chhattisgarh)

Wakankar Research Institute (Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh)

INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art, Culture and Heritage) New Delhi

Fernando Sáez Lara, Ana López Pajarón y Ana Gracia Rivas (Museo Nacional de Antropología)

Vishnu Shreedhar Wakankar, Jean Clottes (France), Vivek Dhand (Chief Secretary, Raipur), Rakesh Chatuervedi (Chairman, Bio Diversity, Raipur), Amru, Lakshmi, Mohan, Netam, Prabhat, Bhodumal, Ajay, Jitendra, Sonam, Om Prakash, Luv Shekhawat, Abhimanyu, Kushagra and all people from different villages.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation