by María Isabel Hernández Llosas

Senior Researcher, CONICET, National Council for Scientific Research, Argentina

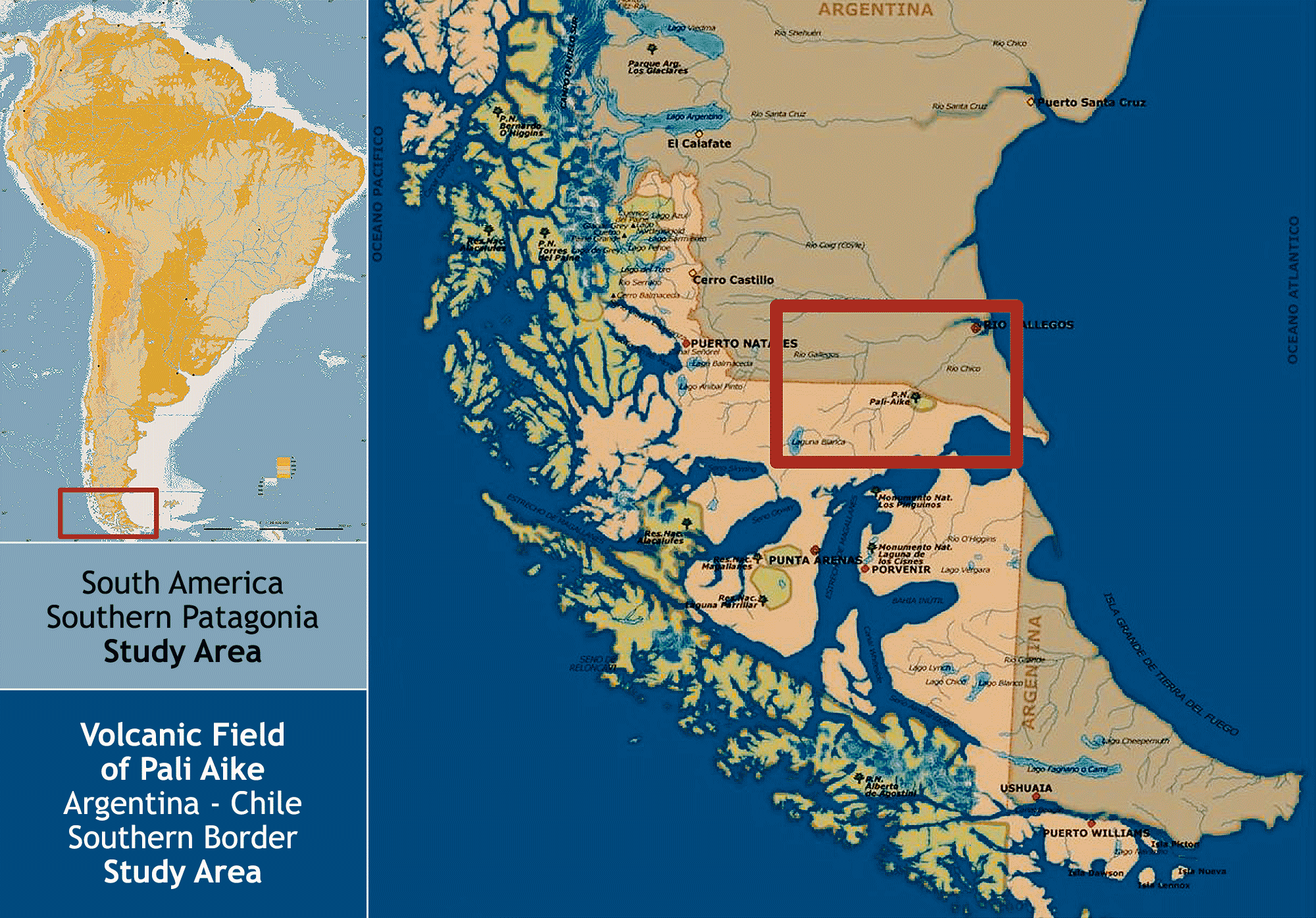

I was invited to participate in this particular project because, during the 1990's I performed an extensive recording of the rock art on the Argentinean side, specifically in the Rio Chico sector, and now this new project is devoted to study the rock art on both sides of the Argentina-Chile border in a broader regional context.

This area is known as the 'Pali Aike Volcanic Field', located on the southern edge of the Patagonian desert in both countries - Argentina (Province of Santa Cruz) and Chile (Province of Magallanes).

