Anthony Manhire

Spatial Archaeology Research Unit, Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7700, South Africa.

This paper was originally published in the The South African Archaeological Bulletin, Vol. 53, No. 168 (Dec., 1998), pp. 98-108. It is reproduced here with the permission of Janette Deacon. Janette Deacon is a South African archaeologist specializing in heritage management and rock art conservation. She has been involved in archaeological research on the Later Stone Age and rock art in southern Africa since the early 1960's. She is a member of the Rock Art Network, established by the Getty Conservation Institute and the Bradshaw Foundation, comprises individuals and institutions committed to the promotion, protection, and conservation of rock art globally.

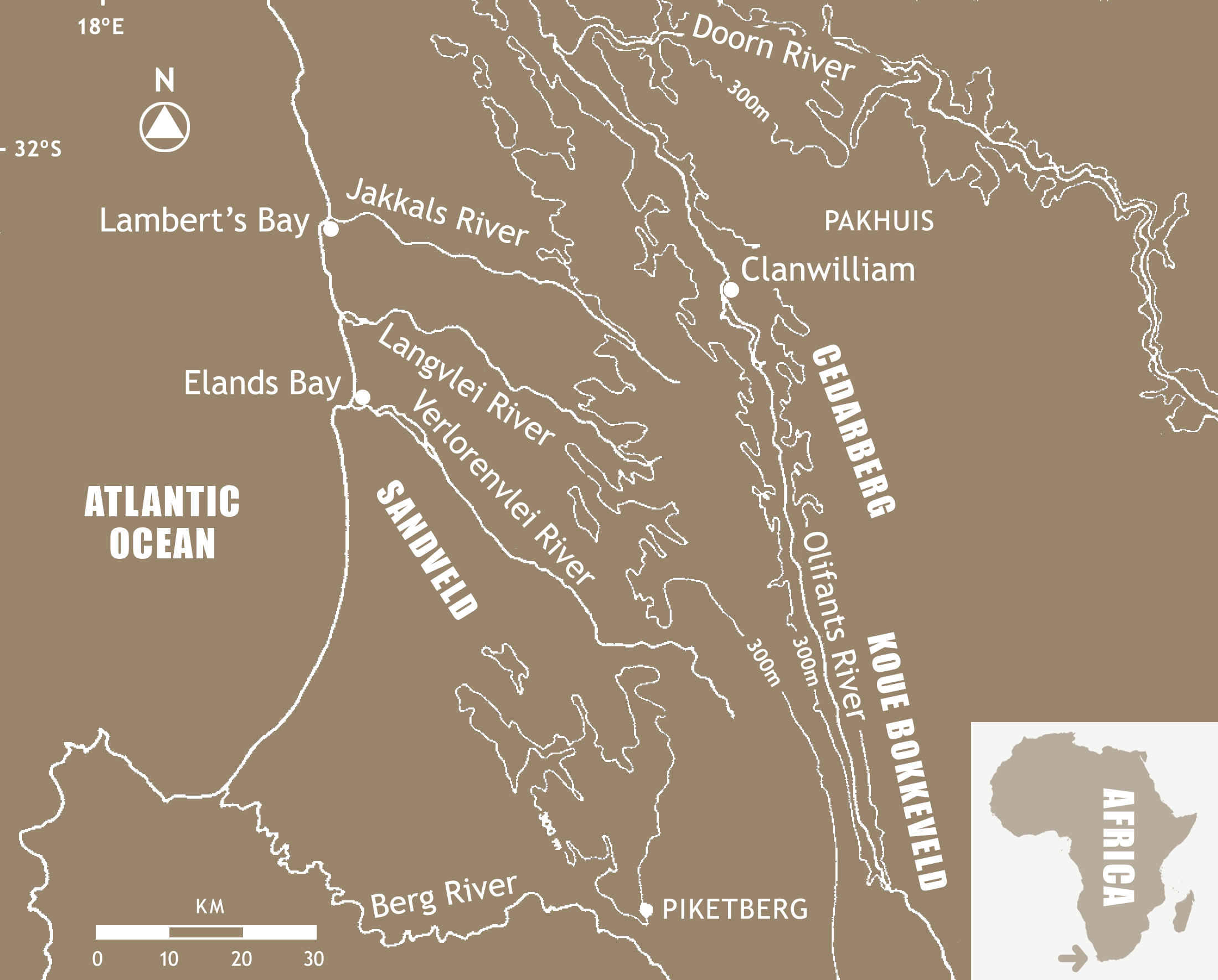

Map of research area in the south-western Cape showing places and areas mentioned in the text.

Hand prints comprise an unusual category in south- western Cape rock art with a status somewhere between a print and a painting. Despite receiving much attention, the significance or meaning of hand prints within the spectrum of rock art images has remained elusive. With more detailed information now available on the form, size range, context, distribution and dating of hand prints, however, we can begin to assess the role they played in the lives of the people who produced them. This paper describes the different types of hand prints and their distributions in the south-western Cape. The results of the measurement of a sample of hand prints from two different localities are presented, the objectives being to reconstruct age and height profiles of the people who made the hand prints. The paper concludes with a discussion of some of the reasons why hand- printing occurred and the role hand prints played in the rock art of the south-western Cape.

Hand prints from the south-western Cape.

(a) Plain hand print from Nuwedam in the Cedarberg.

(b) Decorated hand print from Rooiberg on the Verlorenvlei.

(c) Decorated hand print from Matjies-goedkloof near the Doomn River.

All Western Cape hand prints are positive prints as opposed to the negative or 'stencilled' variety which are the rule in many localities outside of southern Africa such as in Palaeolithic cave art of France (Sieveking 1979) and much of Australia (Walsh 1988). There are, however, two different varieties of hand print in the south-western Cape: the normal plain print and the so-called decorated or lined version. The decorated print is a variation on the plain form effected by scraping off a pattern, usually nested curves or 'U' shapes, on the already paint smeared palm or hand prior to imprinting on the cave wall. Both types of hand print occur in the research area shown in Fig. 1 and both are illustrated in Fig. 2.

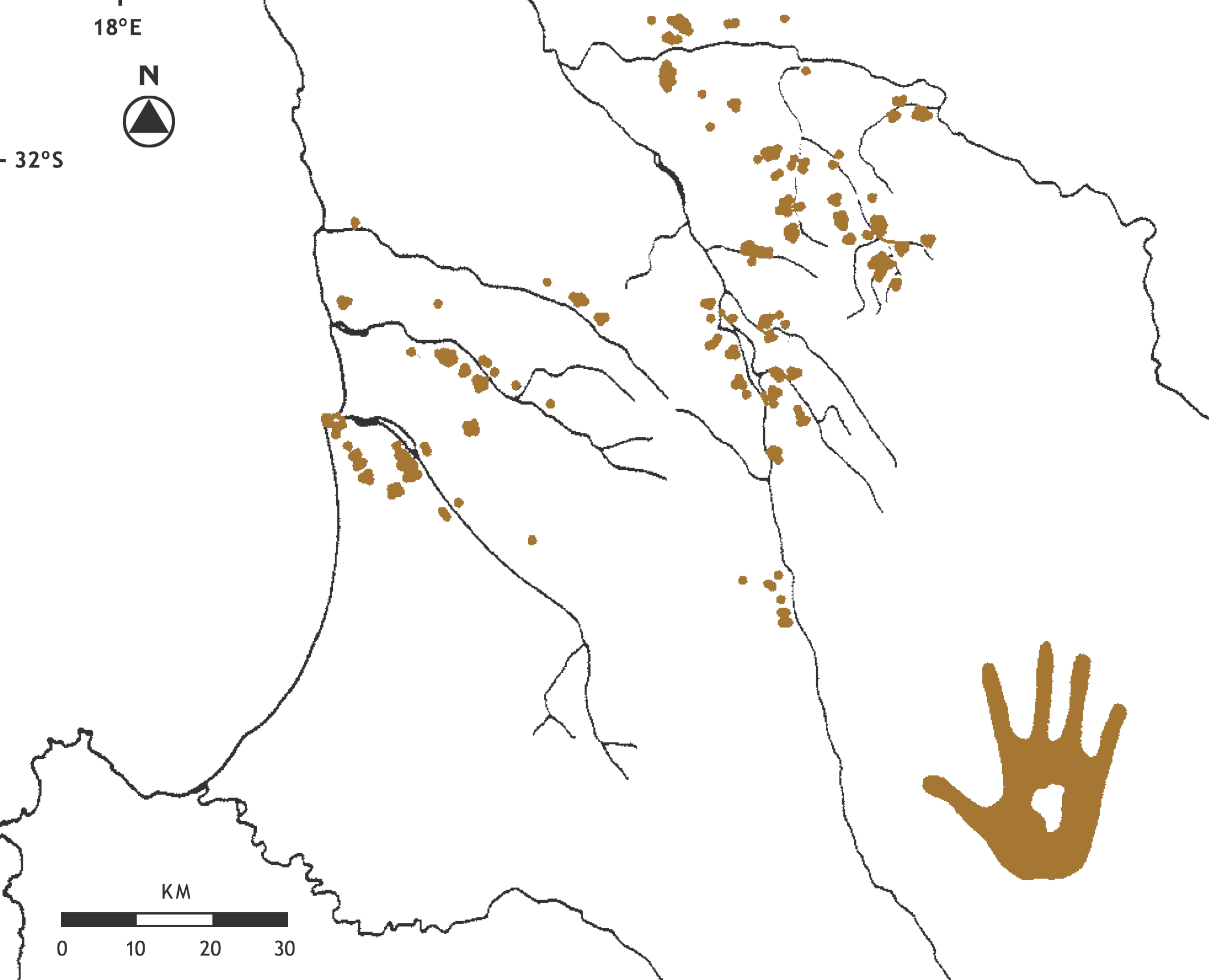

The distribution of hand prints in the south-western Cape has been remarked upon several times before (for example: Willcox 1959; Maggs 1967; Rudner & Rudner 1970; Manhire et al. 1983; van Rijssen 1984; Yates et al. 1994). This current appraisal is based on a much larger number of observations and incorporates all the material accumulated by the Spatial Archaeology Research Unit. As can be seen in Fig. 3, plain hand prints are found all the way across the research area from the coast to the mountains. Their distribution virtually mirrors the distribution of rock paintings across the landscape and there is no area with a significant number of paintings that does not also have plain hand prints.

In contrast, the decorated form is common at the coast and in the Sandveld near the coast but is completely absent from the Olifants River Valley and from the mountain ranges on either side of the Olifants River (Fig. 4). The decorated form reappears again in the northern and eastern fringes of the mountains along with an interesting variation. The decorated form here has examples similar to the coastal set but also includes a hand print with a different form of decoration. Both decorated types are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Map of the south-western Cape showing the distribution of sites with plain hand prints.

The numbers of sites with hand prints in the Sandveld and the mountains are shown in Table 1. The figures at the top of the table show the total number of rock art sites recorded in the respective areas with sites with hand prints expressed as a percentage of these totals. Although the frequency of sites with hand prints is virtually the same in both areas, the decorated form is far more common in the Sandveld.

| Table 1 | ||

| Comparison of sites with hand prints in the Sandveld and Mountains.The figures in brackets show the number of hand print sites as a percentage of the total number of rock art sites in each area | ||

| Rock Art Detail | Sandveld | Mountains |

| Total rock art sites | 517 | 1074 |

| Sites with hand prints | 79 (15,3%) | 168(15,6%) |

| Sites with plain hand prints | 76 (14,7%) | 164 (15,3%) |

| Sites with decorated hand prints | 35 (6,8%) | 19 (1,8%) |

Several authors (Willcox 1959; Maggs 1967; Rudner & Rudner 1970 for example) have commented on the small size of hand prints in the south-westernCape and reflected on what this might mean regarding the stature of the painters. Willcox (1959) took this observation a stage further by attempting to correlate hand length with body height of various Khoisan groups. Maggs (1967), using the method advocated by Willcox (1959), measured a number of hand prints from a sample area in the south-western Cape. He concluded that not only were the people who made the hand prints small in stature but that some hand prints may have been the work of children. This present case study was in part motivated by the work of Henneberg & Mathers (1994) who published the results of a study of school pupils from the Little Karoo in which they outlined procedures for reconstructing body size and possibly the age and sex of individuals from their hand prints. These authors based their conclusions on a study of 196 children and youths, aged 5 to 20 years (71 boys and 125 girls), from three schools at Calitzdorp in the Little Karoo. All the children involved in the study are partly descended from indigenous populations that once lived in the area.

