The complex covers roughly 200 hectares, a vast Cretaceous limestone outcrop of the Jandaíra Formation, approximately 90 million years old. It is a karstic landscape, sculpted by erosion and dissolution into a labyrinth of pavements, dolines, sinkholes, and shallow rock shelters. Across this fissured terrain, hundreds of painted and engraved motifs appear, forming one of the most monumental, densest, and continuous bodies of prehistoric imagery in Northeastern Brazil.

Source: Leonardo Troiano

Most of the motifs are abstract par excellence: points, lines, circles, meanders, and geometric configurations, though some rare figurative representations can be discerned, including birds and reptiles. Pigments occur mainly in shades of red, yellow ochre, and black, occasionally overlapping in superimposed layers, creating new hues, such as beautiful oranges. The pictorial stratigraphy implies a long tradition of rock-art-making, likely spanning several millennia and involving successive groups that reused and re-signified the same rock surfaces.

Current estimates place the production of these paintings and petroglyphs roughly between 5000 and 3000 years before present, within the broader context of the Agreste rock art tradition. Archaeological evidence from the surface, or rather, the conspicuous rarity of material culture such as ceramic fragments and lithic tools, suggests that the Lajedo was not a domestic space but rather a ceremonial and collective locus, repeatedly visited by human groups for ritual activities, and perhaps, the occasional hunting of big Pleistocene game.

The distribution of motifs in difficult or concealed locations, beneath overhangs, along ravine walls, and in narrow corridors, indicates intentional control of visibility. The act of seeing and moving through the terrain was likely integral to the place's symbolic experience. The spatial and physical engagement required by the site is remarkable. To perceive many of the paintings, one must stoop, climb, or lie on the rock; vision and movement become interdependent. This corporeal interaction, though not romanticized here, is archaeologically significant: it implies embodied gestures in image production and reception, linking the present observer with the physicality of the prehistoric painters.

The Lajedo’s sheer concentration distinguishes it from other Brazilian rock art ensembles, such as Serra da Capivara, where imagery occurs in discrete and isolated shelters scattered across thousands of hectares. In contrast, the Lajedo forms a continuous symbolic landscape, a unified topography of artistic expression in which geology, rock art, and Indigenous memory are effectively one.

