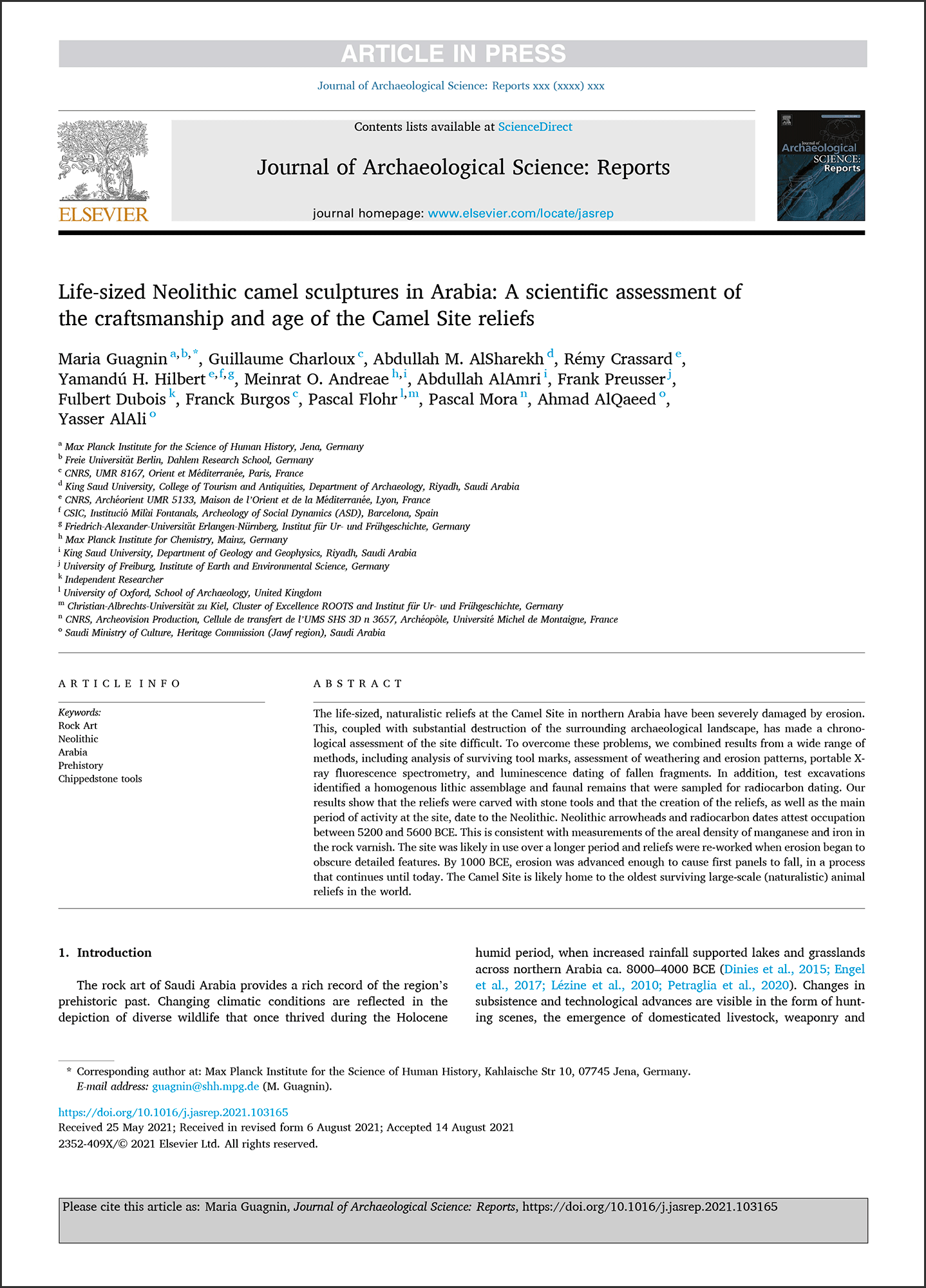

Guagnin, M., Charloux, G., AlSharekh, A.M., Crassard, R., Hilbert, Y.H, Andreae, M.O., AlAmri, A., Preusser, F., Dubois, F., Burgos, F, Flohr, P., Mora, P., AlQaeed, A., AlAli, Y. 2021. Life-sized Neolithic camel sculptures in Arabia: A scientific assessment of the craftsmanship and age of the Camel Site reliefs. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Abstract

The life-sized, naturalistic reliefs at the Camel Site in northern Arabia have been severely damaged by erosion. This, coupled with substantial destruction of the surrounding archaeological landscape, has made a chrono- logical assessment of the site difficult. To overcome these problems, we combined results from a wide range of methods, including analysis of surviving tool marks, assessment of weathering and erosion patterns, portable X- ray fluorescence spectrometry, and luminescence dating of fallen fragments. In addition, test excavations identified a homogenous lithic assemblage and faunal remains that were sampled for radiocarbon dating. Our results show that the reliefs were carved with stone tools and that the creation of the reliefs, as well as the main period of activity at the site, date to the Neolithic. Neolithic arrowheads and radiocarbon dates attest occupation between 5200 and 5600 BCE. This is consistent with measurements of the areal density of manganese and iron in the rock varnish. The site was likely in use over a longer period and reliefs were re-worked when erosion began to obscure detailed features. By 1000 BCE, erosion was advanced enough to cause first panels to fall, in a process that continues until today. The Camel Site is likely home to the oldest surviving large-scale (naturalistic) animal reliefs in the world.

→ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352409X21003771?via%3Dihub

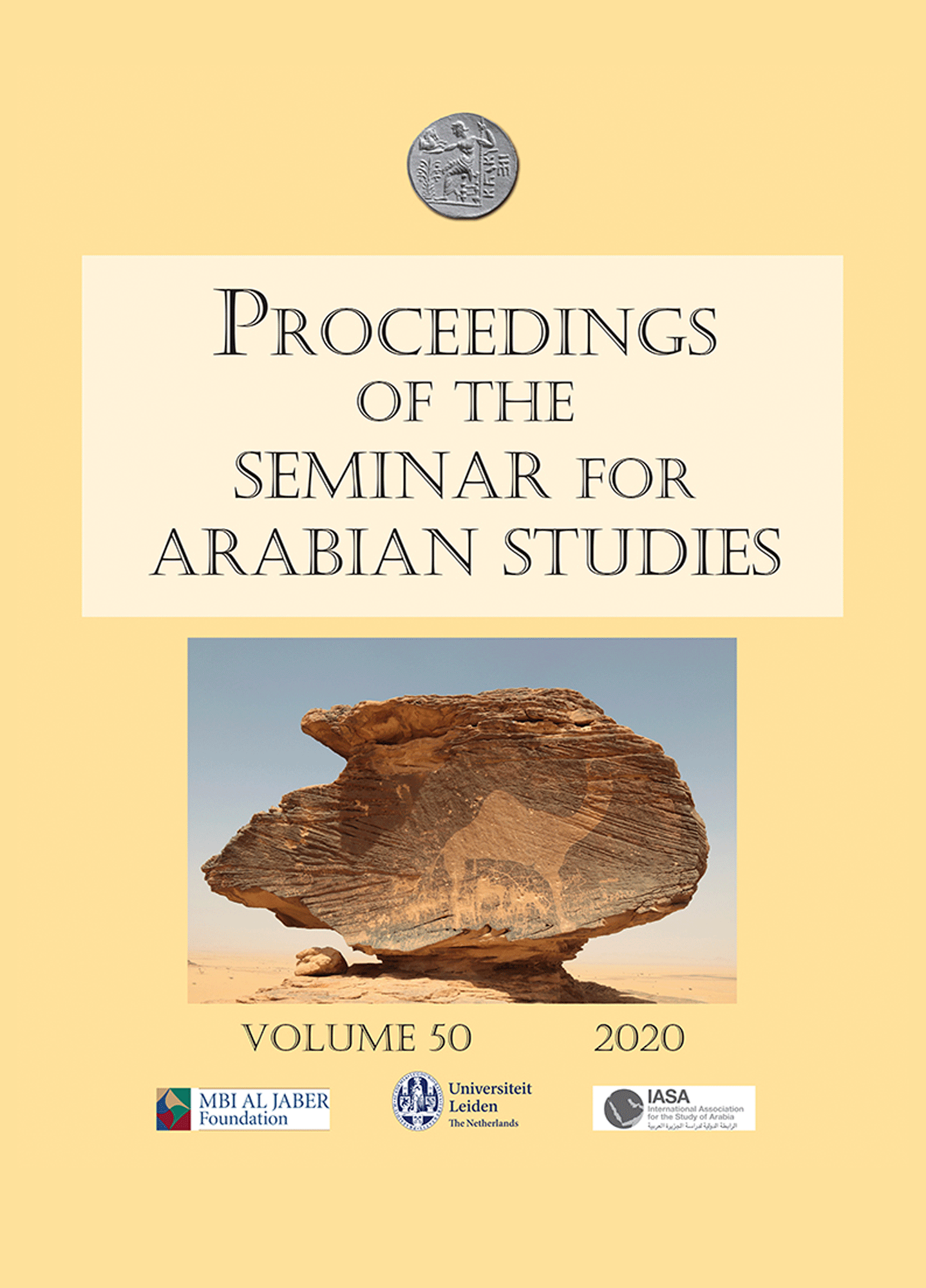

Charloux, G., Guagnin, M., Norris, J. 2020. Large-sized camel depictions in western Arabia: A characterisation across time and space. Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 50, 85-108.

Summary

Rock art is undoubtedly one of the most impressive testimonies left by the ancient inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula over the course of several millennia. While the study of this rich heritage is still in its early stages, the present paper draws attention to the existence of a remarkable and almost unknown artistic phenomenon attested in the western part of the Peninsula, which consists of large-sized representations of camels (Camelus dromedarius), arguably the most ‘characteristic’ animal species of Arabia. Life- size, and sometimes larger-than-life, carvings of camels have been reported across a large area that stretches from the Najrān area in southern Saudi Arabia northwards to Petra, in southern Jordan. Although it is possible that the carvings share a common cultural substratum, these different figures clearly do not form a homogeneous group. At least six different regional rock art traditions can be identified. The present paper provides a first characterization of their stylistic features, chronological setting, and the technical skills involved, and also considers the epigraphic inscriptions which occasionally accompany large-sized camel engravings. In addition, we explore the cultural and environmental background of the communities and individuals that created them and examine this monumental rock art theme over the longue durée.

Guillaume Charloux, Maria Guagnin, Abdullah M. Alsharekh, Ahmed Al-Qaeed

Introduction

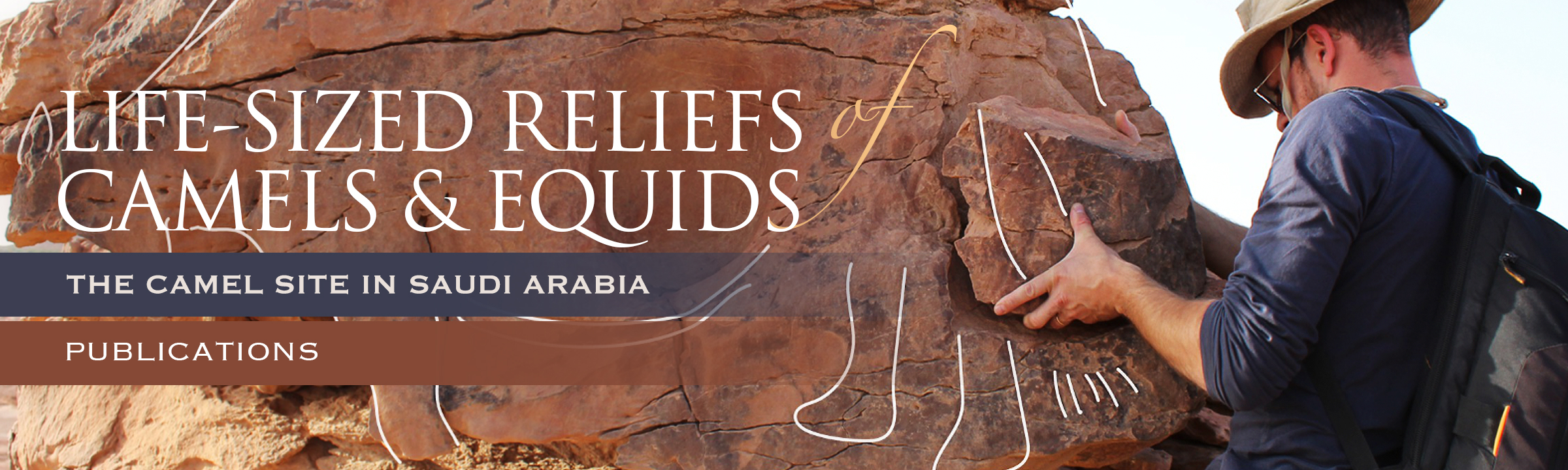

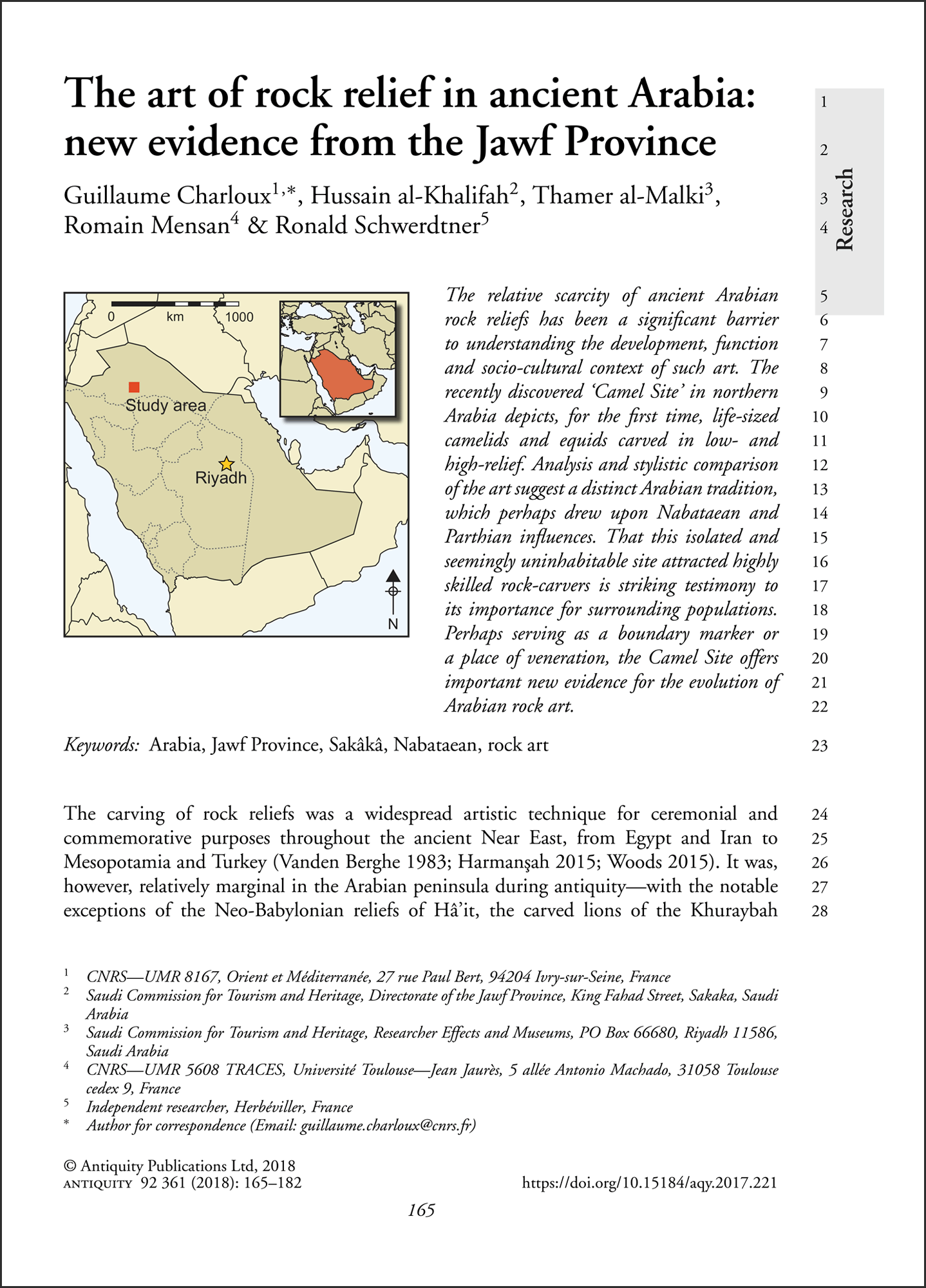

The life-sized and extremely detailed reliefs of the Camel Site near Sakaka (Jawf Province) are unique in the ancient Near East (fig. 1). To date, 12 reliefs are known, which depict at least 10 camels (Camelus dromedarius), three equids (likely Equus africanus, Equus africanus asinus or Equus hemionus) and four unidentifiable animals1. Despite an advanced state of erosion on all panels, surviving details such as the depiction of nostrils, lips or the muscles of the legs attest to a great attention to detail. The time and ef- fort that the engravers invested into the creation of these monumental reliefs are indicative of the impor- tance camels and equids once had for the prehistoric populations of Arabia. Domesticated camels and donkeys were essential for survival in hostile and barren regions, where they were used to carry loads across great distances, and as a source of milk and meat2. We also know from rock art scenes that their wild ancestors were frequently hunted3. The reliefs at the Camel Site appear to show camels and equids in their natural state. To date no evidence for domestication or human control of the animals has been identified, and human figures appear to be absent.

The exceptionally skilled use of high and bas relief, and the depiction of life-sized, naturalistic cam- els and equids, are unparalleled on the Arabian Peninsula. Moreover, the complete absence of contem- porary inscriptions and the scarcity of other types of petroglyphs is surprising, given the location of the Camel Site in a region that is culturally rich throughout prehistory4. The location and character of the site thus raise a number of questions:

- What was the function or possible symbolic significance of the site?

- Who carved these reliefs and why do they not occur anywhere else in Arabia?

- What techniques and tools were used to carve these majestic animals?

- How old are the reliefs and how long was the site in use?

→ The Camel Site: Rock Reliefs of Life-Sized Camels and Equids in the Arabian Desert

Charloux, G., Al-Khalifah, H., Al-Malki, T., Mensan, R. & Schwerdtner, R. 2018. The art of rock relief in ancient Arabia: new evidence from the Jawf Province. Antiquity, 92, 165-182.

Abstract

The relative scarcity of ancient Arabian 5 rock reliefs has been a significant barrier 6 to understanding the development, function 7 and socio-cultural context of such art. The 8 recently discovered ‘Camel Site’ in northern 9 Arabia depicts, for the first time, life-sized 10 camelids and equids carved in low- and 11 high-relief. Analysis and stylistic comparison 12 of the art suggest a distinct Arabian tradition, 13 which perhaps drew upon Nabataean and 14 Parthian influences. That this isolated and 15 seemingly uninhabitable site attracted highly 16 skilled rock-carvers is striking testimony to 17 its importance for surrounding populations. 18 Perhaps serving as a boundary marker or 19 a place of veneration, the Camel Site offers 20 important new evidence for the evolution of 21 Arabian rock art.