The method used by Henneberg & Mathers(1994) was to cover the palmar side of each pupil's hand with thick water-based paint and print the hand on a sheet of paper. The subject's sex, age and height were also recorded.The painting of right or left hands was the choice of the individual pupils. From a total of 196 pupils there were 144 prints of right hands and 52 of left hands. Henneberg & Mathers (1994) note that regressions derived for the right and the left hands separately did not differ significantly. Similarly, there was little difference between regressions derived separately for the body height and age of boys and girls. The regressions used, therefore, were derived from the combined sample and, based as they were on relatively large samples, yielded accurate estimates of height and age. Since the sex of the people who left the hand prints in the rock shelters is unknown, the use of regressions derived from the entire sample is further justified. The equations used for reconstructing body height and age from hand length are shown in Table2 along with the standard errors of the estimates.

| Table 2 | ||

| Equations for reconstructing body height and age from hand print measurements.Hand length (L) and standard errors of estimates (in parentheses) in mm. The reconstructed body height (H) in mm and the age (A) in years (after Henneberg & Mathers 1994) | ||

| Independenvt variable | r | Reduced major axis |

| Hand length (L) | 0,94 | H = 8,86L + 52,73 (∓ 4,08) |

| Hand length (L) | 0,85 | A = 0,19L - 16,12 (∓ 0,14) |

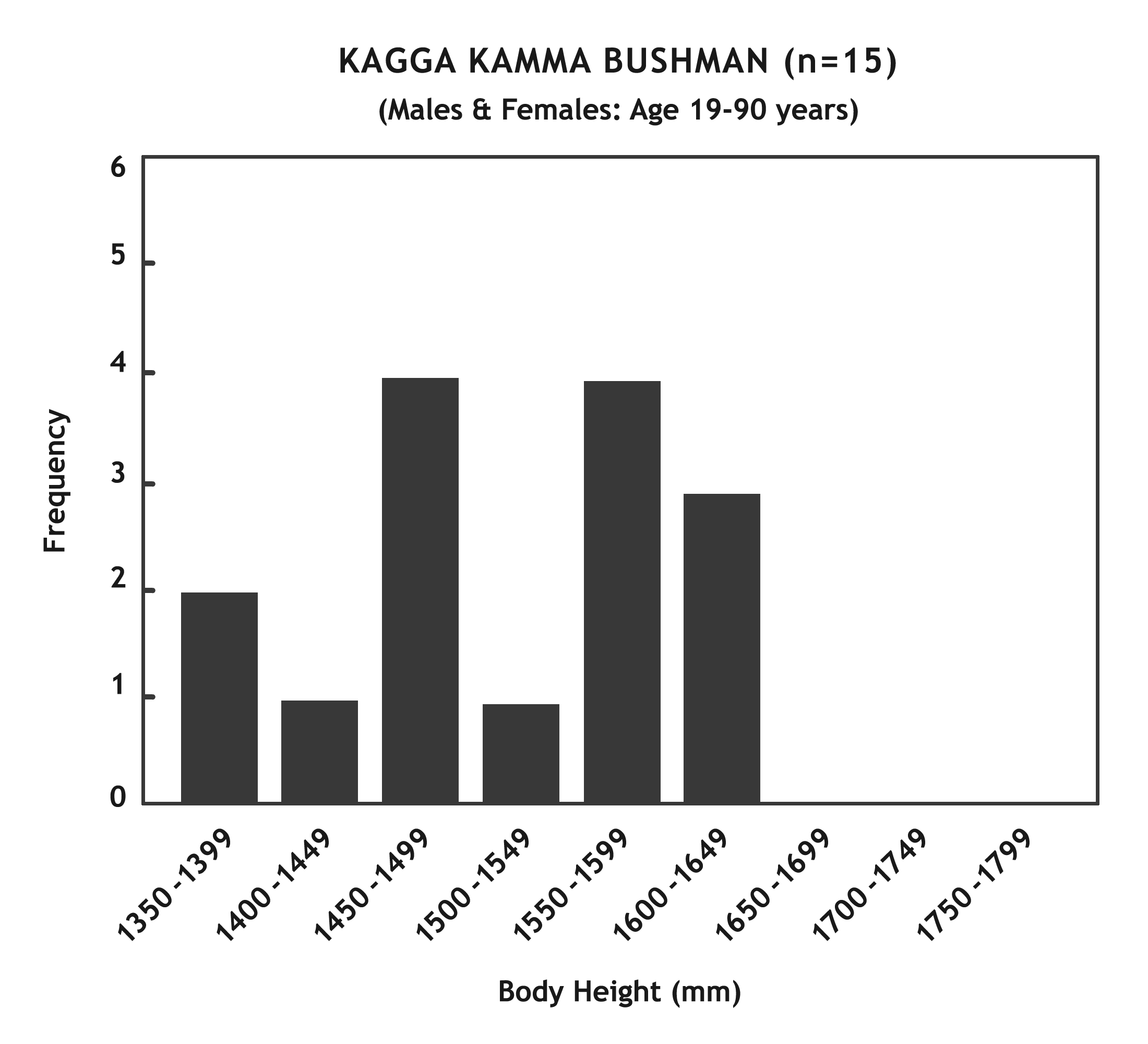

The most important question that arises from using the formulae derived by Henneberg & Mathers (1994) to reconstruct body height from hand prints is whether results from school children in the Little Karoo are applicable to precolonial populations in the south-western Cape? Although the authors argue that their equations can be applied to other regions, they also note that "it would obviously be advantageous to use measurements of living populations as close to the ancient printers as possible" (Henneberg & Mathers 1994:496). Although people descended from the hand print makers may still exist in the south-western Cape we have no way of identifying them. There are, however a group of San living in the south-western Cape at Kagga Kammaand it was to these people that we turned for assistance.

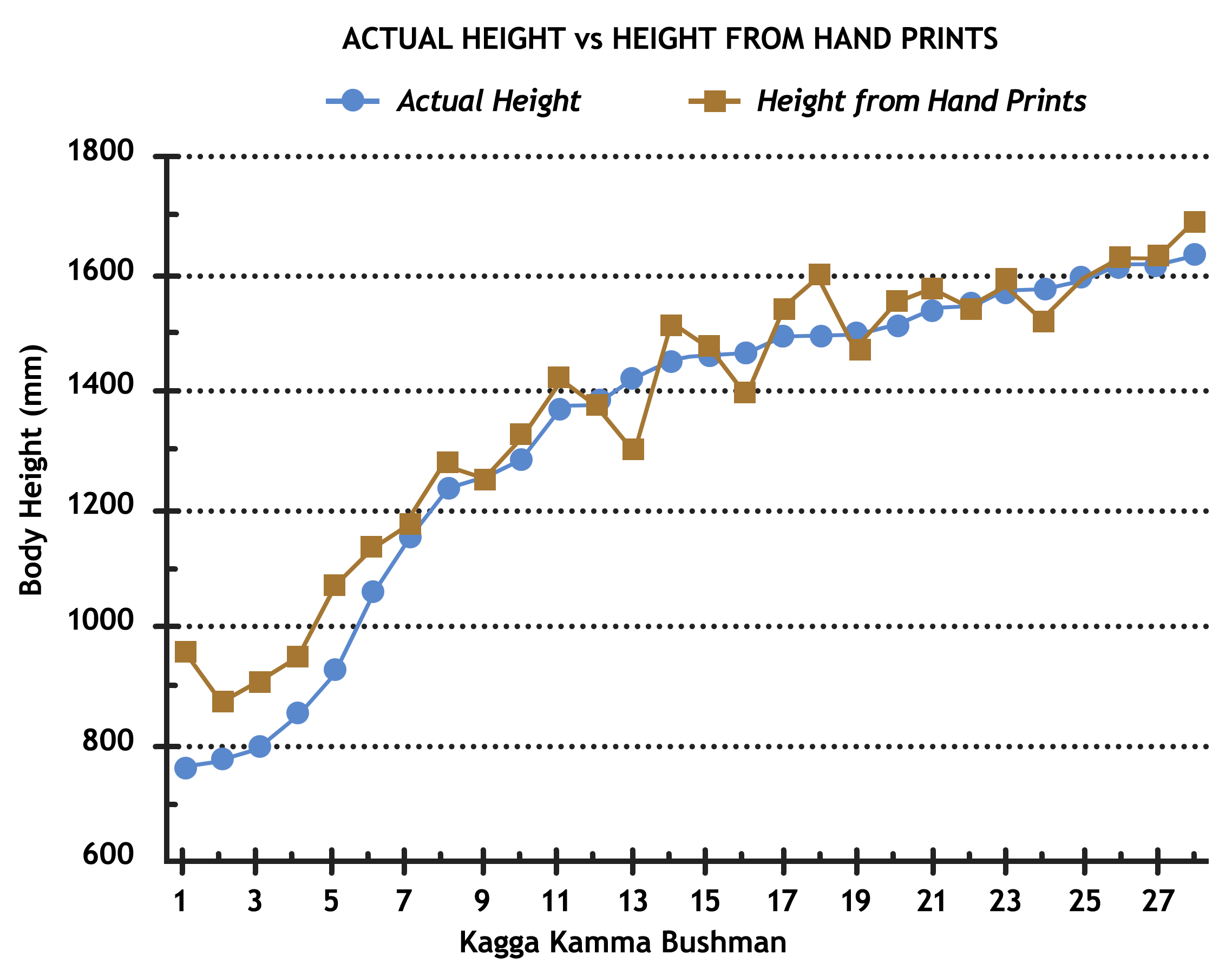

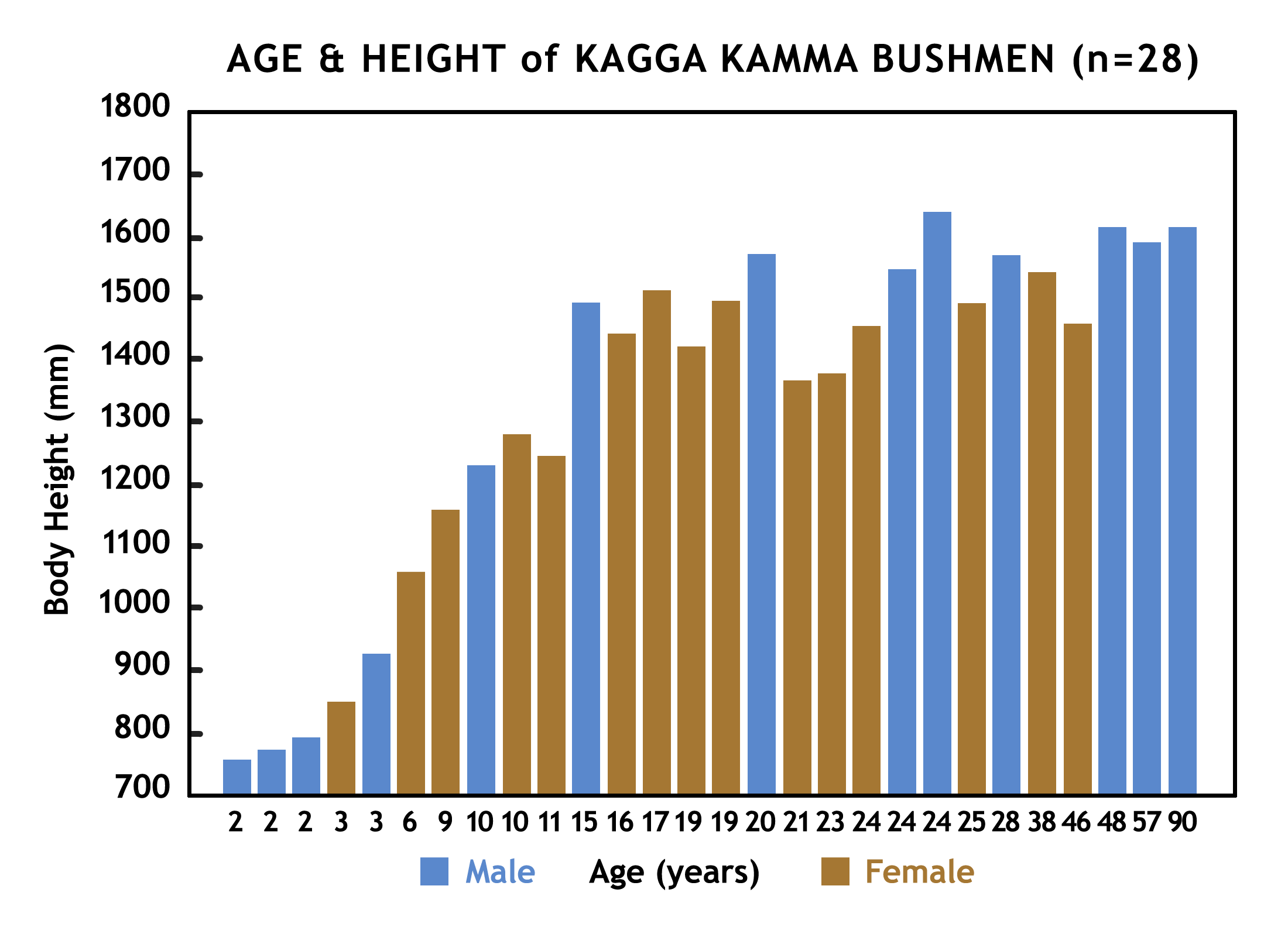

Kagga Kamma Bushmen. Comparison of actual body heights of with body heights reconstructed from handprints.

At the time when the measurements were taken there were 28 people living at Kagga Kamma. These included 13 males and 15 females, with ages ranging from 2 to 90 years. Hand prints were made using poster paint on sheets of paper and body height was measured using an anthropometer. The difficulty of using this instrument in the field in what were less than ideal conditions probably created some errors in the height measurements.This was particularly evident when trying to measure accurately the height of the very young children. The results are presented as a graph in Fig. 5. The first five measurements refer to the children of less than five years old and may be discounted due to the inherent difficulties described above. The remaining set of measurements show a reasonable correspondence although there is a tendency for the reconstructed height to exceed the actual height. Although some of the discrepancies are quite marked, for the group as a whole the handprint height exceeds the actual height by an average of only 16 mm.

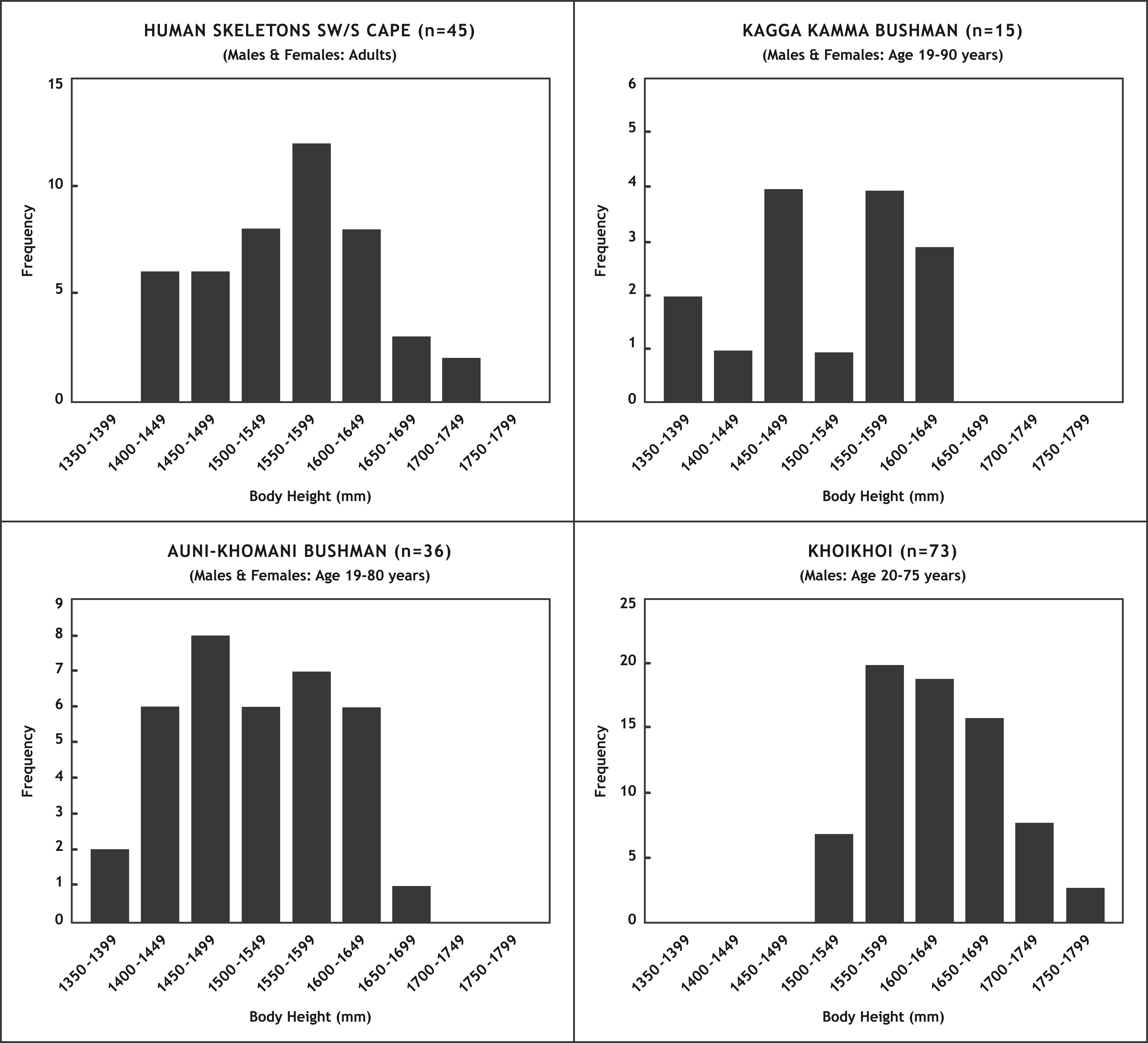

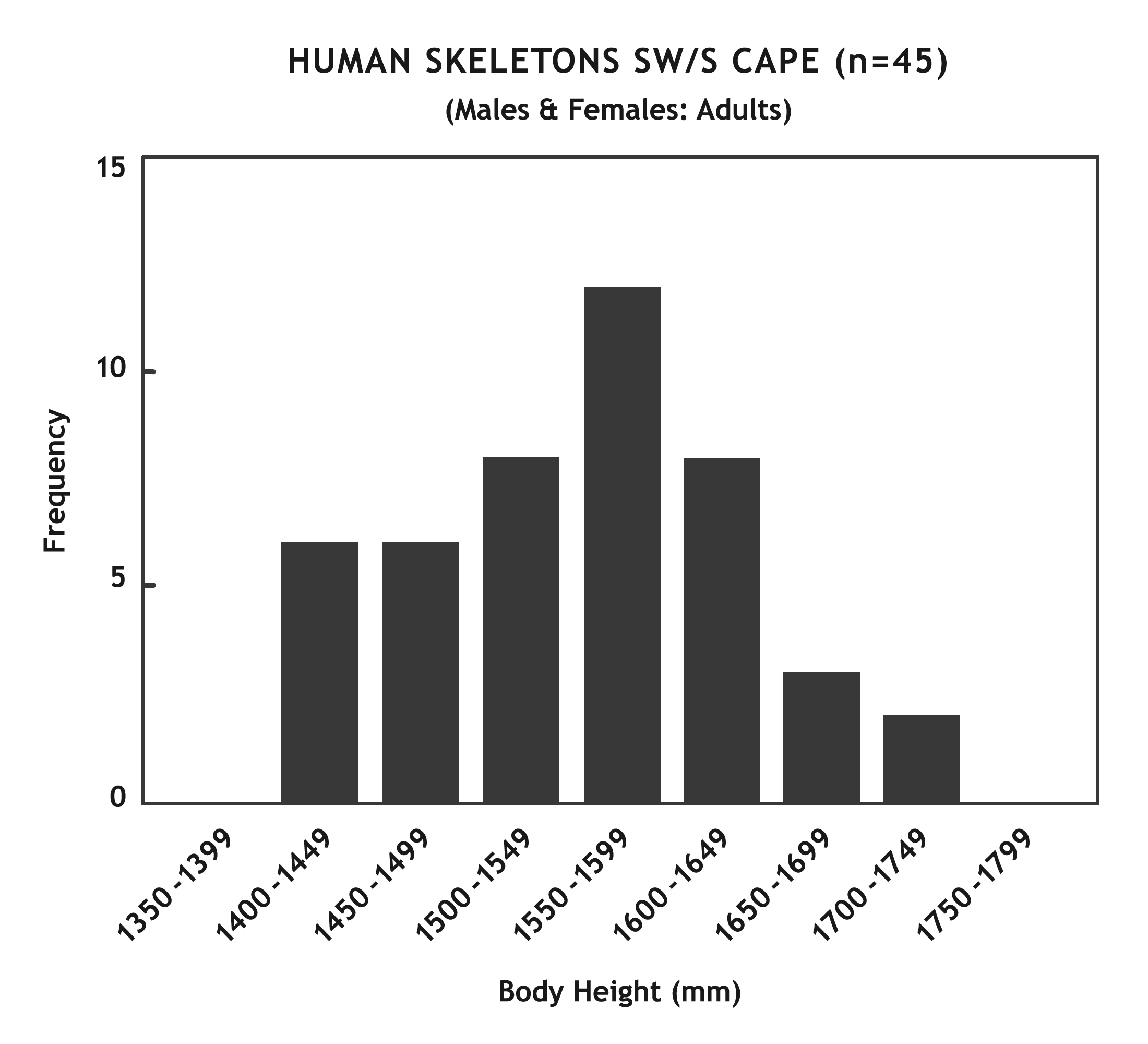

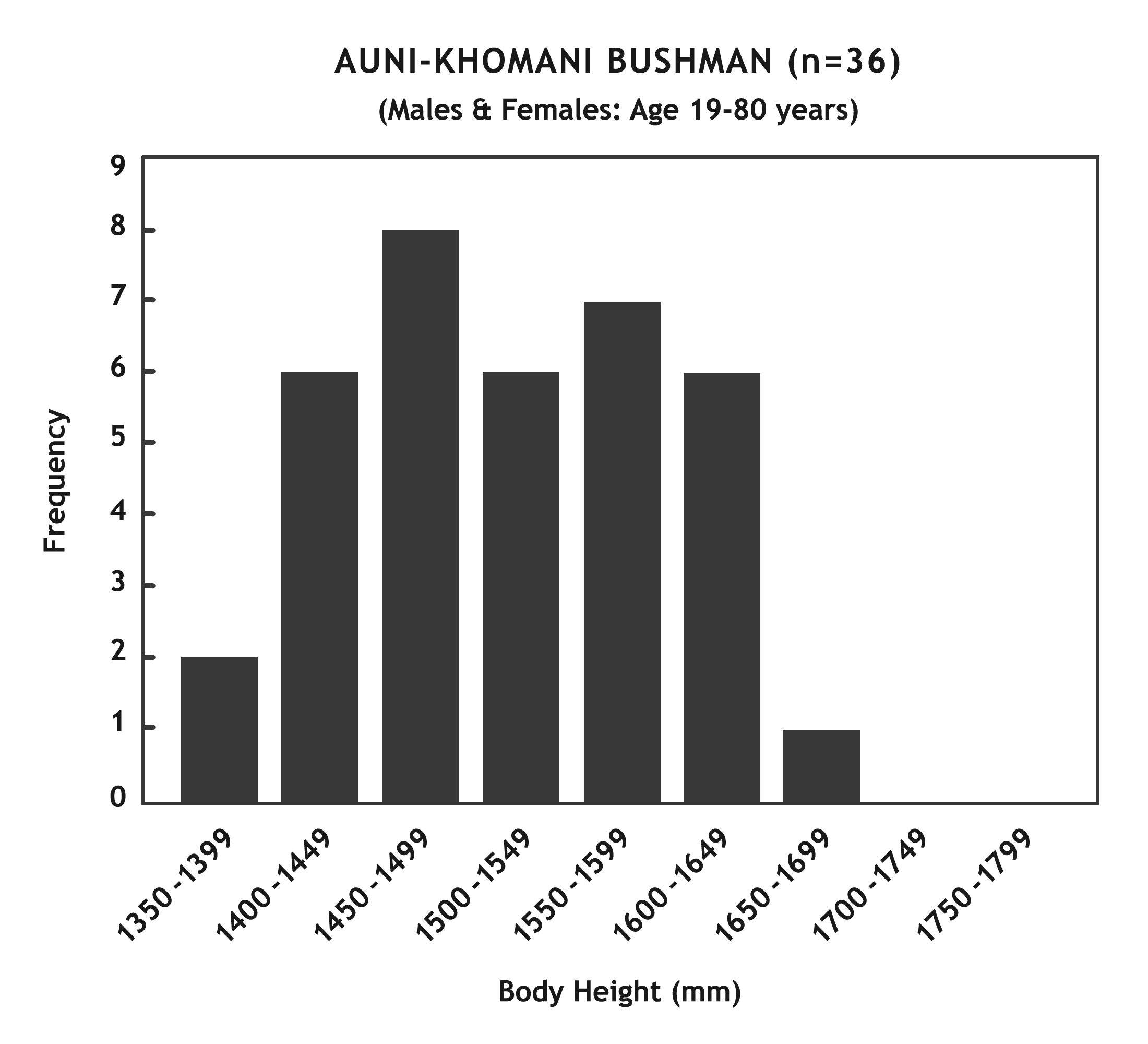

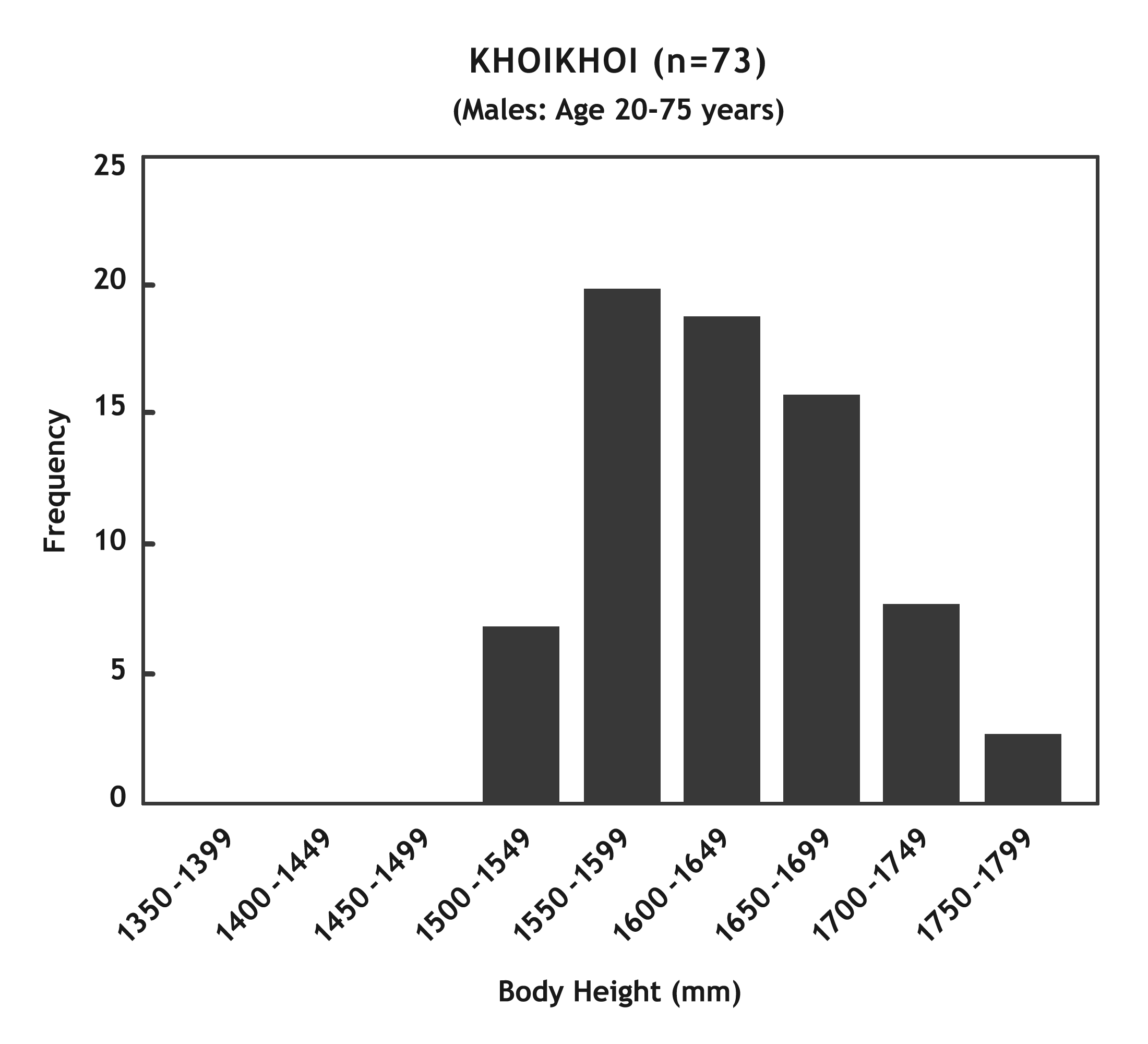

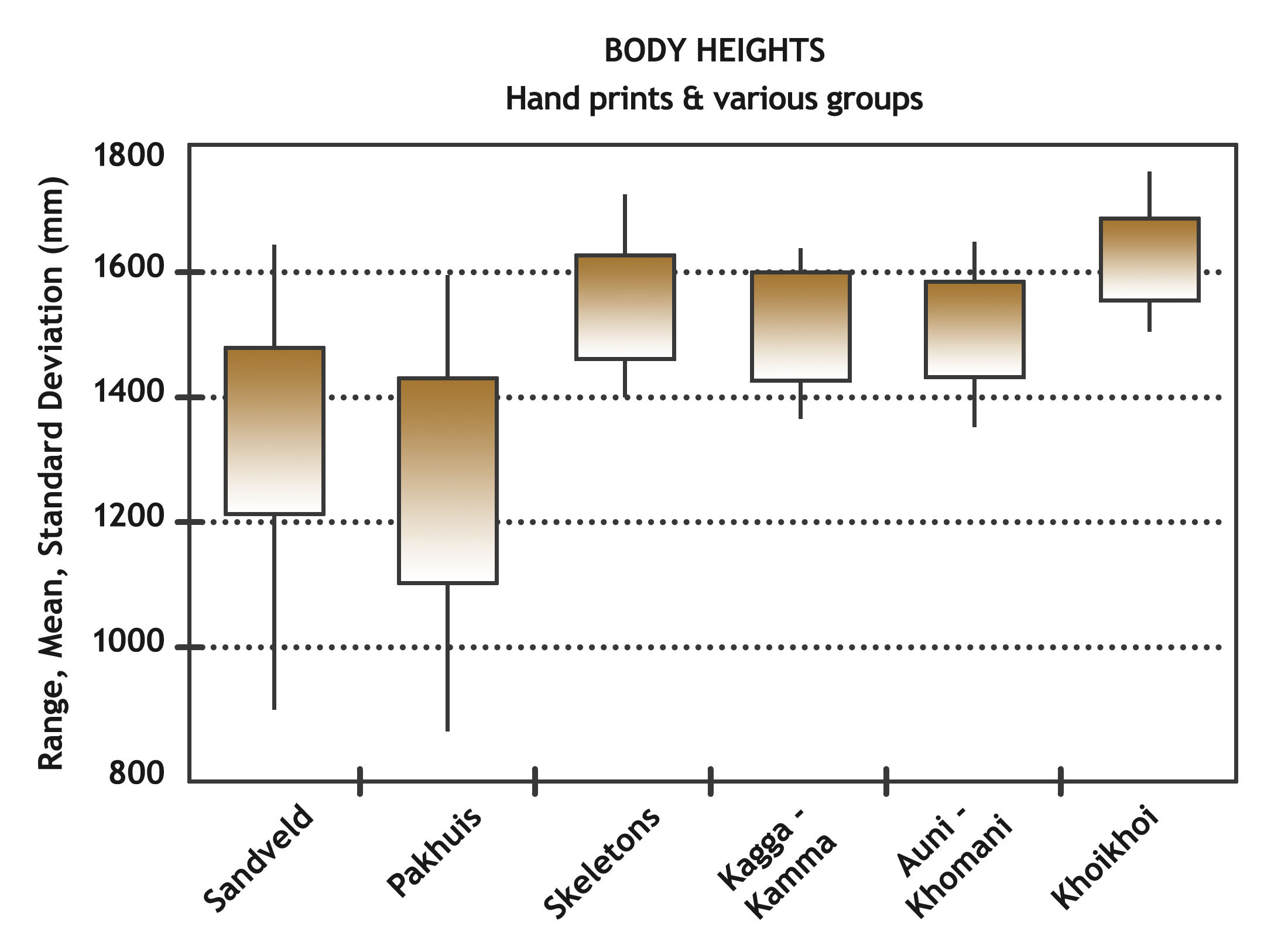

Before presenting the results of a sample of handprint measurements from the south-westernCape, it would be useful to examine some of the existing records of stature of Khoisan-populations. The body heights of four different groups are shown in Fig. 6. The first of these deals with skeletal material recovered from excavations, the second group is the Kagga Kamma San mentioned above and the last two are from ethnographic sources. Although none of these groups are particularly satisfactory as comparative material, they do provide some of the few available measurements against which the calculated estimates of body height from hand prints can be judged.

The first group of measurements in Fig. 6 are reconstructions of body height based on skeletal remains as described by Wilson (1990). Of the 45 skeletons measured, 38 were recovered from the south-westernCape, mostly in coastal locations, whilst the remaining seven individuals were from Byneskranskop and Oakhurst in the southern Cape. Both males and females are present in the set, the criteria governing selection being that all theskeletons were dated adults, complete enough for sex and height to be determined.Wilson (1990) obtained estimates of the living stature of the skeletons using the method advocated by Lundy & Feldesman (1989) for converting femur length to stature.

With the exception of a single female from Elands Bay, none of the skeletons come from the same locality as the hand prints discussed below. All the hand prints are from the Sandveld and the Cedarberg whereas the skeletons were recovered from a wide area ranging from the south-western to the southern Cape. They also range widely through time with the earliest dated to 9100 ± 90 BP (Pta-3724) and the latest to 620 ± 30 (Pta-4189) years ago BP. (Wilson 1990). The question of the age of the hand prints is dealt with more fully in the discussion but suffice to say that many of the skeletons are beyond the time range believed applicable to hand prints in the south-western Cape. Notwithstanding these complications, the skeletons are presumed to represent the same gene pool as the hand print makers and, as such, are among the best available references for comparative statures.It should also be noted that Wilson and Lundy (1994:2), after having examined the skeletons, concluded that "despite some evidence for diachronic change, the statures of the prehistoric San were similar to those of the modernSan sample".The information on the body heights of the excavated skeletons, along with the other groups dealt with in this section, is summarised in Table 3.

The second group in Fig.6 are the Kagga Kamma San. For ease of comparison with the other groups only adults of age 19 years and over have been included. Summary statistics of body height are shown in Table 3.

The third group shown in Fig.6 are the /'Auni- ≠Khomani from the southern Kalahari who were the subject of an intensive investigation by the anatomist Raymond Dart in the 1930s. Most of the individuals were of the ≠Khomani 'tribe' but also included the linguistically related !'Auni with whom the ≠Khomani had intermarried (Barnard 1992). A total of 77 measured by Dart (1937). Of these, 36 were adult males and females whose body heights are represented in Fig. 6.

The final group in Fig. 6 are a group of 73 adult males from Namibia referred to by Schultze (1928) as 'Hottentots'. Wilson (1990) shows that the majority of Schultze's sample group were members of various subdivisions of the Nama with smaller numbers of Oorlam and Griqua. Wilson (1990) also notes that although this 'Khoikhoi' group is best understood as genetically hybridised, it is the only 'Khoikhoi-like' sample for which information is available.

| Table 3 | ||||

| Summary data for body heights of skeletons, Kagga Kamma San, /'Auni-≠Khomani and Khoikhoi. All the individualsare adults (m = male, f= female, s.d. standard deviation). | ||||

| Group | No. | Range (mm) | Mean (mm) | s.d. (mm) |

| Skeletons (m+f) | 45 | 1404 - 1723 | 1547 | 80,2 |

| Kagga Kamma (m+f) | 15 | 1368 - 1640 | 1517 | 83,6 |

| /'Auni- ≠Khomani (m+f) | 36 | 1356 - 1648 | 1513 | 74,1 |

| Khoikhoi (m) | 73 | 1505 - 1761 | 1624 | 62,2 |

The fieldwork program consisted of systematically recording and measuring hand prints at sites in the south-western Cape. Initially three measurements were taken of each print:total hand length, palm length and subdigital width, according to the method described by Henneberg & Mathers (1994). In practice, however, the latter two measurements were found to be difficult to obtain accurately from a painted print and only the total length was recorded. This was measured from the edge of the tip of the middle finger to the distal flexion crease on the wrist.

Another problem encountered was that many hand prints were either incomplete or too faint for accurate measurements to be taken. In order to obtain a consistent sample, only prints with the fingertips and 'heel' of the palm clearly visible were measured.The decorated prints tended to be the most troublesome as in most examples either the fingers were not clearly demarcated or only the decorated palm was printed on the wall.

Most of the fieldwork was concentrated in two specific areas as shown in Table 4. A sample of 180 prints was obtained from the Sandveld with the mountains being represented by a sample of 202 prints from the area of the Pakhuis Pass (see Fig. 1 for locations). This reflects a deliberate strategy to sample from two geographically distinct regions, which also delineate a major separation in terms of the distribution of handprints.

| Table 4 | |||||

| Summary of data for body heights reconstructed from hand prints (s.d. = standard deviation). | |||||

| Area | No. of sites | No. of HPs | Range (mm) | Mean (mm) | s.d. (mm) |

| Sandveld | 22 | 180 | 903 - 1612 | 1348 | 132,1 |

| Pakhuis | 27 | 202 | 868 - 1594 | 1269 | 162,6 |

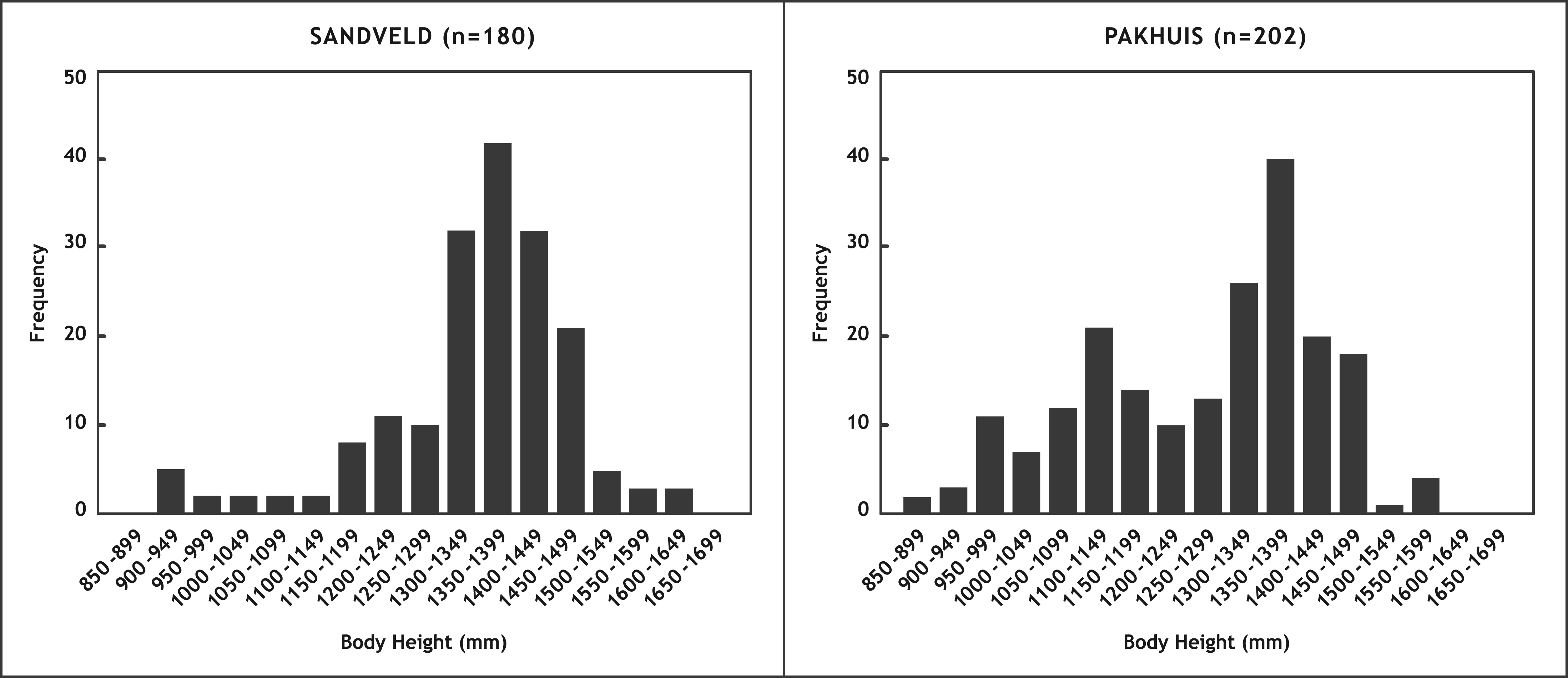

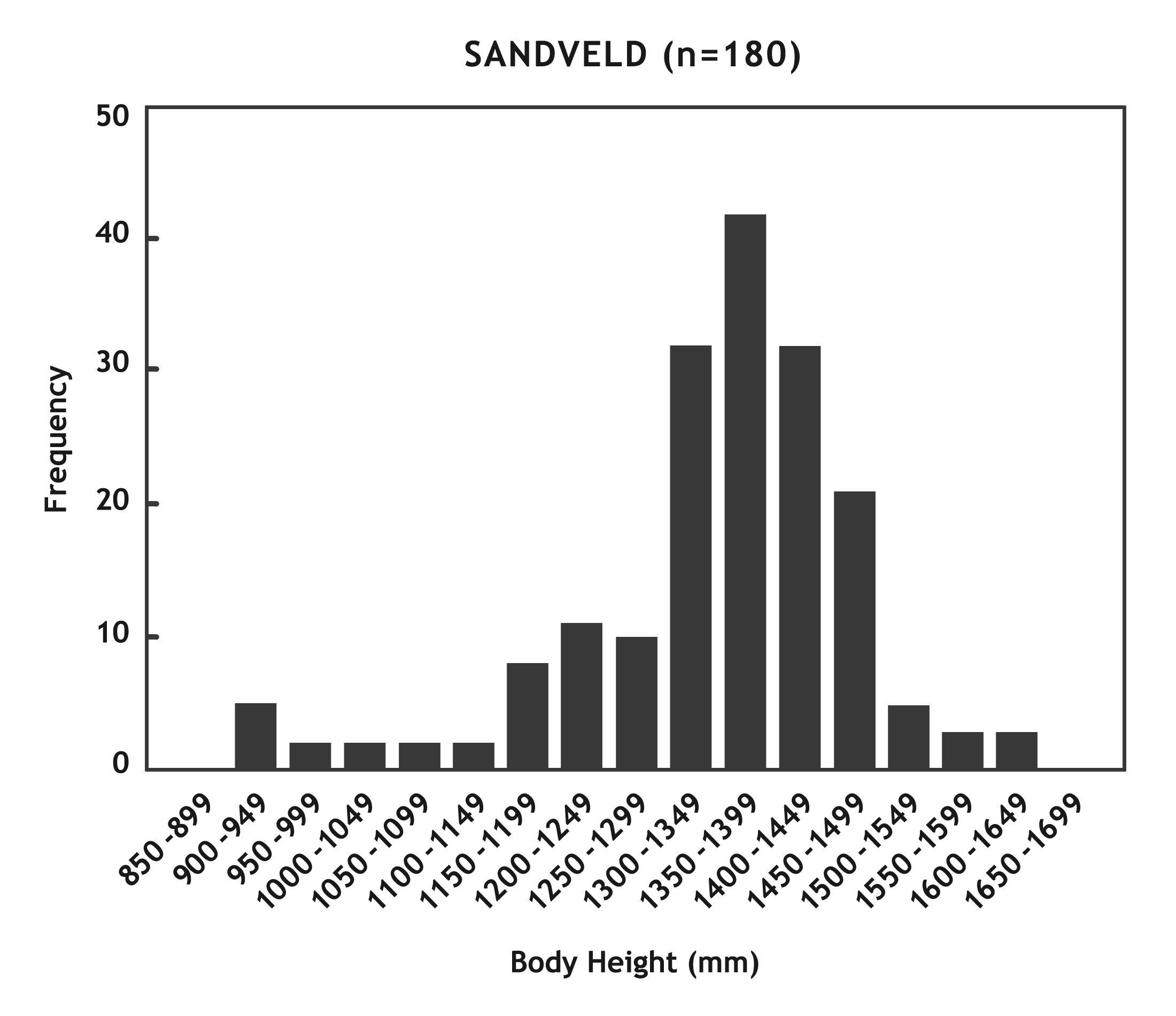

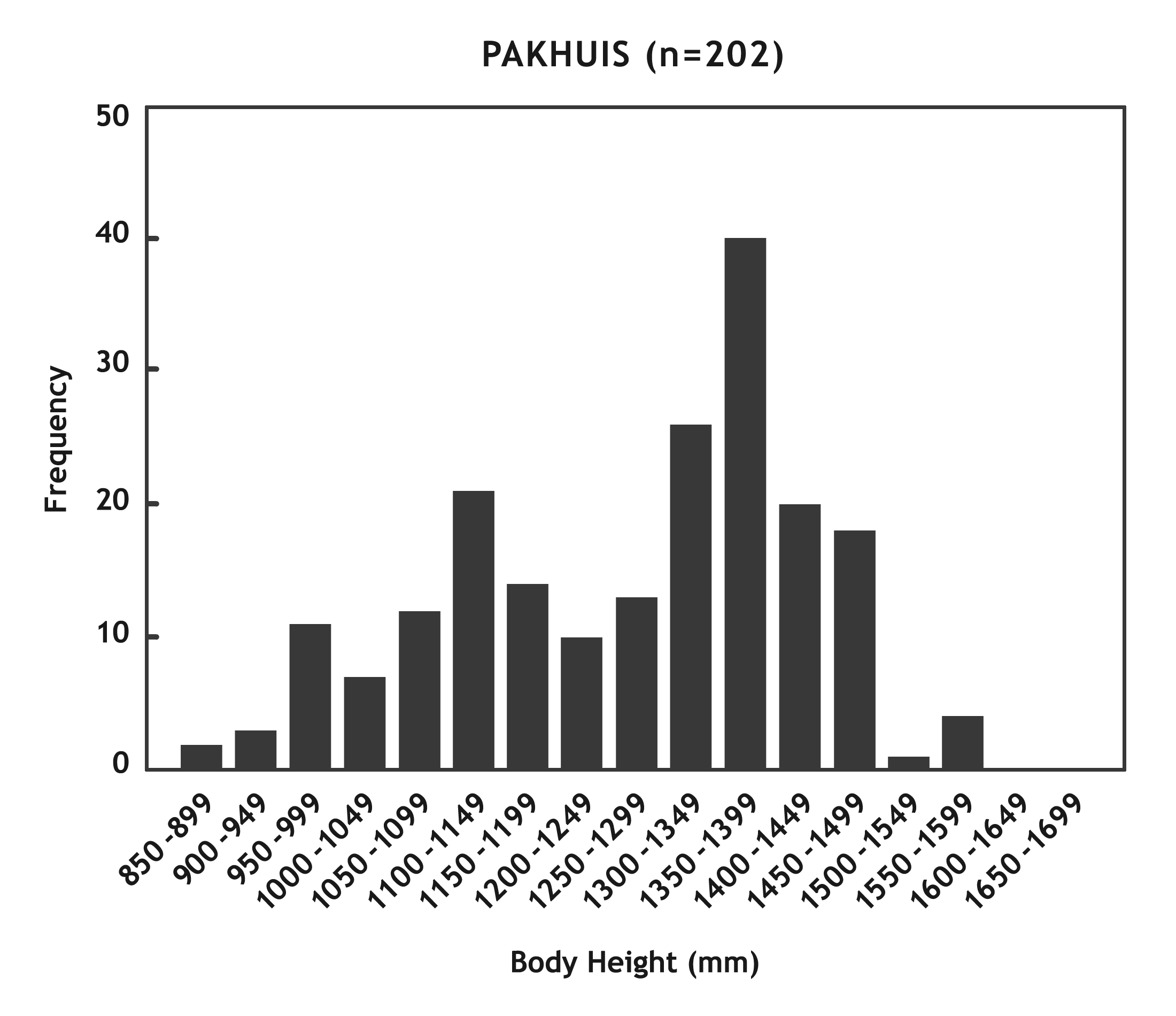

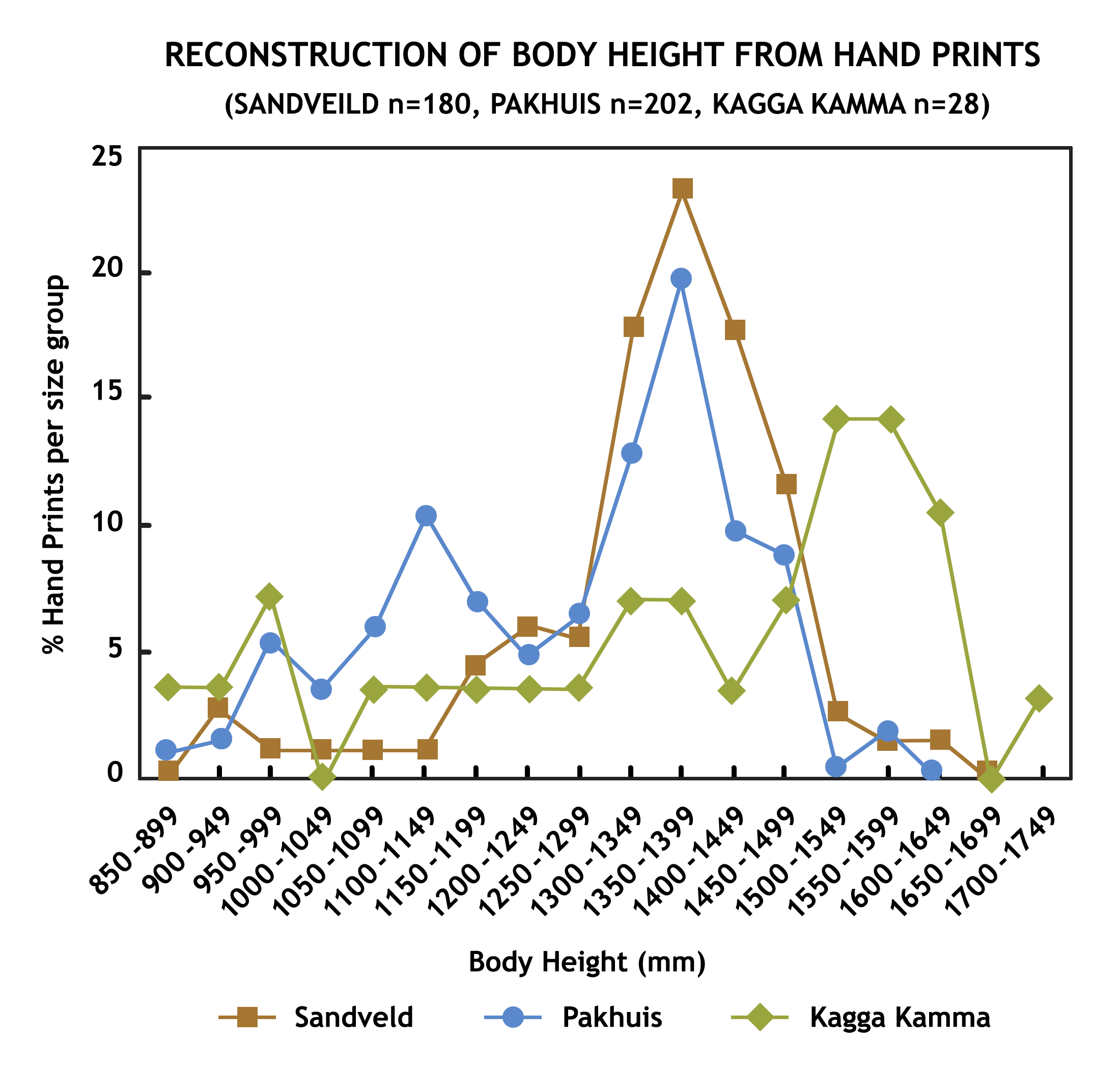

Body heights were reconstructed for the south-western Cape hand print sample using the regressions of Henneberg & Mathers (1994). The reconstructions for the two different areas are presented graphically in Fig. 7 with the data summarised in Table 4. The range is similar in both areas but with the Pakhuis showing a shift towards smaller body size. This is also reflected in the means. However, as the samples are not normally distributed, the mode is probably a better indicator than the mean. The Sandveld sample portrays a basically unimodal distribution with a single mode at 1 350 - 1 399 mm. In contrast, the Pakhuis sample has a bimodal tendency with a minor mode at 1 100-1 1149 mm and a major mode at 1 350 - 1 399 mm. This has implications for the age reconstruction discussed below.

Reconstruction of body heights from hand prints from the Sandveld.

It is now possible to make a more meaningful interpretation of the hand print measurements from the south-western Cape. The following two points are, however, particularly relevant. Firstly, it has been shown from the set of observations obtained from the Kagga Kamma San that the formulae derived by Henneberg & Mathers (1994) can be applied with some confidence to hand prints from the south-western Cape. Secondly, the set of recorded statures from the various groups presented above, although not entirely satisfactory, do provide a useful framework for evaluating the hand print sample.

| Table 5 | |||||

| Matrix of level of significance for body heights from Kolmogorov-Smirnov two sample test. Samples are from hand prints (see Table 4 for details) and from ethnographic sources (see Table 3 for details). 0 = no significant difference at 0,05 level, S = significant difference at 0,05 level, HS = 0,01 level, VHS = 0,001 level. | |||||

| Pakhuis | Skeletons | Kagga Kamma | Auni Khomani | Khoikhoi | |

| VHS | VHS | VHS | VHS | VHS | Sandveld |

| VHS | VHS | VHS | VHS | Pakhuis | |

| 0 | 0 | HS | Skeletons | ||

| 0 | HS | Kagga Kamma | |||

| VHS | Auni Khomani | ||||

In Table 5, the hand print samples are compared with the skeletons and the various ethnographic samples using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two sample test (Shennan 1988). Looking at the hand print measurements first, the test shows that the Pakhuis sample is significantly different from the hand print sample from the Sandveld. More interestingly, however, both the hand print samples are significantly different from all of the comparative samples. This means that the body heights of the people who made the hand prints are not the same as the body heights of the skeletons and the other groups which make up the comparative sample. It is worth noting here that comparative groups are all composed of adults whilst the ages of the hand print makers are unknown.

Comparison of body heights from hand prints with body heights from various groups using range, mean and standard deviation (for summary of data see tables 3 and 4).

Fig. 8 also shows that the majority of the body heights from the hand print sample fall outside the range of the Kagga Kamma adults.The Pakhuis sample is the most pronounced with 66.8% of reconstructed body heights falling below the range of the Kagga Kamma adults. Likewise, by far the greater number of heights from the hand print samples are smaller in size than Schultze's 'Khoikhoi' group.

The most extreme example is from the Pakhuis where 97.5% of the reconstructed body heights fall below the range of the 'Khoikhoi' sample. This means that it is un- likely that the hand prints were made by Khoi adults although it must be remembered that Schultze's sample as composed entirely of males and, furthermore, the group was in all probability of mixed origin.

The four comparative samples presented above include only individuals of adult age. The age of the hand print makers is obviously one of the unknown factors but it is significant that the majority of all the reconstructed body heights fall well below the range of the comparative samples. This strongly suggests we are dealing with a hand print sample comprising individuals mainly below adult age. It must also be remembered that the application of Henneberg & Mathers (1994) formula produced body heights that averaged 16 mm less than the heights derived from hand prints. This implies that the hand print makers may be even smaller than shown in the reconstructions.

Comparison of body heights of Kagga Kamma Bushmen with body heights reconstructed from hand prints from the Sandveld and Pakhuis area.

To go one stage further and obtain an estimationof the actual age in years of the hand print makers is a more difficult challenge. The situation is further complicated by the fact that we have no idea as to whether the hand prints were done by males, females or a combination of both. Two approaches to solving the question of age are used here although neither is problem free. The first is to apply the equations of Henneberg & Mathers (1994) for reconstructing age from hand print size. The second is to use the known body heights and ages of the Kagga Kamma San.

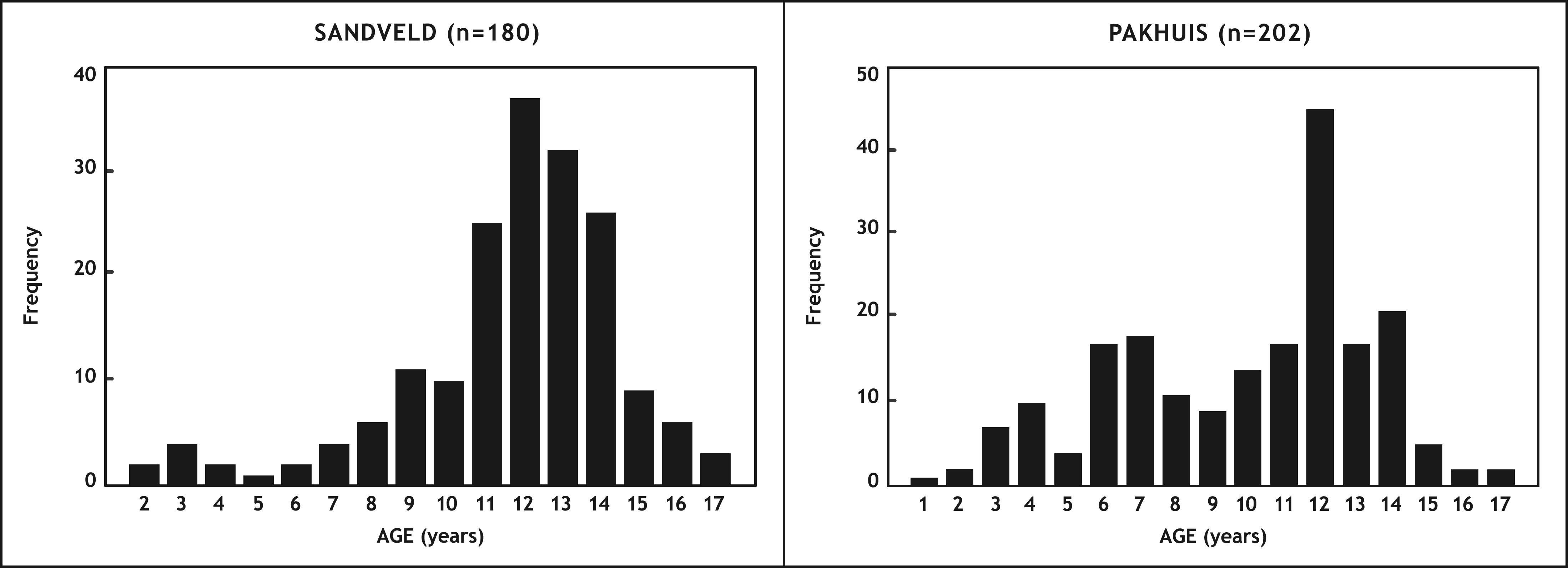

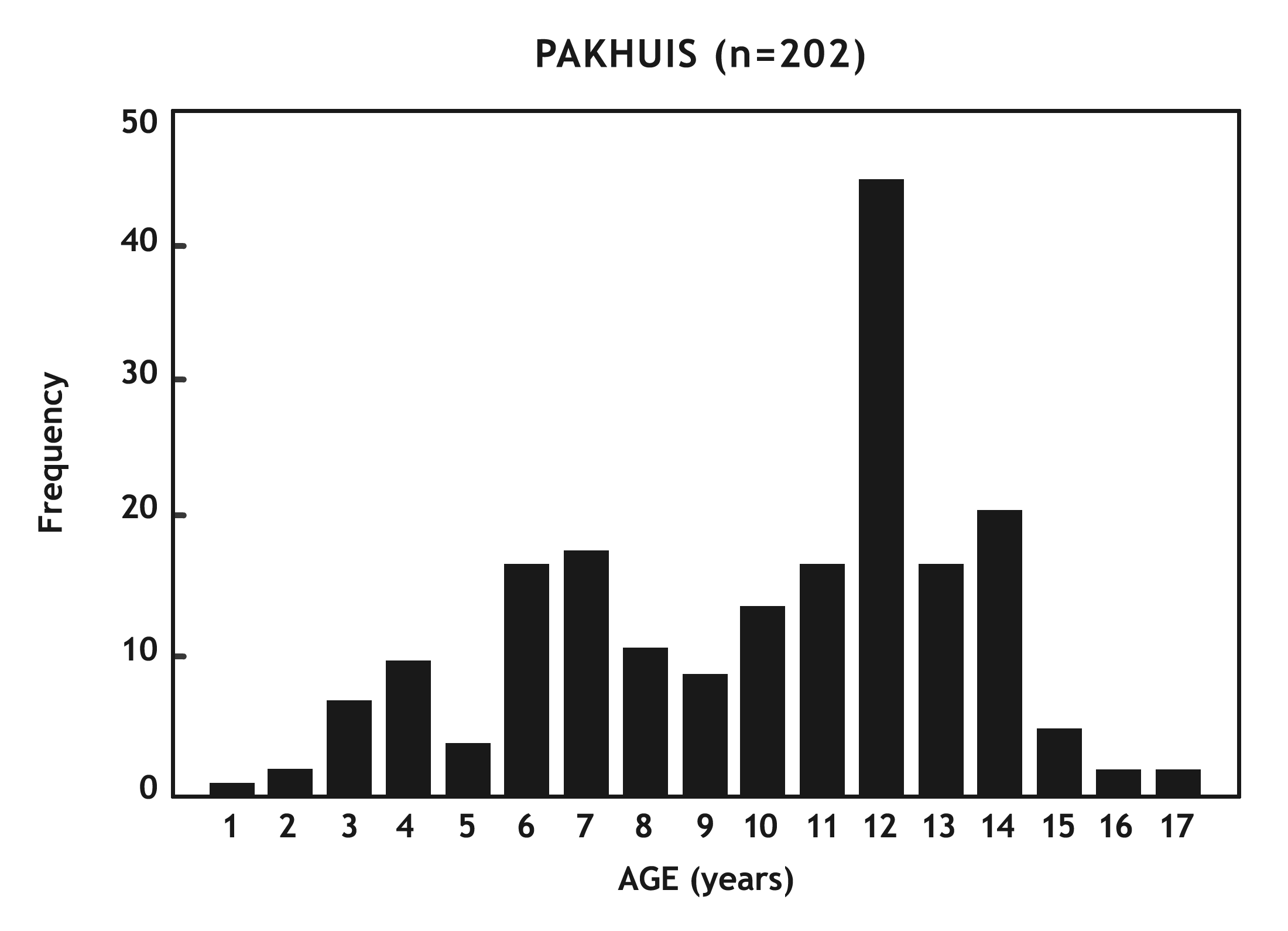

The results of applying Henneberg & Mathers (1994) equations for reconstructing age from hand prints are shown in Fig. 10. As would be expected, the shapes of the bar graphs resemble those for body height (Fig. 7). The Sandveld has a peak at age 12 years whilst the Pakhuis has a similar peak at 12 years and a smaller peak of 6-7 years. Whilst these results may look convincing a number of reservations must be expressed. Firstly there is the inherent difficulty of applying regressions derived from present day school children from the Little Karoo to past populations in the south-western Cape. The second is that none of the hand print derived ages exceed 17 years, which, as discussed below, may not be an accurate reflection of the age range.

Reconstruction of age of individuals from hand prints from the Sandveld area.

In Fig. 11 the measured body heights of the whole Kagga Kamma group are plotted against their known ages. Although the sample is far too small to draw any definite conclusions a number f interesting points emerge. First, the height increases fairly regularly with age up until the age of about 10 years. Above age 10 years there is considerable variation in height between males and females of roughly similar ages. Secondly, there is very little increase in height above 17 years which is presumably the age that adult height is reached. This helps to explain why the graphs derived from Henneberg & Mathers (1994) regressions failed to produce any ages above 17 years. In this case a reading of 17 years would best be interpreted as an adult of 17 years or over.

Despite all these complications there is a reasonable degree of correspondence between the ages suggested by the hand print reconstructions and the age and height of the Kagga Kamma San. Using the reconstructed body heights shown in Fig. 9 in conjunction with the other evidence presented above it is possible to draw the following conclusions. The majority of the hand print makers were less than 17 years of age. The largest number of hand prints were probably done either by boys between 12 to 14 years of age PAKHUIS (n=202) or girls between 14 to 16 years of age. In addition, the sample from the Pakhuis includes a smaller concentration of hand prints by boys and/or girls of about 6 to 9 years old.

The final question to be addressed is the interesting, if intractable problem, of whether males, females, or both were involved in the making of hand prints. One possible clue is the fact that adult females are, on average, smaller than adult males. This has been consistently demonstrated by studies of various San populations during the early part of this century (Seiner 1912, 1913; Bleek 1927; Lebzelter 1931; Dart 1937) and more recently among groups in the Kalahari (Wells 1952; Truswell & Hansen 1976). In addition, there is a degree of variation in stature between populations with southern San tending to be shorter in stature than northern and central San (Clark 1959; Tobias 1962, 1972). There is also evidence (Tobias 1962, 1972) of a general increase in stature amongst San during this century. Furthermore, there has been an accentuation of sexual dimorphism of stature with males showing a greater in- crease in height than females (Tobias 1962, 1972). This has resulted in a mean difference of 96 mm between adult males and females in populations measured before the mid- 1950s (Tobias 1962) as compared to a mean difference of 108 mm in later Kalahari groups (Truswell & Hansen 1976).

Sexual dimorphism was also present in the admittedly small sample of skeletons described by Wilson (1990). It is, therefore, fairly safe to assume it existed in the indigenous populations responsible for the hand prints and that the mean height difference between adult males and females was probably in the region of 100mm. This would not help to separate males and females in the middle of the stature range, as sub-adult males would have a similar height sig- nature to adult females, but it does have implications for the upper end of the stature range. If the hand prints were done by San people, it can be stated with some certainty that the large hand prints, at the top end of the size range, were done by males as the reconstructed statures fall outside the height range of contemporary San females. This argument becomes more persuasive considering possible genetic hybridisation of modem San populations (Tobias 1962) as well as the general increase in size discussed above.

Hand prints as a component of the rock art record

Hand printing on rock surfaces is a world wide phenomenon not restricted to any one time or place. As such there can be no single or simple reason why people make hand prints. This is borne out by a number of explicit accounts recorded from different parts of the globe. In the American south-west, for example, modem Pueblo Indians use hand prints for purposes of identification and individual supplicants leave prints of their hands in sacred places (Ellis & Hammack 1968; Schaafsma 1980). Alternatively, in north-western Australia young boys undergoing initiation rites leave a negative prints of their hands at sites set aside for this purpose (Trezise 1969). One thing these two examples have in common is that in each case a hand print equates to an individual person.

Unfortunately there is no explicit reference to hand printing in modem San ethnography such as that recorded by Bleek and Lloyd (Lloyd 1911) and Orpen (1874). However, many indicators point to the metaphorical nature of San rock art. In a series of papers Lewis-Williams (1981, 1983) and others(Lewis-Williams & Loubser 1986; Lewis- Williams & Dowson 1989) identify many instances of trance performance and altered states of consciousness in paintings. They also demonstrate that many geometric designs such as spirals, chevrons and zigzags as well as more complex forms are analogous to the entoptic visions of modern shamans. From these observations they conclude tha tthe art is essentially shamanistic.

Lewis-Williams and Dowson (1989) also associate hand prints with potency and curing. In particular, they equate the potency of hand with the way San shamans cured by the laying on of hands and drawing sickness out of a patient and into their own bodies. They note that it "seems probable that making hand prints in a rock shelter was, at least in some ways, akin to painting eland. Both practices fixed potency on the walls. Some shelters are crowded with eland paintings, others with hand prints" (Lewis-Williams & Dowson 1989:108). Whilst this may represent one aspect of hand printing, however, it does not necessarily explain the predominance of sub-adult hand prints in the south-western Cape. Although the evidence is circumstantial it is tempting to relate the sub-adult hand prints to an initiation event along the lines of the Australian example mentioned above. The Bleek and Lloyd records contain many references to female initiation rites involving seclusion of young girls at puberty (Hewitt 1986; Solomon 1989). Alternatively, if the hand prints were the work of boys the situation would conform to the puberty ceremonies noted by Schapera (1930) among Kalahari hunter gatherer groups. The boys remain in a secluded place for several days and undergo certain privations and rites. After the ceremony "they are now regarded as men, they can marry, and they take part in the councils of men and associate with them" (Schapera 1930:125).

The possibility of this kind of initiation event being depicted in the art has been dealt with previously (Parking- ton & Manhire 1997; Parkington et al. 1996). The question here is whether seclusion sites involving hand prints exist and, if so, whether they can be identified? Before attempting to answer this question, we first need to clarify the differences between hand prints and other types of imagery. In the south-western Cape, we tend to make a distinction between fine-line paintings and images made with hands and fingers (Yatesetal. 1994). Briefly, fine-line images are those produced by using some kind brush or applicator which allows the creation of well defined lines, edges and colour transitions. The greater part of the representational imagery in the south-western Cape falls into this category. In contrast, there are also paintings produced with hands and fingers. These include hand prints, finger dots as well as some fairly crude finger paintings of humans and animals.

Many sites in the south-western Cape contain both hand prints and fine-line images but there are a number of sites where hand prints far outnumber all other kinds of images. There are also a few sites devoted entirely to hand prints but these are rare and most hand print dominated sites include a few other images such as marks, daubs and finger smears as well as occasional humans and animals. Maggs (1967) noted a similar trend in the Pakhuis area where sites with numerous paintings of human figures often included a few hand prints whilst sites with many prints had relatively few other paintings. The majority of hand prints appear to be later additions to sites which already contained fine-line painting. This suggests that although the location of the site as a focus for painting remained the same there was a change in the use of the site through time.

Two related and often debated questions are: when were hand prints painted and who were the artists? The first of these can be answered with some degree of confidence, at least for the south-western Cape, whilst the second depends to some extent on how one defines hunter-gatherers and herders. Although we have no direct chronology for hand prints, information on the relative dates of hand prints and fine-line imagery can be obtained from the superpositioning sequence. We have found no examples in the Sandveld or in the mountains of a finely detailed painting superimposed on a hand print, where as there are many clear examples of hand prints placed over finely detailed images (VanRijssen 1984; Yates et al. 1994). Although this does not tell us when hand prints were painted it clearly implies that they were executed at some period after fine-line images. To place the succession of fine-line imagery by hand prints within a dated frameworkwe need to examine evidence from the excavated and painted records regarding the introduction of domestic animals.

The introduction of a pastoralist economy in the south- western Cape is marked by the presence of pottery and sheep bones in archaeological deposits. Pottery first appears in the local coastal sequence between about 1800 and 1600 years ago. In the mountains, however, there is little evidence for pottery until about 1 000 years ago and there appears to be a lag of about 500 years between the common use of pots at the coast and in the interior mountains (Yates et al. 1994). It is more difficult to assess the first appearance of sheep remains as they are far less common but a date of around1 600 years ago seems to be indicated, after which they become more numerous at coastal sites (Klein & Cruz-Uribe 1987; Yates et al. 1994). Although sheep are also present at sites excavated in the mountains they are less common and never achieve the frequencies recorded at the coast.

The appearance of domestic animals in the painted record is also a clear indicator of the presence of pastoralist groups in the area. The domestic sheep, recorded historically as belonging to pre-colonial herding groups, are the fat-tailed variety with characteristic ears and tails, which facilitate secure identification of the species in the paintings. Although fat-tailed sheep have long been recognised as a component of south-western Cape art (Johnson et al. 1963; Rudner & Rudner 1970) they are not at all common. There are only 16 sites with sheep paintings out of a total of 1 591 rock art sites recorded in the south-western Cape. Their distribution is also of note as, with one exception, they all occur in the interior mountains. The sheep paintings are of particular value as they are one of the few images in the rock art record that can be linked directly to the archaeological record. As discussed above, sheep were present in the south-western Cape by about 1 600 years ago. This means that although the fat-tailed sheep paintings may be younger than this date, they cannot be much older.

The other interesting piece of evidence relating to domestic animals is the complete absence of any paintings of cattle in the south-westernCape. It is more difficult to ascertain the date of arrival of cattle in the south-western Cape as cattle bones are not common in the faunal record. In some sequences, however, sheep occur stratigraphically earlier than cattle perhaps indicating that they predated cattle by a few hundred years (Klein 1986). Notwithstanding the archaeological evidence, cattle clearly did achieve large numbers in the Cape at least by the sixteenth century, as is attested to by colonial documentation (Deacon 1984; Klein 1986).

The fine-line tradition, of which paintings of fat-tailed sheep are a part, appears to have terminated around 1 600 years ago at the coast and somewhat later in the interior mountains.It would seem that the fine-line tradition lasted just long enough for a small number of sheep to have been included but to have ended before the arrival of cattle. The evidence that fine-line paintings persisted longer in the mountains than at the coast is supported by the fact that all the fat-tailed sheep paintings, bar one, are at sites in the interior mountains. Hand prints, by virtue of the evidence of superpositioning, appear to succeed finely detailed painting and, by implication, paintings of fat-tailed sheep. If, therefore, finely detailed painting persisted until at least the introduction of pastoralism (c.1900- 1600 years ago) the practice of hand printing cannot have begun before this date.

The final piece of evidence for establishing the time depth of hand printing comes from paintings dating to the colonial period. These include depictions of colonially related subject matter which have long been recognised as a distinctive subset of south-western Cape art (Johnson et al. 1959; Johnson 1960). They occur at a number of sites in the Koue Bokkeveld and include examples of wagons, horses, guns and figures in European dress. They are characterised by a restricted range of subject matter and choice of colour appears to be limited to various shades of red. As such they are technically distinct from fine-line images and appear to have more in common with finger paintings, hand and even graffiti (Yates et al. 1994). In the Koue Bokkeveld, hand prints do in fact occur at sites with colonial imagery and at the cave known as Stompiesfontein some of the very large prints are rendered in the same shade of red as the historic drawings (Yates et al. 1993). This suggests that at least some of the hand prints are contemporary with colonial era subject matter. The paintings of colonial artefacts cannot be older than the seventeenth century AD, when the first settlers arrived from Europe, although they maybe younger. Evidence from the archival records of the period indicates that a late eighteenth century date is most likely (Yates et al. 1994). The colonial era paintings thus not only support the argument for a precolonial end to finely detailed paintings but also suggest that hand printing persisted, at least in the Koue Bokkeveld, until the arrival of European colonists.

Several authors (Ruder & Rudner 1959; Willcox 1959, 1960, 1984; Van Rijssen 1984, 1994 for example) have commented on the possibility of pastoral Khoikhoi groups being involved in the production of rock paintings in the south-western Cape. The fact that hand prints succeed finely detailed images does not imply that the artists were necessarily the historically documented pastoral Khoikhoi. As noted earlier (Yates et al. 1994), there is simply insufficient evidence concerning the history of pastoralism in the south-western Cape to arrive at any specific conclusion as to the identity of the hand print makers. Be that as it may, the much improved details of the distribution of hand print sites (Fig. 3) do shed some new light on the problem. Plain hand prints in particular are not restricted to any specific localities and their distribution virtually matches that of fine-line images. Judging from the evidence of early European travellers (Thom 1952, 1954; Raven-Hart 1967), Khoi herders favoured areas with suitable pasturage and water for their livestock. It would thus seem unlikely that the herders were responsible for hand prints in the interior mountains particularly as they mostly occur at the same sites as fine-line images. A better case for Khoi authorship could be made for the decorated hand prints as they are restricted to the coastal plain and the mountains fringes (Fig. 4) which are areas more suitable for domestic animals. Unfortunately, very few of the decorated prints are complete enough to allow accurate measurement so it is not possible to comment on their size.

The making of hand prints coincident with the demise of finely detailed imagery suggests not only a change in the technique of production of art but also a change in the role of image making. The involvement of mainly sub-adults in the production of hand prints, often in large shelters with few other paintings, implies a special event or occasion focusing on a particular age group. Although we have, as yet, an incomplete understanding of the process by which pastoralism was introduced into the south-western Cape, the production of hand prints appears to be one of several changes occurring at more or less the same time between about 1 900 and 1 600 years ago.

In summary, two points need to be emphasised. Firstly, hand prints are patently very different from fine-line paintings. They represent a conceptual and technical departure from the carefully drawn images of humans and animals which characterise much of the earlier art. In contrast to fine-line images, the production of hand prints is a simple process involving the replication of the same image again and again. Many sites contain large numbers of hand prints and although sites with very small numbers of prints do exist they are the exception rather than the rule. Measurements of prints show that several individuals were involved in hand print production at the majority of sites. This strongly suggests that hand printing was a group-activity rather than a solitary endeavour.

The second point is the crucial observation that hand prints are primarily the work of sub-adults. The fact that a number of young people were involved in a group activity, in a rock shelter suggests that some kind of special event or ceremony was being acted out. Obviously we have no way of knowing the precise details but the participation of a group of sub-adults points towards an initiation event involving rites of passage. Presumably the making of hand prints was only one aspect of the ceremony but it is the only part which remains today as a visible trace of what may have happened.

The superpositioning sequence indicates quite clearly that the numerous paintings of animals and humans found throughout the south-western Cape predate hand printing. These images are part of the widespread tradition of finely crafted paintings, which predate the influence of pastoralism. The succeeding episode of hand printing left large numbers of prints on the walls of rock shelters and caves alongside and sometimes overlaying the remnant animal and human images. The emphasis on involvement of sub-adults, the methodical repetition of the same motif and the probability that many prints were done at the same time signifies a change of attitude towards wall painting. Although we can still only hint at the actual function of hand printing it would seem that hand prints and other paintings which eventually replaced finely drawn images in the south-western Cape should not be viewed as a degeneration of artistic standards but rather as a change in the role of painters and painting.

Many of the authors quoted in this paper use different spellings for Khoisan groups.To avoid any confusion, the spelling of all the Khoisan groups mentioned in the text follows the standard method of Barnard (1992).

I am grateful to many people who assisted with this research project, in particular Royden Yates, John Lanham and students from the University of Cape Town. I am especially grateful to Maciej Henneberg who made the project possible and John Parkington for invaluable comments on the manuscript. I would also like to thank the referees for their comments and the Centre for Science Development and the University of Cape Town for supporting this research.

Barnard, A. 1992. Hunters and herders of southern Africa. A comparative ethnography of the Khoisan peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bleek, D.F. 1927. Buschminner von Angola. Archaeological Anthropology(ns) 21:47-56.

Clark, J.D. 1959. The prehistoryof southernAfrica. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Dart, R.A. 1937. The physical charactersof the /'Auni-≠Khomani Bushmen. Bantu Studies 11 (3):175-246; Appendix: A-W.

Deacon, J. 1984. The Later Stone Age of southernmost Africa. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

Ellis, F.H. & Hammack, L. 1968. The inner sanctum of Feather Cave,a Mogollon sun and earth shrine linking Mexico andthe southwest. American Antiquity 33: 25-44.

Henneberg, M. & Mathers, K. 1994. Reconstruction of body height, age and sex from hand prints. South African Journal of Science 90: 493-496.

Hewitt, R.L. 1986. Structure,meaningandritualin the nar- ratives of the southern San. Quellen zur Khoisan-For-schung. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

Johnson, R.T. 1960. Rock paintings of ships. South African Archaeologic a lBulletin 15:111-113.

Johnson, R.T. Rabinowitz, H. & Sieff, P. 1959. Rock paintings at Katbakkies, Koue Bokkeveld, Cape. South African Archaeological Bulletin 14:99-103.

Johnson, R.T. Rabinowitz, H. & Sieff, P. 1963. Who were the artists? South Africa nArchaeological Bulletin 18:27 & cover.

Klein, R.G.1986. The prehistory of stoneage herders in the Cape Province of South Africa. South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 5:5-12.

Klein, R.G. & Cruz-Uribe,K. 1987. Large mammal and tortoise bones from Eland's Bay Cave and nearbysites, western Cape Province, South Africa. In: Parkington, J.E. and Hall, M. (eds) Papers in the Prehistory of the Western Cape, South Africa:132-163. Oxford:British Archaeological Reports.

Lebzelter, V. 1931. Zur Anthropologie der Kung Buschleute. Anz. Akad. Wiss. Wien.M-N. K1.68:24-26.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1981. Believing and Seeing: symbolic meanings in southern San rock painting. London: Academnic Press.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1983. Introductoryessay: science and rock art. South African Archaeological Society Good- win Series4:3-13.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. & Dowson, T.A. 1989. Images of power:understandingBushmanrockart.Johannesburg: SouthernBook Publishers.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. & Loubser, J.H.N. 1986. Deceptive appearances: a critique of southern African rock art studies. In: Wendorf, F. & Close, A.E. (eds) Advances in World Archaeology 5:253-289. New York: Academic Press.

Lloyd, L. 1911. Specimens of Bushman folklore. London: Allen.

Lundy, J.K. & Feldesman, M.R. 1989. The femur/stature ratio: a method to estimate living height from the femur. Unpublished paper presented at the 41st Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, Las Vegas, Nevada, 13-18 February 1989.

Maggs, T.M.O'C. 1967. A quantative analysis of the rock art from a sample are a in the western Cape. South African Journal of Science 63(3):100-104.

Manhire, A.H., Parkington, J.E. & van Rijssen, W.J.J. 1983. A distributional approach to the interpretation of rock art in the south-western Cape. South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series4:29-33.

Orpen, J.M. 1874. A glimpse into the mythology of the Maluti Bushmen. Cape Monthly Magazine9(49):1-13.

Parkington, J.E. & Manhire,A.H. 1997. Processions and groups: human figures, ritual occasions and social categories in the rock paintings of the western Cape, South Africa. In: Conkey, M., Soffer, O., Stratmann, D. & Jablonski,N.G. (eds) Beyond art: Pleistocene image and symbol. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences Number23:301-320.

Parkington, J.E.,Manhire,A.H. & Yates,R.J.1996.Read- ing San images. In: Deacon, J. & Dowson, T.A. (eds) Voices from the past./Xam Bushmen and the Bleek and Lloyd collection:212-233. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand UniversityPress.

Raven-Hart, R. 1967. Before Van Riebeeck. Cape Town: Struik.

Rudner, I. & Rudner,J. 1959. Who were the artists? South African Archaeological Bulletin 14:106-108.

Rudner, J.& Rudner,I.1970. Thehunterandhisart.Cape Town:Struik.

Schaafsma, P. 1980. Indian rock art of the southwest. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Schapera, I. 1930. The Khoisan peoples of South Africa: Bushmanand Hottentots. London:George Routledge & sons.

Schultze, L. 1928. Zur Kenntnis des Korpers der Hottentotten und Buschmanner.Jena: Gustav Fischer Verlag (JenaischeDenkschrift18).

Seiner, F. 1912. Beobachtungenund Messungenan Buschleuten. Zeits. f. Ethnol.44:275-288.

Seiner, F. 1913. Beobachtungenan den Bastard-Buschleuten der Nord-Kalahari. Mitt. Anthrop. Ges. Wien. 43:311-324.

Shennan, S. 1988. Quantifying archaeology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Sieveking, A. 1979. Thecaveartists.London:Thames & Hudson.

Solomon, A.C. 1989. Division of the earthgender, symbolism and the archaeologof the southern San. Cape Town: University of CapeTown, MA thesis.

Thom, H.B. (ed.) 1952. Journal of Janvan Riebeeck. Volume 1. Cape Town: Balkema for the Van Riebeeck Society.

Thom, H.B.(ed.) 1954. Journal of Janvan Riebeeck. Volume 2. Cape Town: Balkema for the Van Riebeeck Society.

Tobias, P.V. 1962. On the increasing stature of Bushmen. Anthropos57:801-810.

Tobias, P.V. 1972. Growthand stature in southern African populations. In: Vorster, D.J.M. (ed.) The human biology of environmental change :96-104. London: International Biological Programme.

Trezise, P.J. 1969. Quinkancountry.Sydney: A.H. & A.W. Reed.

Truswell, A.S. & Hansen, J.D.L. 1976. Medical research amongthe !Kung.In Lee, R.B. & DeVore, I. (eds) Kalahari hunter-gatherers.Studies of the !Kung San and their neighbours:166-194. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Van Rijssen, W.J.J. 1984. South-western Cape rock art who painted what? South African Archaeological Bulletin 39:125-129.

VanRijssen, W.J.J.1994. Rock art. The question of authorship. In Dowson, T.A. & Lewis-Williams, J.D. (eds) Contested images: diversity in southern African rock art research: 159-175. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Walsh, G.L. 1988. Australia's greatest rock art.Bathhurst: E.J.Brill/Robert Brown and Associates.

Wells, L.H. 1952. Physical measurements of northern Bushmen. Man 52:53-56.

White, H. 1995. In the tradition of the forefathers. Bushman traditionality at Kagga Kamma. Rondebosch: University of Cape Town Press.

Willcox, A.R. 1959. Hand imprints in rock paintings. South African Journalof Science 55:292-298.

Willcox, A.R. 1960. Who were the artists? Another opinion. South African Archaeological Bulletin 15:23-25.

Willcox, A.R. 1984. The rock art of Africa. Johannesburg: Macmillan.

Wilson, M.L. 1990. Strandlopers and shell middens. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, MA thesis.

Wilson, M.L. & Lundy,J.K.1994. Estimated living statures of dated Khoisan skeletons from the south-western coastal region of South Africa. South African Archaeological Bulletin 49:2-8.

Yates, R.J.,Manhire,A.H. & Parkington, J.E.1993. Colonial era paintings in the rock art of the south-western Cape: some preliminary observations. South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 7:59-70.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ Hand Paintings in Rock Art

→ Hand Paintings in World Rock Art

→ Cueva de las Manos | Cave of the Hands

→ The Role of Hand Prints in the Rock Art of the South-Western Cape

→ Handprints in the Rock Art & Tribal Art of Central India

→ Hand Stencils in Chhattisgarh India

→ Hand prints found in Altamira

→ Handpas Project

→ Prehistoric Hand Paintings in the Cave of Maltravieso

→ Hand stencils and their missing fingers

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network