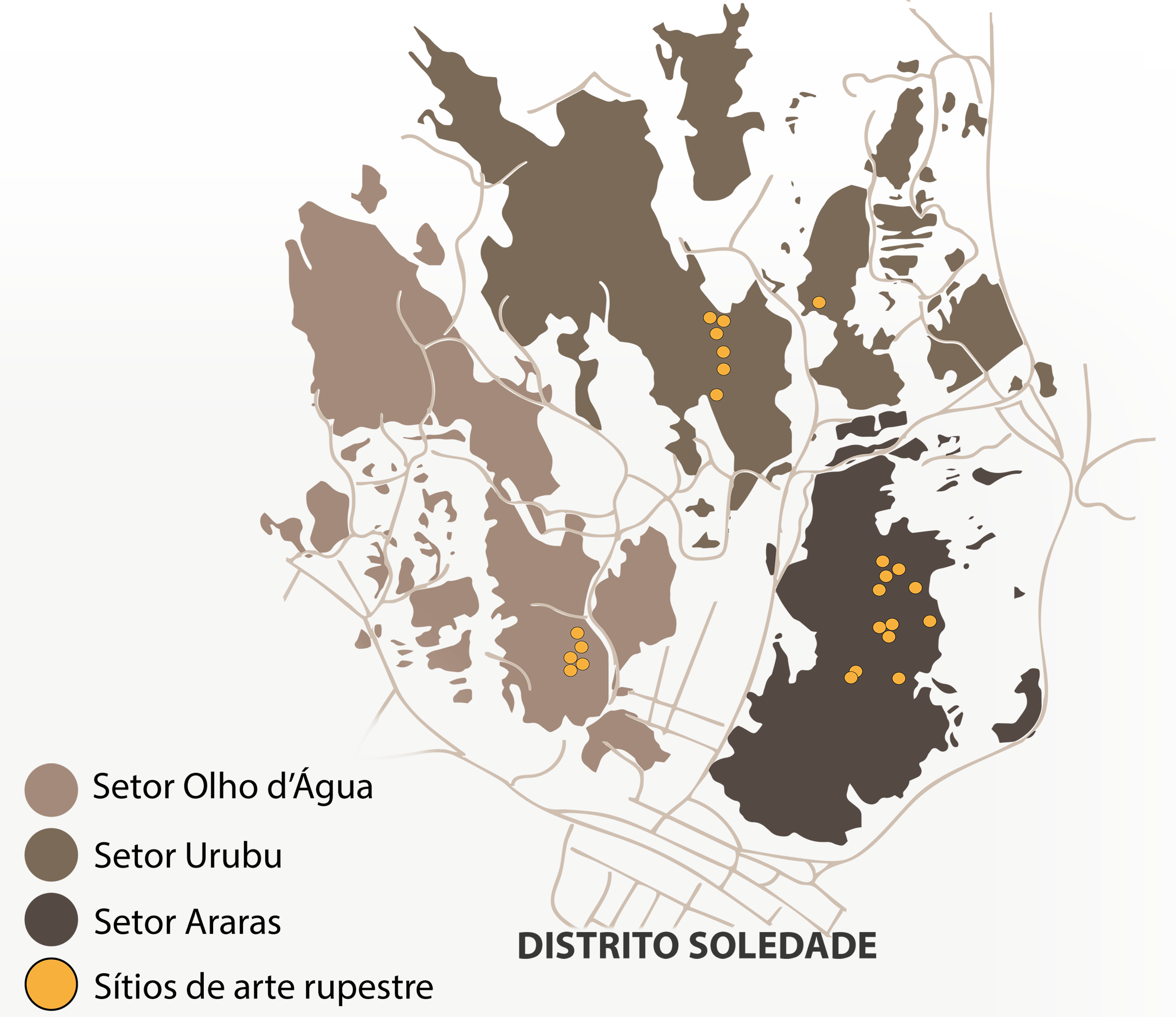

The preservation status of the pigments is truly exceptional, and many motifs look as vivid as if they were painted yesterday. Many figures retain chromatic intensity, defying the climatic harshness of the semi-arid Caatinga. Such durability results from both the material mastery of ancient artists and the protective qualities of karstic microenvironments. A total of twenty-one large pictorial panels and twenty-two engraved panels have been identified so far. Their number is further increased by the countless standalone motifs scattered across the karst, often appearing in the most unexpected places. It would be impossible to discuss them all here, so we will focus on the main sites within the mega-site complex, divided into three sectors clearly defined by the underlying geology.

Dodora’s Ravine extends for nearly a hundred meters in a straight northwest–southeast line and contains at least four decorated shelters. Each hosts panels of red-ochre pictographs that together form one of the most cohesive and intriguing visual sequences in the Lajedo. The central and first panel, known as Dodora’s Panel, displays a disciplined geometry with grids, concentric circles, subdivided squares, and interlocking semicircles arranged with evident intentionality along the complex geometry of the limestone surface. The motifs respond to the rock’s natural texture, using cavities and ridges as compositional anchors. Although separated by tens of meters, the shelters read as parts of a single system, unified by style, color, and abstraction, as if pages from a continuous visual text. The extraordinary preservation of the pigments and the absence of figurative motifs suggest a sophisticated symbolic grammar, shared and reiterated by successive groups that reoccupied the same ravine.

Araras’ Ravine, which means Macaws, contains the most extensive and complex repertoire of paintings in the Lajedo de Soledade. The site’s most iconic motif, the red macaw, became the emblem of the Lajedo itself. Surrounding these stylized birds are hand stencils, zigzags, triangles, and linear motifs, creating a dense palimpsest of superimposed forms.

