by Andrew Bock

This article was originally published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 May 2020

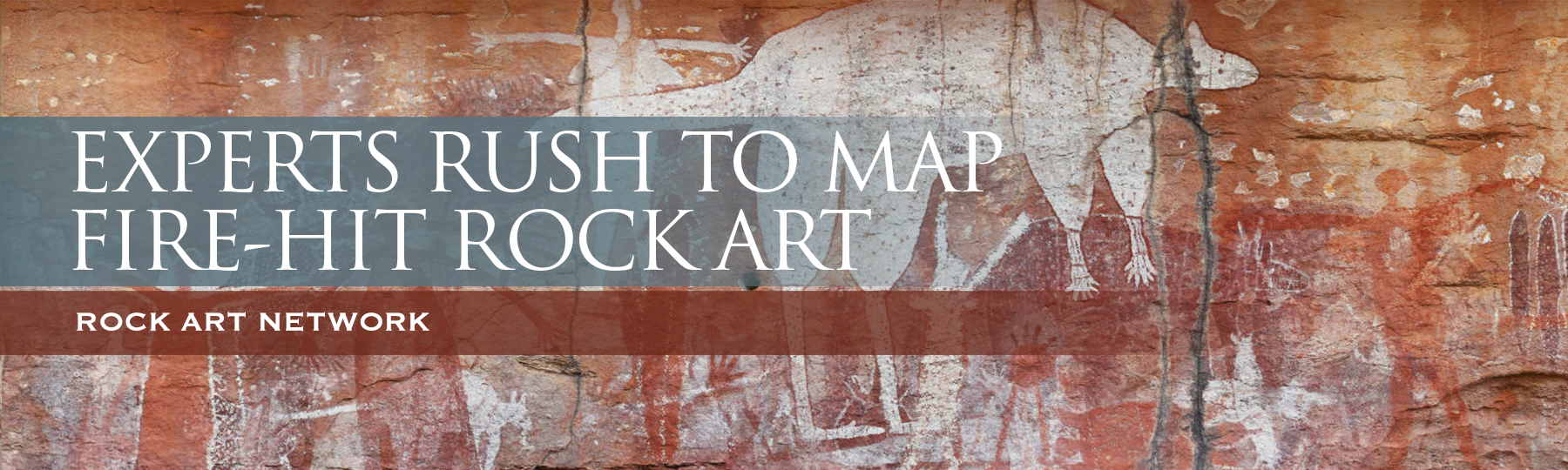

New digital technology could be used to reconstruct 3D images of important Indigenous rock art sites destroyed by bushfires that ripped through eastern Australia last year and early this year.

While coronavirus restrictions have forced surveys to be postponed until September, experts still fear thousands of rock art sites, some dating back 4,000 years, have been destroyed.

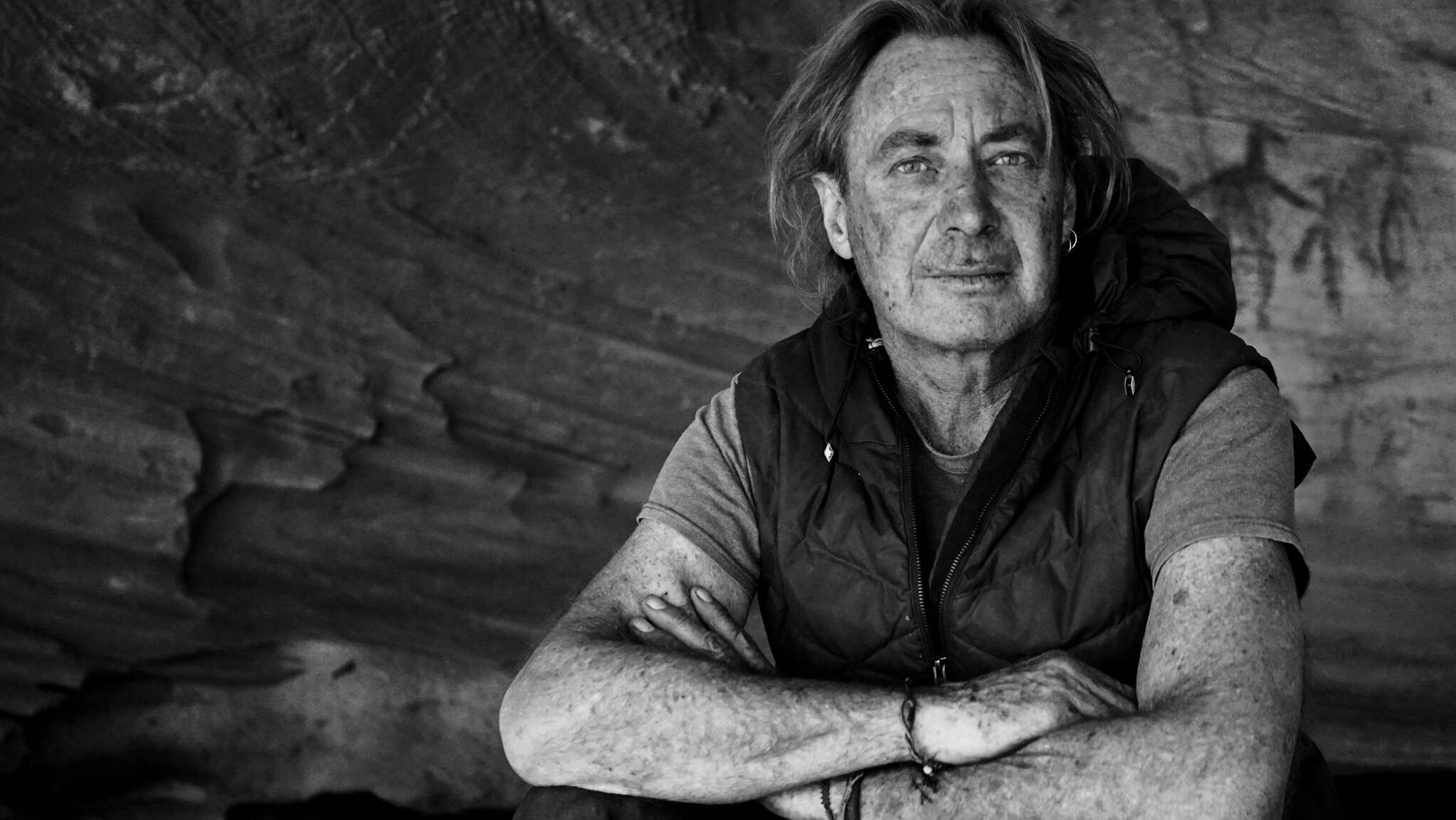

Professor Paul Tacon, head of the Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit (PERAHU) at Griffith University, said some accessible rock art sites, such as Baiame cave near Mount Yengo in the Hunter region, had been visited and found to be undamaged. But he is concerned about important sites such as Gallery Rock and Eagle’s Reach in the Wollemi National Park, 200km north-west of Sydney, which is part of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage area ravaged by fire.

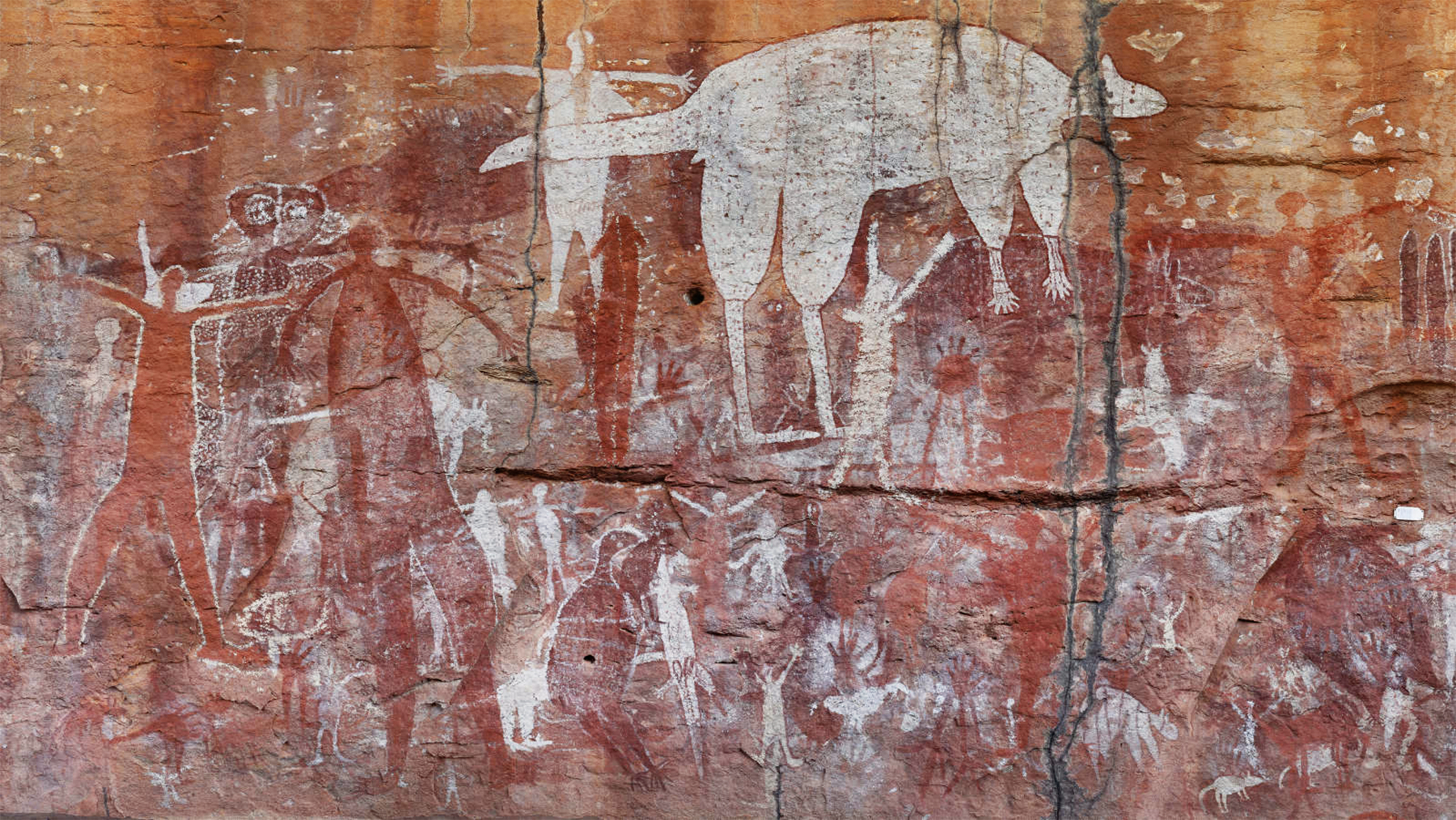

Rediscovered by bushwalkers in 1995, the remote Eagle’s Reach shelter features more than 200 depictions of ancestral beings, totemic animals, animal-human creatures, hand stencils and abstract designs. It is also a key Eagle Ancestor site, ancient initiation place and meeting point for local Indigenous communities.

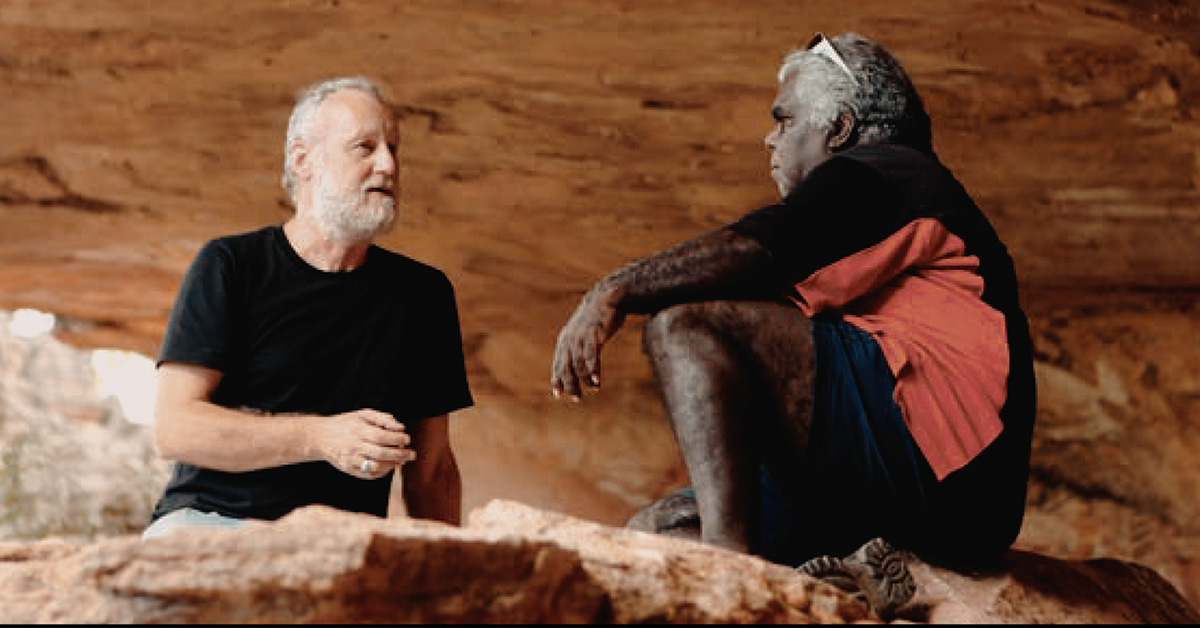

Together with members of local Indigenous communities, Tacon and rock art heritage unit members have surveyed Eagle’s Reach and more than 200 sites in the Wollemi National Park over the past 15 years, taking high-resolution photographs and recordings.

“One of the key activities of PERAHU is using technology to record and analyse rock art in new ways. We've been doing lots of 3D recording, photogrammetry, portable X-ray fluorescence and analysis of pigments and using drone footage to help record sites,” Tacon said.

“If we have the time and money and we find important sites that have been damaged, we can reconstruct them virtually using existing photographs and we can make 3D models of those sites, and with a 3D printer even produce a hard copy version and put that in a cultural centre or museum,” Tacon said.

Dr Andrea Jalandoni, research fellow with PERAHU who specialises in digital techniques for recording rock art, said software advances had improved photogrammetry radically in the past 10 years. Dr Jalandoni also merges photogrammetry with laser scans of sites to create better 3D images. She is also pioneering digital techniques that dramatically reveal rock art barely visible to the human eye.

The same processes could be used for rock art sites damaged by the fires, Tacon said.

Bidjara woman and film and VR producer Ljudan Michaelis-Thorpe is discussing with her community ways to use photogrammetry to create a 3D digital restoration of the Baloon Cave in central Queensland after the rock art was destroyed in a fire in late 2018.

Michaelis-Thorpe said it was important to include and even train community members in photogrammetry and recording so the process was self-determined by traditional custodians. Digital representations “also offer farm owners who have previously kept sites hidden, the opportunity to share the [rock art] while still maintaining autonomy,” she added.

“Baloon Cave is, for the diverse peoples of Carnarvon Ranges, like the holy sites of Jerusalem are for Christians, Muslims and Jews,” she said.

“The songlines and the stories that go through that country still remain but those animals and the law associated with them have taken a hit. This fire culturally is a big wake-up call for everybody," Brennan said.

“It’s not just about the art - it's about looking after the country that the art is in. There’s no separation for Aboriginal people between nature and culture. A lot of those sites are strongly connected to those totems in those particular areas. And the people are going to be hurting at a spiritual level. The recordings, the photographic records we have made, the details, are just so important now.”

Brennan called on the government to fund localised rock art maintenance teams, with Indigenous community members trained by specialists, to better record and conserve rock art. Those teams might then become self-funded by conducting cultural tourism, he added.

“This fire damage could be the order of the next 50 years, and so we could lose a lot of this type of heritage if it's not recorded. We have only recorded less than 20 per cent of the sites in the Wollemi National Park," he said.

“There's not going to be another opportunity like this to survey the Wollemi National Park, because it's never burnt this much or this hard. It's unbelievable how quickly you can walk through the country after a burn. Fire also cleanses the land. There's no doubt we will discover new sites.”

The NPWS spokesperson said a rock-art assessment program would begin when access issues were resolved. NPWS cited seven sites, as yet uninspected, located in the active and burnt areas of national parks. These are the Biamanga, Burrel Bulai, Devils Chimney, Mount Yengo, Saltwater, Sugarloaf (Gwydir) and Waratah Trig Aboriginal places.

→ This article was originally published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 May 2020

→ Rock Art Network Films: Paul Taçon - Griffith University's Laureate

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation