The Dynamic process of erosion created overhung walls which attracted the Painters and sustained their art. Here we see the aftermath of erosion in a soft layer of bedded volcanic ash at the base of the formation. When sufficiently undermined, the harder layer above suffered stress fractures from its own weight, and great sheets of stone dropped into the void left by the erosion. The Painters created their art on the fresh surface thus exposed.

At Cueva de la Serpiente, can be found the most extraordinary composition in the Great Mural area. This 26-foot-long panel, apparently painted by one artist. No other site displays fanciful creatures like these deer-headed serpents, nor do others show large groups of interrelated figures like those clustering around the sinuous body of the snake-monster on the right. As if to heighten the mystery of this unique conception, the smaller figures do closely resemble the work of Painters at other sites. The photograph of the area between the serpents shows the rough surface on which this great work was rendered - and attests to the fidelity of Joanne Crosby's recreation of the entire panel.

The composition of the work, when seen close at hand, is striking as a whole and full of fascinating details. A serpentine figure forms the literal spine of an assemblage fleshed out with over 50 doll-like human and animal figures. The sinuous form of the serpent and these lesser bodies were conceived and executed as a unit. The small figures do not interfere with the movement of the large one; indeed, their placement creates an odd, rocking effect that enhances the apparent weaving of the serpent.

This pair of deer from El Parral, provides an illustration of a paradox in the realism of the Painters' style: Outlines of these and most other figures were drawn as recognizable animal forms but then in-filled with arbitrary and fanciful patterns.

La Natividad rock shelter is five hundred feet long and one hundred feet high, and probably the largest painted rock shelter in Baja California. Late in the Painters' era, the continuing process of cave formation caused a great section of the back wall to collapse in giant fragments that still choke the west end of the sheltered area. The Painters decorated the freshly exposed surface with scattered figures of deer painted in a homogeneous style. Other parts of the cave retain older works, now faded or fragmented, that were closely spaced and more varied in style and subject matter.

From the cave of El Batequi, this detail from the right end of the painted ceiling illustrates several of the Painters' conventions and techniques in four or five distinguishable layers of overpainting. White outlining is conspicuous, as are two examples of twisted perspective. Breasts on the woman at the upper left appear to issue from her armpits because they are depicted in double profile. The same distorted perspective causes dewclaws on the deer to appear unnaturally splayed, producing curious handlike hoofs.

Paleolithic cultures on every inhabited continent produced pit-and-groove rock engravings, but even very similar works may have been done for different reasons. A creative act which was part of a puberty rite in one group may have been a shaman's means of divination in another. So, perhaps, with rock art. No matter how similar, works of different times and places may have had different inspirations. The media available to artists are far more limited than the range of ideas they attempt to express.

The art of El Batequi stands in the most marked contrast to that of El Parral. El Batequi has far fewer sites. No more than five or six truly separate locations can be counted, but four of these are major painting centers, each with over 100 figures. El Batequi is distinguished by many masterfully executed figures. More important, it shows an unprecedented degree of cooperation among its major artists. Painters unknown numbers of years or generations apart, not only respected but added to what they found; the product is a powerful composition. This attribute spotlights the place among the Painters' work because the norm is diametrically opposite - most assemblages of figures from different hands and times have resulted in disarray and chaos. In a land where overpainting was the rule, successive artists usually obliterated the works of their predecessors. The priceless mural at El Batequi shines down from its ceiling as a glorious exception.

3,500 feet above sea level lies La Cuevona. The cave is vast and beautiful. Under the brow of the cliff, the elements have eroded an ovoid space about 200 feet long, 60 feet high & 80 feet deep. The huge windswept void houses Great Mural art. This immense eye-socket cave in a steep wall of Cañada del Cerro is one of the least accessible of the Painters' sites. Although the few paintings of giant men & deer on its walls are not outstanding examples, this cathedral-like space, and the experience of reaching it, create beautiful memories of the land.The wonder was that people had labored up to such a place to paint at all, not that they had failed to return in repeated cycles. Unfortunately, the painted figures of La Cuevona are in a very diminished state. The same erosive forces that created the cave persist, and its rock art has not been spared. The relatively soft agglomerate rock the Painters chose as their canvas continues to loosen bit by bit, and falls to be scoured away by winds that whip those towering heights. While one mono at the center of the cave's back wall is only a shadow, two others still assert a degree of their half-red and half-black presence. Off to the right, the procession of deer is gradually weathering away.

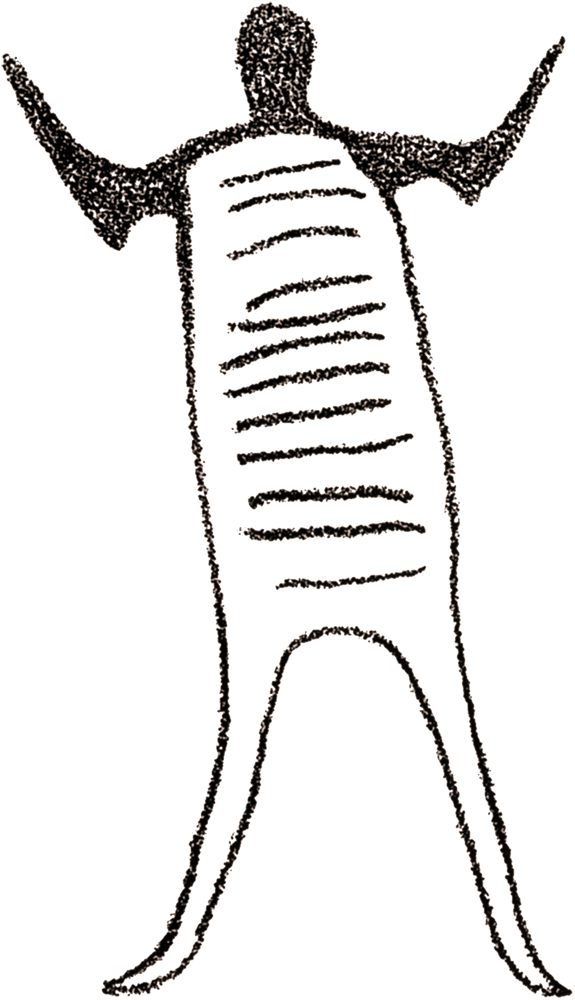

On a wall a little less than 100 feet long were painted several dozen figures, large and small, dominated by two fine large deer and three monos - two large and one small - which gave the impression of being a man, a woman, and a child. The large male mono is unique in being drawn with a heavy red outline filled in by horizontal bars that led us to dub him "ladder-man."

Cueva Obscura ("The Dark Cave") is about 80 feet deep, 50 feet wide, and 30 feet high at its apex, the largest true cave with significant Great Murals known to Harry Crosby. Three walls of the deep, small-mouthed cave display handsome, sophisticated groupings of animal and human figures.

The Cueva del Ratón is located at the highest elevation of any painted cave of importance in the Sierra de San Francisco. It is on the eastern edge of a ridge dropping down from the high ground of Cerro de la Laguna, and it is more of an overhang or rock shelter than a true cave. The painted area is about 40 feet long and exhibits a small but choice collection of the Painters' art: colorful figures of deer, borregos, rabbits, humans, and a mountain lion.

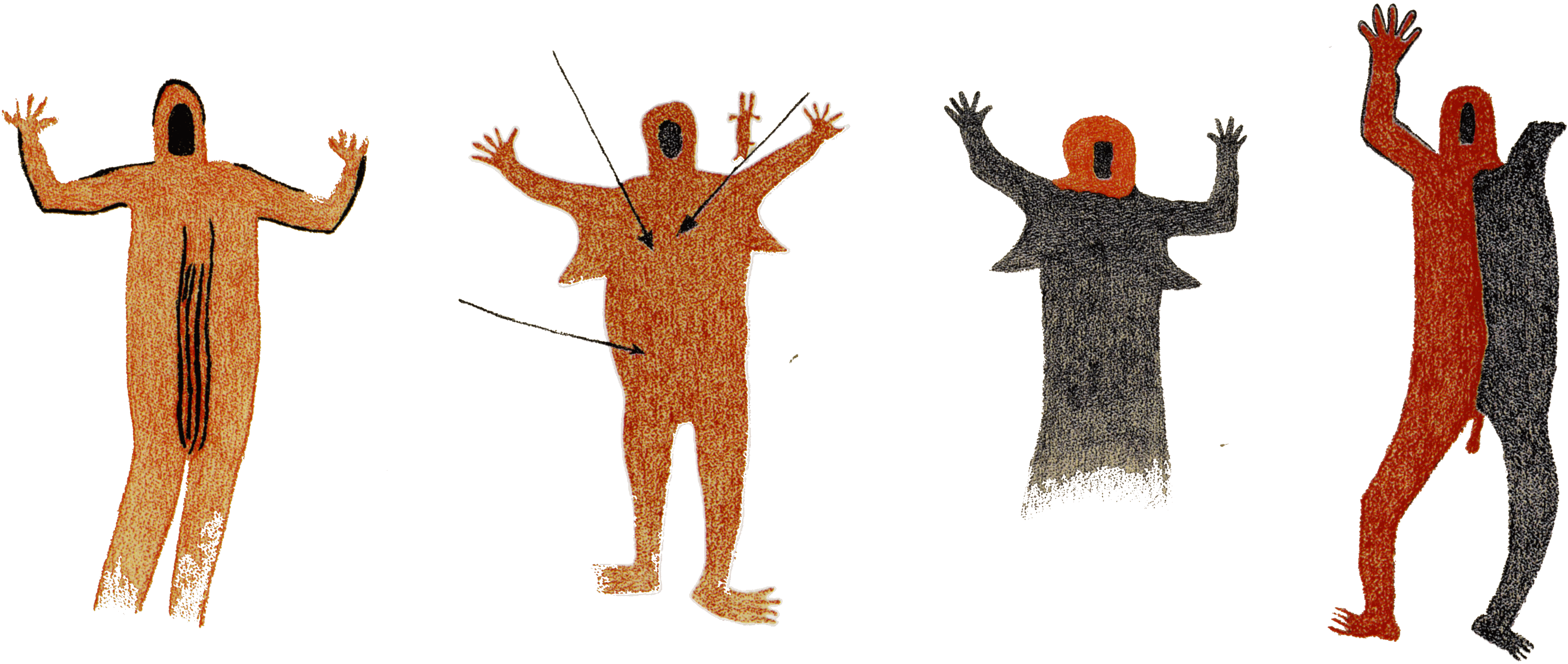

One large mono represents a rare type. The figure was divided into red and black areas along the vertical axis in the usual fashion, but a black oval was heavily painted over the area where we would imagine a face. In addition, both the red and black portions of the body were colored in fine vertical stripes rather than solid paint. This curious face patch has turned up at only four other sites: Cuesta del Palmarito (below left) about four miles to the southeast, and El Carrizo (below middle left), Los Monos de San Juan (below middle right), and El Cajón del Valle (below right), 50 miles to the south and in a different sierra, that of Guadalupe. As a further curiosity, the coloring in vertical lines is much more common in the sierras of Guadalupe than it is in the Sierra de San Francisco.

A black lion also commands attention. Such painted representations of mountain lions occupy a special niche in the Painters' repertory. For some reason, mountain lion figures vary less than any other, animal or mono. They all have long, stiff, extended tails and short legs cocked at similar angles. There is virtually no neck, and a round, short-muzzled head is set with small round ears. Most leones are black but several red examples have turned up, and even one in ochre. Oddly, the painted images of these animals are never bicolored. They are unique in this respect.

Certain artists appear to have worked in several of the great painted centers. The mountain lion and the rare black-faced human from Cueva del Ratón were virtually duplicated at Cuesta del Palmarito and elsewhere. Similar resemblances seem to link the histories of many painted caves. However, other artworks may be unique to their sites. For example, no counterparts are known for the elegant murals at El Batequi or the Serpent Cave. Certainly, some aspect of the Painters' religion dictated that art be located in specific places - a dictum that took precedence over convenience and maintaining the integrity of earlier works. Shamans apparently were stern taskmasters: Some art can be found at amazingly inaccessible sites, and other works, like this one at Santa Teresa, seem unnecessarily high on a wall that is otherwise unpainted.

The central effigy of this painting from Cueva de las Flechas is impaled and overlaid with arrows, one of many puzzles in the Painters' symbolic vocabulary. Images of animals transfixed by arrows are common in the Sierra de San Francisco, but human figures so treated are rare. However, in the sierras of Guadalupe and San Borja, both are common. Some sites in all regions fairly bristle with figures wounded by spears and arrows, yet El Batequi, with its many figures, exhibits no weapons at all. What was the message? These powerful figures act out an elaborate charade for which we have not yet guessed the first word.

Cueva Pintada is the location of Baja California's foremost center of primitive rock art. The largest collection of Great Murals, and those in the best condition, are found in this shallow recess eroded from the nearly vertical east wall in the central part of Arroyo de San Pablo. Note the situation of the cave and the proximity of native palms that could have been used to make ladders or scaffolding to reach high up on the backwall of the shelter. Although the cave appears small here, it measures 500 feet across the base of the opening.

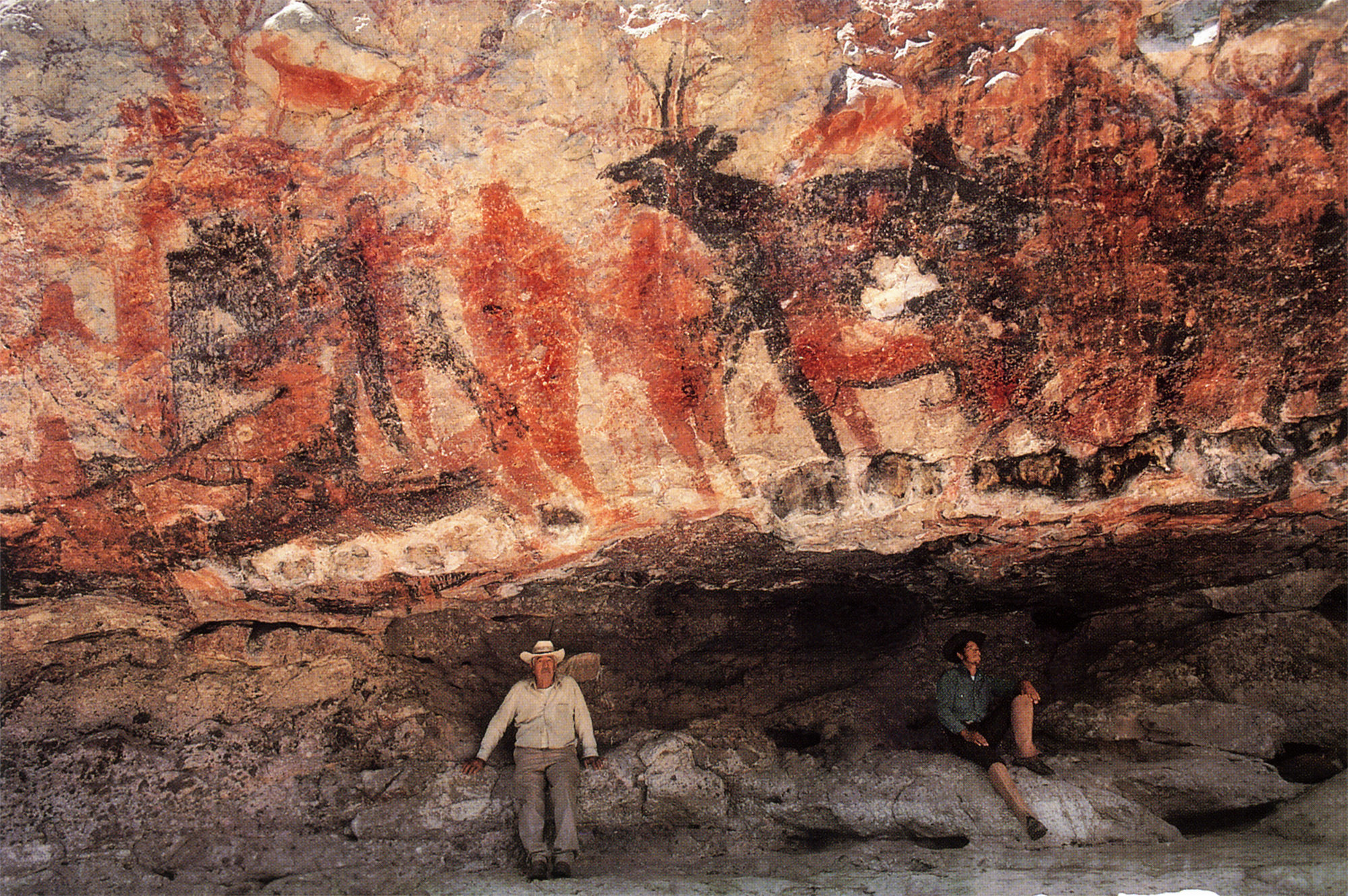

The great south panel, pictured above with the Harry W. Crosby and Tacho Arce to provide scale, is remarkable for its fine condition and the homogeneity of its painted figures. This grand cave is the most painted place in the most painted part of the entire range of the Great Murals. It may rightly be considered the focus of the phenomenon. The cave itself, while close to 500 feet in length, is at no point very deep, perhaps 40 feet at most, and for half its length it is low ceilinged and shallow as well.

