The Pedra Grande site (its name meaning simply "big rock") is a monumental outcrop of Botucatu sandstone, more than 80 meters long, that rises abruptly from the surrounding landscape in the interior of São Pedro do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul. It emerges amidst a patchwork of plains, low hills, and gently rolling divides that shape the Toropi–Ibicuí sub-basin. The nearby Toropi River, whose Tupi-Guarani name means “armadillo’s path,” winds across this terrain in a series of sinuous bends. Pedra Grande lies within the Atlantic Forest, the once-vast coastal rainforest that suffered the harshest blows of colonial timber extraction, especially of pau-brasil. This redwood ultimately gave the country its name.

As a landscape feature, Pedra Grande is impossible to ignore. It is a landmark and ecological refuge in equal measure. For thousands of years, the shelter beneath this monolith served as a waypoint in the landscape, a place to stop, watch, and occasionally carve. Although northeastern Brazil, with sites such as Serra da Capivara, dominates the global image of Brazilian rock art, Rio Grande do Sul actually holds the country’s highest number of archaeological sites, and Pedra Grande is the largest rock-art panel in the entire southern region. Its sandstone surface seems made for inscription, with broad planes and natural ledges that catch morning light and lend themselves beautifully to engraving. Long before maps or writing, the silhouette of Pedra Grande signaled a place where people paused, camped, and carved their presence into stone.

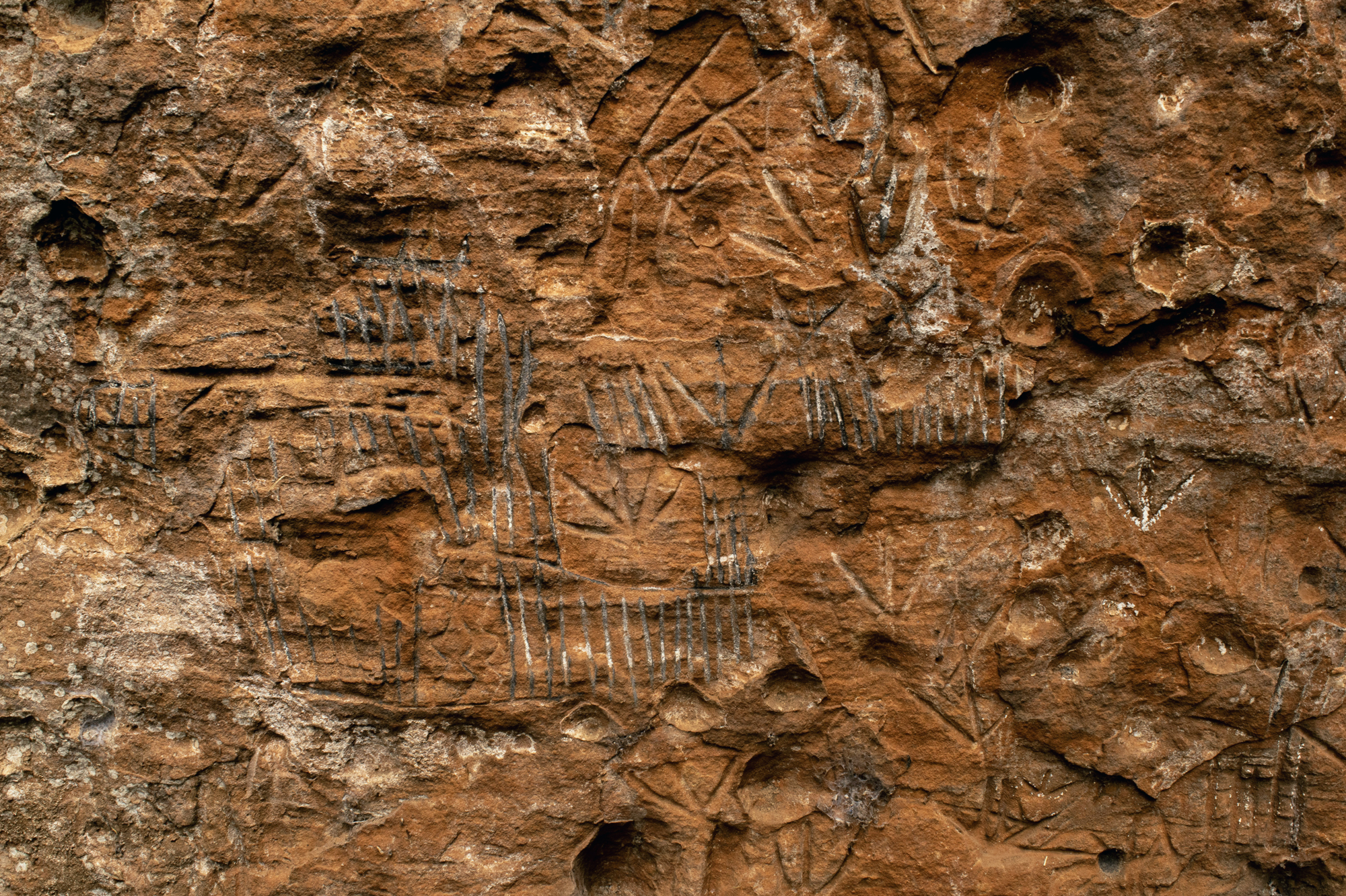

The petroglyph panels belong to the Southern (Meridional) Tradition, a widespread system of petroglyph production that extends from the highlands of Rio Grande do Sul through Santa Catarina, Paraná, and São Paulo states, and into northern Argentina and Uruguay. Within this broad tradition lies the distinctive Pisadas style, so named because of the prominence of engraved tracks, tridactyl bird footprints, feline-like paw marks, and occasional ungulate impressions, rendered with remarkable consistency. At Pedra Grande, these motifs unfold across a 24-meter frieze that rises more than 2 meters. Techniques vary across the surface: deep pecking creates well-defined grooves; scraping produces smoother, shallower channels; polishing sharpens edges or forms lenses and crescentic depressions; drilling produces circular cavities of regular diameter. Some figures preserve residues of white and black pigments, rare survivals that suggest not only engraving but occasional painting. The result is a panel that is both tactile and visual, registering different tool gestures on distinct parts of the rock. The repertoire extends way beyond tracks: circles divided by internal lines, crescents, cupules, elongated grooves, ellipses, and geometric combinations compose an ordered field of forms. The carvings populate the rock surface with great density, bordering horror vacui. Yet, they maintain a spatial logic that implies structured production episodes and aesthetic criteria recognizable within the broader Southern cultural horizon.

Archaeological excavations at Pedra Grande reveal a site shaped not by a single continuous occupation but by successive waves of human presence, separated by centuries yet bound through their encounters with the same rock shelter. The earliest phase, dated to roughly 900–790 B.C., is represented by hearths, charcoal, seeds, and stone tool remains. The hunter-gatherer groups of this period are the most likely authors of the earliest engraving episodes. A refitting fragment found deep in the excavation tells us something crucial about Pedra Grande’s earliest visitors. The piece, carved with the same motif as the main panel, fell from the wall long before the oldest habitation layers formed on the shelter floor. This means the rock art predates the site’s earliest known archaeological signal of occupation. In practical terms, hunter-gatherers were engraving the outcrop before they ever lived beneath it. They stopped here first as travelers, pausing at a striking landmark, marking the stone, and moving on, long before later groups settled in and left the fuller archaeological signature of daily life.

A second occupation, between A.D. 1110 and 1190, attests to renewed presence. Whether these groups continued earlier engraving traditions or simply used the shelter without modifying the panel remains uncertain; however, exfoliated wall fragments with carved perforations in later layers suggest that carving persisted into the second millennium A.D.

A third occupation, dated to A.D. 1305–1385, was associated with Tupiguarani agriculturalists, identified by characteristic ceramic fragments. The presence of exfoliated petroglyph-bearing flakes in these levels, some with drilled pits identical to motifs in situ, indicates that the rock art remained visible, meaningful, and perhaps rock-art-making was still active at least into the early Tupiguarani phase. The Pedra Grande is, in effect, a millennia-long project: generations of visitors returned to the same rock, carving it diachronically across shifting cultural worlds. Whatever its original meaning, each group reinterpreted and reworked it, leaving a record shaped as much by continuity as by transformations.

In the 17th century, Pedra Grande became entangled in colonial and missionary history. On the south and west sides of the monolithic block lie the remains of the Jesuit-Guarani Reduction of São José do Itaquatiá (1633–1637). Jesuit letters preserved in the De Angelis manuscripts describe a small settlement: a church built beside the rock; housing for Jesuit priests; cattle enclosures; and cultivated fields. Around 600 Guarani families lived nearby during the mission’s brief existence. The settlement was abandoned due to bandeirante (part explorers, part slavers) incursions characteristic of the early mission era.

Archaeologically, the mission is visible today through surface ceramics and structural remnants, though no evidence indicates that the Guarani people carved the panel. The petroglyphs, therefore, belong to earlier populations, even as later communities inhabited, reinterpreted, and reshaped the surrounding landscape. The proximity of prehistoric art, Tupiguarani ceramics, and Jesuit mission remains creates a rare three-tiered historical depth typical of complex cultural landscapes: hunter-gatherer engraving, agricultural village life, and colonial-Guarani missionization, all converging around a single sandstone massif and the Toropi River.

The Southern Tradition forms one of the most extensive and most internally cohesive rock-engraving systems in South America. Its geographic distribution reveals a preference for arenitic escarpments, rock shelters, and exposed ledges that offer accessible carving surfaces. The tradition is dominated by geometric motifs: straight lines, parallel bars, circles, spirals, ellipses, grids, and branching forms. The Pisadas style, however, is among its most striking subgroups.

Track motifs (tridactyl, quadrupedal, ungulate, and sometimes human) appear in sequences that mimic trails. Their persistent recurrence across widely separated sites suggests shared symbolic understandings, linked to animal presence, cosmological narratives, territorial marking, or perhaps shamanic tracing. The Pedra Grande is a benchmark site within this style: not only because of the scale of its panel, but also because of the presence of pigment, the diversity of engraving techniques, and the coexistence of major and minor panels on the same outcrop. Its visual vocabulary displays a sophistication that parallels other major Pisadas sites, such as the Morro do Avencal site, yet remains unique in its density, scale, and preservation.

Recent initiatives aim to create a more structured framework for the preservation and public interpretation of site RS-SM-07, a.k.a Pedra Grande. Plans include visitor pathways, interpretive signage, and protective infrastructure designed to mitigate the effects of rain, sun exposure, and the exfoliation common in sandstone formations. A digital archive is being assembled to consolidate decades of dispersed documentation, including photographs, tracings, excavation data, and historical references, into a coherent online resource. While no digital surrogate can replicate the sensory immediacy of standing before the carved panel, documentation enhances accessibility and, as everyone knows, is an indispensable conservation tool. The site’s layered significance, integrating prehistoric art, Indigenous history, and the archaeology of a Jesuit-Guarani mission, creates a cultural landscape that, like all rock art settings, calls for careful and informed stewardship. Encouragingly, that stewardship is beginning to take real root here. The initiative’s website brings together a rich collection of photographs, records of community workshops, and a solid body of material on archaeology, paleontology, geology, and heritage in central Rio Grande do Sul. It’s a rare example in Brazil, an excellent resource, and well worth a visit.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ Brazil Rock Art Archive

→ The Lajedo de Soledade

→ The Rock Art of Pedra Grande

→ the Rock Art of Serrote do Letreiro

→ The Ingá Rock

→ The Peruaçu National Park

→ The Poty River Canyon Petroglyphs

→ Rock Art of Serra da Capivara

→ Rock Art of Pedra Furada

→ The Rock Art of Santa Catarina

→ South America Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network