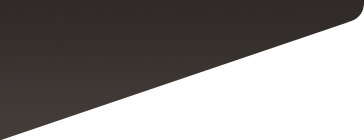

The Bradshaw Foundation joins RARI in congratulating Emeritus Professor David Lewis-Williams on receiving the Order of the Baobab in the Gold Class from President Zuma. This is one of the highest honours South Africa can bestow. The honour was awarded for his outstanding contribution to South African archaeology.

For decades researchers believed that San rock paintings such as those at Game Pass shelter in the Drakensberg Mountains (below) were simply a record of daily life or a primitive form of hunting magic. Our understanding of the art was only moved forward when researchers sought out an insider's rather than an outsider's view of the art. By linking specific San beliefs to recurrent features in the art, David Lewis-Williams managed to crack the fundamental code underlying San rock art. What was revealed was one of the most complex and sophisticated of all the world's symbolic arts. The rock art of Game Pass shelter played a key role in this process.

Game Pass shelter is filled with paintings of eland. As researchers turned from a Western to a San view of the art, they realised that the eland was far more important in San culture than just a food animal. For the San, the eland was god's special animal, the one most filled with his magical power and potency. Even today, many San groups draw upon eland power in their rituals. And the eland at Game Pass are shown in a variety of strange postures that show a magical element in the art. Many of the eland are shown with knees bent and heads lowered. This is a dying posture. The significance of this posture was recognised when the central Game Pass panel, the so-called Rosetta Stone, was decoded.

David Lewis-Williams noticed that the man standing behind the eland (top image) holding its tail, had features that intentionally mirrored features of the eland. Its legs were crossed, it had hair standing on end; it even had eland hooves. The San ethnography tells us that this was not just any man - the man holding the tail was becoming eland, taking on eland power. This is something that San healers describe happening during their trance dances. Lewis-Williams realised further that the dying posture was a metaphor. The San say that they die in the dance; for them trance is a form of death, even if just a temporary death. The dying eland does not therefore only represent potency; it is also a metaphor for the dying dancer. The secret code was unravelling and, as it did, other elements of the panels suddenly started to make sense. The stick in the man's hand was the dancing stick often used by shamans in the dance. The white line inside of the man represented the potency rising up the spine of the dancer from its seat in his stomach. The dots around the man represented the potency exploding out from his body.

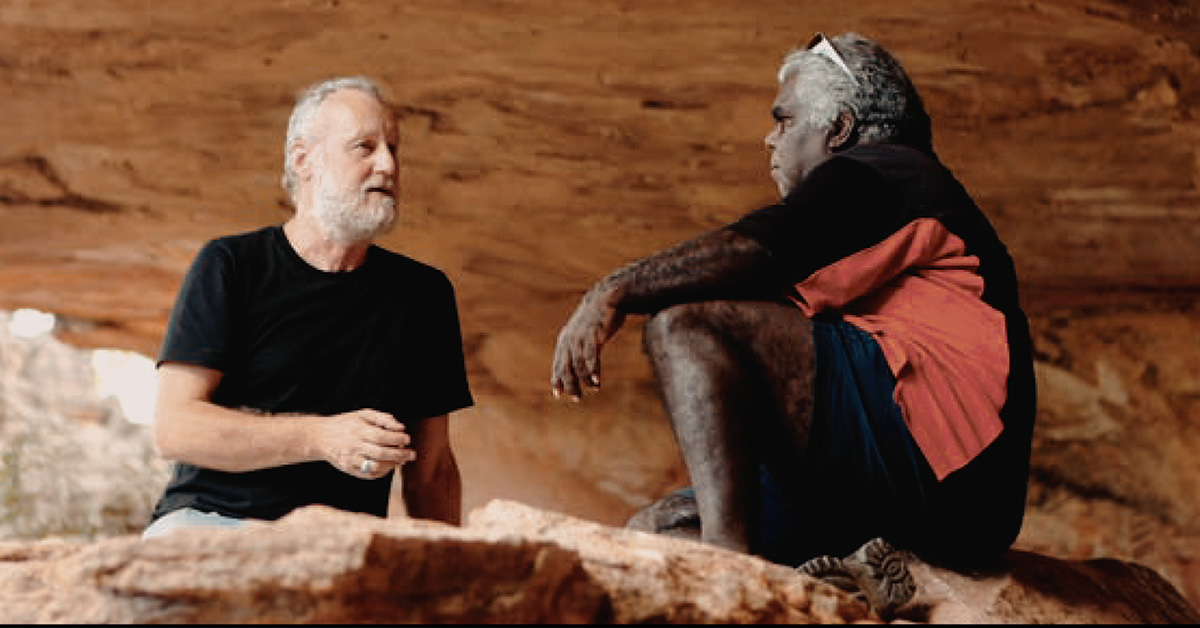

Lewis-Williams realised that far from a general view of San life, the art was focused on a particular parts of San experience: the spirit world journeys and experiences of San doctors, or shamans. Thus many features depict aspects of the all important trance dance, the venue in which San shamans gained access to the spirit world, access through the ritual dance; around a flickering fire, with the chants of women, rhythmic clapping, and hyperventilation, the spirit leaves the body, travelling to the world of trance. Here the San will have powerful visions, visions of god's place, visions of magical things. Upon their return they can use the power and the knowledge that they have harnessed for the benefit of the group. The shamans (above) have climbed up the 'threads of light' that connect people to the sky-world.

Visit the Rock Art Archive of South Africa:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/south_africa/index.php

There are several publications by David Lewis-Williams in our Book Review:

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 22 May 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 10 November 2023

Friend of the Foundation