The quantity of well-preserved painting at Cueva Pintada is a function of two factors that extend beyond the will of the Painters: the size of the cave and the durability of its rock surfaces. In the latter respect, this place is remarkable. Many other sites were as heavily painted per square foot of wall space, but in very few is the ratio of survival so high. This is due in part to a relatively recent event in the history of the cave's formation. At the south end of the shelter, a section of the back wall some 100 feet long is covered with over 40 grand images, principally monos , deer, and borregos. Although these were overpainted to a depth of at least three layers, the group is in the best condition of any with a comparable number of large figures to be found in the entire range of Great Murals. A line of large rock fragments lies just below this heavily painted respaldo. Inspection shows that they fell relatively recently from the wall above, leaving it a clean, little-eroded surface. It appears that the excellent condition of these paintings is due in large measure to the fresh character of the rock on which they were painted. Most other respaldos apparently were already weathered and beginning to disintegrate before any paint was applied. Afterward, the process continued and the paintings suffered.

Cueva Pintada is so wide and irregular that it provided the Painters with two very different sorts of rock shelter. The above photograph shows a recessed wall painted to a height of 30 feet. In the central part of the cave, the back wall is too soft to sustain paintings, but a ceiling of excellent rock supports an amazing gallery. This view looks south toward Cueva de las Flechas on the opposite wall of the arroyo.

Was each wall an altar, each painting an offering? We do not understand the reasoning that led to the placement of the Painters' art. Most of the time, they superimposed new images on old, showing little concern for the visibility of existing works or of those being added. They obviously valued the act of painting in particular places more than they valued the show that resulted.

The approximately 300 different painted caves and shelters thus far discovered in the Great Mural area vary widely in size, exposure, rock condition, and other factors that affect the survival of painted art. Many combinations are possible. Large, well overhung shelters often were formed from soft rock and lost their paintings quickly. Here, a small, little-protected site at El Brinco includes a durable rock surface that preserves an attractive group of paintings.

A striking display of Great Mural art (above right) is hidden in a vast open cave high above a minor watercourse in a central but particularly inaccessible part of the sierra . Durable rock and good protection explain the well-preserved paintings of men, women, deer, rabbits, and fish. The remoteness of such places from scenes of hunting or food gathering and the relative absence of artifacts suggest that people visited them only to produce the huge paintings and then to commune with them.

A minor cave with major art, Boca de San Julio is about 70 feet long and 8 to 12 feet high, unfortunately the stone of Boca de San Julio is quite soft - it sheds its substance in a constant sloughing of grains, and all the paintings have been damaged in the process. At the west end is the greatest concentration of works, several large and small deer much overpainted. Under them are a large number of smaller figures including rabbits, birds, monos (actually half-monos as at Cueva de las Flechas), and an odd half-red, half-black image in a damaged state, that appears to be a depiction of a chubby seal or sea lion.

Cuesta de San Pablo, the walls of this cave eroded from a gray conglomerate made up of fine particles. The form of the eroded surface is unusual in that it mimics the character of draped material. This curtained pattern parts to leave two fairly smooth clear areas about twelve feet high. That on the left was decorated with a rather stylish if unintentional grouping of three distinguishable figures: a deer; a gato montés, or bobcat; and a mono. The bobcat closely resembles the Painters' depiction of a mountain lion except that it bears a well-defined, stubby tail.

A few subjects made up the majority of the Painters' artistic images; humans and deer abound. However, if one is patient and looks into every corner, he will find diversity. Here, in a small cave at Cuesta de San Pablo, seldom-portrayed manta rays provide the principal show. The Painters visited their two shores and knew many forms of sea life in detail - as they proved with skillfully created images of fish, turtles, sea mammals, and shorebirds placed on cave walls 25 miles from the nearest arm of the sea.

San Gregorio, lies at about the geographic center of the area's rock art locations. San Gregorio I, consists of a low cave about 100 feet long located at the base of a formidable respaldo. The ceiling of the shallow cave is heavily painted with large and small figures of nearly every sort found in the Great Mural area. Most of these are in reasonably good condition and this assemblage alone would constitute a major example of the Painters' range and skills. However, on the respaldo outside and above this ceiling exhibit there is a procession of men and beasts surpassed only by El Batequi in artistry and composition - and by no other in power and thrust. As at El Batequi, the effect was fostered by a tacit cooperation among the artists who painted different areas or repainted those already used. It is noteworthy that the flow of running, pressing animals here is from right to left, the reverse of El Batequi. In further comparison, San Gregorio has a harder, rougher rock and its colors are the more vivid as a result. The drawings at El Batequi seem finer and surer. In balance, both these grand canvases are profoundly impressive: San Gregorio the more immediately striking, El Batequi the more sophisticated expression.

This 60-foot-wide "mural" at San Gregorio is, in fact, a progression of many dozens of interlaced human and animal forms painted at different times and partially overlapped. As this parade developed, each artist may have been concerned only with adding his new figure, but a modern viewer finds it easy to synthesize the separate images into a meaningful work of art.

Whereas the grand exterior panel displays a parade of large figures, the roof of the inner space is painted and overpainted with a complex assortment of smaller images - small mammals, birds, snakes, and fish - rich in colors and forms, but difficult to isolate and appreciate.

A stranded whale or great ray would have attracted much attention since it could supply a whole band with an unprecedented cache of protein. This painting seems to show a whale broaching, an event the artist could have seen at Scammon's Lagoon; but the strange rear appendages lead some viewers to identify this figure as a pinniped - either a sea lion or an elephant seal.

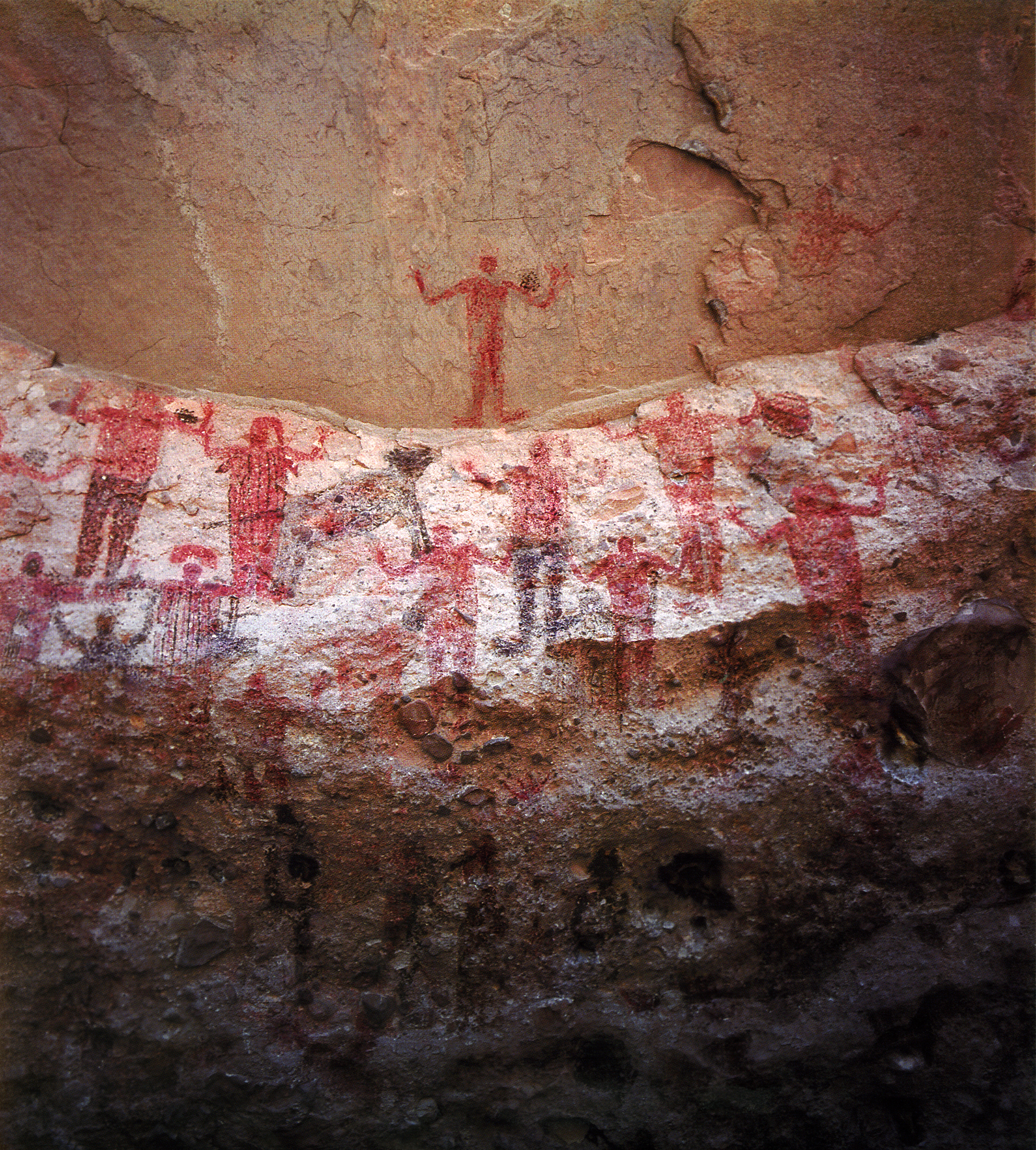

A little over a mile below Rancho San Gregorio is an inconspicuous cañada called La Palma one of the richer rock art galleries left by the Painters. The site consists of a 200-foot respaldo located 50 or 60 feet above the caja on the east side. Near the north end of this wall, the lower part is undercut to form a deeper shelter. At the north end of the greater respaldo, a small cave has formed which penetrates the base of the respaldo to a depth of 20 feet. Each of these areas is painted in its own significant and distinctive fashion. At the right end of the large outer face of the respaldo, an array of monos exhibits a degree of order unmatched at any other site. Two rows of larger-than-life figures are ranged one above the other. These monos are spaced at about arm's length. The style, paint, and proportions are similar in all figures and the rows are the result of plan, not accident. These monos are typical of those created late in the epoch of the painting phenomenon: All are lightly colored, the paint applied sparingly and in streaks that suggest chalk or dry-brush strokes. In a very rare combination, the single female figure in this group, clearly identified by breasts jutting from the armpits, is wearing a headdress of three small feather like projections, one of few instances in which a female mono was outfitted with any sort of headgear. Several male figures have headdresses of the sackhat variety, and in one case the lower half of the body and legs are painted black, a decorative scheme that gives the figure the appearance of wearing trousers. The body and legs of another sackhat figure are in-filled with a regular pattern of alternating red and black stripes. Two counterparts of this curiosity are found side by side at Cuesta del Palmarito and another has been described at El Corralito. These four figures are so similar that they constitute one of the few cases where we can be quite sure we are seeing the work of a single painter at more than one site.

Farther to the left, the outer wall is profusely decorated with other less regularly placed monos and several large borregos. These representations of bighorn sheep are as fine as those at any other place, and they occur here in impressive combinations. All were painted with heads raised to best exhibit noble representations of their distinctive horns. Another noteworthy feature of the middle wall area is the presence of four rather crudely drawn fish. One of these almost certainly represents a shark and is delineated as a profile, a rare occurrence.

The lower, better-sheltered part of the respaldo is decorated with a remarkably integrated group of monos knows as The Family. Unlike the rows of their regularly spaced fellows already described, this group of eight is arranged shoulder to shoulder in a partially superimposed fashion which suggests an actual event. Other factors contribute to the perception by modern viewers that these were real people: The group is painted near the level of the shelter's floor so that one confronts the figures more at eye level than is customary. The figures are unusually naturalistic; their heads are rounded and set on perceptible necks. The decorative pattern used on two of the figures suggests clothing, and finally, a small black mono is placed in such a way that it creates the illusion of being a child. The total effect of this assemblage is very compelling; it is perhaps the most human of all the Painters' efforts.

Just above and to the left of this most appealing work is one of the rare representations of a Pronghorn Antelope, the berrendo, now almost extinct on the peninsula. Fortunately, this skillful and lively representation is in excellent condition.

Blazoned on the domed ceiling of a cave within a shelter, this rich mural (La Palma Borrego), even in its present damaged state, radiates genius in both color and design. Three huge black forms crowd the vault; these fine examples of the Painters' bighorn sheep are magnified by their surroundings. The art fairly bursts the bounds of the space.

At its mouth, the cave of La Candelaria is about 100 feet wide and 40 feet high and its interior is complex in form. The opening faces west and the northern part of the cave is quite shallow with a nearly vertical back wall. The southern portion is much deeper, running back 50 feet or so from the entry. Between these dissimilar areas is a structure unique to La Candelaria: A sort of natural staircase leads from the central part of the cave up to a point quite close to the ceiling and near the center of the back wall.

This ready-made scaffolding was not wasted by the Painters. Exactly at its top, we found the supremely beautiful deer of La Candelaria, its antler-crowned head thrown back as if in the agony of the chase. This image, in spite of its damaged condition, asserts itself in any company as an expressive work of art.

There was a bond between artist and animal. Whatever their motives for decorating caves, the Painters displayed an affinity for the creatures they pictured. Deer are shown impaled by arrows or spears; with legs broken by throwing sticks; or gasping, open-mouthed, perhaps run down in a chase. Nevertheless, the grace and symmetry of the animals shine through. These animals were not merely pieces of meat on the hoof; they were given spirits.

Elsewhere, as well, the cave proved to be a treasure house. Much, much art has been irrevocably lost to erosion, but the surviving works include a high percentage of rare and beautiful images. The last major figure at the north end depicts a berrendo (above right) in the Painters' best bicolored tradition. This and the all-red berrendo at La Palma are among the few representations of this animal found in peninsular art, and this is the finest of the lot. The drawing and execution are exemplary and the image apparently includes a rare example of the Painters' techniques for suggesting animation; in this case the animal was given two pairs of forelegs, one thrust down and the other forward. Laid over the antelope's body is the painting of a slim arrow with a well-defined point. Abstract, semi-geometric figures occupy wall spaces adjacent to the antelope image. Above the antelope is a shield-shaped white outline filled in with a carefully painted checkerboard in alternating hues of black and ochre-yellow. Below the antelope is another prominent checkerboard done all in ochre. Only three painted images that can confidently be identified as antelope. This example shows the long neck and short body common to all three. The site of El Enjambre de Hipólito consists of a respaldo painted for about 60 feet of its length. At the right end of the painted area is a deeper alcove about 10 feet tall and 20 feet broad. This recess was heavily painted with large handsome figures primarily in red and outlined strikingly in white. The massing of the figures and the form of the shelter suggest a primitive shrine, and a close inspection showed, within this niche, a high percentage of figures notable for artistic merit and good preservation. Although there are fine deer, borregos, monos, and striking depictions of birds, this site is dominated by the unusual prominence of large stout-bodied fish (below left). It is a rare experience to see fish portrayed almost as large as human figures and given equal footing in the presentation.

The Cuesta del Palmarito site was known for centuries to missionaries and travelers. During both prehistoric and mission periods, major trails passed within easy view of this cave's great arched entrance - which probably made it the most visited of all Great Mural locations. In its highest row of paintings, a collection of human figures displays unusually varied headdresses and decorations. Some appear clothed, a possibility so welcome to the decorous Jesuits that it contributed to their belief that the region had once been populated by a more civilized people.

This account of art discoveries has been structured around the separate drainage systems in the Sierra de San Francisco. That plan fits the terrain and the distribution of paintings very well, up to a point. The arroyos certainly are logical as geographic subdivisions, and several of them clearly served as avenues for prehistoric humans. However, this clockwise circuit of the sierra's arroyos has not revealed the whole story or even all that is observable at present. At least four arroyos on the west side of the sierra were not entered in the course of my study, and the same neglect applies to the large piece of ground on the northeast corner of the sierra, a region whose potential was discussed earlier.

Apart from areas not investigated, the pattern of this presentation also neglects several interarroyo relationships that may someday help us to understand the Painters' activities in the sierra and their relationship to the occupation of nearby lower ground and the coasts. On the basis of their heavily painted state, it was surmised earlier that El Parral and San Gregorio were major routes in and out of the San Francisco highlands. El Batequi and Cuesta Blanca seem to have been lesser arteries. All of this could be deduced to some degree from evidence found within the individual arroyos. But a great deal of art (and, hence, proof of human activity) has been found along Cañada de la Soledad and in Arroyo de San Pablo within a mile of the cañada's mouth. The region thus defined is in the heart of the sierra and, up until now, was assumed to have been very isolated. In fact, this may not have been the case.

A look at the map of the whole sierra shows that Arroyo de San Gregorio, heavily painted, drains the northeast portion of the high ground. Its upper reaches, the arms called San Gregorito and San Julio, both touch the very divide of the mountains, and they do so within 100 yards of the corresponding fingers of La Soledad that drain the western side. Thus, the most heavily painted avenue on the east communicated directly with the drainage in which we find the great complex of painted places including El Brinco I, La Soledad, Cueva de las Flechas, and Cueva Pintada. This connection seems more than a coincidence. Even without the painted record, the route could be identified as the most direct trail with permanent water to cross the central high ground. Further exploration west of Arroyo de San Pablo may indicate an equivalent route or routes in the direction of the Pacific.

The ancient paintings in the Sierra de San Francisco are just beginning to be studied for their obvious value as elements in reconstructions of regional prehistory. However, unlike many humbler artifacts, the more inspired of these paintings embody a timeless genius that speaks to us in any context - art for art's sake.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ America Rock Art Index

→ The Rock Art of Baja California

→ Baja On Film

→ California Rock Art Foundation

→ Baja In Search of Painted Caves

→ Baja Great Murals Gallery

→ Sierra de San Francisco

→ Baja 2018 Expedition

→ The Rock Art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands

→ Color Engenders Life

→ The Rock Art of Arizona

→ The Rock Art of Nevada

→ Coso Sheep Cult of East California

→ Coso Range Rock Art Gallery

→ The Rock Art of Moab Utah

→ The Rock Art of the Oregon Territory

→ RAN - USA Colloquium 2018

→ Removal & Camouflage of Graffiti

→ Graffiti Dates & Names

→ Vandalised Petroglyphs in Texas

→ Preserving Our Ancient Art Galleries

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network