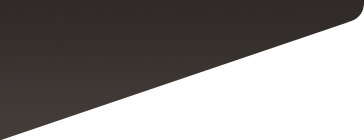

Kindred: Neanderthal life, love, death and art

by Rebecca Wragg Sykes

Bloomsbury Sigma

Product details: ISBN-10 : 147293749X Hardcover : 400 pages ISBN-13 : 978-1472937490 Product Dimensions : 24.1 x 3.8 x 16.2 cm Publisher : Bloomsbury Sigma (20 Aug. 2020)

Kindred is the definitive guide to the Neanderthals. Since their discovery more than 160 years ago, Neanderthals have metamorphosed from the losers of the human family tree to A-list hominins.

In Kindred, Rebecca Wragg Sykes uses her experience at the cutting-edge of Palaeolithic research to share our new understanding of Neanderthals, shoving aside clichés of rag-clad brutes in an icy wasteland. She reveals them to be curious, clever connoisseurs of their world, technologically inventive and ecologically adaptable. They ranged across vast tracts of tundra and steppe, but also stalked in dappled forests and waded in the Mediterranean Sea. Above all, they were successful survivors for more than 300,000 years, during times of massive climatic upheaval.

At a time when our species has never faced greater threats, we're obsessed with what makes us special. But, much of what defines us was also in Neanderthals, and their DNA is still inside us. Planning, co-operation, altruism, craftsmanship, aesthetic sense, imagination, perhaps even a desire for transcendence beyond mortality.

About the Author: REBECCA WRAGG SYKES has been fascinated by the vanished worlds of the Pleistocene ice ages since childhood, and followed this interest through a scientific career researching the most enigmatic characters of all, the Neanderthals.

Alongside her academic expertise, Rebecca has earned a reputation for exceptional public communication as a speaker, in print and broadcast. Her writing has featured in the Guardian, Aeon and Scientific American, and she has appeared on history and science programmes for BBC Radio 4. She works as an archaeological and creative consultant, and co-founded the influential TrowelBlazers project, highlighting women in archaeology and the earth sciences.

Bradshaw Foundation - Editor's Review:

Rebecca Wragg Sykes informs us in Kindred that in just 10 years genetics has overtaken archaeology; 'Genetics opened up a world where Neanderthals from different lineages moved across continents.'

Not that archaeologists have been dithering. The forensic analysis described in this book is so thorough, it leaves you with the impression that you actually know Shanidar 1 and Old Man, because as the author states '...we can reconstruct in quite outstanding detail the conditions in which Neanderthals lived at any point in time, and also what the world was like when they disappeared.' Put another way, 'a hand's breadth thickness may be a palimpsest of a thousand summers' and measuring the true number of occupations represented by particular layers is now possible due to ingenious methods such as fuliginochronology. From her book I now see that it's all about the hearth; 'Hearths are archaeological touchstones. They lie at the centre, where the warp of time and weft of space connect....We don't need to see them sitting face to face; we can literally see it in the way artefacts encircle the ashes and the charcoal.' That's why Shanidar 1 and Old Man seem so familiar.

As I began the book I found myself constantly asking myself 'What happened?' This question became louder and louder as Wragg Sykes calmly reveals numerous aspects of the Neanderthal culture, their ingenuity and their adaptability. From the crafted spears and the left-side bones chosen as tools for right-handers at Schöningen to the evidence of composite tools, craft specialisation and collaboration. From the diverse hunting strategies indicated by the variety of habitats and faunal behaviour to the supplementary diets of plants and the use of fire to cook. The author is able to describe organized living spaces as well as a fundamentally nomadic tendency that involved cultural 'exchange'.

'Bruniquel' then turns our attention to 'Beautiful Things'. Two circular forms constructed from stalagmites - over 400 pieces - some 174,000 years ago deep in a cave. As the author points out, 'Bruniquel laughs in the face of austere, survival-only explanations for Neanderthal behaviour.' She proceeds carefully; 'Ascribing any level of formal spirituality to Neanderthals would go far beyond the archaeological evidence, but they too encountered all of life's sensory marvels.' Yes, there is evidence of art. No, it is not representational. But before we analyze that, Wragg Sykes asks us to consider what criteria we are applying to the Neanderthal culture. Take, for example, 'death'; 'Death and its handling have always mattered. Along with art and symbolism, some of the fiercest debates about Neanderthals have concerned what they did with their deceased. Despite advances in the past three decades, and even a newly discovered skeleton, understanding what mortality meant to them is still controversial.' Her analysis of the evidence relating to their grieving process and mortuary traditions makes intriguing reading.

And then came 2010. First we hear about the Denisovans, and then we learn that the first Neanderthal genome showed they had directly contributed to our own ancestry - between 1.8 and 2.6 per cent Neanderthal DNA in everyone except those of sub-Saharan heritage. What follows is fascinating. For example, however they were conceived, how were hybrid children raised to survive? What were the benefits of interbreeding for H. sapiens in terms of new pathogens encountered whilst on the move? Did this immunity work both ways (or should I say 3 ways) or was there the possibility of a debilitating contagion? Finally, the author asks if there was a 'light-bulb moment' caused by a new genetic mutation which heralded 'more formalised artistic traditions, or flashy burials'?

Kindred is beautifully written, it's convincing, and it's full of surprises. It employs the very latest science to construct a very full and clear picture whilst avoiding over-interpretation. Most importantly, it presents a fascinating story not just of Neanderthals but of ourselves, and we would all do well to pay heed to the sobering thoughts of the Epilogue.

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 22 May 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 10 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 12 January 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 10 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 03 September 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 26 August 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Saturday 27 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 28 April 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 22 May 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 10 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 12 January 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 10 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 03 September 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 26 August 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Saturday 27 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 28 April 2020

Friend of the Foundation