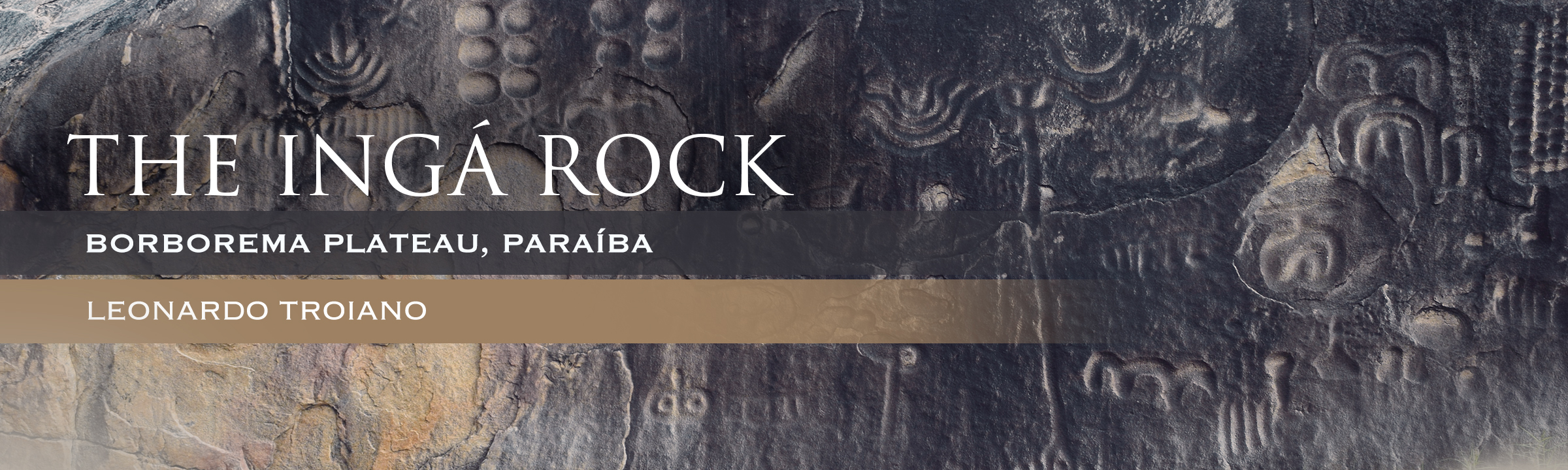

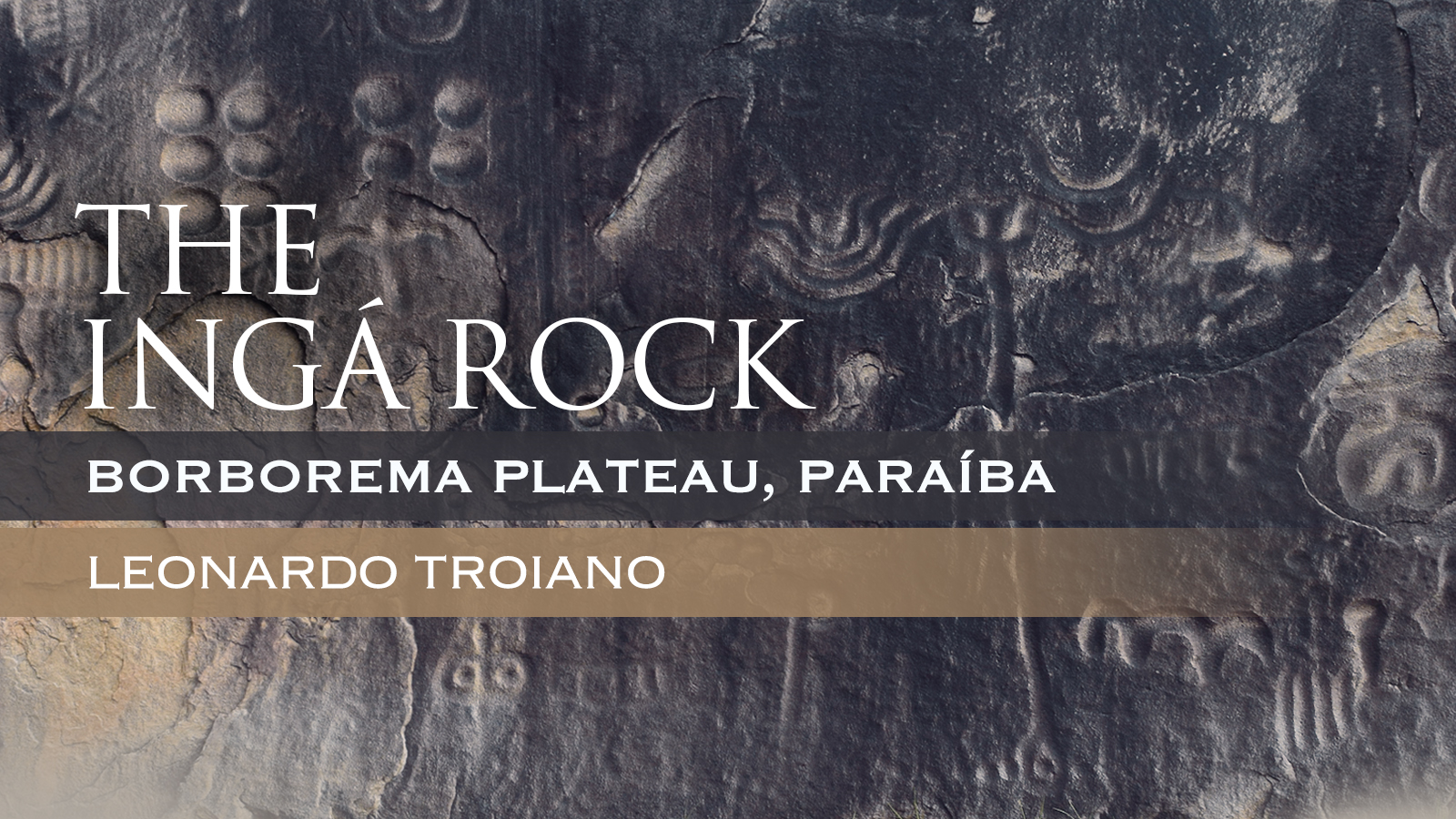

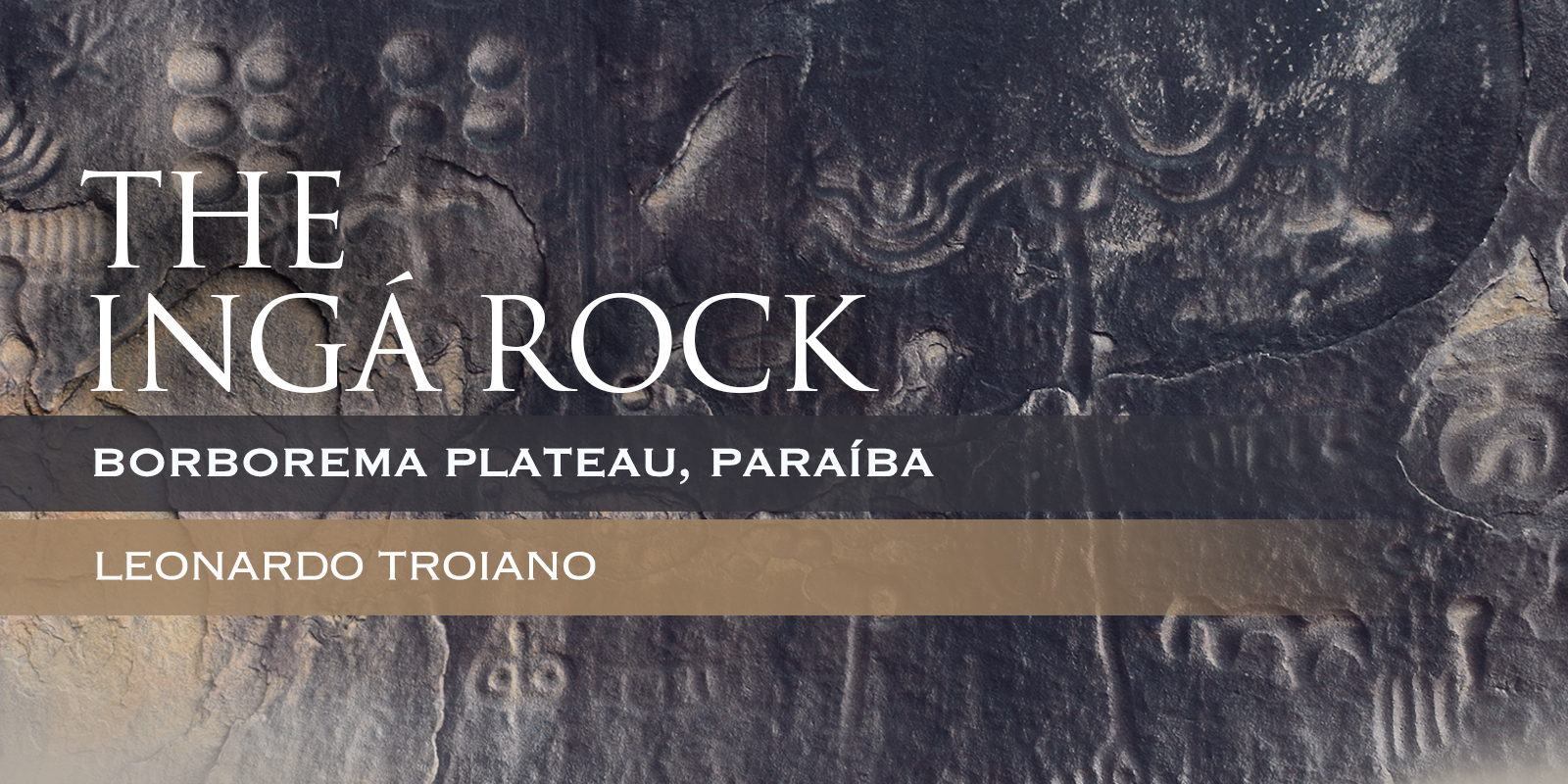

Located on the foot of the Borborema Plateau, Paraíba, near the town of Ingá, the Ingá Rock, or Ingá Itacoatiaras, is Brazil’s most famous petroglyph panel and the first archaeological monument to be officially protected by the National Heritage Service in 1944. The central panel, carved into a massive biotite-granodiorite boulder roughly 25 meters long and 3 meters high, forms part of a larger 250 m² outcrop along the Ingá River. Its surface is densely engraved with smooth, polished spirals, concentric circles, and rectilinear patterns, mostly abstract but some figurative.

Until the 1940s, the great boulder was quarried and even blasted, partly by treasure hunters who believed the engravings marked a hidden trove, and partly by the locals for cobblestone production. Such terrorist attacks against Indigenous archaeological heritage are, unfortunately, not uncommon. These destructive activities prompted the National Heritage Service to declare the