Anna Clark

Creative Director, Blunt Crayon (Creative Design Studio)

George H. Nash

Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology, University of Liverpool

Map of Rowtor Rocks (west of Birchover), physically delineated by a stone walled boundary that formed the extent of our survey

Although later prehistoric rock art is known in Derbyshire, little in-depth research has recently taken place. In the autumn of 2024, and through early to mid-2025, the authors undertook a walkover survey in and around Rowtor Rock, a tor-like feature located immediately west of the village of Birchover (Clark & Nash 2025). This survey was the result of the discovery of engraved marks, possibly representing the outline of an animal. In addition to the initial discovery of an engraved animal, the walkover survey also discovered a further figurative engraving; however, both figures are not common with the later prehistoric repertoire of the British Isles.

The walkover survey, extending over three separate visits, recorded a sufficient number of engraved sites to identify several distinct clusters located across the lower, intermediate, and summit zones of Rowtor Rocks. Setting aside the two earlier figurative engravings, the cervid and the bovine, the majority of the recorded markings consisted of late Neolithic/Bronze Age motifs, alongside historic and modern graffiti.

Several of the sites recognised by Barnatt & Reeder (1982) and Bevan (1995) are included in the Clark and Nash inventory, collectively forming an assemblage of 44 sites which were distributed across an area measuring roughly 245 by 110 metres (Clark & Nash 2025) (Figure 1). We would stress at this point that, despite the discovery of a large number of individual engraved panels, more prospection is needed to assist in understanding the distribution of the basic motif repertoire (i.e., cupmarks) and the relationship between rock art, landscape and nearby contemporary stone monuments.

The rest of the assemblage though is non-figurative and belongs to the Atlantic tradition that dates between the Neolithic and Bronze Age periods (Valdez-Tullett 2019). Simple motifs, such as cupmarks also feature in the Megalithic art repertoire, usually associated with stone chambered monuments (Nash 2019; Shee-Twohig 1981). Cupmarks are by far the most common motif occurring in the British Isles during the later prehistoric period (e.g., Beckensall 1999; Morris 1989; Nash, Allen & Bowen 2024; Sharkey 2004). Their meaning, of course is unknown; however, their coverage, between Spain and Portugal and southern Scandinavia, a distance of 3,200 km suggests a well-established universal meaning for this simple motif.

The Derbyshire Peak District, forming part of the southern reaches of the Pennine uplands, encompasses not only central Derbyshire but also adjoining areas of north Staffordshire, east Cheshire, and south Yorkshire. This predominantly upland landscape served as a significant locus of human activity during the Neolithic and, more prominently, the Bronze Age. Within this temporal and spatial context, prehistoric communities constructed stone monuments and established burial sites that reflect complex ritual and cosmological engagements with the land. At this time, the uplands of the northern Midlands were being cleared by these early farming communities, used for small settlement units, animal grazing and sporadic cultivation (e.g., Swine Sty and Mam Tor).

As an extension of these ritualised practices, certain locales were demarcated for the creation, inscription, and possibly performance of rock art, acts that suggest deeply embedded symbolic, social, or spiritual functions. While the precise meanings of these motifs remain elusive to contemporary interpretation, and the rationale for their specific spatial placements is inherently speculative, what can be affirmed is that the majority of recorded rock art in Derbyshire, consistent with wider regional traditions, is engraved into millstone grit [sandstone] substrates (Beckensall 1999; Morris 1989). These carvings, situated within enduring landscapes of memory and meaning, contribute to a multilayered archaeological palimpsest, an accretion of cultural practices inscribed over millennia, each leaving traces that inform and complicate our understanding of deep historical processes (see Tilley 1994).

Geologically, Rowtor Rocks is composed of millstone grit, a coarse-grained sandstone dating back approximately 320 million years to the Carboniferous period (BGS; Smith et al. 1967). This resilient rock is a defining feature of the Peak District landscape. Rowtor Rocks is a classic example of a tor formation, similar in character to those found on Dartmoor and is constructed by the regional geology – millstone grit. To its west lies another outcrop bearing evidence of prehistoric rock art, suggesting a broader cultural pattern in the area.

Over millennia, the region’s exposed rocks have been heavily weathered by natural forces, the result of frost, wind, and chemical erosion, creating the rounded boulders, fissures, and overhangs visible today. The once-present soils have long since been washed or blown away, revealing the sculptural forms of the upland terrain. Rich in quartz and feldspar, and cemented with silica, the rock’s course, durable surface proved ideal for ancient engravings, now beginning to re-emerge from the landscape’s stony silence.

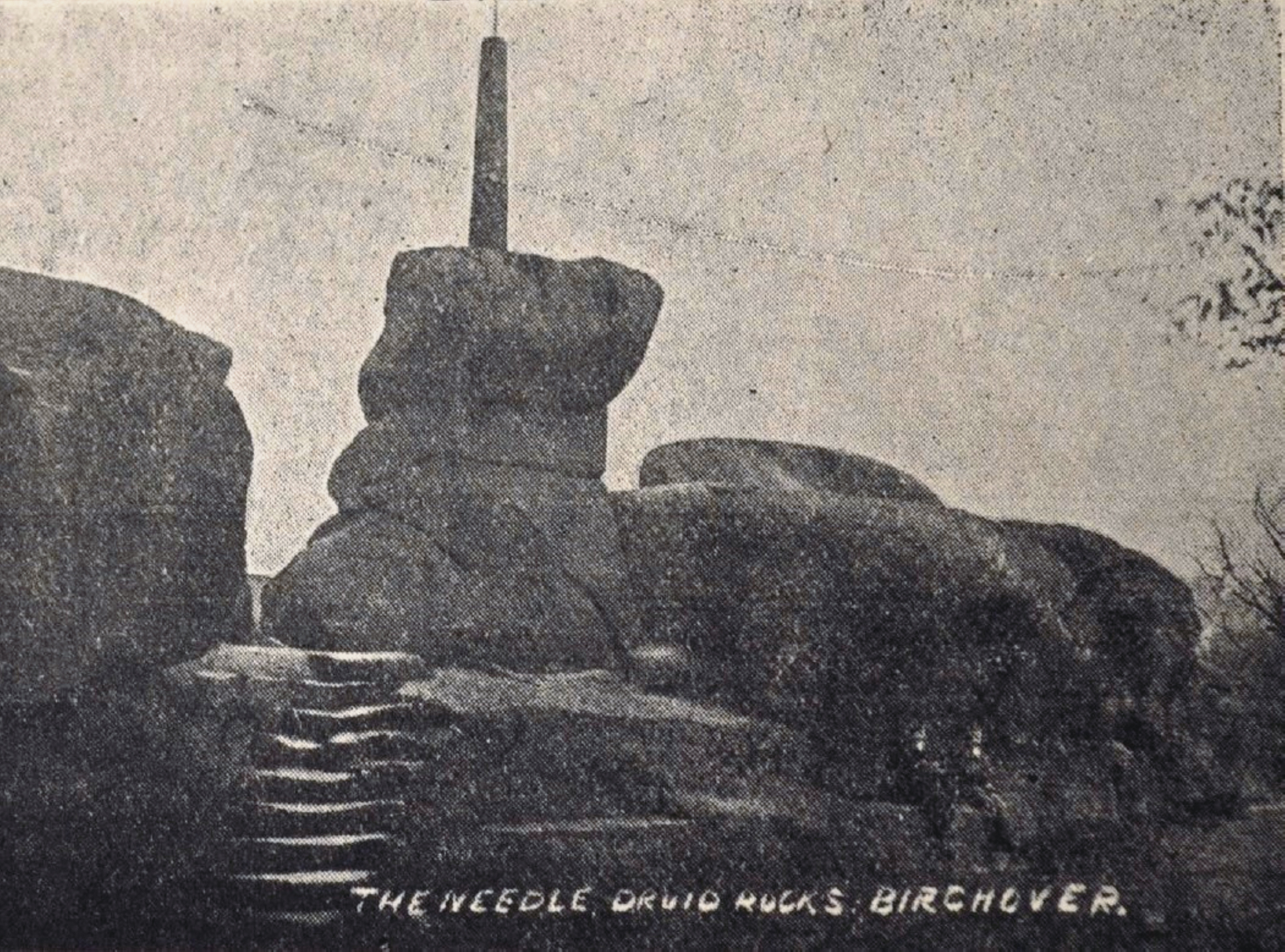

Early 20th century postcards showing

the summit of Rowtor Rocks

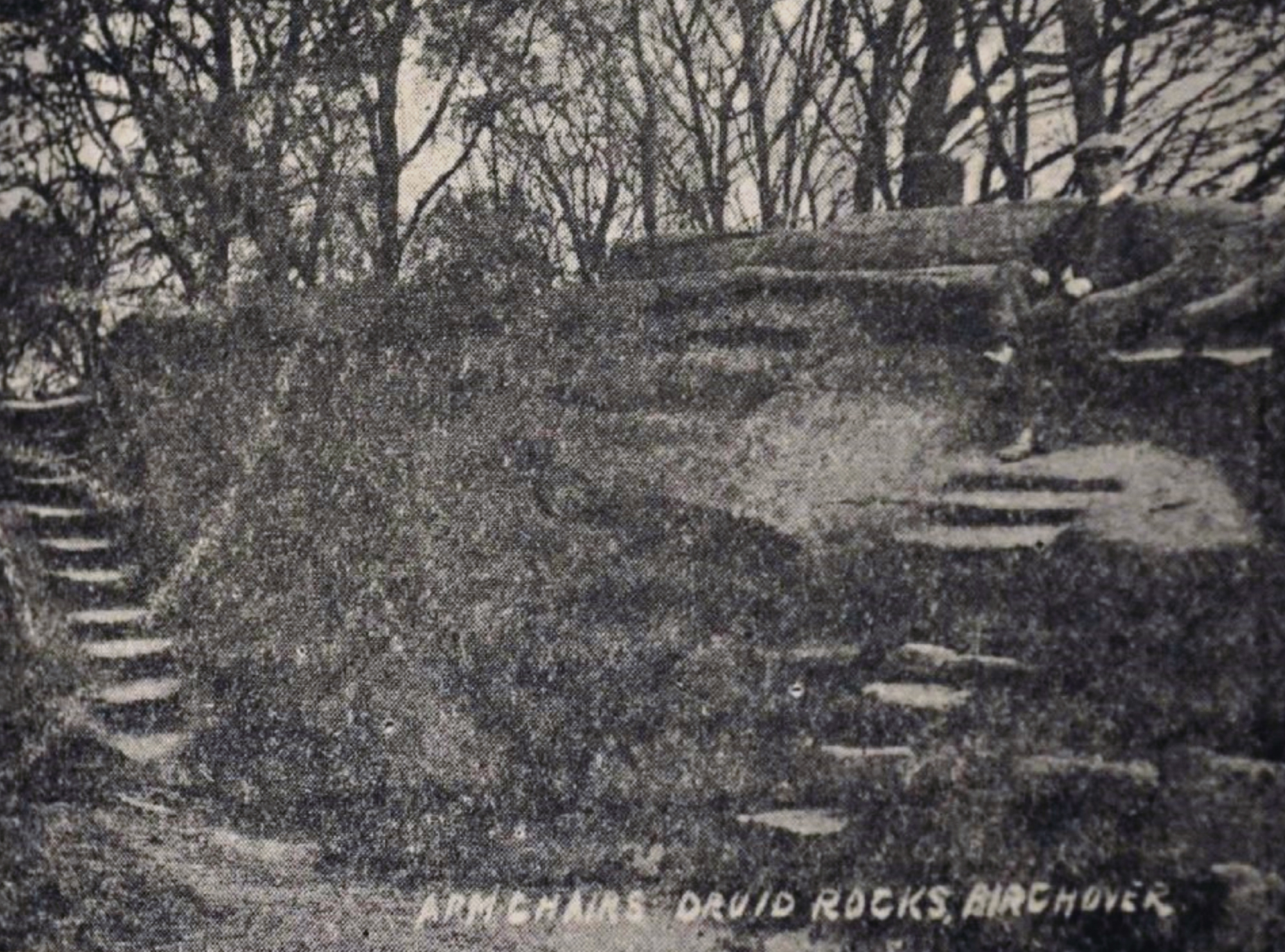

Early 20th century postcards showing

the summit of Rowtor Rocks

Two of the many sculptured features

that are cut into Rowtor Rocks

Two of the many sculptured features

that are cut into Rowtor Rocks

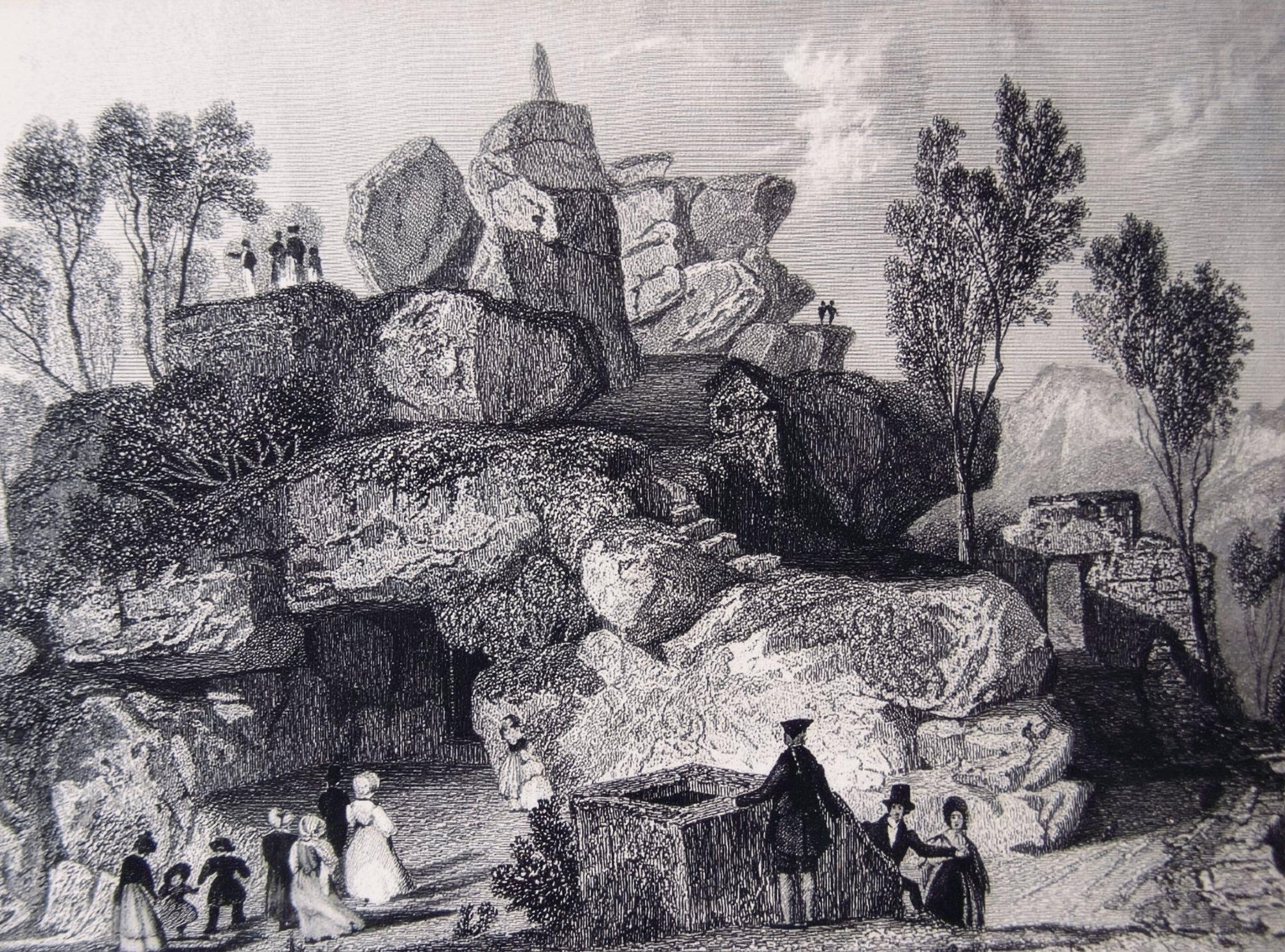

Copperplate engraving of the cave,

located at the eastern end of the Rocks

Topographically, Rowtor Rocks occupies a prominent elevated position, commanding wide views over the moorlands and valleys of the southern Peak District. Rising to approximately 305 metres AOD, the tor is defined by an irregular terrain shaped by a combination of natural erosion and later human modification. Although the tor and its immediate landscape is covered by native trees and shrubbery, the area was treeless during the latter part of the 19th century and the early 20th century – based upon postcards of the time (Figure 2 & Figure 3). It is more than likely that Rowtor Rocks was cleared of vegetation during the time when rock art was being engraved and venerated during the Bronze Age. The openness of the landscape would have provided greater intervisibility with neighbouring topographic features, such as Robin Hood’s Stride and Stanton Moor.

