Paul S. C. Taçon, Suzanne Thompson, Kate Greenwood, Andrea Jalandoni , Michael Williams & Maria Kottermair

Map showing the location of Turraburra and neighbouring Grey Rock.

Orthomosaic of Marra Wonga (Gracevale rock art site) created from drone images with yellow line 162 metres in length (straight distance 158 metres) delineating the extent of the rock art panel.

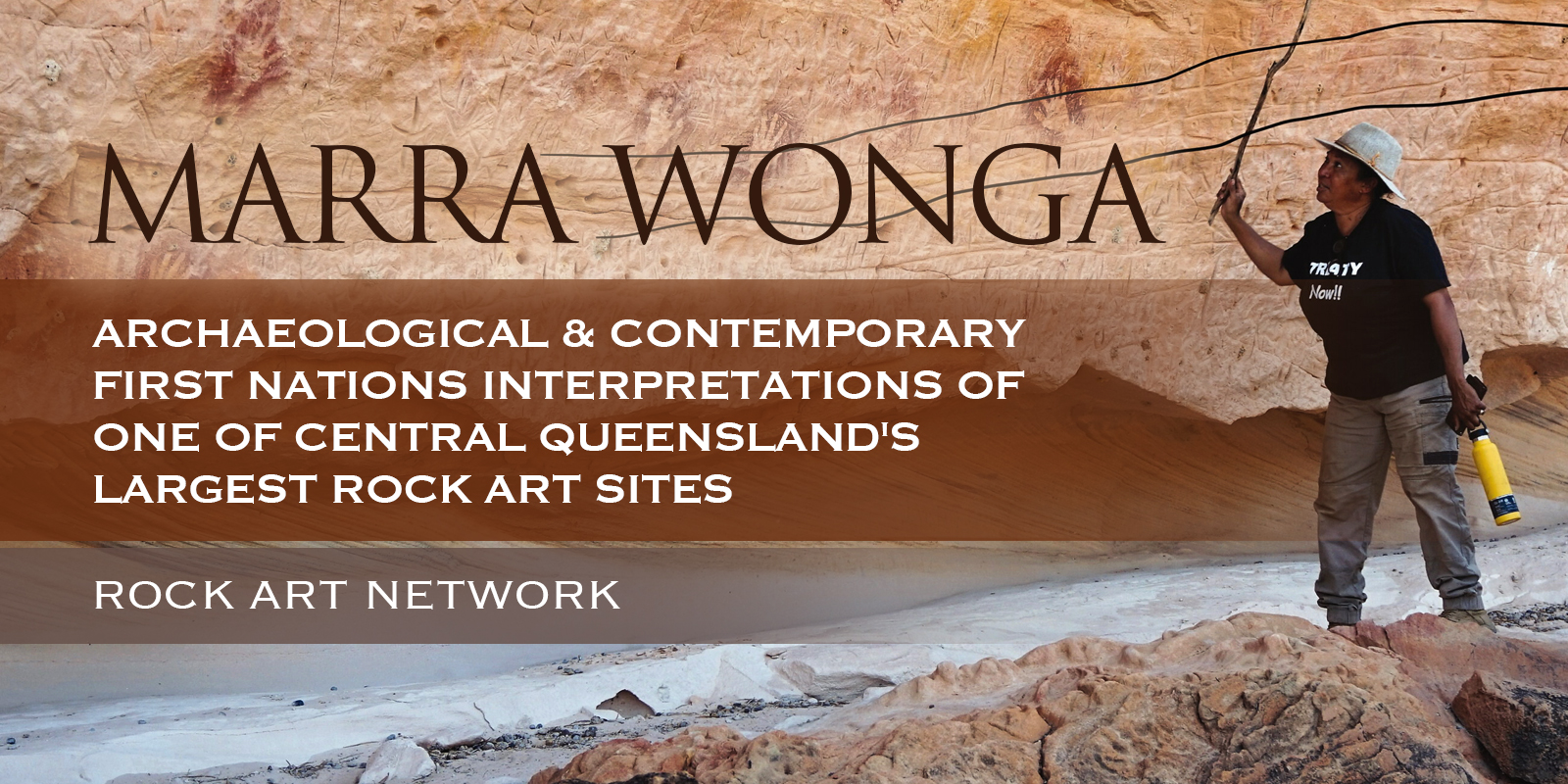

Marra Wonga is a growing Aboriginal-led tourism destination, so aspects of the history of Marra Wonga tourist visitation are also reviewed. Marra Wonga is interpreted by contemporary Aboriginal community members as a major teaching site, therefore the question of whether Marra Wonga has the features of a teaching or aggregation site that would have been of importance to a range of Aboriginal groups prior to colonisation is also briefly explored, something worthy of in-depth study in the future.

According to McCarthy (1960:403), the site was known locally as ‘The Art Gallery’ in the 1950s. Gunn (2000:35) stated that there was no known Aboriginal name for the main Gracevale rock art site but suggested the name change from ‘Gracevale Aboriginal rock art site’ to something, such as ‘Iningai Aboriginal rock art shelter on Gracevale’. Today the site is known as ‘Marra Wonga’, which means ‘place of many stories’ in the Iningai language.

The central portion of Marra Wonga with an extensive wall of petroglyphs and stencils.

Turraburra is about 52 kilometres east of Aramac and 890 kilometres northwest of Brisbane. It is 387 metres above sea level and has been primarily used for sheep and/or cattle grazing since the late 1800s. The station is located in traditional Iningai territory (Tindale 1974:169) and according to Christison, who moved to the region in 1863 (Bennett 1927:399), is associated with the Terraburra clan (see 1884 map in Smith 1994:16), one of the reasons Gracevale was renamed and officially launched as ‘Turraburra’ on 1 October 2020.

The bioregion where Turraburra is located consists of Desert Uplands (Smith and Rowland 1991). Land zones include Tertiary—early Quaternary loamy, sandy plains and plateaus, Cainozoic duricrusts and sandstone ranges (Wilson and Taylor 2012). Soils are very deep sandy red and yellow earths, minor grey clays and siliceous sands (Wilson and Taylor 2012). The Desert Uplands bioregion is dominated by eucalypt woodland with an understorey of spinifex (Stanton and Morgan 1977). Rainfall occurs mostly in the summer, increasing during cyclones, which also occur in the summer months (Smith and Rowland 1991) and there are a number of springs, soaks and ‘native wells’ on the property, some close to the site. The site environment is open woodland of lancewood, wattle, mulga and ironbark with an understorey of spinifex (Franklin 1998:3).

The earliest non-Indigenous documentation of the Iningai People is from Thomas Mitchell when he explored central Queensland in 1846 (Hoch 1986:14). Mitchell noted substantially constructed lean-to huts with bark tiles on the roof (Hoch 1986:14) as well as large permanent huts of a ‘very numerous tribe’ and well beaten paths (Hoch 1986:14; Smith 1994:15). Mitchell tried to avoid the local Aboriginal people, but he encountered a big group digging for mussels in a lagoon (Hoch 1986:14). ‘His party was greeted by loud shrieks of women and children and by angry shouts of the men who called “Aya minya” taken to mean “What do you want?” ’ (Hoch 1986:14). Mitchell described a long-handled iron tomahawk in the hands of ‘a Chief’ but Mitchell came to no harm (Hoch 1986:14).

Christison explored the region for a suitable pastoral property from 1863 to 1866 and was the first European to establish cordial relations with the Dalleburra/Iningai people of the region. He established Lammermoor Station in Hughenden, about 200 kilometres northwest of Turraburra, in the 1860s, employed Dalleburra people and documented their culture (Clarke 2013:53; Smith 1994:15). Christison allowed Aboriginal people to camp on his station for the 30 years he occupied the area and, thus, acquired a great deal of knowledge about the First Australians of the region. Christison created a map, which shows the Dalleburra language group covering the area north of Hughenden to south of Aramac, including the area where Turraburra is today. The Dalleburra/Iningai language is closely related to the neighbouring language of Bidjara to the east, as well as sharing some words with Wadjabangayi and Dharawala to the west and south (State Library of Queensland 2020).

Christison estimated that there were 500 Dalleburra people throughout their Country (Bennett 1927:402) and other estimates included that a group on the Alice River was around 700 people at the time of colonisation (Hoch 1986:14). The Iningai ‘… were said to be a superior people, some over six feet tall and with a life span of ninety years’ (Hoch 1986:14). Customary tribal scars denoted the Iningai people and in some areas, people knocked out a front tooth in male initiations (Porter 1961:51).

In 1877, the Greyrock Hotel license was granted at neighbouring Gray Rock station (Gunn 2000:11; Norris 1996) and in 1882 George Porter licensed land where Turraburra is located as Charlie’s Creek No. 5 (Cooper 2013:9, Figure 49). The Porter family were the first non-Indigenous people to settle in this area but there is no mention of rock art in George’s son’s memoirs (Porter 1961). In the memoirs there is frequent mention of the local Aboriginal people but, as in many parts of Queensland, Iningai were subject to massacres and relocation to missions in later years (Hoch 1986). However, there were some Iningai people who survived the massacres and who were not living on the stations, with an Aboriginal group camped at Lake Dolly, 10 km east of Barcaldine being recorded (Hoch 1986:40). These people earned some rations by doing odd jobs, such as cutting wood (Hoch 1986:40). By 1902, only 37 Iningai adults and 3 children were recorded in the area (Hoch 1986:49).

The Turraburra property, under three former names, has been leased or owned by many people since 1882. In 1888, the property became part of Boongoondoo, which meant ‘The Big Water’ in the local Aboriginal dialect of the time (Porter 1961:77). After being leased or owned by 17 different non-Aboriginal individuals or families between 1882 and 2019 (Taçon et al. 2020a), the station was most recently purchased by the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation and leased to YACHATDAC on 19 April 2019. The property is currently being developed for heritage preservation, cultural tourism, conservation, and other purposes.

The earliest current evidence of people in the central Queensland highlands is from Kenniff Cave and dates to about 19,000 years ago (Morwood 2002:208–209; Mulvaney and Joyce 1965). In terms of rock art, Morwood (2002:218) identifies three phases. In the first, Central Queensland Phase 1, rock art is estimated to be over 5,000 years old and consists of pecked rock engravings: ‘Deeply pecked engravings pecked into case-hardened surfaces of tracks, arcs, circles, lines and pits. These motifs were incorporated into complex patterns, such as compositions of circles, arcs, lines and tracks’ (Morwood 2002:218).

Central Queensland Phase 2 rock art is argued to have been made between <5,000 years ago to 36 BP and consists of recent pecked and abraded engravings and red paintings (including stencils): ‘Most surviving rock art in the region is from this phase. Techniques included stencilling, imprinting, painting, pecking, abrasion and prebrasion. The full range of colours was also used. The range of engraved motifs is significantly different from that of Phase 1, especially in the addition of the human vulva motif’ (Morwood 2002:219).

Central Queensland Phase 3 rock art was made between 140 to 36 BP and is ‘characterized by increased emphasis on the use of white and the depiction of grids. A number of distinctive motifs and compositions also appear, especially lizards, tortoises and lizard/grid compositions’ (Morwood 2002:220).

There are a wide variety of Aboriginal cultural heritage sites across Iningai Country. State registered sites include native wells, artefact scatters, stone arrangements, engraved and painted art sites, scarred and carved trees, a midden, contact sites, quarries, hearths, ovens and story places. Although bora rings were noted by stockmen (Cooper 2013:9), none is registered. Within 40 km of Turraburra there are nine cultural heritage sites with 17 site components registered. Rock art sites make up eight of the 17 site components (47.06%).

The earliest published reference to Iningai rock art is in a 21 June 1900 letter to the editor of a journal called Science of Man: ‘Hereabouts the tribal districts are quite distinctly safeguarded, and the name of each tribe ends with ‘burra’, as Mootaburra, Queefeen-burra, Bowlaburra, Mungooburra, and Dalleburra, etc. … The ochre handmarks are numerous in the sandstone rocks and in the caves some thirty miles from here’ (Anonymous 1900:82). However, it is unknown which sites were referred to or whether the author visited Marra Wonga.

In 1958, Gavin Vance photographed Marra Wonga and sent photographs to Australian Museum-based archaeologist Fred McCarthy (McCarthy 1960:400). In 1960, McCarthy published the first, although brief, account of Marra Wonga with Vance’s photographs but did not visit the site. The first recording of Marra Wonga was undertaken in 1976 by Pratt (1976a, 1976b), a ranger, and consisted of a paper archaeological Site Index Form (Pratt 1976b), a Relics Report Form (Pratt 1976a) and ‘A full roll of film’ (Pratt 1976a:2), the latter important for rock art deterioration studies. However, the site was not included in Morwood’s PhD archaeological study of Central Queensland rock art that commenced the same year and led to 17,025 motifs recorded at 84 rock shelters (see Morwood 1979, 2002:212). Consultant archaeologist Robert Neal visited the site on 9 January 1987. ‘He was directed to the site from some 300 km away, such is the extent of local knowledge about Gracevale. Information received from Neal indicated that at the time, the site was being visited by travellers, who found out about the site by word of mouth. No formal guided tours were being run at the time of recording’ (Franklin 1998:5). Neal did not fill out site recording forms but took some photo mosaics.

In 1996, the owners of the then Gracevale Station opened the rock art site to tourists (Cooper 2013:9). An article about Marra Wonga featuring Frank Dancey was published in the Courier Mail on 28 September, 1996 (see Peterson 1996). It refers to the first tourists and Tom Lochie’s Artesian Country Tours, as well as that there was a move to make the site a protected part of the Register of the National Estate. According to Franklin (1998:1), Lochie’s tours commenced in May 1996; in addition, there were informal tours conducted by the property owners, Chris, Jill, Michael and Leigh Dyer. Over the coming years, Lochie installed toilets and picnic facilities immediately south of the main rock art site.

Franklin (1998, 2003:50–51) visited the site and wrote the first management report for Marra Wonga, prompted by ‘A perceived need for fencing at Gracevale Rock Art Site’ (Franklin 2003:50). Franklin mentioned Lochie had taken 1060 people to Gracevale; tours are on demand and ‘primarily attract retirees but he has also takes (sic) school children’ (1998:9). Following Franklin, Gunn (2000) was contracted to write a management and interpretation report on Marra Wonga as well as the Gray Rock Historical Reserve. Lockie’s tours to Marra Wonga ceased in 2017 and he passed away in January 2018 (Gall 2018).

Academic interest in Marra Wonga took off in 2019 after a conference paper on Marra Wonga rock art was presented at the Australian Archaeological Association Inc. Annual Conference that year (Prideaux et al. 2019) and a journal article (Brown and Thompson 2020) was published.

Marra Wonga was documented over several days in September 2020 and June/July 2021 but other rock art sites at Turraburra and neighbouring properties were also briefly visited and recorded (see below), primarily with photography and note-taking, as well as some photogrammetry. GPS coordinates were obtained and the size of rock shelters was measured. Stone artefact scatters were also observed and photographed, along with native wells.

State-of-the-art methods for rock art documentation were applied at Turraburra, which included aerial and terrestrial photogrammetry, laser scanning, and gigapixel panoramas. The deliverables were high-resolution panoramas, accurate and photo-realistic 3 D models, and orthomosaics (Jalandoni 2021).

The open conditions at the main panel of Marra Wonga made it suitable for a gigapixel panorama. The high-resolution panorama was created by capturing images using a Gigapan Epic Pro, Canon 6D mark ii, and fixed 100 mm lens. The images were stitched using Adobe Photoshop to produce the gigapixel image that enables viewers to see the whole panel in one image and still zoom in to see details. (see https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/4486).

A portion of Marra Wonga with hundreds of petroglyphs including lots of macropod tracks.

The exact number of rock markings is as yet not known, but the total number is not essential for the purposes of this paper. However, there are at least 15,000 petroglyphs (rock engravings, incisings, pecked designs, drilled motifs, and images made by pounding the rock surface), calculated by noting the area marked with rock art on the wall is 160 metres long by an average of 1.8 metres high (288 square metres) and that, although the number of petrogylphs per square metre varies, across much of the shelter wall there are at least 50 or more petroglyphs per square metre, and there are also a few hundred petroglyphs on boulders, small ceiling areas, and parts of the shelter floor.

There are both natural and drilled holes at the site across the rear wall, including some holes drilled into incised lines. There are pecked designs over/cut into pounded tracks. A wide range of bird and land animal tracks can be discerned, including macropod tracks of various shapes and sizes (Figure 4), a few possum-like tracks, and a solitary dingo track.

A photograph (A) and digitally manipulated image (B) of the Marra Wonga anthropomorph, enhanced using 3D modelling and Topographic Position Index following the method in Jalandoni and Kottermair (2018). The anthropomorph (at the southern end of the site) is interpreted by Aboriginal community members as Ancestral Being Wattanuri.

A few metres to the right of the anthropomorph is a snake-like design 2.28 metres in length and up to 28.8 cm high (Figure 6). The outline of its body consists of long lines filled with drilled holes. The right end disappears into a rock crevice formed by a piece of overhanging wall that juts out. The body is bulbous in the middle and each end tapers. It cuts through and is surrounded by numerous bird tracks and some other designs, including some small sets of paired boomerang-like petroglyphs.

There are a few engraved feet on the shelter wall and a boulder but the main concentration is on the remains of a case-hardened sandstone rock platform towards the southern end of the shelter, which abuts part of the wall (Figure 7). There are 19 human-like footprints, including two large ones with six toes that are heel to heel immediately below the wall (Figure 8). Next to them are engraved feet with six, four and 11 toes. Of the 19 feet, eleven have five toes, six have six toes, one has four toes and one has 11 toes (Table 1). The foot with eleven toes measures 23.4 cm by 48.2 cm, while the two largest feet, with six toes engraved heel to heel, take up a space that is 29.8 cm by 1.17 metre. On the platform to the right (north) of the feet are three bird tracks, a set of three lines, two arcs and a small, abraded edge area. The platform measures 1.51 metres (east-west) by 2.77 metres (north-south).

The seven star-like design cluster enhanced with DStretch and with star design locations indicated with numbers.

A very distinctive engraved ‘penis’ is a few metres north of the platform of feet, high on the wall where a short projection of rock forms a sideways L-shape that frames it (Figure 10). The phallus petroglyph is 24.6 cm high by 16.5 cm wide, not including a red ochre outline added sometime after the completion of this petroglyph, which now frames and highlights it. It is next to a large purple adult open hand stencil to its immediate right and there is a red adult hand stencil a bit further to the right and below. Seven small, engraved boomerangs depicted as if in flight lead from the ‘penis’ to an area to the immediate right with the seven star-like petroglyphs.

The eighth star-like design at Marra Wonga near the northern end of the rock art panel just above the floor. It has been interpreted as a Seven Sister representation on Earth.

While recording Marra Wonga on 11 September 2020, MW and PT found an eighth star-like design (Figure 13) at the far right (northern) end of the site just above the rock floor. It is only about 3 m from the end of the rock art panel and measures 23.2 cm high by 28.5 cm wide. It is hidden, and was not noticed before, while the seven stars on the central part of the wall panel were meant to be seen, even from some distance. The eighth star also faces a different direction from the other stars and most of the rest of Marra Wonga’s rock art—northwest at 310° instead of east.

A long snake design (Figure 14) begins with what appears to be its pointed tail where the seven stars end and continues for over 11 m north along the wall panel (head to tail = 11.22 metres). It varies in width from a point at the south end (tail) to 4.4 cm at the north end (head) and to 48.3 cm in the middle. It is composed of a range of different linear designs within the long lines that form its shape.

In terms of stencils, there are 100 hand-related stencils, including some child-size (<7 × 7 cm), and 11 object stencils. As can be seen in Table 2, the hand-related stencils consist of 57 adult left hand stencils, 16 adult right hand stencils, five partial adult hand stencils, 12 adult left hand-and-wrist stencils, three adult right hand-and-wrist stencils, one adult left hand-and-arm stencil, one adult fist stencil, and five child hand stencils (three left, two right). Fifty-nine percent of hand-related stencils are red, 22% purple, 10% white, and 9% yellow. Seventy-four percent of hand-related stencils are of the left hand but of the nine yellow hand stencils, five are right hands. In a natural oval depression, there are red stencils under yellow ones, which in turn are underneath a white stencil. Elsewhere, there are purple hand stencils under red or yellow hand stencils so the sequence is purple, red, yellow followed by white. Most stencils are over engravings but some recent engraved designs were cut into stencils.

| Table 2. Hand related stencils by type and colour at Marra Wonga. | |||||

| Type/colour | Red | Purple | White | Yellow | Total |

| Adult left hand | 30 | 14 | 9 | 4 | 57 |

| Adult right hand | 9 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 16 |

| Adult partial hand | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Adult left hand-and wrist | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Adult right hand-and-wrist | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Adult left hand-and-arm | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Adult left fist | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Child left hand | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Child right hand | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 59 | 22 | 10 | 9 | 100 |

Suzanne Thompson in front of the engraved snake-like design, interpreted as a ‘Rainbow Serpent’ depiction (with black line showing its position). Thompson is explaining the significance of the rock art.

The two long red boomerang stencils are 86.1 cm in length and located in a small ceiling area of a concavity in the wall. This is the only paired set of boomerang stencils at Marra Wonga or at other sites in the vicinity. To their immediate right is a rare red fist stencil (Figure 15). A bit further along, where the wall surface changes, there are red hand stencils. Just north of the red boomerang and hand stencils is a stencil of a digging stick that is 81 cm long on another wall cavity ceiling. There is a yellow boomerang stencil below it. Digging stick stencils are very rare across Australia in comparison to boomerang and other object stencils (e.g. for central Queensland see Morwood 1979: Table 8:9a, between pages 313 and 314, where he recorded 142 boomerang stencils but no digging stick stencils). On an adjacent but broken ceiling panel are the remains of at least five stencils of digging stick tips. It appears they may have been complete or at least longer stencils before part of the rock crumbled and broke off. In the vicinity is the circular stencil that looks as if it is of a woman’s ring pad. Object stencils are not found at any other Turraburra rock art sites or at sites on neighbouring properties.

Two red boomerang stencils and a red fist stencil on the ceiling of a low wall concavity.

In many parts of Marra Wonga, natural features on the rear wall panel, such as cavities, oval depressions, holes, cracks and changes in orientation, have been utilised for the placement of petroglyphs, clusters of hand-related stencils, and all of the object stencils.

There is some graffiti carved on the wall at various locations. Most consists of names and initials, including ‘N. MELVILLE’ above ‘TMcK’, ‘H. HALLAM’ and ‘PEARL’. In 1913, T. Smith left his name and date in a small rock art shelter a few hundred metres south of Marra Wonga. This is the oldest dated graffiti at Turraburra and is still visible.

Marra Wonga has a large scatter of stone artefacts nearby but no artefacts next to the rock art panel, although artefacts once near the rock art could have been removed by station owners and visitors, including tourists, since the late 1800s, as has occurred at many rock art sites across Australia. ‘The main scatter begins roughly 120 metres southeast of this site. This suggests people camped a short distance away, entering the rock shelter for separate (artistic and/or ceremonial) activities’ (Wright 2022:7). Five other artefact scatters were recorded elsewhere at Turraburra in 2022 (Wright 2022:4).

All documented rock art sites in the vicinity of Marra Wonga are substantially smaller both in size and number of motifs. In 2020, we documented a white pigment quarry site and 14 rock art sites consisting of petroglyphs or petroglyphs and hand-related stencils similar to those of Marra Wonga. One notable difference is that one site a few hundred metres south of Marra Wonga has a black adult left hand stencil. At another small site, just over 15 metres in length, there are engraved bird tracks and seven star-like designs, in clusters of three and four. At Gray Rock station, 11 km west of Turraburra, there is a small site with a yellow human adult foot stencil over a white adult hand stencil, as well as yellow adult hand stencils over a red adult hand stencil and two red child hand stencils.

At the Gray Rock Historical Reserve, which is well known for being the site of the Greyrock Hotel established in 1877 and for its historic graffiti, there are four anthropomorph petroglyphs similar in style to the one at the southern end of Marra Wonga, also with fully carved bodies. Three of the anthropomorphs are located amongst the engraved names and dates of various ages at the southern end of the sandstone wall, near the top and about 4 m above ground. A large anthropomorph just over 60 cm high was arranged with two small anthropomorphs 16 cm high on either side of it. All have long penises. The fourth anthropomorph petroglyph, about 67 cm high, is on a small rock platform below the eastern side of the rock complex.

On the southern wall there are also two engraved human-like feet and an engraved possum-like clawed hand. Engraved human figures are rare in the rock art of the central Queensland highlands. Given that the style of the figures at Gray Rock is the same as the anthropomorph at Marra Wonga, they were probably made by the same individual or group working at both sites, in order to connect the two places in some way, for instance, as part of a Dreaming Track or Songline.

Nine additional small rock art sites were recorded by others at Turraburra in 2021 (Wright 2022:20–24). Eight have fewer than ten petroglyphs and no stencils. One site with about 20 petroglyphs has four small star-like designs (Wright 2022:23).

Morwood (1979) recorded 90 rock art sites in the Central Queensland Highlands but only nine have star designs, with 31 such motifs in total (Table 3). Twenty-five are abraded star designs from seven sites (13 at Black’s Palace 1, one at Black’s Palace 2, two at Black’s Palace 4, four at Black’s Palace 5, one at Goat Rock, two at Ochre Site 1 and two at Paddy’s Cave) out of 10,634 abraded motifs (Morwood 1979: Table 9.4). There are also six pecked star designs from two sites (one at Plateau Site 3 and five at Morven Site) out of 1850 pecked motifs (1979:Table 9.5).

(Morwood 1979)

(Morwood 1979)

(Morwood 1979)

(Morwood 1979)

(Morwood 1979)

(Morwood 1979)

(Morwood 1979)

(Morwood 1979)

(Morwood 1979)

The rock art of Marra Wonga has not been scientifically dated, although there is some potential for obtaining minimum ages of some designs that have fossilised mudwasp nests over them. As Gunn (2000:35) noted, ‘The pecked motifs tend to be on horizontal case-hardened panels and ledges and on the floor of the shelter. The abraded motifs are on the friable (soft), vertical sections of the rear wall and on boulders and blocks within the shelter’. These pecked motifs are likely to be over 5,000 years old and from Morwood’s (2002:218) Central Queensland Phase 1 rock art period, while pecked designs elsewhere, other petroglyphs, and the red and purple stencils would have been made during Morwood’s (2002:219) Central Queensland Phase 2 rock art period, between 5,000 BP and 36 BP. The white stencils were likely to have been made during Morwood’s Central Queensland Phase 3 rock art period, from 140 to 36 BP, as this period is ‘characterized by increased emphasis on the use of white’ (Morwood 2002:220). Yellow stencils may also have been made during this period, given that they consistently overlie red and purple stencils and are of a different character.

There are ten clusters of designs spread across the length of the engraved area of Marra Wonga that appear to have been placed in a particular order, from south to north, as if they are sequential components of an important story. This ordered placement can be revealed by an archaeological recording of the shelter but the designs were likely to have been made at different times, with an accumulation of these clusters and other rock markings over time. However, the order makes sense for contemporary Aboriginal community members as different parts of a Seven Sisters Dreaming story, in the correct sequence. Below is an interpretation based on ethnographic information from sources referred to in the Introduction and otherwise specifically indicated.

The Marra Wonga anthropomorph (Figure 5) is interpreted as Wattanuri by Iningai and other Elders. This person is a very important Ancestral Being with varying names in different languages who sometimes is associated with Orion, and for some Iningai Elders the Morning Star. The Gray Rock anthropomorphs are also interpreted as depictions of Wattanuri by Elders. It is Wattanuri who pursues the Seven Sisters in most Seven Sisters stories across Australia, usually always a Clever man, who can shape-shift into objects, vegetation (a tree) and animals, such as a snake (Greenwood and Taçon 2022).

The snake-like design (Figure 6) could show that Wattanuri has shifted from human-like form to snake-like form, as is the case in some Seven Sisters stories (e.g. Neale 2017:133; Rose 2011:55–56), although some contemporary Iningai interpretations are that it is a mythical or extinct prehistoric animal.

Elders visiting Marra Wonga suggest the feet (Figures 7 and 8) are Wattanuri’s footprints. In some Seven Sisters stories, Wattanuri is said to have gone under the Earth and later popped up in long grass. He tests his footprint in some stories and sees that his magic is out of control as the number of his toes keeps changing (Yovich et al. 2017). Thus, some of the Seven Sisters ethnographic literature supports the contemporary community’s interpretation that this location is a place or illustration of where Wattanuri tested his feet.

Iningai and other Elders stated the ‘penis’ (Figure 10) is a representation of Wattanuri. Wattanuri’s large penis features in most Seven Sisters stories (e.g. Greenwood and Taçon 2022) and in some stories he carries boomerangs as both hunter and Clever man (e.g. Greenway 1901; Greenway et al. 1878). Iningai Elders interpret the boomerang-like petroglyphs as having been thrown by Wattanuri at the Seven Sisters.

The seven star-like designs (Figures 11 and 12) are said to represent the Seven Sisters that feature in stories across Australia and are linked to the Pleiades star constellation (e.g. Mate Mate in Franklin 1998:5–6; David Thompson, contemporary Iningai and other Elders, pers. comm. 2021/22). Most of the stories are associated with the creation of Country, through the Seven Sisters who were very beautiful and came down to earth from the sky. They were chased by a (sometimes said to be evil) man with a big penis who wanted to make the sisters his wives. All of the stories involve events that happened at certain places between the man (or sometimes two men, sometimes seven) and the women who are constantly trying to get away. The places where altercations occurred are where there are particularly pronounced features in the landscape, such as hills, claypans, waterholes and, on rare occasions, rock art sites. The different stories all have morals to them. Sometimes their pursuer rapes the older sister and the other sisters have to heal her. The story then has imbedded important knowledge of which plants they used for healing (Greenwood and Taçon 2022).

The 11.22 m snake in the centre of Marra Wonga (Figure 14) has long been interpreted as a Rainbow Serpent (e.g. Franklin 1998:6; Peterson 1996) and its enormous size is certainly suggestive of this. Rainbow Serpents figure in some Seven Sisters stories. As Neale (2017:133) recounts for Ngaanyatjara Lands and the Kura Ala Songline:

The Kungkarrangkalpa (Seven Sisters) travel in a westerly direction from Pirilyilunguru to Tjukaltjara, but Wati Nyiru finds them and pursues them to Kuru Ala (meaning ‘eyes open’), a striking rock formation with two caves that look like eyes under a jutting brow. Kuru Ala is a powerful Kungkarrangkalpa site, sacred to women. It is at Kuru ala that Wati Nyiru captures and hurts the eldest sister. Kuru Ala is also a healing place, where the sisters gather medicine plants and food. Wati Nyiru hears them and transforms his phallus into a kuniya (carpet snake), which he sends down through a crack in the rocks. The women pursue and catch the snake, and throw it away. As it flies westwards towards Kulyuru, it shines with all the colours of the rainbow. At Minyma Ngampi they cook and eat the snake ‘meat’ before realising it is part of Wati Nyiru. They become dizzy and ill, vomiting up the meat before they fly up to become stars.

Contemporary Elders remarked on the powerful aesthetics of the boomerang composition (Figure 15), that the pairing could signal something exceptional and that it represents a male presence. In several Seven Sisters stories from elsewhere it is emphasised that Wattanuri carries a boomerang or boomerangs (e.g. Greenway 1901; Greenway et al. 1878).

Contemporary Elders identify the digging stick stencil (Figure 16) and the possible ring pad stencil as important women’s objects, and symbols of female presence, including the Seven Sisters. Digging sticks are highly associated with women and were used by women for a variety of purposes besides food procurement (Nugent 2006:90). In many Seven Sisters stories it is said the women carried fire at the end of their digging sticks and fire is an important aspect of the stories (e.g. Nyoongah 1994:35–36; Massola 1968:52–53). Digging sticks also feature in certain Seven Sisters stories as magic, that protect the women (Fuller 2020:160–161); in another they are used to capture the women (Sveiby and Skuthorpe 2006:117); and in an additional story, they are used to hit the men that try and grab the women (National Museum of Australia 2010:53). There is teaching about bush foods, and medicines obtained with digging sticks and by other means, in many of the Seven Sisters stories (e.g. Greenwood and Taçon 2022; Mathews 1908:203–206; Neale 2017:133; Yovich et al. 2017). In some stories, such as one from central Australia, men chasing the Seven Sisters ‘turned into a quoit-shaped object, such as women use as a base for carrying wooden dishes on their heads’ (Berndt and Berndt 1982:250).

The dingo track (Figure 9) is close to the northern end of the area of Marra Wonga marked with rock art. A lot of the Seven Sisters stories across Australia have dingoes that are looking after the women (e.g. Constable and Love 2015:40; Greenwood and Taçon 2022; Hercus 2012:84), or the dingoes are the men chasing them. Dingo stories, some of which are associated with the Seven Sisters and/or other Beings, are also prominent through central and western Queensland (e.g. Constable and Love 2015:40; Franklin et al. 2021; Rose 2011; Taçon 2008). For instance, for the nearby Bidjara ‘the white dingo story brings the story of the Seven Sisters who came from the stars and passed down the stories. The Seven Sisters were protected by two white dingos [sic] and the seven springs above Carnarvon station relate to that’ (Constable and Love 2015:40). Bidjara Elder Floyd Robinson recounted the White Dingo and Red Dingo story in 2008:

The white dingo came to the people and said, ‘Every time the red dingo eats the white dingo he gets bigger, he must be a spirit dog.’ So we said, ‘bring him our way’ and when he came our way the land rose and we trapped him. So now the white dingo helps the Bidjara people. If you come on country without permission the white dingo will get you. The white Dingo is associated with women’s business and is a protector of women’s business. That’s why the Seven Sisters, when they came here had two white dingoes with them (Constable and Love 2015:40).

The solitary star-like design’s location, just above the floor (Figure 13) suggests a ‘fallen’ star and has been interpreted by some community members as possibly one of the Seven Sisters now on Earth hiding from Wattanuri but in some stories there are more than seven Sisters (Greenwood and Taçon 2022; National Museum of Australia 2010:53; Newberry 2017:159). Given the dingo track is above and to the left of this star, there may be an association in terms of the dingo looking out for her.

In terms of a narrative from south to north, and from one end of Marra Wonga to the other, the ten key elements of many Seven Sisters stories can be found in an ordered sequence that can be identified archaeologically through detailed recording, and that makes sense in terms of the contemporary community’s story for Marra Wonga along the lines of: (1) Wattanuri arrives at the southern end of Marra Wonga from Gray Rock to the west in search of the Seven Sisters, (2) he transforms into a snake-like or mythical creature, (3) he checks his footprints to see if his magic is out of control, (4) he emerges as a penis and throws boomerangs at the Seven Sisters (5) an enormous Rainbow Serpent appears (6) and the journey across, and creation of, Country continues. Relations between men and women, varied foods and medicines, and other things are emphasised with boomerang (7), digging stick (8) and ring pad stencils. A dingo (9) looks out for the Seven Sisters and watches over one that remains on Earth (10), with Wattanuri close behind, checking his footprints and magic again (9). This could be embellished with more detail and different aspects of emphasis when people told the Seven Sisters story at Marra Wonga in the past, including reference to the macropod and bird tracks, hand stencils and other rock art, as well as natural holes and features of the rock wall.

For instance, abraded macropod tracks have been interpreted as ‘the footprints of the red kangaroo, which was related to a tribe in the area and is also found extensively in the region’ (Franklin 1998:6). Franklin (1998:5) says that Mate Mate interpreted the site as a male initiation site used in May-June when the Pleiades rise in the east. However, there are hand stencils of children at the southern end of the site, as noted above. This is important as it indicates it was not a restricted men’s or women’s site and was open for all ages to visit.

Across Australia many rock art sites have depictions of important Ancestral Beings associated with the Dreamtime creation era, having stories about Ancestral Beings and/or having story elements depicted, and/or having imagery said to have been made by Ancestral Beings themselves. Often rock art designs are found having been placed in relation to natural features of these sites, making imagery aesthetically powerful but also emphasising the interrelationship between human, natural and Ancestral Being creativity.

The use of natural features on a wall panel, such as cavities, holes, cracks, and changes in orientation, as well as incorporating adjacent rocks, boulders and a natural rock platform (for the 19 multi-toed feet), are significant aspects of Marra Wonga, which integrates natural and cultural creation. Given the nature of the rock art imagery, as described above, Marra Wonga is an extraordinary site in many ways. Its significance has been recognised since at least 1960 when archaeologist Fred McCarthy published a brief description and six photographs. However, until recently, Marra Wonga did not receive the attention or protection that The Palace rock art site has received since the 1960s, despite having a large number of equally impressive but different rock markings, if not more. Gunn (2000:36) stated the Gracevale rock art site (Marra Wonga) is highly significant ‘from an Aboriginal, archaeological and heritage perspective’ due to its ‘importance to the local Aboriginal Community as a tangible manifestation of the prior occupation of the region by the Iningai people’ and an ‘exceptional array of rock art at the regional, State and National levels’ (Gunn 2000:36). He also noted that shelter sites with this number and densities of petroglyphs are uncommon anywhere in Australia, with their most common occurrence in the Central Queensland Highlands to the southwest (Gunn 2000:36).

As noted, engraved human figures are rare in the rock art of the Central Queensland Highlands. Given that the style of the figures at Gray Rock is the same as the anthropomorph at Marra Wonga, we argue that they were probably made by the same individual or group in order to connect the two places in some way, perhaps as part of a Dreaming Track or Songline that features Wattanuri, as outlined above. This connects with the seven star designs interpreted as representing the Seven Sisters at Marra Wonga, as well as the other features described above.

Across Australia, there are at least 83 areas with stories of the Seven Sisters, many extensive Seven Sisters Dreaming Tracks, both related and unrelated, and hundreds of localities on and off the Dreaming Tracks associated with the Seven Sisters story (Greenwood and Taçon 2022). However, the Marra Wonga—Gray Rock locality is one of only four locations where the story is represented with rock art and the four are widely dispersed across the continent. The other three are on previously documented Seven Sisters Dreaming Tracks. For instance, in the west of Western Australia, the Seven Sisters story is associated with a Martu Seven Sisters Dreaming Track, a cluster of petroglyph sites, such as Pangkal (Neale 2017) and an important site called Pimulu, located to the north of Karlamilyi (Rudall River). There the petroglyph assemblage is dominated by concentric circles and mazes (Peter Veth, pers. comm. 17 January 2021), in contrast to Marra Wonga.

In between, in central Australia, there is a pictograph site with paintings associated with the Seven Sisters story, Walinynga/Walinja/Owalinja (also known as ‘Cave Hill’). It is located in South Australia near the Northern Territory border, about 100 kilometres south of Uluru. Tindale (1959) recorded it in May 1957 and reported several layers of painting and all useable surfaces covered. Various Ancestral Beings are said to have visited the cave, including the Seven Sisters (called Kungkarungkara or Kungkarangkalpa), with their male pursuer, Wati Njiru, ‘leaving records of their passage in the cave’ (Tindale 1959:326).

Ross (2017:80) notes that the site has one of the densest collections of paintings she has seen at any desert rock art site, attesting to its importance and continued use in Aboriginal ritual, storytelling and teaching over time. In 1974, the back ceiling area, with the most sacred designs, was painted over with human footprints, animal tracks, concentric circles and other traditional motifs in response to a perceived threat. ‘The resulting art, while traditional in form and richly colourful, does not encode the same array of meanings as the older art. In this way, the totemic integrity of Walinynga was maintained and the site could continue to play a role in both the religious life of Aboriginal people, while enabling them to take advantage of potential economic opportunities from tourism’ (Ross 2017:81). It continues to be a place of guided tourism today.

Ross (2017:78) was particularly struck by the large number of human-like ‘Walinynga’ figures with headdresses, with 67 still visible today and possibly many more in the past. Wati Njiru is also painted there. Some anthropomorphs at Walinynga, including one said to be having coitus with one of the Seven Sisters (Tindale 1959:332 and Plate XXXV A), is similar in form and style to those at Marra Wonga—Gray Rock but this may be a coincidence.

To the southeast is a fourth locality with rock art associated with the Seven Sisters, an extensive engraving site located south of Lake Eyre (Hercus 2012:22). The site and engravings are sacred and restricted so are not described here in respect of the wishes of Traditional Owners.

The Seven Sisters story varies across the Australian continent but like almost all Aboriginal stories/legends it has morals and invaluable information within it. The pursuer of the women is usually always a Clever man, who can shape shift into objects, vegetation (usually a tree) and animals, such as a snake. He can go under the Earth and pop up in the long grass. Importantly, he tests his footprint in some stories and sees that his magic is out of control as the number of his toes keeps changing. Women are often affected by his magic and get sick. They finally do get away by returning to the sky, but are pursued by him further in the sky each night. The Seven Sisters story:

… throughout the Central and Western deserts is a tale of flight and pursuit, as the sisters flee the unwanted attentions of a sorcerer who pursues them relentlessly, spying on them, lying in wait for them, sometimes capturing one or several of them. The violence of his obsession thwarts his attempts to approach the women ‘proper way’, and manifests as a landscape that seethes and ripples with sexual desire, rendered unstable by a force that is both a primal sex organ and a relative of the Ancestral snake that lives in waterholes and creeks - dangerous, unpredictable, everywhere (Mahood 2017:32).

In a global survey of human-like foot petroglyphs, Greenwood and Taçon (2021) found 48 sites with examples of feet with six toes: 21 in Australia, ten in the United States of America, four in Argentina, three in Chile, two in Namibia and New Zealand, and one each in Angola, Botswana, Egypt, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), South Africa and the United Kingdom (Table 4). Of the 21 in Australia, there are nine in Queensland (eight in the Central Queensland Highlands and one in southeast Queensland), three each in the Northern Territory and South Australia, and two each in New South Wales, Tasmania and Western Australia. There are a further 64 sites in Australia with engraved footprints that have other than six toes and 209 sites spread across 48 other countries, with the most sites, 44, in Sweden, followed by 26 in the United States of America and 18 in Norway. For the 64 sites in Australia, 24 are in Queensland, 18 in New South Wales, 13 in South Australia, four in both the Northern Territory and Western Australia and one in Tasmania. Of the total number of sites in Australia so far identified, 85, a quarter or 24.71%, have feet with six toes. This compares to 11.44% for the rest of the world.

In Queensland, footprint petroglyphs are frequent in Bidjara Country to the southeast of Turraburra and in many cases they have six rather than five toes (Kerkhove 2010:13). Bidjara elder Ray Robinson says that ‘six toe signs’ occur throughout Bidjara country (Kerkhove 2010:13) and like the ‘v’ sign, were used ‘… to reinforce regional (group) identity with specific sites’ (Kerkhove 2010:28). Robinson (pers. comm. 2010 to Kerkhove 2010:13) stated that ‘… this related back to the Bidjara families which includes the Murphys, Turners, Frasers and Johnstones, as they sometimes had six toes and six fingers. The Bidjara point to various individuals that manifested this trait, most notably Ray Robinson’s grandmother Ada Lang’s brother—thus his great uncle: Billie Peters’ (Kerkhove 2010:13).

Footprint petroglyphs with six toes are often larger than an average human size (Kerkhove 2010:13) and the two largest at Marra Wonga have six toes (Figures 8 and 12). The Bidjara people state that the six toed footprints represent one of their Dreaming Ancestors, a great Medicine Man leader, who was one of their family (Kerkhove 2010:13). Dhinabay/bay is the Bidjara language word for foot and it forms part of the Bidjara word for witch doctor whittobay. Therefore, six toed footprint petroglyphs in this region are a symbol for a major Medicine Man Ancestor. Across the world, engraved human-like footprints are invariably associated with powerful Ancestors, mythological Beings or religious figures, such as Buddha (Greenwood and Taçon 2021).

Throughout Australia there are numerous rock art sites with depictions of Rainbow Serpents, with the oldest in the Yam Figure style of western Arnhem Land, over 6,000 years of age (Taçon et al. 1996, 2020b). However, nearly all were painted; engraved examples are extremely rare. The Marra Wonga Rainbow Serpent petroglyph is unique in this regard, but it also is one of the largest known depictions of a Rainbow Serpent. Besides being part of some Seven Sisters stories, it probably signifies that the site is also associated with a Rainbow Serpent Dreaming Track or major locality, making it extremely important as a traditional teaching and story-telling place. In some parts of Australia, Rainbow Serpents are said to have placed images of themselves in rock shelters, including at Lilydale Spring in nearby northwest Queensland (Taçon 2008). And across Australia there are numerous accounts of a wide range of Ancestral Beings making rock art, including petroglyphs (e.g. see Rosenfeld 1997; Taçon 2009). Furthermore, McDonald and Veth (2012:7) note that:

Western Desert pigment art is seen by Martu to have been created by humans and this depicts both everyday and secret/sacred themes. Engraved art, on the other hand, is said to have been created in the Dreamtime and is not of human origin. Engravings (or petroglyphs) represent the marks or tracks left behind by creator-beings and are places where the creator beings were literally transmogrified into stone.

Because of the size of Marra Wonga’s rock art panel, the estimated number of designs, their diversity, and the presence of rare imagery, such as the anthropomorph petroglyph and the digging stick stencil, it could be argued that Marra Wonga has features of an aggregation site. According to Conkey (1980:612):

An aggregation site among hunter-gatherers is a place in which affiliated groups and individuals come together … [I]n its basic form an aggregation refers to the concentration of individuals and groups that are otherwise fragmented. The occasions for concentration may be ecologically or ritually/socially prompted, and there must be processes that effect [sic] the integration and allow the aggregation to take place. The duration, however, of an aggregation may vary. Short-term aggregations at ritual locales may occur; subsistence activities may not go on at the same place. Extended multigroup aggregations for subsistence ‘harvest’ and ritual may take place for over several months. Many different persons may move in and out of the aggregated group, so that although group size remains relatively constant, group composition varies radically … [S]ocial relationships among participants in the aggregation may vary. The number of individuals contributing to the material-culture assemblage may also vary considerably. Conkey focused on the painted Spanish cave of Altamira as a case study to explore the nature of aggregation sites and criteria that can be used to identify them. Among other things, Conkey (1980:616) noted that if groups or individuals employing different marking repertoires were aggregating at a site, such as Altamira, at least four things can be expected. First of all, diversity will be greater than at other sites in the area and this is the central criteria. Second, most design elements at the core of the site ‘will be present everywhere or at least [will] be widespread’ (Conkey 1980:616). Third, the site will have some designs ‘and structural principles that are unique’. Lastly, designs lacking at the site ‘should tend not to occur elsewhere’ (Conkey 1980:616).

In terms of Marra Wonga, rock art diversity is greater here than at any other central Queensland site with the exception of The Palace. Marra Wonga is the largest rock art site in central Queensland with at least 15,000 petroglyphs and 111 stencils and it has more petroglyphs on a shelter wall than any other Australian rock art site (Gunn 2000:36). The Palace has a minimum of 9,471 rock art motifs (Morwood 1979:261) and is the second largest rock art site complex in central Queensland, after Marra Wonga. For instance, further south in Carnarvon Gorge the two largest sites, Art Gallery and Cathedral Cave, have 1,989 and 1,669 motifs, respectively (Quinnell 1976:144, 158). However, The Palace has a series of separated rock art panels whereas Marra Wonga is one long continuous panel.

Most of Marra Wonga’s design elements are widespread (e.g. see Morwood 1979, 2002), with some, such as varied hand stencils, found throughout central Queensland, satisfying Conkey’s (1980) second criteria. Marra Wonga also satisfies Conkey’s (1980) third criteria, with unique or rare features, such as the cluster of seven stars, the ‘penis’ petroglyph later framed with red ochre, the digging stick stencil, the 11 metre long engraved snake-like design in the middle of the shelter, the cluster of 19 human-like footprints on the floor, the structure of the entire marked area of the site, and other things. For the fourth criteria, there are many designs not at Marra Wonga that are also not at other central Queensland sites, such as depictions of animals in a naturalistic style, and Marra Wonga ‘is an excellent example of the Central Queensland Rock Art Region and hence of particular preservational value’ (Gunn 2000:36). However, painted grid designs, common at The Palace and some other central Queensland sites, are not found at Marra Wonga.

For Altamira, Conkey (1980:620) concluded that ‘the demonstrated relative diversity of the Altamira engraving repertoire supports the hypothesis that otherwise dispersed engravers contributed to the engravings at Altamira, which may well have been concomitant with a social aggregation of some size and extent’. The same can be said of Marra Wonga in terms of its rock art. Furthermore, for arid zone rock art, McDonald and Veth (2012:91) noted that:

The Australian arid zone is characterized by extensive dune fields, gibber and sand plains, and the opportunities to produce rock art are not continuous. Very low population densities also characterize these social landscapes. The need to signal social information to others may well have been focused in locations where larger groups of people aggregated – for a range of purposes. Well-watered range systems across the arid zone provide highly focalized opportunities for art production, often in association with other vital resources (food, reliable water). These landscapes, with their distinctive and highly variable rock art provinces, represent aggregation nodes for otherwise highly dispersed, arid-zone populations. This is exactly the type of environment in which Marra Wonga is situated, and given its size and the extensive number of varied rock markings, it has all the characteristics of an arid zone ‘aggregation node’.

Marra Wonga was marked with petroglyphs and stencils many times in the past with a vast amount of imagery accumulating over time. Aboriginal interpretation may have changed in various ways in response to additional imagery, contact between different groups, and new cultural exchanges. However, Marra Wonga has consistently been interpreted as a Seven Sisters site since at least the 1990s. There are a wide range of designs and compositions at Marra Wonga, including many that are rare and exceptional. These images have most likely been used, and continue to be used today, to tell important cultural stories and various aspects of traditional culture, law and lore, as well as important relationships between people, animals, plants, ancestors, Ancestral Beings, Dreaming Tracks and landscapes. We have shown one potential way this could be done with a focus on Seven Sisters stories found across Australia, including the region where Marra Wonga is situated, using key visual elements that could be identified, both archaeologically and ethnographically. Marra Wonga also has all the key features of an aggregation site, in terms of its rock art, size and its well-watered position in the landscape, as proposed by Conkey (1980) and elaborated by McDonald and Veth (2012).

Marra Wonga is an extraordinary rock art site worthy of special protection, conservation and management given its many unique features. Consequently, future research will focus not only on conservation and sustainable tourism but also on better quantifying the vast number of petroglyphs and better situating Marra Wonga in regional and national archaeological and cultural contexts.

We thank the many people who have contributed to aspects of our research on Marra Wonga including Graham Ambridge, Uncle Vincent Forrester, Uncle Sam Juparulla Wickman, and Lake Eyre Rangers Jodie Ahkee, Daryl Ah Kee and Liam Timmermans. Three anonymous referees are thanked for their extensive valuable comments that made this paper much stronger and for supporting publication of a revised version.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

This research has been supported by Australian Research Council (grant FL160100123) and Griffith University, Queensland.

1 Anonymous 1900 The Mootaburra Tribe. Science of Man 3(5):82–83. [Google Scholar]

2 Bennett, M.M. 1927 Notes on the Dalleburra Tribe of Northern Queensland. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 57:399–415. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

3 Berndt, R.M. and C.H. Berndt 1982 The World of the First Australians. Sydney: Lansdowne Press. [Google Scholar]

4 Brown, S. and S. Thompson 2020 Gracevale, a case study on Caring for Country and rediscovery of culture and language by the Iningai people in Central west Queensland. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland 128:21–25. [Google Scholar]

5 Clarke, A. 2013 The Christison collection in Edinburgh and Canberra. Journal of Museum Ethnography 26:53–70. [Google Scholar]

6 Conkey, M.W., A. Beltrán, G.A. Clark, J.G. Echegaray, M.G. Guenther, J. Hahn, B. Hayden, K. Paddayya, L.G. Straus and K. Valoch 1980 The identification of prehistoric hunter-gatherer aggregation sites: The case of Altamira. Current Anthropology 21(5):609–630. (with comments by A. Beltrán, G.A. Clark, J. González Echegaray, M.G. Guenther, J. Hahn, B. Hayden, K. Paddayya, L.G. Straus, and K. Valoch) [Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

7 Constable, J. and K. Love 2015 Aboriginal Water Values Galilee Subregion (QLD): A Report for the Bioregional Assessment Programme. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

8 Cooper, J. 2013 Crossing the Divide: A History of Alpha and Jericho Districts. Barcaldine: Barcaldine Regional Council. [Google Scholar]

9 Franklin, N.R. 1998 Management Guidelines for Gracevale Rock Art Site, Central Western Queensland. Unpublished report, Cultural Heritage Branch, Queensland Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane. [Google Scholar]

10 Franklin, N.R. 2003 Current initiatives in rock art management and public education in Queensland. Rock Art Research 20(1):48–52. [Google Scholar]

11 Franklin, N.R., M. Giorgi, P.H. Habgood, N. Wright, J. Gorringe, B. Gorringe, B. Gorringe and M.C. Westaway 2021 Gilparrka Almira, a rock art site in Mithaka Country, southwest Queensland: Cultural connections, dreaming tracks and trade routes. Archaeology in Oceania 56(3):284–303. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

12 Fuller, R.S. 2020 The Astronomy and Songline Connections of the Saltwater Aboriginal Peoples of the New South Wales Coast. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of New South Wales, Sydney. [Google Scholar]

13 Gall, S. 2018 Passing of Barcaldine Tourism Identity. North Queensland Register 9 January 2018. https://www.northqueenslandregister.com.au/story/5156642/tom-lockies-tourism-legacy/. [Google Scholar]

14 Greenway, C.C. 1901 Berryberry, Aboriginal Myth. Science of Man Journal of the Royal Anthropological Society of Australia 4(10):168. [Google Scholar]

15 Greenway, C.C., T. Honery, M. McDonald, J. Rowley, J. Malone and D. Creed 1878 Australian languages and traditions. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 7:232–274. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

16 Greenwood, K. and P.S.C. Taçon 2021 Human Footprint Petroglyphs Especially Those with Six Toes. A Review of Global Sites. Unpublished report, Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit, Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University, Gold Coast. [Google Scholar]

17 Greenwood, K. and P.S.C. Taçon 2022 A Review of Seven Sisters (Pleiades) Stories, Localities and Dreaming Tracks Across Australia. Unpublished report, Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit, Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University, Gold Coast. [Google Scholar]

18 Gunn, R.G. 2000 Gray Rock Historical Reserve and Gracevale Aboriginal Rock Art Site: Interpretation and Visitor Management Plans. Unpublished report to Aramac Shire, Central Western Queensland, and the Queensland Environmental Protection Agency, Stawell. [Google Scholar]

19 Hercus, L.A. 2012 The Journey of the Seven Sisters Through the Lake Eyre Region (as Told by Mick McLean Irinyili); With Some Additional Songs from Laurie Stuart, Tim Strangways, Frank Crombie, and Leslie and Jimmy Russell; And Some Additional Text from Tom Naylon. Unpublished report, Gundaroo. [Google Scholar]

20 Hoch, I. 1986 Barcaldine 1846–1986. Barcaldine: Barcaldine Shire Council. [Google Scholar]

21 Jalandoni, A. 2021 An overview of remote sensing deliverables for rock art research. Quaternary International 572:131–138. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

22 Jalandoni, A. and M. Kottermair 2018 Rock art as micro-topography. Geoarchaeology 33(5):1–15. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

23 Kerkhove, R. 2010 Bidjara Signs: A Report on the Styles of Rock Art, Ceremonial Sites and Other Material Culture in and near The Bidjara Claim Region. Unpublished report prepared for Interactive Community Planning (ICP) Australia Inc., Nambour. [Google Scholar]

24 Mahood, K. 2017 The seething landscape. In M. Neale (ed.), Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters, pp.32–37. Canberra: National Museum of Australia. [Google Scholar]

25 Massola, A. 1968 Bunjil’s Cave. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press. [Google Scholar]

26 Mate Mate, R. (Gapingaru) 1996 Dreamtime Stories Aboriginal Sky Figures. Sydney: ABC Audio (Recording). [Google Scholar]

27 Mathews, R. 1908 Some Mythology and Folklore of the Gundungurra Tribe. Wentworth Falls: Den Fenella Press. [Google Scholar]

28 McCarthy, F.D. 1960 Rock art in Central Queensland. Mankind 5(9):400–404. [Google Scholar]

29 McDonald, J. and P. Veth 2012 The social dynamics of aggregation and dispersal in the Western Desert. In J. McDonald and P. Veth (eds), A Companion to Rock Art, pp.90–102. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

30 Morwood, M.J. 1979 Art and Stone: Towards a Prehistory of Central Western Queensland. Unpublished PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra. [Google Scholar]

31 Morwood, M.J. 2002 Visions from the Past. The Archaeology of Australian Aboriginal Art. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

32 Mulvaney, D.J. and E.B. Joyce 1965 Archaeological and geomorphological investigations at Mt Moffatt Station, Queensland, Australia. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 31:147–212. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

33 National Museum of Australia 2010 Yiwarra Kuju: The Canning Stock Route. Canberra: National Museum of Australia Press. [Google Scholar]

34 Neale, M. (ed.) 2017 Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters. Canberra: National Museum of Australia. [Google Scholar]

35 Newberry, B. 2017 He chased them all the way to this country. In M. Neale (ed.), Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters, pp.158–161. Canberra: National Museum of Australia. [Google Scholar]

36 Norris, M. 1996 Queensland Hotels and Publicans Index (1843–1900). Brisbane: Queensland Family History Society. [Google Scholar]

37 Nugent, P. 2006 Applying use-wear and residue analyses to digging sticks. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(1):89–105. [Google Scholar]

38 Nyoongah, M. 1994 Aboriginal Mythology. London: Harper Collins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

39 Peterson, D. 1996 Handprints in time. Courier Mail 28 September 1996. [Google Scholar]

40 Porter, J.A. 1961 Roll the Summers Back. Brisbane: Jacaranda Press. [Google Scholar]

41 Pratt, J. 1976a Relics Report Form. FG:A2. Brisbane: Archaeology Branch D.A.I.A. [Google Scholar]

42 Pratt, J. 1976b Site Index Form. FG:A2. Brisbane: Archaeology Branch D.A.I.A. [Google Scholar]

43 Prideaux, F., M. Williams and S. Thompson 2019 Managing a Cultural Landscape as Part of an Interconnected Cultural Highway at Gracevale in Central Queensland. Connecting the Seven Sisters Song-Line Across Country Through Rock Art and Cultural Practices. Unpublished paper presented at the Australian Archaeological Association Inc. Annual Conference, Gold Coast, Queensland. [Google Scholar]

44 Quinnell, M.C. 1976 Aboriginal Rock Art in Carnarvon Gorge, South Central Queensland. Unpublished MA thesis, University of New England, Armidale. [Google Scholar]

45 Rose, D.B. 2011 Wild Dog Dreaming. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

46 Rosenfeld, A. 1997 Archaeological signatures of the social context of rock art production. In M. Conkey, O. Soffer, D. Stratmann and N. G. Jablonski (eds), Beyond Art: Pleistocene Image and Symbol, pp.289–300. San Francisco, CA: Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences, Number 23. [Google Scholar]

47 Ross, J. 2017 Kungkarankgkalpa and the art of Walinynga. In M. Neale (ed.), Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters, pp.78–81. Canberra: National Museum of Australia. [Google Scholar]

48 Smith, A. 1994 This El Dorado of Australia. A Centennial History of Aramac Shire. Cairns: James Cook University. [Google Scholar]

49 Smith, J.R. and M.J. Rowland 1991 The Desert Uplands Biogeographical Zone (Queensland): A Heritage Resource Assessment. Unpublished report prepared for the Cultural Heritage Division, Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage, Brisbane and the Australian Heritage Commission, Canberra. [Google Scholar]

50 Stanton, J.P. and M.G. Morgan 1977 Report No.1 The Rapid Selection and Appraisal of Key and Endangered Sites: The Queensland Case Study. Unpublished report to the Queensland Department of Environment, Housing and Community Development, Brisbane. [Google Scholar]

51 State Library of Queensland 2020 Language of the Week: Week Five Iningai. Retrieved 5 November 2020 from

52 Sveiby, K. and T. Skuthorpe 2006 Treading Lightly: The Hidden Wisdom of the World’s Oldest People. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

53 Taçon, P.S.C. 2008 Rainbow colour and power among the Waanyi of northwest Queensland. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 18(2):163–176. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

54 Taçon, P.S.C. 2019 Connecting to the ancestors: Why rock art is important for Indigenous Australians and their well-being. Rock Art Research 36(1):5–14. [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

55 Taçon, P.S.C., K. Greenwood and A. Jalandoni 2020a Marra Wonga (‘Gracevale’) Rock Art Site: A Report into its History and Management. Unpublished report, Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit, Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University, Gold Coast. [Google Scholar]

56 Taçon, P.S.C., M. Wilson and C. Chippindale 1996 Birth of the Rainbow Serpent in Arnhem Land rock art and oral history. Archaeology in Oceania 31(3):103–124. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

57 Taçon, P.S.C., S.K. May, R. Lamilami, F. McKeague, I. Johnston, A. Jalandoni, D. Wesley, I. Domingo, L. Brady, D. Wright and J. Goldhahn 2020b Maliwawa figures – A previously undescribed Arnhem Land rock art style. Australian Archaeology 86(3):208–225. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

58 Tindale, N.B. 1959 Totemic beliefs in the Western Desert of Australia Part 1. Women who became the Pleiades. Records of the South Australian Museum 13(3):305–332. [Google Scholar]

59 Tindale, N.B. 1974 Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Canberra: Australian University Press. [Google Scholar]

60 Wilson, P.R. and P.M. Taylor 2012 Land Zones. Brisbane: Queensland Herbarium, Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts. [Google Scholar]

61 Wright, D. 2022 Preliminary Archaeology Research at Turraburra. Unpublished Report to the Iningai community, Canberra. [Google Scholar]

62 Yovich, U., A. Page and D. Smith 2017 Songlines Audio Journey. Viewed 28 July 2021 at

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation