Now, scientists led by Brandi MacDonald, who specializes in ancient pigments, at the University of Missouri are using archaeological science to understand how ochre paint was created by hunter-gatherers in North America to produce rock art located at Babine Lake in British Columbia. The study was published in Scientific Reports, a journal of Nature.

MacDonald explains that "ochre is one of the only types of material that people have continually used for over 200,000 years, if not longer. Therefore, we have a deep history in the archeological record of humans selecting and engaging with this material, but few people study how it's actually made."

This is the first study of the rock art at Babine Lake. It shows that individuals who prepared the ochre paints harvested an aquatic, iron-rich bacteria out of the lake—in the form of an orange-brown sediment.

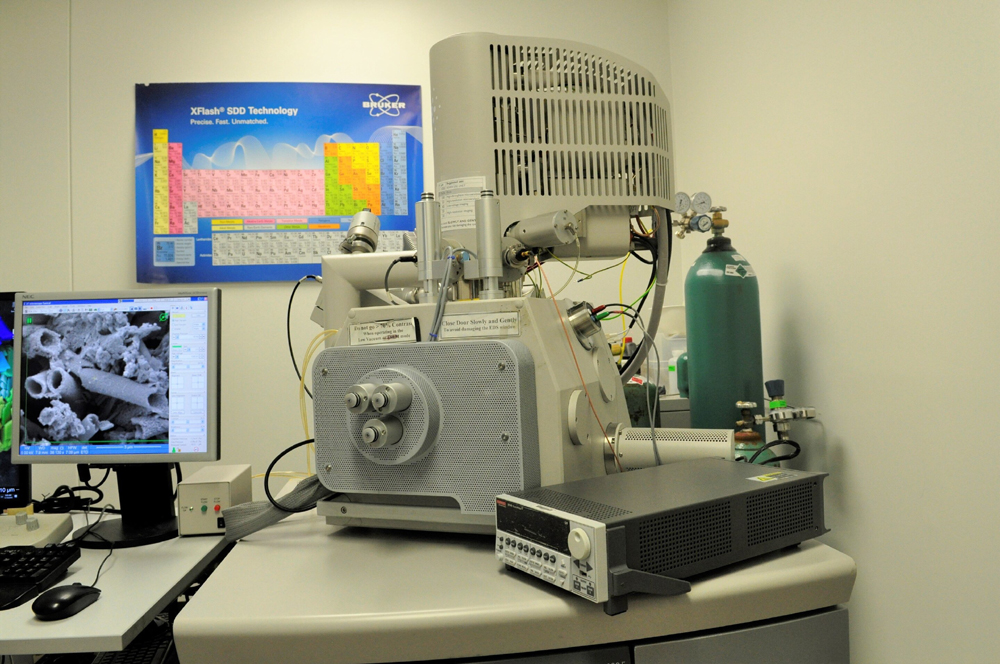

In the study, the scientists used modern technology, including the ability to heat a single grain of ochre and watch the effects of temperature change under an electron microscope at MU's Electron Microscopy Core facility. They determined that individuals at Babine Lake deliberately heated this bacteria to a temperature range of approximately 750°C to 850°C to initiate the color transformation.

MacDonald goes on to explain that it's "common to think about the production of red paint as people collecting red rocks and crushing them up. Here, with the help of multiple scientific methods, we were able to reconstruct the approximate temperature at which the people at Babine Lake were deliberately heating this biogenic paint over open-hearth fires. So, this wasn't a transformation done by chance with nature. Today, engineers are spending a lot of money trying to determine how to produce highly thermo-stable paints for ceramic manufacturing or aerospace engineering without much known success, yet we've found that hunter-gatherers had already discovered a successful way to do this long ago."

click here to read more about the ancient use of ochre in rock art

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 22 May 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 10 November 2023

Friend of the Foundation