Aligned roughly east to west, the formation consists of a chaotic assemblage of stacked gritstone blocks, creating a labyrinth of narrow passageways, small caves, and deep crevices. Many of these rocks bear signs of deliberate sculptured alteration, carved steps, platforms, seats, and even hollowed-out rooms, made by human agency (Figure 4 & Figure 5). Coupled with these ornate features are a series of drystone walls that may have had a land division function. These alterations are believed to date from the 17th or 18th century and coincide with several artistic landscape movements (Anon 2018).

These modifications are commonly attributed to Thomas Eyre (b. 1645? - d. 1717), a former owner of the nearby Rowtor Hall estate. Eyre is thought to have reworked parts of the tor in line with the aesthetics of the Picturesque movement, then popular among the educated elite, blending natural drama with romanticised notions of ancient landscapes (Anon 2018; Barre 2017; Heathcote 1934) (Figure 6 & Figure 7).

Prior to initiating a broader walkover survey of Rowtor Rocks, we initially focused on a particularly intriguing feature: a jumble of engraved and natural lines etched into a near-vertical rock panel, representing a stylised side-on cervid. This panel forms part of a large gritstone block situated just west of a well-trodden path on the southern side of the tor. Prior to this discovery, archaeologist Hamish Fenton made a remarkable find in 2012, that included a [family?] group of red deer engraved on the underside of a capstone at the Dunchraigaig Cairn in Kilmartin Valley, western Scotland (Valdez-Tullett et al. 2023). Although the engravings were considered to be from the Neolithic period, and therefore, contemporary with the construction and use of the cairn, the stone itself may have originated from a much earlier context. The Dunchraigaig Cairn engravings are considered to be the first of this date to be found in mainland British Isles.

A site visit to Rowtor Rocks in April 2025 confirmed that the engraving likely depicts an adult cervid, possibly a reindeer but more plausibly a red deer. The first indication of the figure’s archaeological significance came with the identification of a curving line interpreted as the animal’s underbelly - a distinctive and deliberate mark that stood out clearly from the surrounding natural striations, cracks and grooves (Figure 8 & Figure 9).

To better understand the figure, the engraving was recorded under varying light conditions, both during daylight and after dark. Despite careful observation, the full outline remains partially obscured due to heavy weathering, particularly in the areas representing the antlers and the rear section of the animal. However, recording during hours of darkness revealed the outline of a muzzle, crown, and neck, along with a small depression representing an eye (Figure 10). Although the side-on figure was initially identified, subsequent observations also revealed a smaller cervid - probably a juvenile, immediately to the rear of the larger figure.

This composition, featuring an adult and juvenile cervid, mirrors scenes depicted on several engraved panels in northern Scandinavia, many of which are attributed to the Mesolithic period (c. 9500–4000 BCE). Notable examples include the Stykket panel in Nord-Trøndelag and the Leiknes panel in Nordland, Norway (Sognnes 2001). Similar engraved scenes are also noted in southern Norway and Sweden; however, these southern Scandinavian examples may date to the Bronze Age or slightly earlier (Coles 1990; Sognnes 2017).

During the Bronze Age in Galicia, northwest Spain, a distinctive tradition of red deer engravings emerges, typically found on exposed, angled, or horizontal rock panels. These depictions form part of a broader and diverse repertoire that includes both figurative and non-figurative imagery, such as boats, horses, human figures, and weaponry, with red deer playing a particularly prominent role in the iconography relevant to this section of our study. The representations of red deer are predominantly of adult stags, often characterised by prominently rendered antlers that emphasize their masculinity and possibly their symbolic status. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no known depictions within this tradition that show adult and juvenile deer together, distinguishing it from other traditions where familial or age-group pairings are more explicitly portrayed.

While the engraving at Rowtor Rocks cannot currently be dated through scientific methods, its stylistic similarities to the Scandinavian examples may provide tentative clues to its possible chronological placement.

Based on archaeological evidence from the region, it is conceivable that hunter-fisher-gatherer communities inhabited this upland area of the northern Midlands during the early Holocene, a time when the climate was rapidly warming (Lewis 2009). Cold-tolerant birch and pine forests were gradually replaced by broad-leaf woodland, dominated by alder, hazel, lime, and oak. By around 5000 BCE, clearance by small-scale farming groups led to the emergence of heathlands across upland southern Britain.

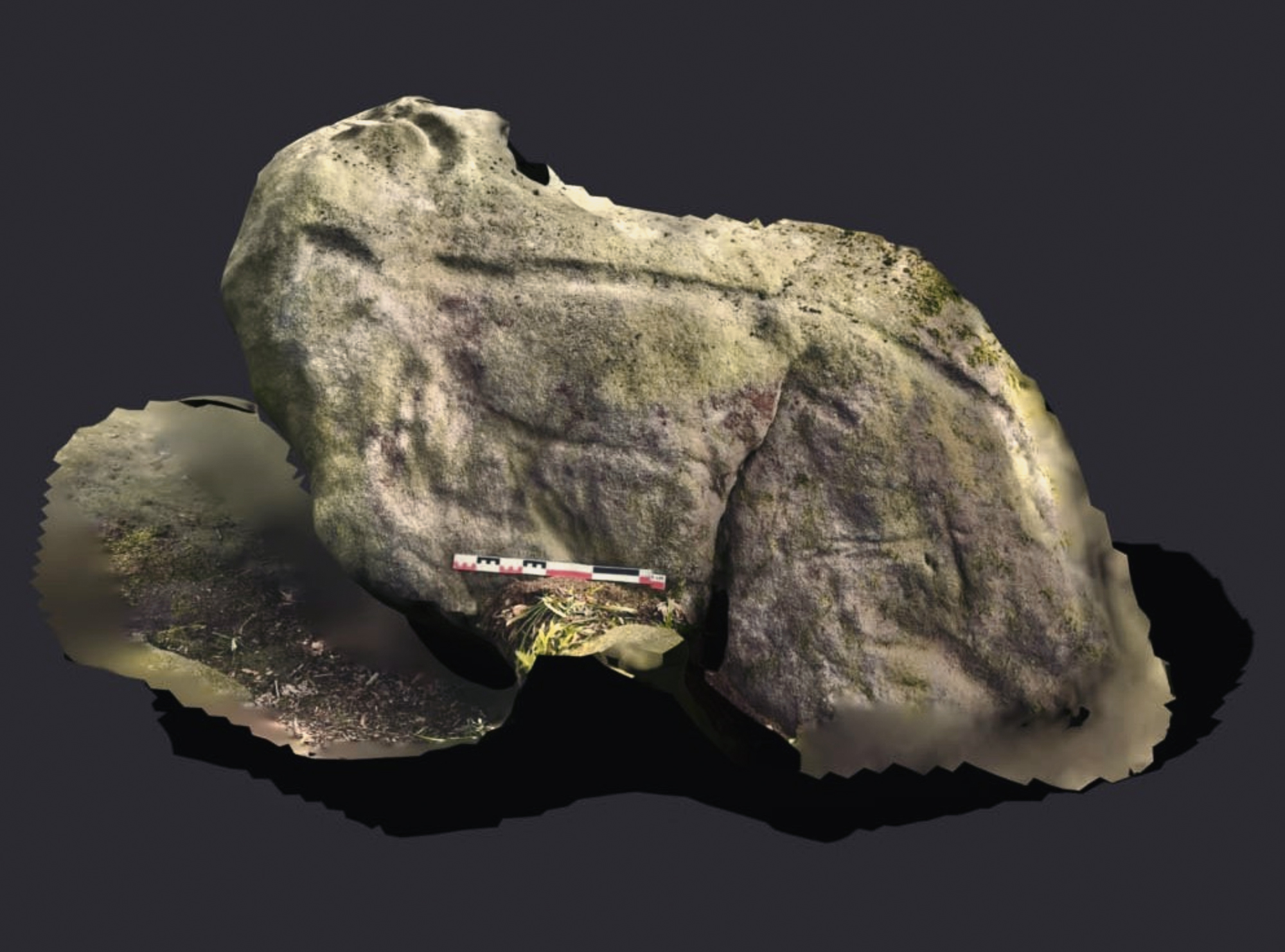

An engraved bovine, hidden within an artificially constructed cave, located on the southern side of the tor

To further support a possible early date for the cervid engraving, the survey team documented another engraved figure - a clear depiction of a bovine, probably an aurochs, located in a small, constructed cave on the tor (Figure 11 & Figure 12). The artificially constructed cave is part of the Picturesque landscaping of the area, undertaken during the 18th century, when Rowtor Rocks became a site of antiquarian and aesthetic interest.

An engraved bovine, hidden within an artificially constructed cave, located on the southern side of the tor

The cave, one of several created or modified during the Picturesque period, uses the eastern wall of a disturbed and realigned section of the natural tor to support large, rounded roofing stones. A constructed western wall completes the structure, while the northern side is defined by the natural downslope of the tor formation.

The engraving itself measures approximately 0.90 metres in length and 0.45 metres in height, and is carved into a sloping, weathered stone block. Key attributes associated with wild aurochs, rather than domesticated cattle, are clearly visible, including the rear section, hind legs, tail, and the characteristic line of the back and underbelly. The forelegs and lower neck are also present. Unfortunately, the head appears to be missing, possibly due to damage sustained during the construction of the cave.

Both engravings make use of the natural characteristics of the rock and conform to each other stylistically. The engravings share a wide and prominent carved outline of the back, and finer engraving lines develop the details. Both engravings make use of the topography of the stone on which they are carved, using natural fissures to give the carvings presence and grounding.

According to the Derbyshire Historic Environment Record (HER), little is known about early prehistoric rock art in the region, specifically engravings and paintings that predate the Neolithic and Bronze Age. While Derbyshire is rich in later prehistoric remains, particularly from the Bronze Age, there is limited archaeological evidence from the earlier periods, including the Early Neolithic, Mesolithic, and Upper Palaeolithic.

However, notable exceptions exist. Approximately 17 km northwest of Rowtor Rocks lie the caves of Creswell Crags, one of the most significant Upper Palaeolithic sites in the British Isles. Here, evidence of both Neanderthal and early modern human activity has been uncovered. Most importantly, Church Hole Cave contains one of three British cave sites with confirmed examples of Ice Age cave art, including engravings of animals such as red deer and bison, some of which have been scientifically dated to over 12,000 BP (Bahn & Pettitt 2009; Pike et al. 2005).

These findings highlight the potential for undiscovered early prehistoric art elsewhere in the region, including open-air sites like Rowtor Rocks, even if current evidence remains limited.

As previously stated, Rowtor Rocks forms part of a wider and richly layered prehistoric landscape. Notable among the surrounding features are Robin Hood’s Stride (centered upon NGR: SK 224 624), located a few hundred metres to the west, and the extant ceremonial monuments of Stanton Moor (centred upon NGR: SK 246 635), approximately 1 km to the north-east, among many others. From certain exposed sections of the summit, both sites are intervisible, reinforcing their spatial and visual connectivity and, by extension, their likely collective ritual or symbolic significance during later prehistory (e.g., Bradley 2009; Tilley 1994).

Robin Hood’s Stride, a dramatic, largely treeless gritstone outcrop, contains several examples of Bronze Age rock art. These carvings, commonly in the form of cup-marks, cup-and-ring motifs, and bowlmarks, appear on both vertical and horizontal rock surfaces. These diagnostic engraving styles are also found on and around Rowtor Rocks, suggesting a shared cultural or symbolic repertoire across the immediate landscape.

In contrast, while Stanton Moor is archaeologically rich, home to several stone circles (including the Nine Ladies and Doll Tor), ring cairns (Stanton Moor I, III, and IV), a prominent standing stone (known as the King Stone), and numerous burial mounds, there is no recorded evidence of prehistoric rock art at the site. Its significance appears instead to derive primarily from its monumental architecture and its central role in funerary and ceremonial practices during the later Neolithic and Bronze Age periods. It is conceivable that this ritualised later prehistoric landscape was approached via Robin Hood’s Stride and Rowtor Rocks, both of which preserve evidence of earlier rock art traditions. These sites may have formed part of a broader ceremonial route, along which communities processed with their deceased, marking the landscape with carved symbols as a form of commemoration and ancestral remembrance.

Prior to the 2025 walkover survey began, a small number of prehistoric carvings had already been recorded at the northern and western sections of Rowtor Rocks. These included classic cup-and-ring motifs, a cup mark with a snake-like groove, and a more elaborate design made up of a central cross surrounded by concentric rings and U-shaped grooves – known as the Rosetta Stone (NGR SK 235 621). These carvings are thought to date to the second or third millennia BCE and are typical of Bronze Age rock art found not only in the Peak District but also across other parts of northern and western Britain (Beckensall 1999; Sharkey 2004; Sharpe 2007).

Most of these engraved panels were found on the northern and southern slopes of Rowtor Rocks. Within these zones, a range of vertical and horizontal rock surfaces, both on the tor itself and on loose or fallen boulders, appear to have been deliberately selected. Cupmarks were typically placed on smooth, horizontal surfaces; however, in the intermediate slope zone, they were also engraved on vertical faces, likely to enhance their visibility when ascending the tor. Very few panels contained only a single cupmark. In cases where this did occur, they were typically surrounded by panels featuring multiple cupmarks, suggesting a broader spatial logic or clustering in the way these features were created and used. Noticeable were also cupmark alignments; a number of the panels clearly revealed three and four cupmarks engraved in a linear arrangement.

The walkover survey had previously identified a number of significant rock art panels, using not only targeted light sources, such as oblique lighting during nighttime hours, but also a mobile application to create 3D models of various panels. The mobile application produced a detailed contour scan across various rock surfaces where extremely faded motifs could not be clearly seen.

One such boulder, situated a few metres east of the ‘Deer Stone’, featured a substantial number of cup-and-ring marks, which were initially thought to be simple cupmarks (Figure 13 & Figure 14), recently named ‘The Druid’s Stone’ . Geologically, this boulder appears to have rolled and settled from the central section of the tor formation's summit over geological time. Close examination of its surfaces, using both oblique lighting at night and the mobile 3D application, revealed multiple cup-and-ring marks on the north-facing surface (which faces the tor formation) and along an east-west ridge forming the upper section of that surface (Figure 15). Despite significant weathering on this particular panel, the cup-and-ring motifs remained visible under artificial lighting. The 3D animation of this large stone block further confirmed the presence of additional cup-and-ring marks on this panel (Figure 16).

In addition to its array of single and multiple cupmarks, cup-and-ring motifs, bowlmarks, and both linear and curvilinear grooves, Rowtor Rocks also features a particularly intriguing, engraved motif known as the Rosetta Stone. Located on the intermediate slope of its southern side, this heavily weathered engraving appears on a horizontal panel and consists of a complex curvilinear motif formed by a double-lined concentric circle. To combat the issues of daylight, the team photographed the motif using oblique lighting and a black cloth that covered the panel (Figure 17) Within the circle, a series of pickets and lines create a symmetrical inner pattern surrounding the inner decorated circle where there are concentric ‘petal’ shapes creating a flower-like appearance. It is likely that the motif was originally more elaborate, but four millennia of weathering have eroded much of its finer detail (Figure 18).

Anna Clark using oblique lighting

methods at the Druid’s Stone

One of two cup-and-rings located along

the upper ridge of the Druid’s Stone

The later prehistoric rock art of the Derbyshire Peak District and elsewhere in the region remains a relatively under-researched archaeological resource, with only a limited number of areas having been subject to systematic investigation (e.g., Barnatt & Reeder 1982; Morris 1989; Bevan 1995; Cockrell 2020). This rock art tradition is exclusively non-figurative, comprising a range of motifs that include cupmarks, cup-and-ring marks, linear grooves and interconnecting lines. The repertoire can be understood as part of a broader assemblage distributed across the hinterlands of the southern Pennines (e.g., Barnatt & Reeder 1982; Guilbert 1989; Guilbert, Garton & Walters 2003, Cockrell 2020). With most examples, later prehistoric rock art is found in association with other types of monuments, such as cairns and barrows, standing stones, stone circles, and stone rows (e.g., Bradley 2009; Fox 1959). Together, they form an integral component of a wider ritual complex centered on death, burial, and ceremonial practice (see Evans 2013, 2022; Mazel & Nash 2022).

As previously suggested, there is a strong possibility that the two figurative engravings at Rowtor Rocks - depicting what appear to be cervid and bovine figures - may date to the Mesolithic or early Neolithic periods. During these prehistoric periods, the surrounding landscape would have offered a hospitable environment for hunter-fisher-gatherer communities, providing access to water sources, shelter, and a rich diversity of flora and fauna (see Conneller 2021; Lillie 2015). The choice of subject matter, specifically, cervids and bovines, is particularly noteworthy, as such animals feature prominently in the rock art traditions of both southern and north-western Scandinavia, where similar motifs are frequently encountered on engraved panels (Sognnes 2017). This broader iconographic pattern may reflect the symbolic or subsistence significance of these animals within early foraging societies. Furthermore, the presence of comparable engravings in the nearby Church Hole cave at Creswell Crags, an important Upper Palaeolithic and early post-glacial site, could lend further weight to the argument for an early prehistoric origin of the Rowtor Rocks figures. While definitive dating remains elusive, the convergence of stylistic, environmental, and regional parallels suggests that these engravings may belong to a much older stratum of artistic expression in the British landscape.

The remaining 42 sites identified by the authors during the 2025 walkover survey are confidently attributed to the Bronze Age, based on both their stylistic characteristics and their spatial distribution. These sites form a coherent assemblage that aligns closely with similar clusters found across Derbyshire and the wider British Isles. The engraved repertoire includes a range of motifs, such as single and multiple cupmarks of varying sizes and depths, cup-and-ring marks, as well as linear elements including grooves and channels (Figures 19, 20, 21, 22). These motifs are distributed across the slopes and summit of Rowtor Rocks, indicating a deliberate placement strategy that may have held symbolic or practical significance.

Among this motif assemblage is a particularly elaborate and enigmatic design known as the "Rosetta Stone", a large, circular engraving located on the northern face of Rowtor Rocks. Its complexity sets it apart from the simpler motifs, suggesting a potentially unique function or symbolic importance within the broader assemblage.

A selection of recorded cupmarked

stones that are located on the

four sides of Rowtor Rocks

A selection of recorded cupmarked

stones that are located on the

four sides of Rowtor Rocks

A selection of recorded cupmarked

stones that are located on the

four sides of Rowtor Rocks

A selection of recorded cupmarked

stones that are located on the

four sides of Rowtor Rocks

Two enhanced smooth-lined

bowlmarks with cut channels,

located on the summit of Rowtor Rocks

Of particular note is the identification of a newly recognised motif, provisionally termed a bowlmark. Several examples of this form have been recorded on the summit of Rowtor Rocks, as well as on the nearby rock outcrop of Robin Hood’s Stride. These bowlmarks often appear to be modified natural depressions, but what distinguishes them is the consistent presence of a deliberately carved channel or groove extending from the rim (Figure 23 & Figure 24). This incision allows water to flow from the bowl and down the rock surface, suggesting a possible ritual or symbolic function, perhaps related to the control or direction of water as a meaningful element within Bronze Age cosmologies or practices.

Together, this diverse assemblage of motifs contribuTogether, this diverse assemblage of motifs contributes to a growing understanding of the complexity and regional specificity of prehistoric rock art in the Peak District and further underscores the cultural significance of Rowtor Rocks as a ritual or symbolic landscape during the Bronze Age.

Exposed tor formation forming the central section of Rowtor on its northern side. Image taken from the Rosetta Stone, looking east

Yet beyond its striking physical form, Rowtor Rocks is imbued with deep cultural and historical significance. Over the centuries, it has been appropriated for a range of human activities, such as ritual practice, shelter, performance, meditation, and artistic expression over at least six millennia or more (representing over 250 generations of community). These uses have left subtle and not-so-subtle traces in the form of rock carvings, cut steps, alcoves, seats, and chambers, some of which blend so seamlessly into the geology that the line between natural and human-made is sometimes blurred.

In the modern era, Rowtor Rocks continues to attract interest as a place of mystery and inspiration. It functions as a popular destination for walkers, climbers, and those drawn to its enigmatic atmosphere, an association shaped in no small part by the influence of Reverend Thomas Eyre in the 18th century. Eyre, the local clergyman and antiquarian, carved various features into the rocks, including seats and hermitage-like cells, enhancing its reputation as a site of contemplation and curiosity.

This sense of mystique was further amplified during the 18th century by its association with the Picturesque movement - a philosophical and aesthetic trend that valued irregularity, dramatic contrasts, and the interplay between nature and artifice. Rowtor Rocks, with its rugged formations and atmospheric setting, fit neatly into this sensibility and was visited by those seeking sublime and romantic landscapes.

Taken together, the physical and cultural elements of Rowtor Rocks form a complex palimpsest of activity. They reflect sustained human engagement and reverence of this upland landscape, from probable Mesolithic figurative representations to Bronze Age motifs and later historical sculpturing. Each layer of use and meaning adds depth to our understanding of the site, revealing it not as a static monument, but as a living, evolving cultural landscape.

The authors of this report wish to thank Natalie Ward (Peak District National Park) and Steve Baker and Dana Campbell (Derbyshire County Council).

- Anon., 2018. Rowtor Rocks: Level 1 survey (August 2018). Report No. AAP6895 Work Placement in Landscape Archaeology Student: 170117421. For the Peak District National Park.

- Bahn, P. & Pettitt, P., 2009. Britain's Oldest Art: The Ice Age cave art of Creswell Crags. Historic England.

- Barnatt, J. & Reeder, P., 1982. Prehistoric rock art in the Peak District, Derbyshire Archaeological Journal. Volume 102, 33-44.

- Barre, D., 2017. Historic Gardens and Parks of Derbyshire. Oxford: Windgather Press.

- Beckensall, S., 1999. British Prehistoric Rock Art, Stroud, Tempus.

- Bevan, B., 1995. Robin Hood's Stride, Harthill and Elton, Derbyshire, archaeological survey, pp 11-12. Commissioned by the Derbyshire Peak District National Park.

- Bradley, R., 2009. Image and Audience: Rethinking Prehistoric Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Clark, A. & Nash, G.H., 2025. Walkover survey for prehistoric rock art across Rowtor Rocks, Birchover, Derbyshire. Unpublished grey literature report, submitted to the Peak Distict National Park and Derbyshire County Council.

- Cockrell, T., 2020. Prehistoric Rock-Art at Spout House Hill, South Yorkshire. Bolsterstone Archaeology and Heritage Group. Unpublished Report.

- Coles, J.M., 1990. Images of the Past: A Guide to the rock-carvings and other ancient monuments in Northern Bohuslän. Uddevalla: Skrifter av Bohusläns Museum och Bohusläns Hembygdforbund 32.

- Conneller, C., 2021. The Mesolithic in Britain: Landscape and Society in Times of Change. London: Routledge

- Devereux, P., Jones, I. & Nash, G.H., 2016. The Curious Case of St Caffo’s Church, Anglesey, Wales, Time and Mind, 9:2, 159-166. Link

- Evans, E.M., 2013. Gelligaer Common Community Prehistoric Rock Art Survey (GGAT unpublished report 2013/018.

- Evans, E., 2022. Prehistoric Rock Art in Glamorgan and Gwent. In A. Mazel and G.H. Nash (eds.). Signalling and Performance: Ancient Rock Art in Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 316-330.

- Fox, C.V., 1959. Life and Death in the Bronze Age. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Guilbert, G., 1999, Recent finds of prehistoric rock-art in upland Staffordshire, West Midlands Archaeology 42, 18-22.

- Guilbert, G., Garton, D. and Walters, D., 2003, Wooton, Gidacre Lane – prehistoric cup-marked stone, West Midlands Archaeology 46, 116-118.

- Heathcote, J.P., 1934. Birchover: Its Prehistoric and Druidical Remains. Chesterfield: Wilfred Edmunds Ltd.

- Lewis, B., 2009. Hunting in Britain: From the Ice Age to the Present. Cheltenham: History Press

- Lillie, M., 2015. Hunters, Fishers and Foragers in Wales: Towards a social narrative of Mesolithic lifeways. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Mazel, A. & Nash, G.H., 2022. Signalling and Performance: Ancient Rock Art in Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Morris, R.W.B., 1989. The Prehistoric Rock Art of Great Britain: a survey of all sites bearing motifs more complex than simple cup-marks, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 55, 48–88.

- Nash, G.H., 2018. Art and Environment: How can rock art inform on past environments? In B. David & I.J. McNiven (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nash, G.H., 2019. The cupmark conundrum: A Welsh Neolithic perspective. Adoranten, pp. 96-112.

- Nash. G.H., Allen, K. & Bowen, D., 2024. Documenting a sacred landscape: Rock art and monuments in the South Wales uplands. Current Archaeology, Issue 410, 42-46.

- Pike, A.W.G., Gilmore, M., Pettitt, P., Jacobi, R., Ripoll, S, and Muñoz, F., 2005. Verification of the age of the Palaeolithic cave art at Creswell Crags, UK. Journal of Archaeological Science 32, 1649-55.

- Sharkey, J., 2004. The meeting of the tracks: rock art in ancient Wales. Gwasg Carreg, Gwalch.

- Sharpe, K. 2007. Motifs, monuments and mountains: prehistoric rock art in the Cumbrian landscape. University of Durham - Unpublished doctoral thesis.

- Shee-Twohig, E., 1981. Megalithic Art of Western Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Smith, E.G., Rhys, G.H. and Eden, R.A. 1967. Geology of the country around Chesterfield, Matlock, and Mansfield. Memoir of the Geological Survey of Great Britain. England and Wales Sheet 112.

- Sognnes, K., 2001. Nye Funn: Verdens største skiløper(?). SPOR 2:32, 47.

- Sognnes, K., 2017. The Northern Rock-art Tradition in Central Norway. Oxford: BAR International Series 2837.

- Tilley, C., 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg.

- Valdez-Tullett, J., 2019. Design and connectivity: The case of Atlantic rock art, British Archaeological Report, International Series 2932, Oxford: BAR.

- Valdez-Tullett, J., Barnett, T., Robin, G., & Jeffrey, S., 2023. Revealing the Earliest Animal Engravings in Scotland: The Dunchraigaig Deer, Kilmartin. Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 2023:33(2), 281-307.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ British Isles Prehistory Archive

→ British Isles Introduction

→ Stonehenge

→ Avebury

→ Kilmartin Valley

→ The Rock Art of Northumberland

→ Rock Art on the Gower Peninsula

→ New rock art discoveries in the Peak District National Park

→ Painting the Past

→ Church Hole - Creswell Crags

→ Signalling and Performance

→ Cups and Cairns

→ Ynys Môn, North Wales

→ Bryn Celli Ddu

→ Remembering Stan Beckensall

→ The Prehistory of the Mendip Hills

→ The Red Lady of Paviland

→ Megaliths of the British Isles

→ Stone Age Mammoth Abattoir

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network