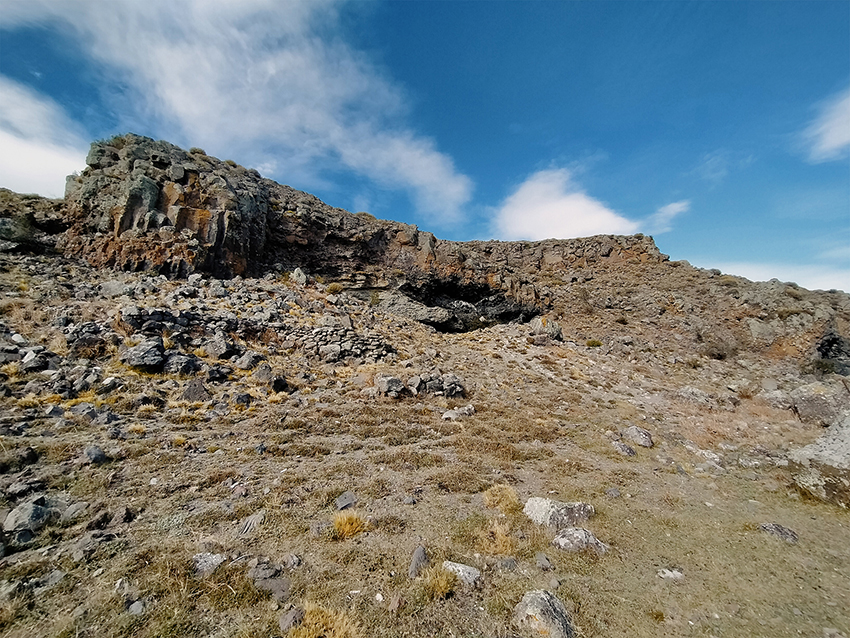

The singularity of this region is its environment, a cold windy desert with a particular topography characterized by the volcanic field, crossed by important rivers which give support to a great variety of birds, mammals (mainly guanacos and its predators, like pumas and foxes) and a scarce but sufficient vegetation to sustain them. This particular landscape was the territory of hunter-gatherers for millennia, and they left important rock art sites, which happen to be the most austral rock art manifestations of the world, in an area where until recently, and despite the early researches, the rock art is still very little known.

The most frequent visual aspects of this rock art is the predominance of abstract designs, mostly painted in red and to a lesser extent black and white, showing a high morphological and technical variability, with a chronology estimated, on relative bases and some indirect radiocarbon dating, around 2,000 years ago within the Late Holocene.

Recently, other designs have been discovered, corresponding to figurative representations of guanacos (south american wild camelid) with over-sized bellies, in this case engraved, whose shapes are similar to others found hundreds of kilometers away to the north. These motifs are not only novel for the area but also indicate they could correspond to earlier moments of the human settlement in southern Patagonia (Middle Holocene, ca. 5000 - 6000 years BP), suggesting that rock art in the extreme south of Patagonia would reach a greater temporal depth than the one currently assumed (this recording was done in previous field works, within the project 'Arqueología del valle del río Chico e interfluvio Gallegos-Chico, Campo Volcánico Pali Aike. Nuevas técnicas y líneas de evidencia' financed by CONICET-PICT 2061, Argentina).

The necessity of recognizing the amplitude of the diversification of the abstract motifs, together with the study of new types of figurative motifs, sustain the importance of this new project and one main goal is to identify strategies of representation and cultural transmission in hunter-gatherer populations in an area considered as a marginal settlement.

The methodology focus on distributional aspects of the rock art sites, including digital surveys of already known sites together with surveys in search for new sites. This information will analyse different approaches, including morphological determinations, studies about variations in techniques, statistical analysis, and geometric morphometry. Excavations of specific sites and their soundings are also planned in order to get a better resolution in the dating and contextual associations between rock manifestations and other kinds of material evidence.

This project was expected to have two field seasons visiting both sides of the border. The first one was done in December 2019, and the second in March 2020. We were doing our work on the Chilean side first, with the intention of going back to the Argentinean side to finish the recording there. But, the COVID-19 caught us in the middle. In fact we were crossing the border hours earlier the same day the lockdown was declared in both countries, when international and internal borders were completely closed.

For us, coming from the field, the lockdown was unexpected and caught us in a very complicated situation. The uncertainty of our situation and the real possibility of being stuck in Rio Gallegos (the southern city in the Argentinean province of Santa Cruz) for at least two months, on our own, with hotels and other services closed, made the situation a nightmare. After several days of rapidly changing scenarios about what could happen with us, a distant possibility of a rescue flight by Aerolineas Argentinas appeared on the horizon, but we did not know until the very last minute if we could board that plane.

We finally were included on the flight and the way home was another adventure. Just to go from the place we were staying in Rio Gallegos to the local airport was like a terror movie: internal safe-passage, military retains, sanitary authorities dressed as astronauts controlling body temperature, which, if exceeded certain degrees, you were unable to board the plane.....and so on. When the plane took off, it was the only one in the air in the whole country. When we arrived at Buenos Aires Airport, another set of astronauts were waiting for us in the main trail. We could see that all the other aircraft there were stopped and parked in the lateral tracks, covered completely with plastic sheets.

Buenos Aires Airport was completely shut (not lights, no - of course - shops, nothing), only the carrousel with our luggage was working. When I got out I had already asked a taxi driver who I know to come and pick me up. He got a permit for me and for him to get out of there and get home. All the streets were deserted. We had to cross another military retain before we got the main street towards my place, where, again, there was nobody anywhere. Total desolation. The rules of the lockdown were, and still are, quite strict in this part of the World.

Being completely happy to have had the possibility to get back home, I still have a weird feeling: when we leave to the field the World was one, and coming back, the World was a completely different one. The fact that the situation is Global makes it more scaring. What will happen to the World, to our lives and ultimately to our rock art project in the southernmost end of South America?

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation