by Neville Agnew and Tom McClintock

Getty Conservation Institute

Very many people have never visited a rock art site, nor even know what rock art is. For those who can be encouraged to seek out rock art sites, local or even more remote ones that are safe to visit and are open to visitors, a wealth of fascinating experience awaits them. Planning an excursion and waiting for a suitable time will enhance the experience when the opportunity arises. Getting there may require care but for many places in the world it is possible to travel locally in safety with due precautions. And if the pandemic does not abate and it proves unsafe to venture out, then follow the #RockArtNetwork on Facebook or investigate options online for exploring rock art virtually.

The Rock Art Network has crafted a statement: ‘Why Rock Art is Powerful and Relevant Today: Rock art- ancient paintings and engravings on rock surfaces – is a visual record of global human history. It is a shared heritage that links us to powerful ancestral worlds and magnificent landscapes of the past. It tells the story of the birthplaces of art, the dawn of artistic endeavours. It creates connections to significant places and depicts encounters with the surrounding living world. Through its existence nature and culture are connected in the landscape. It resonates with our individual and collective identity while stimulating a vital sense of belonging to a greater past. Rock art illustrates the passage of time over tens of thousands of years of environmental and cultural change. It incarnates the essence of human ingenuity and facilitates contacts today between cultures and aspects of spirituality. Rock art is artistically compelling and full of meaning. This fragile and irreplaceable visual heritage has worldwide significance, contemporary relevance and for many indigenous peoples is still part of their living culture. If we neglect, destroy, or disrespect rock art we devalue our future’.

Is rock art actually relevant right now? The question is sometimes asked in all sincerity. It’s been there often for thousands of years and could wait while the immediate crisis is dealt with. The short answer is, of course, yes. But why is it? On the one hand it is a visual record of our human ancestors and of past cultures, and on the other it is still vital to the well-being of communities that made the art and still continue to do so today. Brady and Taçon, for example, have written that “world rock art is not just a part of archaeology and the distant past but it also has much contemporary importance and remains a part of living culture in many societies”. Far from being irrelevant today in the face of the threats we face, rock art in its setting can act as a powerful stimulus to a sense of well-being while conveying the scale of time, human and geological, to young and old. Its educational value is immense by awakening the imagination and so engendering a love of enquiry that will adhere. Although of the past, we should think of rock art as part of our living and universal heritage. Peter Robinson, editor of the Bradshaw Foundation website, points to the words of writer Robert Macfarlane to express the enormous implications of the current pandemic:

‘The philosopher George Bataille visited the cave at Lascaux in 1955, fifteen years after its discovery, at the point when the nuclear arms race was entering rapid escalation, and atomic testing was being pioneered in underground chambers and desert spaces. A new order of destruction was declaring its possibilities: the annihilation of a species, of a planet. ‘I am simply struck,’ wrote Bataille after surfacing from Lascaux, ‘by the fact that light is being shed on our birth at the very moment when the notion of our death appears to us.’

Art on rocks is literally everywhere in the world, from Norway to New Zealand, from California to China and everywhere in between, and some sites have depictions of great age. What is there to hold our attention at a site, and that of accompanying family, especially children? When visiting a rock art site, we are experiencing a landscape and a natural environment of sky, trees, mountains, desert or tundra, prairie or forest and the chance of seeing the creatures that live in these diverse habitats – we will reconnect with the people who lived there in times before ours. Far from being a subject of little interest rock art offers unique opportunities for enrichment of our knowledge and reflective insights that contrast with our crowded and overly busy and stressful lives – and the physical benefits from getting to the site.

Rock art poses many questions to engage the mind: who made it, why and what does it mean, and inevitably – how old is it? If painted, what are the colours made of? If engraved or pecked, how was that done? What kind of rock is it on and why here but not there? These are questions that can encourage children’s curiosity too, particularly when the questions arise about the people and communities who made the art. Such questions lead to others about peopling the earth and the realization that our way of life is so recent as to be a mere blink in time. We are not so very far away from our ancestors and have become societies of the new technological age, increasingly known as the Anthropocene. So profound is the impact of the pandemic that perhaps only a few people remain anywhere who have not heard of COVID-19. One might seek them in certain Andaman and Nicobar Islands, though that is reliably reported to be inadvisable as they fiercely repulse all outside contact, having been decimated by introduced diseases like influenza and measles in the 19th century – a not uncommon consequence in many places of modern expansion into hitherto isolated areas, which we should also reflect upon in our current situation.

Rock art is as yet a relatively little known and appreciated cultural resource, strangely, because it is both archaeology and art too, though the word ‘art’ is sometimes disputed as an appropriate one for markings, painted or engraved, on natural rock surfaces. Be that as it may, the term ‘rock art’ is here to stay, and the ‘gallery’ is the wide world of nature and environment waiting to be explored and experienced. For those who seek out a site for the first time there is much to be gained as explained in Sharon Sullivan’s article, to be published shortly, ‘How to Visit a Rock Art Site’.

Photograph 1 (Above) A visit to the White Shaman site in the Lower Pecos region of Texas can be arranged through the Witte Museum in San Antonio.

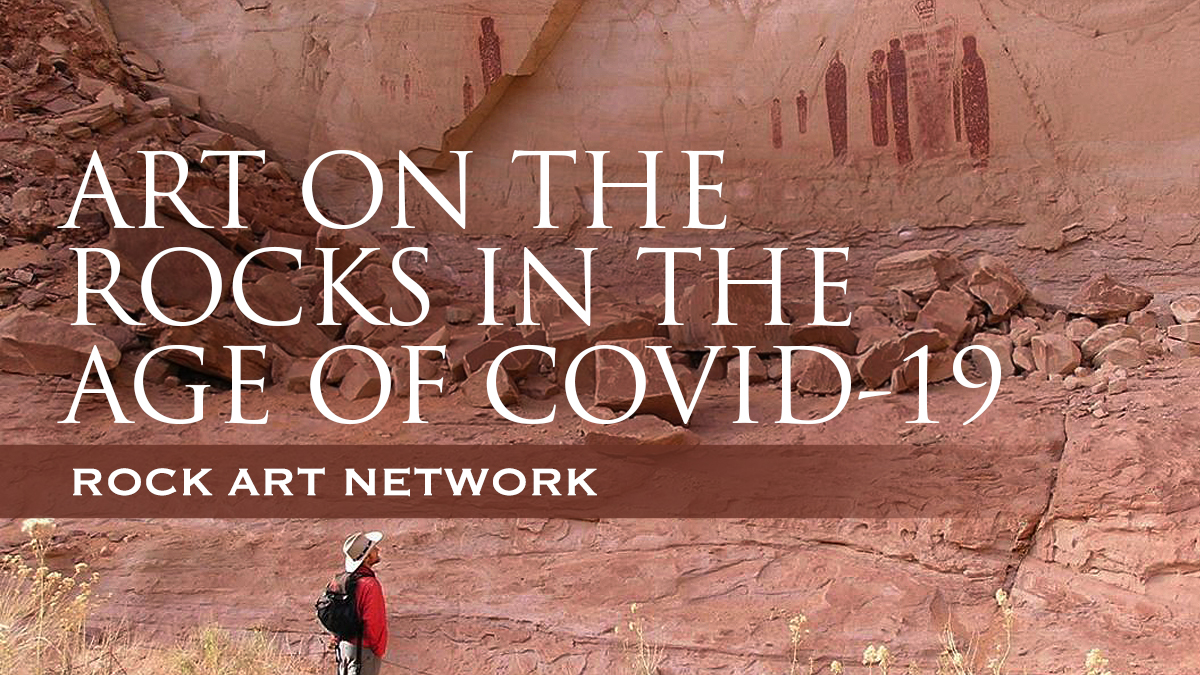

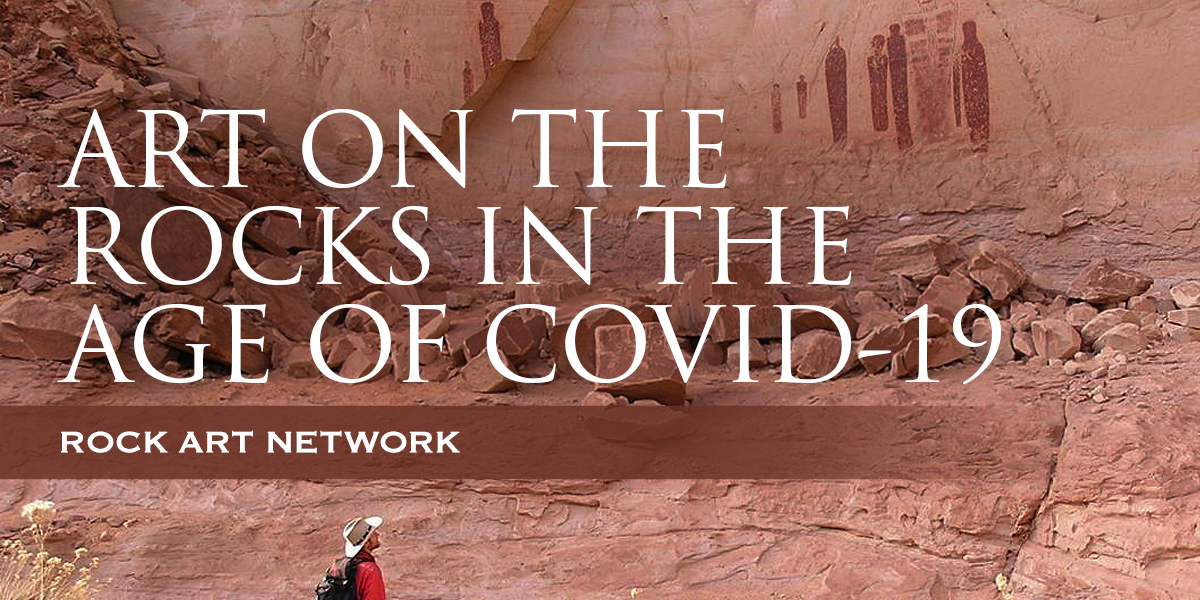

Photograph 2 (Above) The Butler Wash Panel in Utah can be accessed by a public hiking trail.

Photograph 3 (Above) In the age of Covid-19, a hike in the outdoors is a good way to enjoy the company of friends and family while maintaining safe personal distance. All the better if the destination of such a hike is a rock art panel.

Photograph 4 (Above) By definition, rock art sites are situated in the landscape. They are often placed deliberately on unique and compelling geologic features, such as this horseshoe-shaped outcrop of Painted Rock, in California’s Carrizo Plain.

Photograph 5 (Above) Rock art often depicts local wildlife, contemporary or extinct, and is a reflection of what its creators saw in the world around them. Here, an elephant at Twyfelfontien in Namibia can just as easily be seen walking in the landscape as pecked into the rocks.

Photograph 6 (Above) Hiring a local guide can greatly contribute to the experience of visiting rock art sites, such as here in the Drakensburg mountains of South Africa.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation