Sand and Sea: continental and maritime prehistoric cultural and social networks. Aspects of life, in what appear to be two very different environments, demonstrate a close resemblance.

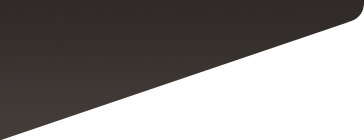

Beyond the Blue Horizon: How the Earliest Mariners Unlocked the Secrets of the Oceans by Brian Fagan is a book that explores humankind's enduring quest to master the oceans, one of the planet's most mysterious terrains. It considers how our mastery of the oceans changed the course of human history. It asks what drove humans to risk their lives on open water, and how early sailors unlocked the secrets of winds, tides, and the stars they steered by.

The colonisation of the South Pacific under sail was an extraordinary feat. It was one thing to seek unseen shores denoted by the distant dark smoke of natural fires caused by lightning strikes, but to sail into the unknown was quite another. Fagan explains this with an explanation of sophisticated marine technology and navigation as well as an understanding of the myths and conceptions that allowed it to take place. He plays down the wanderlust and the 'explore gene' and places greater emphasis on the social motivation of 'privileged lineage' and the founding of 'descent lines firmly anchored in new lands.' In so doing, this concept heralded a cultural innovation: 'for the first time anywhere, people shifted food resources instead of moving to them.'

Moreover, the daunting loneliness of an island complex within an immense ocean was assuaged by an entirely practical and social device known as the 'Kula Ring'; the vast reaches of an aquatic expanse were coded and mapped into a collective prehistoric consciousness and perception.

The Kula Ring, a ceremonial exchange system conducted in the vast Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea, existed long before it was identified by the 'western' anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski. It was a cultural and social network that both connected distant oceanic communities as well as defined the space between them.

Malinowski argued that the concept and practice represented the universality of rational decision-making within prehistoric societies. In his thesis 'Argonauts of the Western Pacific' (1922) he asked why societies would risk life and limb to travel across huge expanses of dangerous ocean to give away what appear to be worthless trinkets. But this complex system of gifts, whose rules were laid down by custom and based on trust, was not about the trinkets; it was all about the cultural contact and interaction over time and over space.

In The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin, we learn of another collective prehistoric consciousness and perception, but on land:

White men, he began, made the common mistake of assuming that, because the Aboriginals were wanderers, they could have no system of land tenure. This was nonsense. Aboriginals, it was true, could not imagine territory as a block of land hemmed in by frontiers: but rather as an interlocking network of 'lines' or 'ways through'.

All our words for 'country', he said, are the same as the words for 'line.'

For this there was one simple explanation. Most of Outback Australia was arid scrub or desert where rainfall was always patchy and where one year of plenty might be followed by seven years of lean. To move in such landscape was survival: to stay in the same place suicide. The definition of a man's 'own country' was 'the place in which I do not have to ask'. Yet to feel 'at home' in that country depended on being able to leave it. Everyone hoped to have at least four 'ways out', along which he could travel in a crisis. Every tribe - like it or not - had to cultivate relations with its neighbour.

So if A had fruits,' said Flynn, 'and B had duck and C had an ochre quarry, there were formal rules for exchanging these commodities, and formal routes along which to trade.'

What the whites used to call the 'Walkabout' was, in practice, a kind of bush-telegraph-cum-stock-exchange, spreading messages between peoples who never saw each other, who might be unaware of the other's existence.

This trade, he said, was not trade as you Europeans know it. Not the business of buying and selling for profit! Our people's trade was always symmetrical.

Aboriginals, in general, had the idea that all 'goods' were potentially malign and would work against their possessors unless they were forever in motion. The 'goods' did not have to be edible, or useful. People liked nothing better than to barter useless things - or things they could supply for themselves: feathers, sacred objects, belts of human hair.

Trade goods should be seen rather as the bargaining counters of a gigantic game, in which the whole continent was the gaming board and all its inhabitants players. 'Goods' were tokens of intent: to trade again, meet again, fix frontiers, intermarry, sing, dance, share resources and share ideas.

A shell might travel from hand to hand, from the Timor Sea to the Bight, along 'roads' handed down since time began. These 'roads' would follow the line of unfailing waterholes. The waterholes, in turn, were ceremonial centres where men of different tribes would gather.

The trade route is the Songline, said Flynn. Because songs, not things, are the principal medium of exchange. Trading in 'things' is the secondary consequence of trading in song.

Read more:

The Australian Rock Art Archive

Read the Book Review:

Beyond the Blue Horizon

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 23 June 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 June 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 29 March 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 15 April 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 27 March 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 04 March 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 05 February 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 04 February 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 June 2014

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 31 January 2014

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2014

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 19 June 2009

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 09 October 2008

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 23 June 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 June 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 29 March 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 15 April 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 27 March 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 04 March 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 05 February 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 04 February 2015

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 June 2014

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 31 January 2014

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2014

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 19 June 2009

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 09 October 2008

Friend of the Foundation