An article on phys.org from AFP - Decorated bird bone suggests Neanderthals had eye for esthetics - reports on the 40,000 year old piece of raven bone that was etched by Neanderthals with near-even lines.

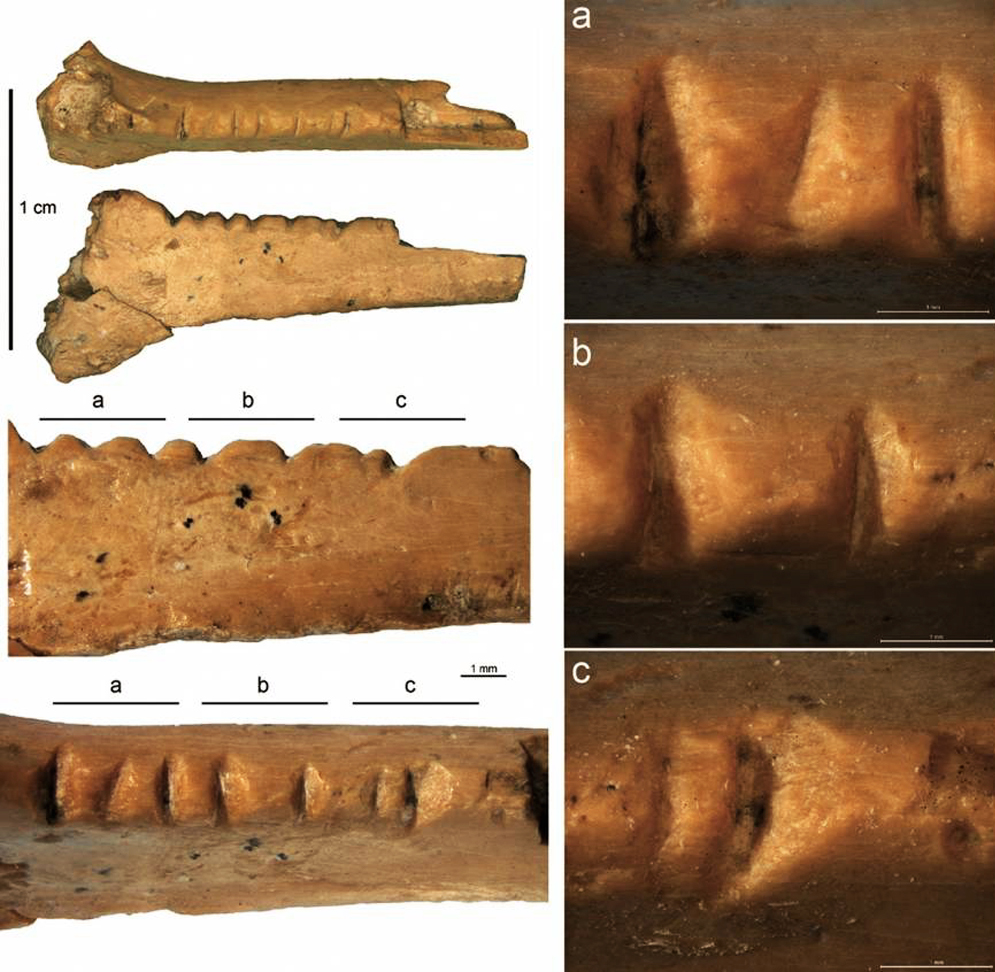

Notched raven bone from Zaskalnaya VI Neanderthal site, Crimea. Image: Francesco d'Errico.

French researchers believe this piece of bone provides further evidence of an aesthetic sense which can be attributed to the Neanderthals.

Neanderthals are known to have used pigments, collected bird feathers and shells, and buried objects with their dead.

This 1.5 cms piece of bone found at an archaeological site in Crimea suggests they may have etched lines in a way that appear deliberate, and which may have been decorative, possibly symbolic.

Neanderthal carved raven bone - etched lines deliberate, decorative & possibly symbolic.https://t.co/1dIxk0kf5O #Crimea #archaeology pic.twitter.com/f1MLJETnrF

— Bradshaw Foundation (@BradshawFND) March 30, 2017

Experimental notching of a bird bone, and sequences of experimental notches compared to those from Zaskalnaya VI. Image: Francesco d'Errico.

Microscopic analysis showed that six grooves were added at first, and two more later, perhaps to make the distance between them more even.

Researcher Francesco d'Errico, a paleontologist with the University of Bordeaux, and lead author of the study in the journal PLOS ONE, refers to it as the 'intent of creating a visually harmonious motif'.

A decorated raven bone from the Zaskalnaya VI (Kolosovskaya) Neanderthal site, Crimea

Ana Majkić, Sarah Evans, Vadim Stepanchuk, Alexander Tsvelykh, Francesco d'Errico

Published: March 29, 2017

Abstract

We analyze a radius bone fragment of a raven (Corvus corax) from Zaskalnaya VI rock shelter, Crimea. The object bears seven notches and comes from an archaeological level attributed to a Micoquian industry dated to between 38 and 43 cal kyr BP. Our study aims to examine the degree of regularity and intentionality of this set of notches through their technological and morphometric analysis, complemented by comparative experimental work. Microscopic analysis of the notches indicate that they were produced by the to-and-fro movement of a lithic cutting edge and that two notches were added to fill in the gap left between previously cut notches, probably to increase the visual consistency of the pattern. Multivariate analysis of morphometric data recorded on the archaeological notches and sets of notches cut by nine modern experimenters on radii of domestic turkeys shows that the variations recorded on the Zaskalnaya set are comparable to experimental sets made with the aim of producing similar, parallel, equidistant notches. Identification of the Weber Fraction, the constant that accounts for error in human perception, for equidistant notches cut on bone rods and its application to the Zaskalnaya set of notches and thirty-six sets of notches incised on seventeen Upper Palaeolithic bone objects from seven sites indicate that the Zaskalnaya set falls within the range of variation of regularly spaced experimental and Upper Palaeolithic sets of notches. This suggests that even if the production of the notches may have had a utilitarian reason the notches were made with the goal of producing a visually consistent pattern. This object represents the first instance of a bird bone from a Neanderthal site bearing modifications that cannot be explained as the result of butchery activities and for which a symbolic argument can be built on direct rather than circumstantial evidence.

The regularity of the marks points to a deliberate action which required a certain level of expertise.

This is the first study of its kind that provides direct evidence to support a symbolic argument for intentional modifications on a bird bone.

Visit the ORIGINS section:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/origins/index.php

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 22 May 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 10 November 2023

Friend of the Foundation