site a national monument under emergency conditions. On November 30, 1944, the Ingá Rock became the first archaeological monument to receive official protection in Brazil—after 444 years of colonial rule that had denied any prestige to pre-European Indigenous presence—and long before the 1961 Law 3.924, which formally established federal safeguards for archaeological heritage.

Source: Leonardo Troiano / Bradshaw Foundation

Source: Leonardo Troiano / Bradshaw Foundation

The term Itacoatiaras became synonymous with this large, polished, smooth, and curvilineous type of petroglyph, better known from the Ingá Rock, but also found at other sites along the Ingá River (Sítio do Bravo, Pedra do Altar, Casa de Pedra, Itacoatiara do Estreito, Itacoatiara dos Macacos, Furnas do Amaragi). The word originates from Tupi, combining itá (“stone” or “rock”) and kûatiara (“scratched” or “painted”). According to oral tradition, when European colonizers inquired about the enigmatic markings carved into the rock, the Kariri and Potiguara peoples replied with a single word: itacoatiara. The term, in turn, derives from the Tupi language family, to which Potiguara belongs, combining itá (“stone”) and kûatiara (“scratched” or “painted”).

Among the many cupules that punctuate the surface, several figures stand out: some appear anthropomorphic, others evoke vegetal or branching forms, and many remain beyond interpretation. Over the decades, the engravings have inspired a wide range of speculative readings, yet none has achieved scholarly consensus. Archaeoastronomical interpretations are among the most frequent, suggesting that the motifs represent constellations, celestial movements, or calendars; however, these remain conjectural and lack empirical support. What can be said with confidence is that the panel’s visual coherence and technical refinement reveal a deliberate symbolic order, carried out through a meticulous chaîne opératoire involving compositional planning, pecking, grinding, and polishing with sand and water. The result is a monumental ensemble of petroglyphs whose meaning is obscured by time, yet still resonates through the beauty of its design.

Recent archaeometric investigations have explored whether the Itacoatiara petroglyphs were once painted. Microscopic analysis, X-ray fluorescence (XRF), and image enhancement with DStretch filters revealed faint reddish residues in some grooves, suggesting the possibility of pigment use subsequently eroded by centuries of water abrasion. Confirmed examples of engraved-and-painted panels in nearby shelters strengthen this hypothesis, offering a new dimension to the site’s aesthetic and ritual significance.

Further afield, a series of so-called marginal inscriptions spreads across the outcrop and the riverbed. Rough and irregular, many consist of little more than shallow scratches on the stone. Their style recalls the Letreiro petroglyphs found in western Paraíba, a region with an entirely different landscape and cultural background. Such variations suggest that various ethnic groups may have passed along the Ingá River over the centuries, leaving their own traces alongside those of others.

In the eight decades since the site was declared a national monument, the Brazilian State has failed to implement even the most basic protective measures. Even the protective fence intended to shield the panel from visitors and vandals was poorly conceived: its metal poles, anchored in rough concrete bases, rest directly on the petroglyph-bearing surface. No adequate system has ever been built to divert the seasonal floods that regularly submerge the entire boulder, stripping away portions of the engraved surface year after year.

The rock’s mineral composition, predominantly quartz, feldspar, and biotite, makes it both exceptionally hard and acutely vulnerable to alternating cycles of cold submersion and heat, which cause physical and thermal stress on the rock art through expansion and contraction according to temperature fluctuations. Flooding has led to flaking and exfoliation, while biological colonization, vegetation growth, and residues from past mold growth have further compromised the panel's structural integrity, which is now peeling off.

The more recent conservation studies consistently emphasize the interplay of hydric and thermal dynamics as the principal mechanism of degradation, which not so slowly threatens one of the most iconic works of Indigenous art in the Americas.

Sadly so, interpretation of the Ingá Rock has long been mired in speculation, making it one of the world’s most notorious centers of pseudoarchaeology. Over the decades, the site has attracted a procession of mystics, fringe theorists, self-styled experts, and opportunists who refuse to credit its extraordinary petroglyphs to their real Indigenous creators. Instead, they attribute them to lost civilizations such as Atlantis or, as one particularly inspired local put it, to “extraterrestrial peoples,” as if the issue were one of interplanetary ethnography.

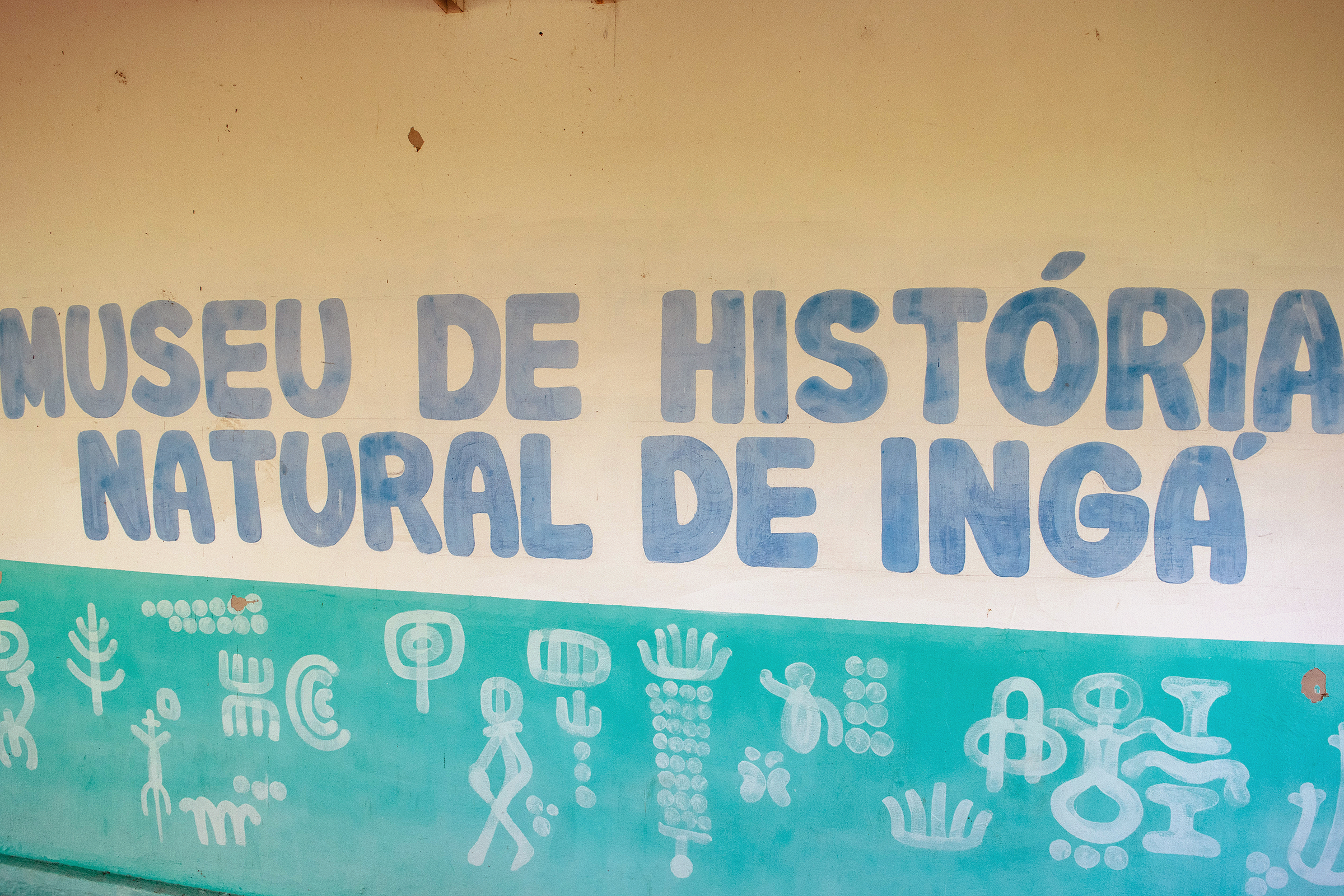

This distortion is not merely anecdotal, it is a textbook case of what happens when the State fails to ensure the scientific investigation and proper management of its archaeological heritage. In the vacuum left by public institutions, pseudoscience and racialized fantasies flourish unchecked. The small local museum, housed in a deteriorating building beside the site, offers a horrific illustration of this neglect. Its displays present visitors with a series of “hypotheses”: the “Ancient Astronaut” Hypothesis, the “Ancient Greek Sailors” Hypothesis, and an “Aboriginal Hypothesis”, before mentioning, almost as an afterthought, that Native Brazilians could have made the petroglyphs.

This situation cannot be understood apart from the historical structures that shaped Brazil’s Northeast. For much of its history, the region’s interior remained beyond the effective reach of the State, governed instead by the paternalistic hierarchies of “coronelismo”. This is a system of local domination in which powerful landowners, the “coronéis”, exercised near-feudal control through personal authority, violence, patronage, and coercion. This oligarchic order left little space for public education, cultural policy, or scientific institutions.

The Ingá Rock illustrates, perhaps more vividly than any policy document could, the consequences of structural neglect. It is a Native masterpiece, undeniably a heritage of all humankind, left largely unstudied for decades, partly dynamited, and its meaning obscured by speculation and pseudoarchaeology in a region where scientific institutions have yet to take root. One can only imagine what the Ingá itacoatiaras looked like in their prime, likely painted in vivid iron-based reds and still intact, when generations of Indigenous caretakers, long before the colonial era, tended to them with reverence and awe.

The Ingá Rock still lacks a coherent preservation and interpretation strategy. Its future depends not on another isolated intervention, but on a sustained, integrated program that accords the site the care and attention it deserves.

The first step is to control the forces that are slowly eroding it. A hydrothermal management plan must finally be implemented, one that respects the rock’s natural character while protecting it from destruction. Small micro-drains and flow deflectors, designed to redirect the torrent without touching the engraved surface, could mitigate flooding-related damage. At the same time, reversible shading structures would soften the extreme thermal amplitudes that slowly but surely crack the monument.

Preservation must become routine. The site should no longer depend on sporadic rescue campaigns but on a continuous cycle of care: periodic biological cleaning, vegetation control, and consolidations only during dry periods, combined with annual 3D and photometric monitoring to record the rock’s subtle transformations.

Alongside conservation, the site calls for research that matches its complexity, rather than the pseudoscientific documentaries that too often take its place. Regrettably, such productions tend to receive greater funding than the site’s own management and conservation budget. The museum’s exhibition and interpretation program must be rewritten from scratch. The Ingá River is also a rich Pleistocene paleontological site, with giant sloths, armadillos, South American elephants, toxodontia, and many more, and the museum should house a proper mount of the magnificent species that once roamed the area. The current confusion of pseudoarchaeological speculation must be extirpated for good, giving way to a narrative that restores Indigenous dignity, authorship, and agency, and situates the site within its ritual and environmental context. This reinterpretation should do more than inform visitors. It should make them think about how such myths of “ancient aliens” and “lost civilizations” not only don’t expand history but erase it, recycling the same 19th-century racist nonsense under a shinier name.

A qualified archaeotourism program is undoubtedly vital, with trained guides, clear bilingual signage, and integration into regional cultural routes. A sense of appreciation for the site’s truly beautiful flora, which is a blend of semi-arid caatinga and remnants of Atlantic forest, should not be overlooked. A thoughtful landscape program would greatly enhance and protect the area surrounding the site, creating a gravitational pull for tourists interested in both nature and culture. After all, the site is only 100km from the state’s capital, João Pessoa, a tropical beach paradise already very popular.

There is no masking reality. Brazil is a country of sharp contrasts, where economic inequality finds its mirror in the unequal treatment of cultural and, above all, archaeological heritage. The Ingá Rock has been listed on Brazil’s UNESCO Tentative List for nearly a decade (since 2015), as “The Ingá River Itacoatiaras”. Yet every appeal for proper infrastructure, befitting a site of potential World Heritage status, has gone unanswered, leaving its care in the hands of local staff with no formal training or qualifications. The State, it seems, listed the Itacoatiaras as a national monument almost a century ago and, since then, has responded with a silent shrug. “Cry me a river, Ingá”. Year after year, the Ministry of Culture continues to devote a wildly disproportionate share of its resources to colonial architecture, while pre-colonial, Indigenous archaeological sites, especially those as delicate as rock art, remain excluded from any serious investment or care. The country still seems to seek validation from abroad, often trying to attach its image to Europe through colonial heritage, always searching for an identity that has been here all along—in plain sight, quite literally, written in the walls.

- Brito, V. (2009). A pedra do Ingá: Itacoatiaras na Paraíba. Editora da Universidade Federal de Campina Grande.

- Borges, L. E., dos Santos, C. A., Oliveira, F. M., & Lage, M. D. C. S. (2016). Estudo petrográfico do suporte rochoso do sítio arqueológico da Pedra do Ingá, PB. Geonomos.

- Catoira, T., & Azevedi Netto, C. X. (2018). Itacoatiaras do Ingá: As diferentes “escritas” no imaginário da pedra das águas. Revista Anthropológicas, 29(1), 57–83.

- Nascimento, A. L. M. L., & Lima, T. A. (2018). As itacoatiaras do Ingá: Gravuras pintadas? The itacoatiaras of Ingá: Painted carvings? Clio Arqueológica, 33(1), 26–45. https://doi.org/10.20891/clio.v33n1p26-45

- Troiano, L., & Haertel, L. M. (2025). O mar não esperará: a corrida do Brasil para salvar ou sacrificar seu patrimônio cultural. Tempo Exterior, 26 (50), 56-72.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ Brazil Rock Art Archive

→ The Lajedo de Soledade

→ The Rock Art of Pedra Grande

→ the Rock Art of Serrote do Letreiro

→ The Ingá Rock

→ The Peruaçu National Park

→ The Poty River Canyon Petroglyphs

→ Rock Art of Serra da Capivara

→ Rock Art of Pedra Furada

→ The Rock Art of Santa Catarina

→ South America Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network