The presence of the lizard and frog figures adds a rare figurative layer within an otherwise visual field where abstraction is sovereign. The varied orientation of the images, with no central axis or focal point, suggests successive episodes rather than a single composition or any form of self-evident “reading” or “narrative” sense. Overlapping layers reveal distinct chromatic phases and an ongoing dialogue with the rock surface across time between cultures. The observer must crouch or even lie down to view specific motifs, an embodied form of vision emblematic of how movement and perception were-and still are-integral to the site’s experience.

The Urubu Ravine, meaning “Vulture”, gets its name from these birds’ preference for nesting there. It also differs markedly from the other decorated sectors. Tucked between two limestone shelves, the Urubu main panel is set under a low ceiling that forces observers to lie on their backs to see it. Its chromatic palette is exceptional: black and yellow dominate, with only a few later red handprints overlaying the earlier designs. Rectangular lattices, parallel lines, and branching motifs are executed with fine detail, using a mineral-based pigment binder containing iron oxides and carbon. Despite its fragility, the panel retains much of its original detail. At its southern end, a cluster of tiny handprints, likely made by children, adds a profoundly human dimension to the site, evoking a sense of intimacy and, perhaps, play.

Named after Indigenous leader Lúcia Paiacu Tabajara, following the local tradition of honoring those who fought for the Lajedo’s preservation, this panel was identified by Manoel Gustavo Lima and Leonardo Troiano during a reconnaissance mission for the National Heritage Institute in 2024. The panel occupies a low shelter, about eighty-five centimeters high and several dozen meters deep, located in a small ravine of the Urubu sector that narrowly escaped destruction. Barely ten meters away, another decorated panel—richly painted and engraved—was criminally destroyed with dynamite to facilitate limestone extraction, not an exception, but the rule at the Lajedo.

Lúcia’s ceiling, which stretches for more than seven meters, is covered by meanders, interlaced lines, and layered pigments in purple-red, yellow, black, and orange. At its center, a vaguely anthropomorphic figure in motion hints at experimentation and a break from the more rigid geometries found elsewhere in the Lajedo. The overlapping pigments produce a distinctive, beautiful orange hue, likely the result of both superposition and long-term chemical interactions. To see the panel, you have to stoop or crawl, a posture that makes you aware of your own body and mirrors the effort of the artist who once painted it.

Located between Dodora and Araras, Peninha’s is more a canyon than a ravine, and by far the most inaccessible of all Lajedo panels. Embedded twelve meters high in the wall of a deep limestone gorge, it can only be reached by climbing, each step demanding a willingness to court real danger. Peninha’s panel had never been mentioned in the literature, nor had it ever been documented, so when I glimpsed it from the opposite side of the gorge, I had to try to see it. I climbed to the shelter in a careless moment of euphoria. As many colleagues will know, the prospect of encountering new rock art can release enough adrenaline to grant brief surges of impossible stamina. Too perilous to reach a second time, I later decided it was best to have the panel’s 3D model produced entirely by drone. I hope that someday a faithful, full-scale replica of this fundamentally inaccessible panel can be created and displayed at the local museum, since any structure built to make it accessible would compromise the integrity of the landscape-and cost far too much.

Within this vertiginous small shelter, red geometric figures appear, formally akin to Dodora’s visual repertoire: lines, rectangles, and, above all, a striking spiral locals call the “DNA.” Their placement, high and concealed, suggests a symbolic engagement with danger, effort, and elevation, perhaps pointing to rites of initiation, displays of physical prowess, or some form of ascent. The interaction between form and substrate is again deliberate as the motifs occupy natural recesses, making the rock itself part of the composition.

The Olho d’Água is a stunning doline—an underground chamber now exposed after its ceiling caved in due to erosion—that today forms a kind of seasonal lagoon. Its holding capacity is such that this natural reservoir often becomes the last source of water several months into the brutal dry season. During the Early Holocene, it was undoubtedly a lifesaver for megafauna in summer, as evidenced by the surrounding ravines, which are packed with fossils of animals that became trapped. Today, however, it serves no such purpose, as the water is contaminated by lime dust. During extreme droughts, when the water recedes, it reveals an extensive ring of petroglyphs carved into the limestone rim.

The Olho d’Água petroglyphs form one of the most intriguing ensembles in the Lajedo, characterized by deep linear grooves radiating outward from central concavities or cupules. Around the larger cupules, smaller ones appear like satellites, connected by channels and incised lines that together create a complex, almost map-like composition. Only one faint painting was identified, and even this was discernible only after applying DStretch enhancement to a photograph taken at the site. It is likely that other painted motifs once existed. Still, the site’s cyclical flooding events would have destroyed most pigment layers, leaving only the more resilient petroglyphs that now dominate its surface.

Eighteenth-century records describe the doline as “packed and clogged” with ceramic fragments and note that, when settlers removed them, the cavity flooded. I can think of no plausible reason why Indigenous peoples would have intentionally blocked the major natural water source of a region so arid that a puddle can be the difference between life and death. But if, as described by Menezes in 1799, these sherds were Indigenous, why were there so many of them, enough to clog a lagoon? Could the site have been a place of ceremonial consumption, and perhaps ritualized breakage and the discarding of objects—a practice by no means unheard of in the archaeological record (think of the case of Minoan conical cups or the Greek Island of Keros and its broken Cycladic figurines)? A more likely explanation may be a natural clog formed by the accumulation of sediment and ceramic fragments that gradually drained into the doline’s spring. Another possibility is that the blockage resulted from colonial warfare, in which settlers deliberately sought to deprive Indigenous groups of access to water. Oral traditions indeed remember the Lajedo as a place of refuge during the European incursions that struck the coastline and forced Native Brazilians inland. Cutting off vital water sources would have been a devastating tactic, one consistent with the broader patterns of violence that characterize the colonial period.

However, no systematic excavation of the doline has ever been carried out to clarify this question. If it once contained said artifacts, it now seems unlikely that they could be recovered after two centuries of anthropogenic disturbance.

In the northeastern sector lies, in my view, one of the most compelling sites in all of Brazil: the Capelinha Tunnel. It is without doubt one of the most evocative and surprising contexts in the entire Lajedo. This narrow karstic cavity, accessible only by descending and crouching—and occasionally flooded during the rainy season—opens into a small, straight chamber whose ceiling bears twenty-five red pictographs. Thus, its name, “little chapel”. The painted motifs include zigzags, lozenges, rectangles, and aligned points. They are also somewhat alphabetic in design, although clearly they are not letters, and this is just a formal coincidence. Though modest in scale, the composition is remarkably well preserved, aside from a bit of mold along its edges, and carefully balanced. The act of descending, squeezing, and bowing is part of the experience itself. It is a space for contemplation and reverence.

The emotion one feels when visiting this non-public site also stems from its setting. It lies within a section of the Lajedo that has been obliterated by savage mining, which has stripped away the karst's characteristic contours. The entrance hole is invisible until one stands directly over it. I have shown this place to a few friends. After a twenty-minute walk over the sharp limestone surface, we reach the opening. Their first reaction is always disbelief: “Do you expect me to go in there?” Then comes acceptance, followed by a careful but easy descent-about two meters-and, without exception, so far, a resonant wow. Sometimes several.

Around the karst rise, towering limestone kilns-many old enough to qualify as historical archaeological sites under Brazilian law-stand as squat, smoking sentinels that devour the very ravines whose beauty defines this landscape. How much invaluable rock art was turned to dust in these hellish kilns? In the pursuit of quick profit, miners burn the geological body that cradles an irreplaceable archive of human history. Their pale exhaust settles as a fine, corrosive white dust that coats and poisons everything: the ground, the shrubs, the painted panels, and the water. The water here contains so much calcium carbonate that it quickly burns out the circuits of electric showers-the standard type used in Brazil-making hot baths a rare luxury in the region.

As in the case of the Ingá Rock, institutional neglect in these remote regions has allowed the mining coronéis to reign unchecked, turning the archaeological landscape into a pollution factory and monument to the State’s utter ethical failure. Limestone is common, but the imagery carved and painted upon this outcrop exists nowhere else, not even at other sites of the Agreste tradition. The archaeologist Gabriela Martín recognized its uniqueness, defining it as a distinct sub-style within the tradition: the Apodi substyle.

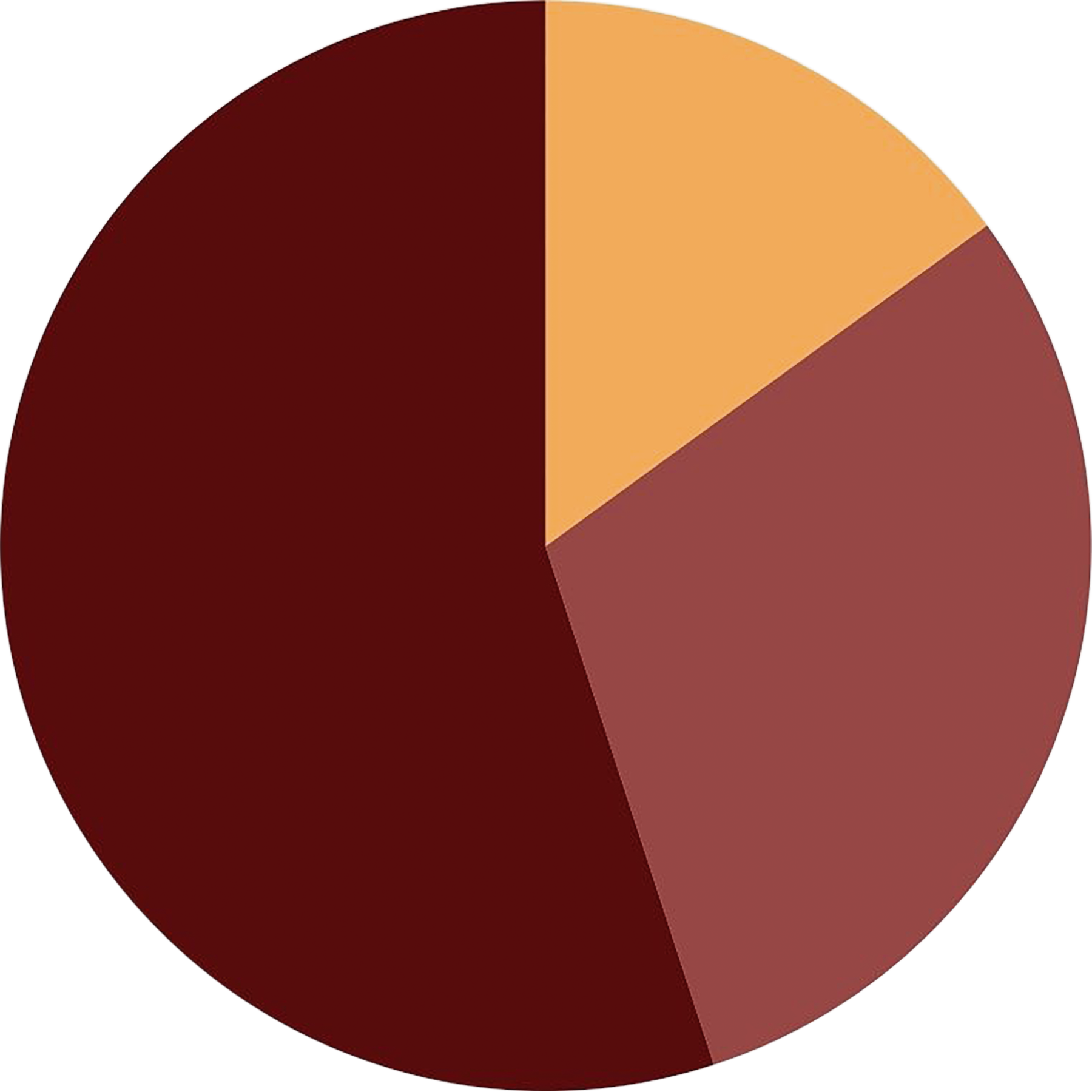

After more than two centuries of extraction, not a single square meter of the lajedo remains virgin. If not broken and mined, the terrain is blanketed in rubble, as the limestone was also quarried for pavement. The areas that appear less damaged are those where human intervention is old enough to have acquired a natural patina. My analysis shows that only about 15% of the karst surface retains more than 75% of its original geological integrity. Once again, no portion of the surface remains fully intact. Unsurprisingly, every known rock-art panel lies within this surviving fraction. Roughly 55% of the Lajedo de Soledade has been erased from Earth’s face entirely. The remaining 30% of the area falls within the moderately to severely degraded range. Only in imagination can we glimpse what the Lajedo once was, in immemorial time, an immense, luminous open-air nexus of culture, ritual, life, and image.

Moderately to Severly Degraded 30%

Preserved 15%

In December 2024, perturbed by this ongoing crime against humanity, I brought the matter to the attention of Rio Grande do Norte’s Governor. In a meeting with her cabinet, she endorsed stronger protective measures for the site. The Governor proposed assisting mining companies in relocating to areas of the Chapada do Apodi where archaeological heritage isn’t present (a rather optimistic premise).

Mining remains the region’s main economic activity, although it doesn’t take much brainpower to see that sustainable archaeological tourism could generate far greater and longer-lasting benefits. But Brazil’s economic elites aren’t exactly renowned for their brilliance. The logic has always been simple: to profit as much as possible by the easiest and cheapest means. These are, inevitably, the most socially pervasive and environmentally destructive means. And precisely because of their destructive nature, such enterprises soon exhaust the natural resources on which they depend. By then, however, the same few family dynasties will have amassed enough wealth to migrate to yet another sordid enterprise. In a country as rich in archaeological sites as Brazil, ancient human heritage will always be caught in the crossfire between public interest and the private ambitions of a few individuals powerful enough to get away with its murder.

A month after we met with the Governor, in January 2025, the State Law No. 12.031/2025 of Rio Grande do Norte officially declared the Lajedo de Soledade Archaeological Site a Cultural Heritage of the State. This redundant measure, as all Brazilian archaeological sites are already listed as National Heritage and protected under Federal Law since 1961, still signifies something. It is, at least, a symbolic gesture and official recognition by the State. As we proposed, the site, though damaged, still possesses, shockingly and against all odds, enough archaeological record to meet UNESCO’s criteria of authenticity and integrity required for recognition as a World Heritage Site (WHS). The Governor welcomed the possibility, which in turn generated numerous headlines, somewhat misleading, suggesting that the site was already on its way to becoming a WHS. This subsequent significant media attention seems to have discouraged locals and mining companies from so shamelessly destroying rock art for mere cents.

A pervasive notion persists that the Lajedo is limited to the Araras sector and that mining will occur “far from visitors’ view,” in the Olho d’Água and Urubu sectors. This intentionally misleading idea creates the impression that the Lajedo’s rock art is confined to the Dodora and Araras ravines, which is far from true. Since these are the only two areas currently visited by tourists, the deception goes largely unquestioned. Meanwhile, mining continues, stealthily eating into the Lajedo, working its way in from the edges and threatening the Olho d’Água petroglyphs, Capelinha, and Urubu panels.

While the Dodora and Araras rock art sites are now too well known to be mined without legal consequences, the surrounding terrain continues to be plundered, steadily losing the geological forms that give it its extraordinary, moon-like character and that likely drew prehistoric populations to the site in the first place. The large mining companies bear much of the blame, though not all of it. Even after forty years of heritage education efforts by a handful of dedicated individuals, including geologist and conservationist Eduardo Bagnoli, many residents still maintain small backyard kilns. Faced with this grim reality and such egregious disregard for our collective heritage, the only viable path forward seems to be more vigorous law enforcement, a genuine transformation of local political culture, and the broad public promotion of the site.

The story of conservation at Lajedo de Soledade begins not with archaeologists, institutions, or decrees, but with one brave woman: Maria Auxiliadora da Silva Maia, known simply as Dodora. In 1978, when Brazil was still under military rule, she began a lonely fight to save the decorated ravines. A schoolteacher and the first woman to become a lawyer in Rio Grande do Norte state, Dodora spent her salary to produce pamphlets, postcards, and local heritage education campaigns that no one else would fund. Villagers mocked her efforts: “Dodora wants to take away people’s livelihood. Who protects stones?” But to her, in her own words, the rock itself was alive. She sold her car to print thirty thousand postcards of the paintings she wanted the world to see. For twelve years, she was the site’s only guardian, confronting miners, priests, and politicians alike. She faced racial slurs and misogyny. One local mining mogul even threatened her, “Shut up, or we’ll burn you alive inside a kiln.” But, she never quit: “You don’t destroy what you didn’t create,” she said. “You build what is missing. And what is missing is environmental consciousness.”

By the early 1990s, the devastation had grown exponentially. In February 1991, a group of environmentalists from Natal, led by geologist Eduardo Bagnoli, joined Dodora in what they called a rescue mission. They named the beautiful geometric panel Dodora’s panel. They lectured to the small community of Soledade, explaining that the limestone beneath their feet was not merely a resource. Nearly three hundred residents came. Many wept, some complained, and a few volunteered. In the days that followed, together they mapped a few critical areas to be preserved, cleared trails, and trained local children to act as junior guides. The Friends of Lajedo de Soledade Foundation (FALS) was born. Supported by Petrobras, FALS built fences around the Araras sector, installed signage, and, in 1993, inaugurated a modest museum to house archaeological artifacts and a wealth of Pleistocene fossils, of which the Lajedo is immensely rich. Under Dodora’s presidency of FALS, more than 300.000 visitors eventually came to see the Lajedo over the years.

Decades later, another woman took up the torch in a different key. Lúcia Paiacu Tabajara, a leader of the Tapuia-Paiacu people of Apodi, turned her ancestral grief into action. Her struggle is not only ecological but historical, a fight against the long and tragic erasure of Indigenous memory in Rio Grande do Norte. “It feels as if my ancestors shout through my blood,” she says. “I miss a forest I never lived in.” Correctly so, as the Holocene Lajedo de Soledade was a much different place, a heavily forested environment that supported megafauna such as South American elephants, giant ground sloths, giant armadillos, sabertooth tigers, toxodons, jaguars, and many more.

In 2023, Lúcia founded the Museu Indígena Luíza Cantofa (MILC) on the shores of Apodi Lake, in partnership with the State University of Rio Grande do Norte (UERN). It is the state’s only Indigenous museum, a house of memory and remembrance that shelters the stone tools and ceramic fragments of the ancient Tapuia Paiacu, including grinding stones, pestles, hammerstones, projectile points, vessels, and other objects that once formed part of Native daily life and ritual. In 2024, the museum received the Darcy Ribeiro Award from Brazil's National Museums Institute, acknowledging its pioneering work in social museology and heritage education. For Lúcia, however, the prize matters less than the pulse that drives her. “Against facts, there are no arguments,” she says. “We were here, and we are still here.”

“It was here, in these caves, ravines, and canyons, that many of our ancestors took refuge as the invaders advanced. Because of their resistance, we, the descendants of the Tapuia Paiacu, continue to inhabit the Apodi Plateau, living alongside the sister species that also find shelter here, beneath the sacred mantle of our biome, the Caatinga, or Ketsékrá in our Brobó language. What scientists call archaeological sites are, to us, living markers of ancestral presence, far more than objects of study or scientific curiosity. They are sacred spaces. For this reason, we demand their preservation, protection, and care. In the face of the ongoing threats brought by economic elites and their extractive ventures, the defense of our heritage is not optional. It is essential to our survival. We stand firm in protecting our rights and our culture, and in affirming the depth of our history. We will march forward until our lands are demarcated, united in the struggle to preserve our sacred spaces-such as the Archaeological Site of Lajedo de Soledade-so that our way of life, our memory, and our history are respected. We call upon all to join this struggle. May this mark the beginning of the true protection of our sacred territory, Twran Limolaigo.” “The Sacred Territory of the Tapuia Paiacu People of Apodi”, by Lúcia Paiacu Tabajara, Chief. November 27, 2024.

While small men-many of them now long dead, with village streets named after them-fade into oblivion, Lúcia at sixty and Dodora at seventy-one remain firm, and with a much more illustrious legacy than street names. A new generation of Lajedo guardians is already here (such as Lúcia’s grandchildren and others).

Dodora’s story, in particular, moves me deeply. As I am sure many colleagues will relate, the adversities and immense forces arrayed against the ancient record we swore to study and protect can often deplete us of energy and hope. Yet citizens like Dodora remind us why we go on. She reminds me of Tennyson’s “Ulysses”. Like the old sailor, she holds on. Though greed has pulverized much of Lajedo’s landscape and rock art, its wealth was such that what remains is still immense—and worth fighting for. “Though much is taken, much abides.”

Now, though not as strong as in her youth, with limited mobility after years of struggle, she still raises her voice in defense of the painted stones of the Lajedo at every opportunity, even if seated in a rocking chair under a well-earned patch of shade on her doorstep. “That which we are, we are; One equal temper of heroic hearts; Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will/ To strive, to seek, to fi nd, and not to yield.”

- Albuquerque, P. T. S. and L. M. S. Pacheco. 2000. O lajedo do Soledade: um estudo interpretativo. In M. C. Tenório (org.), Pré-História da terra Brasilis, pp. 115–133. Editora UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro.

- Bagnoli, E. 1994. O Lajedo de Soledade, Apodi (RN): um exemplo de preservação do patrimônio cultural brasileiro. Revista de Arqueologia 8(1): 239–253.

- Dos Santos Júnior, V. 2013. As gravuras rupestres da região oeste do Rio Grande do Norte. Revista Contexto 4(1–2): 81–92.

- Dos Santos Júnior, V. 2022. A simbologia rupestre do Rio Grande do Norte. Edição do Autor, UERN.

- Lage, M. C. S. M. 2018. Relatório do diagnóstico do estado de conservação do sítio arqueológico Lajedo de Soledade – Apodi - RN: Fichas de avaliação e monitoramento arqueológicos com registro fotográfico (Activity report). W. Lage Arqueologia. Processo IPHAN SEI n. 01421.000148/2018-93.

- Martin, G. 2013. Pré-história do Nordeste do Brasil. Editora Universitária UFPE.

- Martins, G. P. O. 2024. Lajedo de Soledade (Apodi, Rio Grande do Norte): fossildiagênese de vertebrados quaternários, sedimentologia e estratigrafi a. Tese (Doutorado em Geociências) – Faculdade de Geologia, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro.

- Porpino, K. O., V. dos Santos Júnior and M. F. C. F. dos Santos. 2009. Lajedo de Soledade, Apodi, RN. Ocorrência peculiar de megafauna fóssil quaternária no Nordeste do Brasil. SIGEP 127.

- Superintendência do IPHAN no Rio Grande do Norte. 2025. Enclave arqueológico Lajedo Soledade - EALS: identifi cação, georreferenciamento, caracterização e contextualização. Relatório final. Plano de fiscalização 2024 – Reconhecimento internacional de bens arqueológicos – CAGED/CNA (Processo SEI n. 01450.001560/2025-11).

- Troiano, L. P., & de Lima, M. G. S. M. (Orgs.). (2025). Lajedo de Soledade: A preservação do patrimônio arqueológico indígena no Nordeste brasileiro. Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (IPHAN). ISBN 978-85-7334-473-8.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ Brazil Rock Art Archive

→ The Lajedo de Soledade

→ The Rock Art of Pedra Grande

→ the Rock Art of Serrote do Letreiro

→ The Ingá Rock

→ The Peruaçu National Park

→ The Poty River Canyon Petroglyphs

→ Rock Art of Serra da Capivara

→ Rock Art of Pedra Furada

→ The Rock Art of Santa Catarina

→ South America Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network