by Neville Agnew

Senior Principal Project Specialist - Getty Conservation Institute

Our society is time-obsessed. Perhaps it has long been so. Some cultures answer a question about the age of the world, stars, and life with the simple response ‘forever’ which from the standpoint of the duration of the existence of life on our planet is a good enough one. It is, however, not satisfying to the modern mind which wants a time – scale to impose order on events of the physical world. The puzzle and debates about the age of the earth gained momentum in the late 18th century when scientific methods began to be used by eminent persons. No longer was Bishop Ussher’s date for the creation acceptable in the European world – a clock was needed. Archaeologists want to be able to date events ‘securely’ and this can usually be done by linking sequences in excavations to known dates, much like dendrochronology, the science of dating by means of trees using the annual growth rings in the wood. But if no written record exists, as is usual with archaeological sites and rock art, and when the cultures that made the art no longer survive there is an impasse. Rock art is not excavated, it is simply there on the rock face, without stratigraphic context, which appears to be a reason for its neglect as a worthy discipline by archaeologists.

Ingenuity was applied to attempt estimates of the age of the world. Geology provides a relative clock – sedimentary rocks offer a partial answer: younger ones lie above older, ‘all the way down,’ except when they have been overturned, even inverted; but this was a clue of sorts, not an answer. From the thickness of sedimentary deposits, sometimes a mile or more thick, it was clear, at least to geologists, that the earth must be vastly older than received wisdom stated it to be. It was clear too that sedimentary rocks are secondary ones, derived from older rocks by natural processes of weathering, erosion, and deposition. And under the sediments generally lie metamorphic and igneous rocks and they must be older yet. There was the problem also of fossils and the mystery of marine fossils, some species are still alive today like certain mollusks, found high in the Andes, as noted by Darwin.

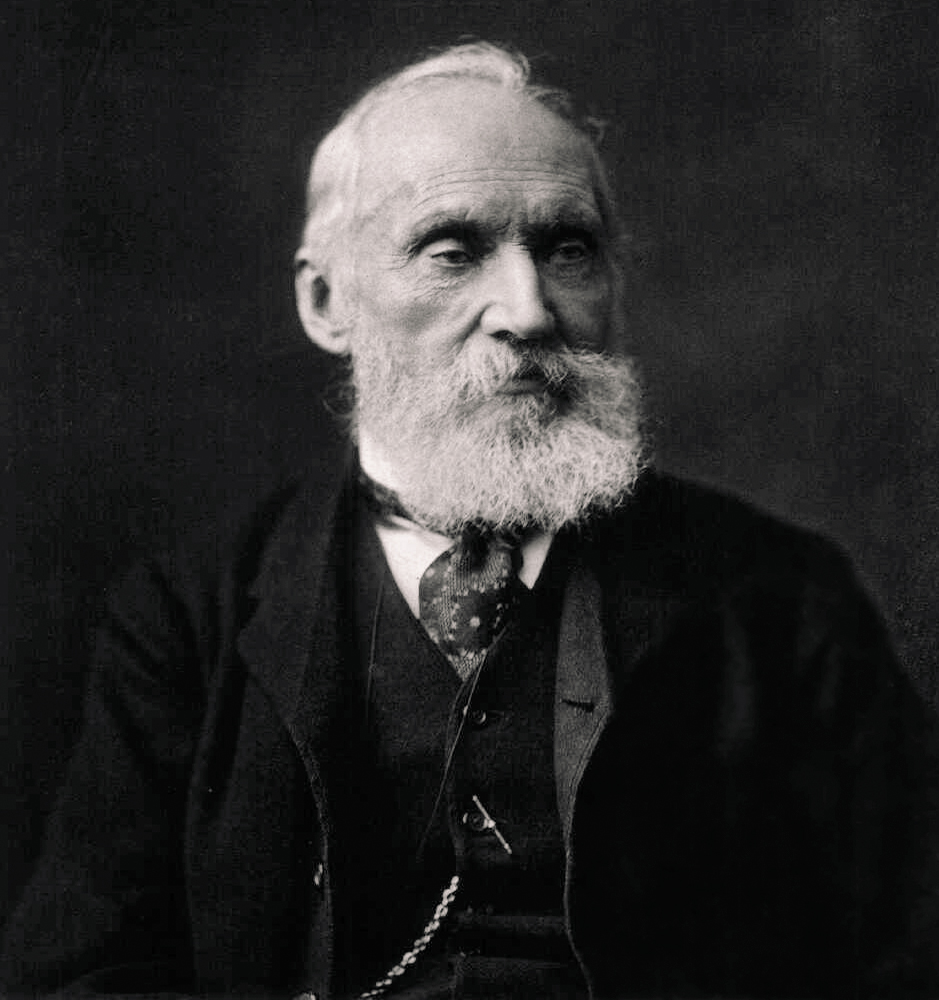

To say that theories contended at the time is an understatement. In the 19th century Lord Kelvin (Fig. 1) lent his formidable intellect to the problem and had come up with the answer: initially, 20 million years, based on an estimated rate of cooling of the earth (before radioactivity was discovered and its heating effect on the core), and he stuck vigorously to his belief in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary while disparaging the geological evidence. In 1906, when radioactive experiments were reported that seemed to disprove his ideas he responded angrily in The Times, which drew a retort: ‘Lord Kelvin’s letter will of course receive respectful attention … but it is also known that his brilliantly original mind has not always submitted patiently to the task of assimilating the work of others by the process of reading’ (The Dating Game – One Man’s Search for the Age of the Earth by Cherry Lewis. 2000. Cambridge University Press, pp. 11-12). Other methods tried to use the salinity of the ocean based on the idea that originally there was no salt in the seas and that it accumulated over time as rivers leached soluble salts from the rocks.

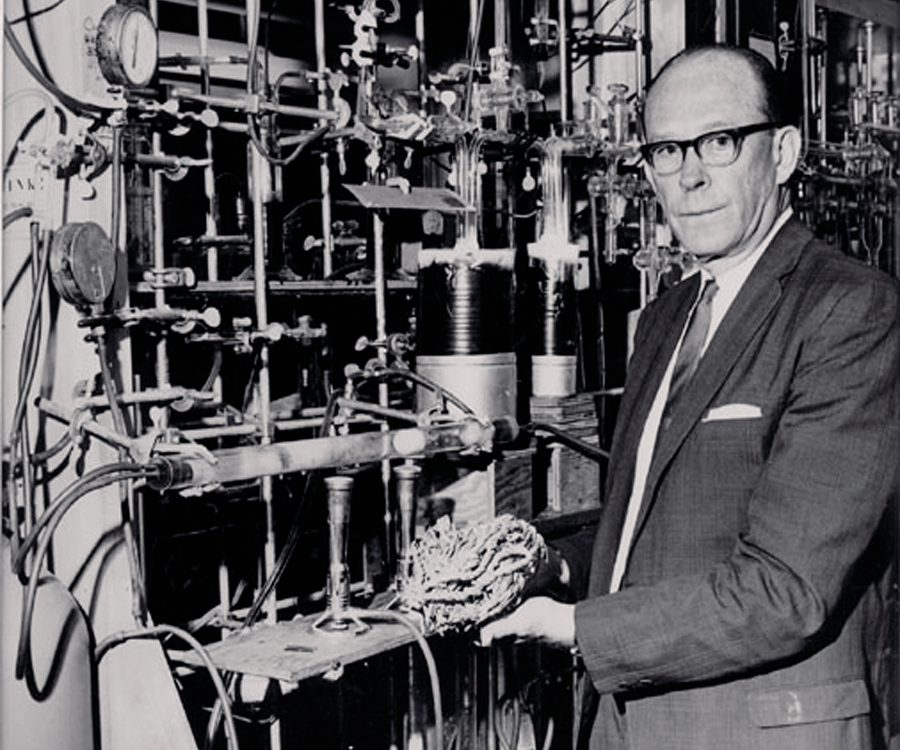

The discoverer of carbon-14, Martin Kamen, died aged 89 in 2002. Carbon-14 is an isotope of the predominant form of non-radioactive carbon (that is carbon-12) formed in the upper atmosphere by cosmic ray bombardment of nitrogen. As such, carbon-14 pervades all living organisms through photosynthesis and the food chain to achieve a steady state condition – so yes, we are all radioactive to some small degree. When organisms die they no longer assimilate carbon-14 and the clock starts to tick. Kamen’s biography Radiant Science, Dark Politics – A Memoir of the Nuclear Age recounts how he lost his academic position at the University of California during the communist witch hunts in the aftermath of World War II, when he was publicly labeled a suspected spy. Charges against him proved groundless and he later received the Enrico Fermi Award for his contributions to physics. The utility of carbon-14 for dating was quick to follow: by 1949 Willard Libby began the development of radiocarbon dating (Fig. 2). That history too is fascinating because the method was validated against organic materials of known date such as ancient Egyptian artefacts and annual tree rings.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com

One would imagine with the exquisite sensitivity and accuracy of the AMS method the problems of dating organic carbon, that is, carbon from formerly living sources, as distinct from ‘dead’ coal or graphite, would be completely settled. This is not the case, however. The problem now is one of contamination by living sources such as pollen spores, fungi, and bacteria all of which skew the results making the source material appear younger than it really is, while ‘dead’ carbon, if present, has the opposite effect. This problem has in turn been addressed by a variety of ingenious sample preparation procedures to purge the contaminants. These include plasma oxidation and a sophisticated statistical method.

https://www.nytimes.com

So what is the age of the earth? It may come as no surprise that it is still not quite settled, but it is agreed to be about four and a half billion years – a significant expansion of the gap between Ussher’s 4004 BCE date and Kelvin’s 20 million. But then, of course, they used very different methods.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation