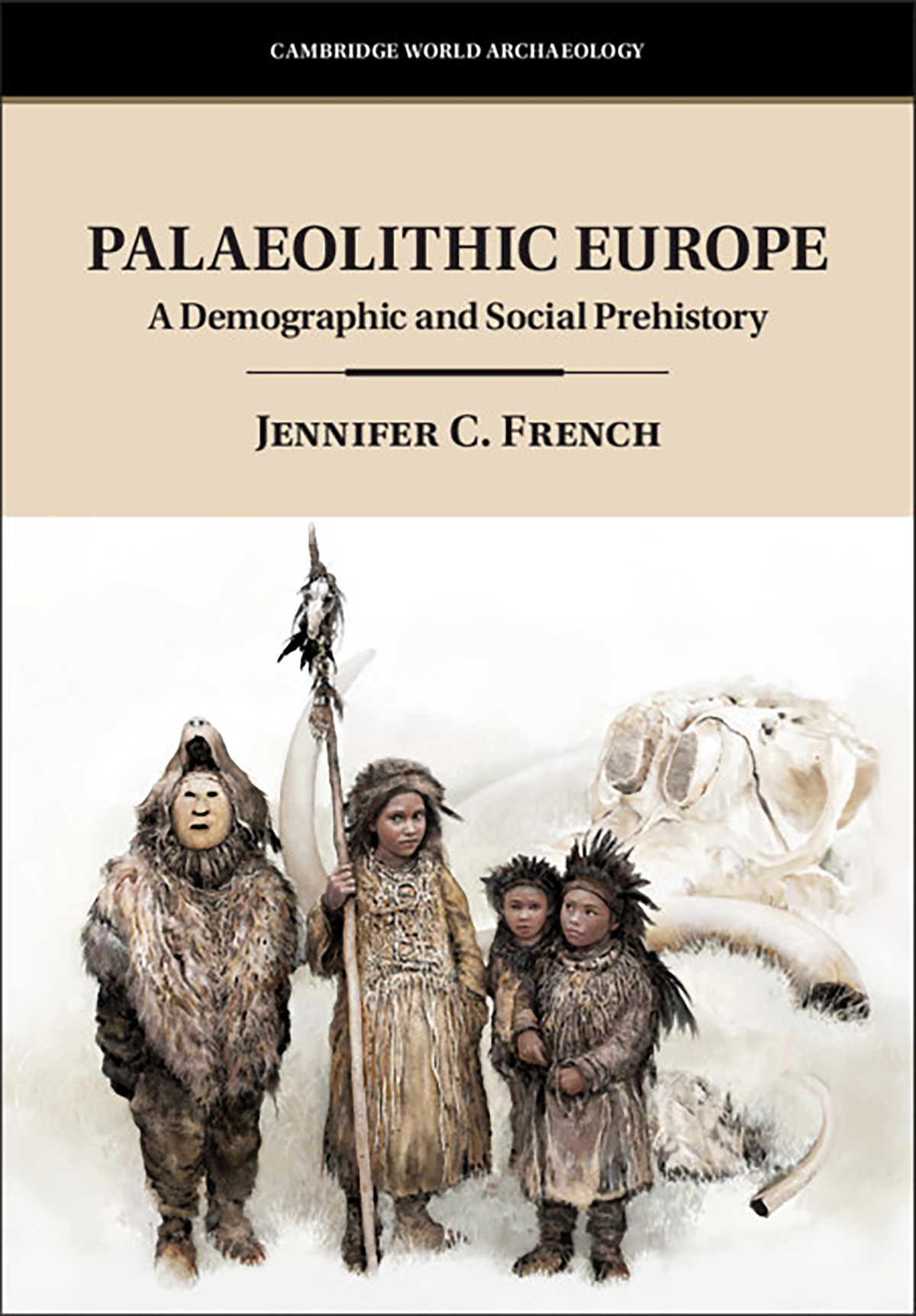

'Palaeolithic Europe: A Demographic and Social Prehistory' by Jennifer C. French

New Publication

This book presents a new synthesis of the archaeological, palaeoanthropological, and palaeogenetic records of the European Palaeolithic, adopting a unique demographic perspective on these first two-million years of European prehistory. Unlike prevailing narratives of demographic stasis, it emphasises the dynamism of Palaeolithic populations of both our evolutionary ancestors and members of our own species across four demographic stages, within a context of substantial Pleistocene climatic changes. Integrating evolutionary theory with a socially oriented approach to the Palaeolithic, this volume bridges biological and cultural factors, with a focus on women and children as the drivers of population change. This volume shows how, within the physiological constraints on fertility and mortality, social relationships provide the key to enduring demographic success. Through its demographic focus, this book combines a ‘big picture’ perspective on human evolution with careful analysis of the day-to-day realities of European Palaeolithic hunter-gatherer communities—their families, their children, and how they lived and died.

About the Author

Jennifer C. French is a Lecturer in Palaeolithic Archaeology at the University of Liverpool. She holds a PhD in Archaeology from the University of Cambridge. Her research on humanity's early demographic history has been funded by the AHRC, the Leverhulme Trust, and the Wenner-Gren Foundation and published in Science,Evolutionary Archaeology, Journal of Archaeological Science, and Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

Product details

Publisher: Cambridge University Press; New edition (9 Dec. 2021)

Language: English

Hardcover: 348 pages

ISBN-10: 1108492061

ISBN-13: 978-1108492065

Dimensions: 18.42 x 2.54 x 26.04 cm

Bradshaw Foundation review

Jennifer C. French's publication 'Palaeolithic Europe: A Demographic and Social Prehistory', published in 2021, is masterful. As Editor of the Bradshaw Foundation, which is primarily concerned with ancient rock art, for years I have been told by rock art researchers that the reason there were so few representations of the human figure in, for example, the Palaeolithic art of the decorated caves of Europe was because humans were a relatively insignificant part of the natural matrix. Meaning, the human population was very very small at this time. Whilst I have mixed feelings about this rock art motif explanation, it certainly triggered the question 'Well, how small?' What was the Palaeolithic population in Europe, and how on Earth could you measure it? Which is how I noticed French's new book.

In the Preface the author explains why this area of research is important, given that there is a 'rather detached attitude to prehistoric populations'. Because after all, we are dealing with 'some of the most meaningful and intimate relationships and events that humans experience'. Or should I say 'hominins' - the publication includes archaic hominins, even though French goes on to suggest that all hominins who lived during the European Palaeolithic were 'humans'. Another salient point that is established early on is that for these human societies, demography is structured by biology but shaped by culture. She justifies the social perspective by stating 'At times my interpretations may stretch the data somewhat, but these 'leaps of faith' are required to write a demographic history that doesn't just populate the Palaeolithic, but also peoples it.' Hear, hear! Getting a demographic grip on some three million years - the Palaeolithic - provides an understanding of 'both humanity's long-term population history and the substantial social and cultural developments that occurred during this period, including the origins of art and symbolism and the colonisation of an increasing array of new environments.'

French sets up her stall straight away. She is working with archaeological, palaeoanthropological and genetic data (and with reference to ethnological data) in order to ask 3 key questions. Firstly, what factors limited population - fertility and mortality - over time and space? Secondly, how do demography, sociocultural change and environmental change relate? And thirdly, what can these demographic patterns really tell us about transitioning Palaeolithic societies?

There is no direct demographic data for non-literate prehistoric populations. So, the author explains the use of demographic uniformitarianism which refers to the assumption that demographic processes are unchanged between the past and the present. Simply put, basic biological processes such as fertility and mortality remain the same. (This uniformitarian approach has been used to some extent with the interpretation of rock art.) French points out that this approach needs careful handling and does not apply to archaic populations.

Given the apparent restraints into this investigation, the author also uses the framework of Human Behavioural Ecology which is based on the underlying principle of optimality in human behaviour. From these primal urges of maximum reproduction and fitness, the framework - admitedly a biological one - allows for hypotheses concerning the demography of Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers. But we humans are not purely biological creatures; French explains that demographic behaviour is also 'cultural' and thus social norms and practices must be factored in.

The book also focusses on the 'demographic core' - women and children. This, thank goodness, takes us well away from the 'Man the Hunter' paradigm For the author, these are the key drivers of population change; female fertility and infant/child mortality. For the former, the 'fertility of hunter-gatherer women is strongly constrained by their energetic condition as part of their overall reproductive physiology.' In other words, energetically stressed women have lower fertility. Well-nourished women were more likely to have a positive energy balance. This caused me to think of the Ice Age figurines - 'be' like this and amazing things will happen. Further support for one theory suggesting the figurines were made by women for women.

I mentioned ethnography earlier. To support the socio-cultural variables in prehistoric demography, French describes the importance of ethnographic research from living or recent-historical subsistence-level societies. You'd think this would be 'a gold mine compared to the database we have for Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers', however it's not. There are too many variables and again the author handles these data with care.

To sum up, French takes great care to explain how she approaches the demography and social prehistory of Palaeolithic Europe, spanning a considerable period of time and over a vast and varied landscape. Once this has been established, the publication flows smoothly into 4 logical and highly readable parts:

VISITATION: THE FIRST EUROPEAN POPULATIONS (c.1.8 MILLION-300,000 YEARS AGO)

RESIDENCY: THE NEANDERTHALS AND THEIR NEIGHBOURS (c.300,000-40,000 YEARS AGO)

EXPANSION: THE ARRIVAL OF HOMO SAPIENS IN EUROPE AND THE EXTINCTION OF THE NEANDERTHALS (c.50,000-35,000 YEARS AGO)

INTENSIFICATION: MID-TO-LATE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC POPULATION DYNAMICS (c.35,000-15,000 YEARS AGO)

All of the above present fascinating material, but my bias left me enjoying the latter two the most; the way French looks into the 'non-lithic component of the archaeological record across the Middle-to-Upper Palaeolithic transition' - now with the benefit of carbon dating - including the increase in portable and parietal art, personal onaments, and long-distance exchange is measured yet engaging. For Neanderthals and Homo sapiens she analyses the transitions and the interactions, and tackles the complex subject of how demography can - and perhaps can not - explain cultural changes. For the Mid-to-Late Upper Palaeolithic she explores the human presence on the landscape and the social lives of individuals and groups. Climate and local environmental conditions were still an issue but populations adapted and thrived, and by this stage these groups of Late Glacial hunter-gatherers were mixing at an interregional level. Just imagine the spread of ideas, among other things.

I used the term 'masterful' to describe 'Palaeolithic Europe' because this publication successfully strikes a balance between hard-hitting science and lucid and mindfull extrapolation, providing a fuller picture of Palaeolithic life and winning a place in every serious library. It is a definitive resource in this field of research, and one that archaeologists, palaeoanthropologists and geneticists can benefit from. I openly admit that a lot of the science was beyond me, and at such times it conjured up phrases that included words like 'bitten off' and 'chew', 'reach' and 'grasp'. But for me it did present a very vivid picture of Palaeolithic life in the land we now call Europe; it put flesh on the bones, artists behind the art, families around the hearth, groups meeting groups. It reinforced the commonality of needs and desires, and joys and sorrows.

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 24 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 27 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 08 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 11 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 02 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 16 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 16 March 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 24 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 27 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 08 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 11 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 02 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 16 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 16 March 2021

Friend of the Foundation