of the Souza Basin ca. 140 Ma

A remarkable convergence of conditions thus preserved an extraordinary concentration of dinosaur tracks in what is now the Brazilian state of Paraíba. Millions of years later, a new being appeared. This nearly hairless primate, native to Africa but by then spread across the globe, entered this landscape. Skilled hunters, they rose to the top of the food chain wherever they went and, in a matter of a few centuries, expanded from Siberia to Patagonia. In the recent millennia, one of these groups encountered the petrified footprints on the easternmost portion of South America. Faced with traces of creatures they could never have known, they responded by marking the stone with enigmatic symbols, inscribing their own presence beside a record of life from a vastly deeper past.

As of 2025, Serrote do Letreiro stands as the most compelling known association between rock art and fossilized dinosaur tracks anywhere in the world. Associations between rock art and fossilized footprints are exceedingly rare but have been documented on nearly every inhabited continent; none, however, display the same degree of integration or the same close spatial relationship between the two records as observed in Paraíba, Brazil. This is not to diminish other remarkable sites where rock art appears near fossils. In Australia, for example, Herbert Basedow interpreted certain petroglyphs as human renderings of dinosaur footprints. In Poland, a dinosaur track occurs at a site once linked to possible ancient occult gatherings. In the United States, petroglyphs and fossil footprints coexist at locations such as Poison Spider Dinosaur Tracks, Parowan Gap, and Zion National Park. The point is simply that Serrote do Letreiro offers the clearest, most spatially intimate, and most self-evident meaningful relationship between two extraordinary records separated by millions of years. In many of the other instances, it remains unclear whether past peoples were aware of the fossilized dinosaur tracks, as they are not always readily evident, or whether any cultural meaning was attributed to them. At Serrote do Letreiro, however, the attribution of meaning is beyond reasonable doubt.

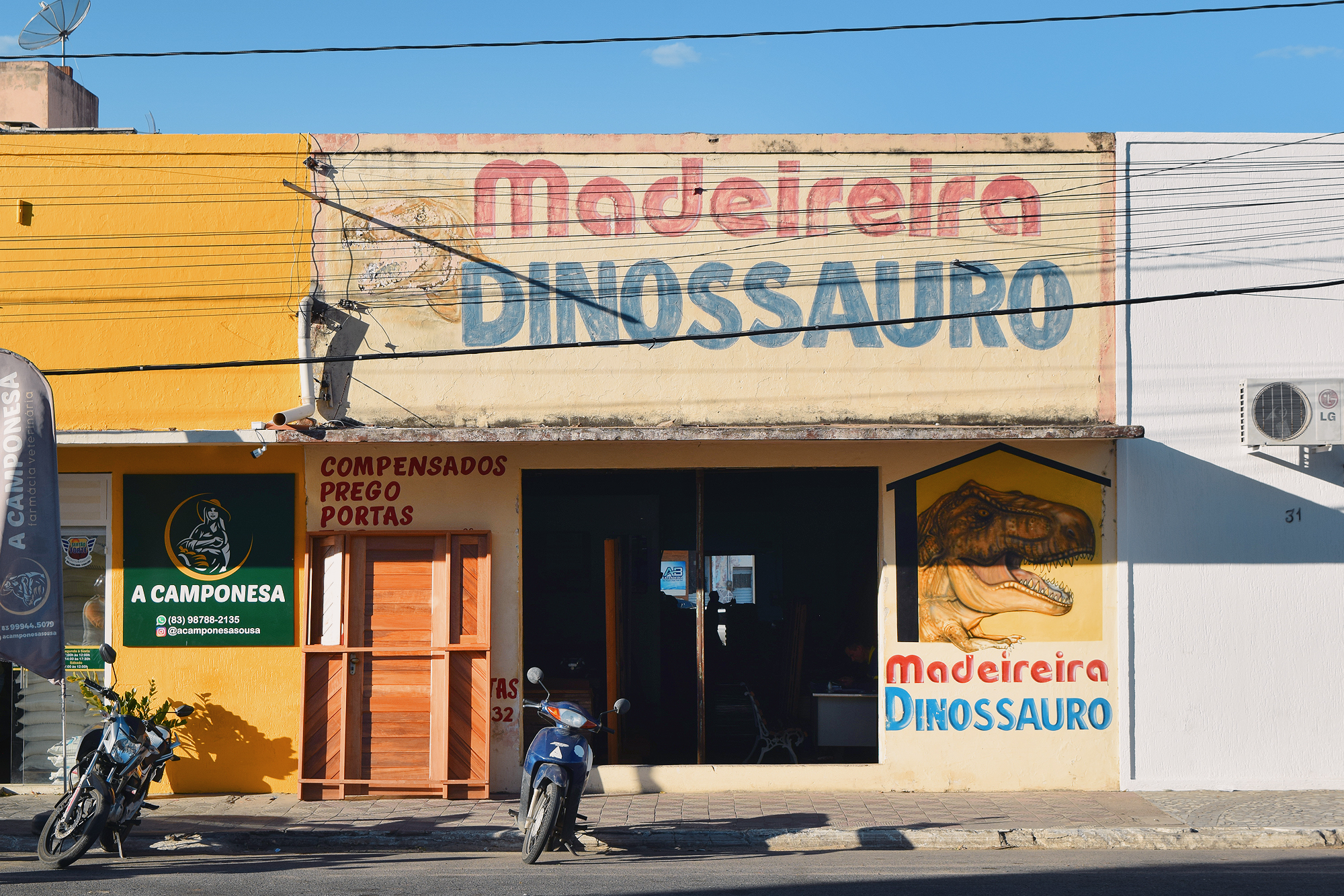

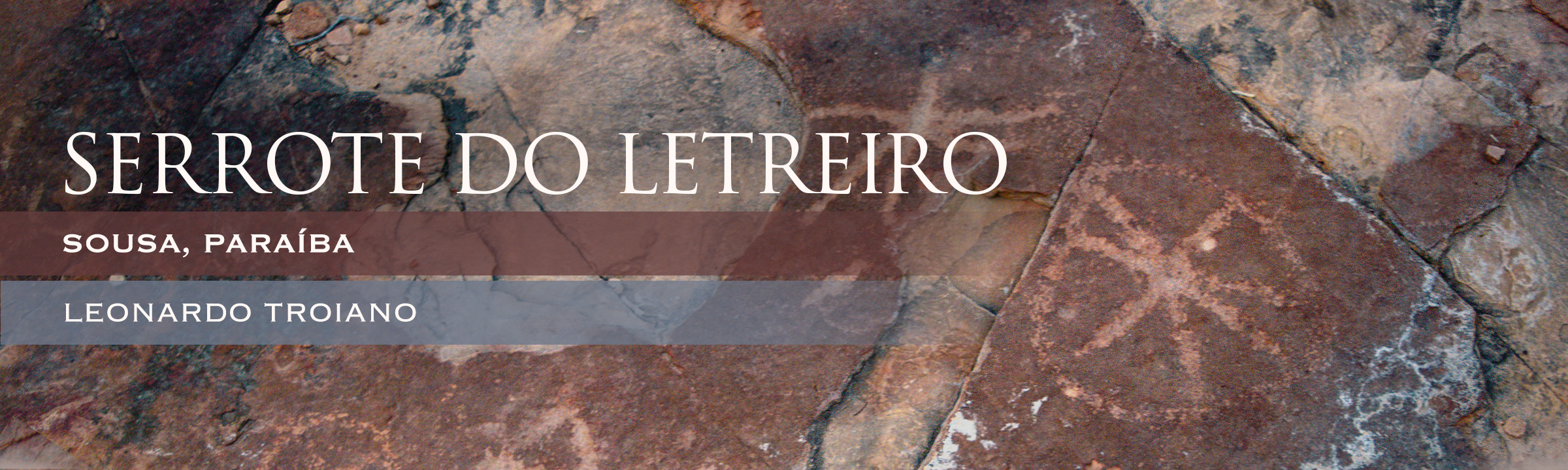

Spread across three rock outcrops dating to approximately 140 million years ago, the “small hill with many letters” (Serrote do Letreiro) preserves a spectacular assemblage: an extended sequence of quadrupedal, long-necked sauropod tracks forming a true herd; numerous bipedal theropod footprints; fossilized wave impressions from an ancient lake; tracks of large duck-billed dinosaurs; and a variety of other ichnofossils, that is, preserved records not of an animal’s body, but of its actions in life.The rock art itself is modest if compared to other sites of the Letreiro tradition, such as the Pedra Pintada site. Permanently exposed to rain and intense sunlight that cause drastic temperature fluctuations and, consequently, cracking and flaking of the rock surface, the petroglyphs are simple, abstract, and eroded. Yet their significance lies not in stylistic flourish, which is inherently subjective, but in their extraordinary placement. Often only centimeters from the fossil tracks, the engravings never cut across or damage the footprints. Instead, they incorporate the dinosaur impressions into the human composition, treating them as features of the landscape worth marking and highlighting rather than effacing them.

In northeastern Brazil, in the most arid reaches of the Sertaneja Depression, a landscape often compared to Australia’s outback, a distinctive type of rock-art site is common. Locals have long called such places letreiros (“bunch of letters” or “many letters”), a name that gestures toward the superficial resemblance between their petroglyphs and alphabetic characters. Since early colonial times, residents have generally believed that these markings represent some form of Indigenous writing. We now know that there is no evidence for this: the motifs are abstract signifiers, and the referents they once pointed to have vanished along with the cultural system that sustained them. The corpus of letreiro petroglyphs may appear monotonous at first glance. Still, a closer look reveals an arresting variety of geometric signs and an equally rich set of recombinations among them. Foremost is the internally divided circle, ubiquitous at all letreiro sites, rendered in seemingly endless permutations: quartered into four equal segments; split by radiating “pizza-slice” lines; divided asymmetrically, as in the central circle at Serrote do Letreiro; and many other variants. The repertoire also includes dots, triangles, line-linked figures, concentric circles, W-shaped forms, serpentine motifs, flower-like designs, forked elements, star-shaped patterns, and rectangles of every proportion. Together, these elements compose a geometric vocabulary of remarkable breadth, one for which systematic nomenclature and classification have yet to be developed.

affiliated with those at Serrote do Letreiro

Very little is known about the society that produced this rock art. From the distribution of these sites, we know that the groups who made this rock art occupied a region roughly the size of modern-day Austria, spanning the Brazilian states of Pernambuco, Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará, and Paraíba. Their preferred canvases were unmistakably consistent: horizontal rock surfaces of flat or gently undulating outcrops known as lajedos; the tops of small hills called serrotes; and large boulders in dry riverbeds, the matacões. These locations differ sharply, for instance, from the itacoatiara petroglyph tradition, also present in Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte, and best exemplified at the iconic Ingá Rock site. Itacoatiara engravings are highly polished, often large, carved into extremely hard vertical surfaces, and placed in close relationship with water. Their motifs are abstract but frequently incorporate figurative or representational elements.

The letreiro engravings, by contrast, are pecked or scraped, rarely polished, onto horizontal surfaces fully exposed to the region’s dry climate and intense sunlight, and their repertoire of motifs could not be more distinct. We must beware that not all “geometric” or “abstract” rock art is created equal. Despite these apparent contrasts, archaeologists have long tended to group all northeastern petroglyphs under the blanket term “itacoatiaras,” a simplification that obscures the true diversity of rock art in the region.

Two factors have fostered this neglect. First is the challenge of highly abstract imagery. Because much archaeological research is driven by interpretation and meaning-making, scholars often gravitate toward painted traditions with more legible, representational figures. Abstract petroglyphs offer fewer interpretive footholds, and their resistance to decoding has frequently pushed them to the margins of research. Second are geographical and historical conditions. These engravings occur in some of Brazil’s harshest environments, shaped by extreme drought, chronic poverty, and long-standing political and academic neglect. Regions lacking basic infrastructure rarely attract sustained archaeological attention. As a result, letreiro sites have remained not only physically remote but also intellectually peripheral, despite their beauty, richness, and archaeological significance.

Their chronology remains elusive, and because the groups responsible for letreiro petroglyphs left behind little more than rock art, and perhaps stone tools, we can only infer that they were nomadic hunter-gatherers who lived in northeastern Brazil at some point within the last 12.000 years. Drawing on the chronologies of the region’s two major rock-art traditions, we can attempt a cautious extrapolation and tentatively place these groups between roughly 9.000 and 3.000 years ago. This range is far broader than ideal, but until reliable scientific methods for dating petroglyphs are invented, it is the best framework we have.

Adrienne Mayor’s The First Fossil Hunters (2000) and Fossil Legends of the First Americans (2005) posed a set of questions that, at the time, were both bold and unconventional: did ancient peoples encounter the fossil record, and if so, did those encounters carry meaning? Those questions lingered. They gained unexpected traction through an encounter with Brazilian geological literature, where a single, easily overlooked photograph in the SIGEP catalogue (Brazilian Commission on Geological and Paleobiological Sites) captures a fossilized dinosaur footprint lying beside a circular petroglyph.

The association is mentioned only in passing: “Kariri Indian petroglyph next to footprint”, as though it were incidental. It was not. The image was published by Giuseppe Leonardi, an Italian priest, indefatigable paleontologist, and the undisputed founder of ichnology in northeastern Brazil, whose expeditions across the interior of Paraíba in the 1970s revealed an astonishing density of dinosaur tracksites. Among them was Serrote do Letreiro, a site he published in 1975 for its paleontological richness alone. Only decades later, as renewed fieldwork expanded Leonardi’s original documentation and brought fresh attention to the region, did the full significance of the site emerge: not merely as a record of deep time, but as a rare and compelling intersection between fossil traces and human mark-making. Work in the region made it possible to preserve and prepare for visitation a number of sites in what is now known as the Dinosaur Valley State Park.

Serrote do Letreiro lies on a small, family-owned property led by its matriarch, Dona Alzenir, who lives there with several generations of her family. The relationship between researcher and community is unusually intimate, marked by affection and trust rather than formality; Ghilardi is affectionately called a “god-given granddaughter.” The site itself is modest in scale. Beyond an old wire fence, a short walk leads to outcrops where large theropod tracks emerge from stone laid down 140 million years ago. On their own, such footprints inspire awe. Encountered alongside ancient petroglyphs carved into the same surfaces, they produce something rarer: a much more palpable sense of temporal depth, where human mark-making and deep-time traces intersect.

Its significance, however, lies less in spectacle than in implication. Brazil’s National Institute for Historic and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN) has long privileged colonial architecture and artistic monuments, reflecting a strongly Eurocentric definition of heritage. Archaeological management within the institution is relatively recent, and paleontological heritage has remained even more precariously positioned. This institutional neglect mirrors a broader disciplinary legacy. As Adrienne Mayor (2005) has shown, paleontology historically relied on Indigenous knowledge to locate fossil sites while systematically dismissing Indigenous interpretations. Even when long-present communities encountered fossils, they were assumed to lack the capacity or inclination to recognize their significance. Serrote do Letreiro directly challenges that assumption.

Research at the site has focused not on fossils or rock art in isolation, but on their relationship, that is, on the likelihood that ancient peoples recognized fossilized tracks and responded to them symbolically and in meaningful ways. This shift, supported by dialogue with earlier work on fossil folklore, reframes the site as an encounter between human sensibility and deep time rather than a coincidence. The implications are substantial. Under IPHAN’s Ordinance No. 375, paleontological sites must be protected when meaningful relationships between human groups and fossils can be demonstrated. Few cases meet this criterion more clearly than a site where people engraved rock art (arguably the most symbolic form of prehistoric expression) directly alongside dinosaur footprints. The international response followed swiftly. In 2024, research on Serrote do Letreiro appeared in headlines in more than 150 countries, and Archaeology Magazine named it one of the world’s ten most significant archaeological works of the year, the only rock-art site on the list. This sudden visibility forced Brazilian authorities and heritage officials to confront an unfamiliar and often overlooked category of heritage, one far outside their habitual focus yet no less significant than any colonial-baroque church.

feature at the Serrote do Letreiro site

A familiar exchange often opens conversations about archaeology. Asked what one does, the answer “I’m an archaeologist” is frequently met with enthusiasm for dinosaurs. The confusion between archaeology and paleontology is longstanding, and it reflects a broader public misunderstanding of the aims and methods of both fields. There are, however, situations in which the two disciplines must work together and do so to mutual benefit. While archaeological and paleontological fieldwork share certain practical rhythms, they are guided by different ways of reading landscapes and by attention to different kinds of traces, often at different scales. Both, nonetheless, confront the material remains of the past.

In contexts involving geologically recent faunas and floras, particularly within the span of human deep time, from the emergence of Homo sapiens to the end of the last Ice Age, collaboration is not merely helpful but essential. The potential for such joint work extends across many site types and chronological settings. Archaeologists would do well to remain attentive to the broader geological contexts in which they work, where paleontological expertise may prove decisive. Paleontologists, in turn, should remain alert to the possibility that fossil sites may preserve evidence of prior human engagement, subtle traces of how earlier peoples encountered, interpreted, or altered the remains of ancient life. Serrote do Letreiro offered a particularly instructive case of this convergence. The work there benefited from close collaboration among paleontologists Aline Ghilardi and Tito Aureliano and archaeologist Heloísa Bitú. It also included a local heritage education initiative, during which Pedro Arcanjo and Renan Xandú, then fourteen and fifteen years old, contributed substantially to the photographic documentation used in the site’s published record.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ Brazil Rock Art Archive

→ The Lajedo de Soledade

→ The Rock Art of Pedra Grande

→ the Rock Art of Serrote do Letreiro

→ The Ingá Rock

→ The Peruaçu National Park

→ The Poty River Canyon Petroglyphs

→ Rock Art of Serra da Capivara

→ Rock Art of Pedra Furada

→ The Rock Art of Santa Catarina

→ South America Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network