Between 1683 and 1834, Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries established a series of religious outposts from today's Baja California and Baja California Sur (Lower California South) into present-day California.

El Camino Real, Spanish for The Royal Road or The King's Highway, connected from north to south - from San Diego to Loreto - the missions, sub-missions, presidios (a Spanish fortified base), and pueblos (stone and adobe communities) over a distance of roughly 600 miles. It was also referred to as the 'California Mission Trail'.

Camino Real became a generic term for any road under the direct jurisdiction of the Spanish crown, but once Mexico won its independence from Spain, this practice ceased. The term "El Camino Real" had its origin in medieval Spain where it was used to distinguish the principal routes in each district as a route of passage for royal orders or royal arms, and patrolled to for safe passage from bandits. Over time, it became a generic term for the principal road between any two major centres.

In Baja California, the Jesuits used El Camino Real as they travelled through the region evangelizing the indigenous population. Generally, existing Indian trails were used as the basis for the new trail, which was cleared for pack and riding animals. The trails in the north of the peninsula were generally better than in the south due to the difficult terrain and the hostility of southern tribes; other means of transport such as sailing were still more attractive.

With the lack of standardized road signs at this time, it was decided to place distinctive bells along the route, hung on supports in the form of an 11-foot tall shepherd's crook, symbolizing a Jesuit's walking stick. Moreover, the missionaries are said to have sprinkled mustard seeds along the trail in order to mark it with bright yellow flowers.

During the 1970's the photographer Harry W. Crosby set out to explore the central mountains of Baja California by mule and pack burros, crossing back and forth over El Camino Real, in a systematic search for rock paintings having been drawn to the art during an earlier expedition seeking the El Camino Real. The El Camino Real expedition led to his publication 'The King's Highway in Baja California' whilst his subsequent expeditions in search of cave paintings, or the 'Great Murals', led to his publication 'The Cave Paintings of Baja California: Discovering the Great Murals of an Unknown People'.

The California missions were generally thought to begin from 1769, but the first permanent mission, Misión Nuestra Señora de Loreto Concho in Baja California, was founded seventy-three years earlier, on October 25, 1697, by the Jesuit Father Juan María de Salvatierra. Over the next 70 years Jesuits founded a further 17 missions along the El Camino Real.

Mission Santa Maria de los Angeles was the last of the missions established by the Jesuits in Baja California in 1767. The site chosen was the Cochimi settlement of Cabujakaamung ('arroyo of crags'), west of Bahia San Luis Gonzaga near the Gulf of California coast. This was only months before the Jesuits were expelled, as King Carlos III of Spain became wary of their growing power, from Baja California.

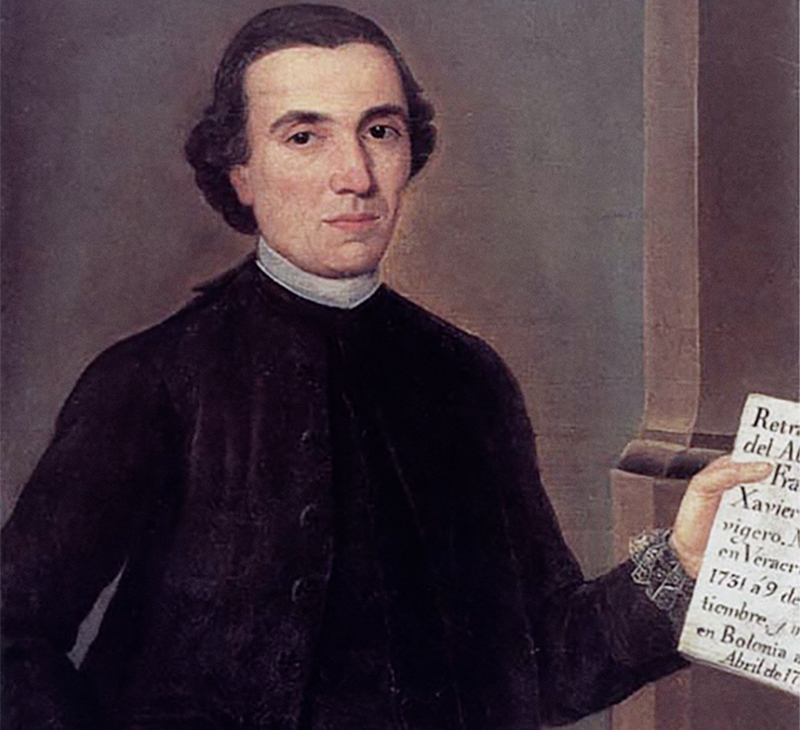

One of the Mexican Jesuits who lived out his life in Italian exile was Francisco Javier Clavijero, who wrote a history of Mexico with emphasis on the indigenous peoples, in particular the Cochimi. 'Historia de la Antigua o Baja California' 1789 in 4 volumes, also reflects on the works of the Jesuit missionaries in Baja California, including Miguel Venegas, Juan Maria Salvatierra, Eusebio Francisco Kino, Juan de Ugarte, Francisco Maria Piccolo, Fernando Consag. English translations were published in San Francisco in 1864 and in Los Angeles in 1938. Father Francisco Javier Clavijero died in Bologna April 2, 1787, aged 56; he did not live to see the final publication of 'Historia de la Antigua o Baja California.'

Another Jesuit priest who studied the Cochimi culture was Sigismundo Taraval, stationed at San Ignacio in 1732. A notable episode while he was at San Ignacio was the bringing of the inhabitants of Cedros Island - home to some of the earliest Cochimi-speaking occupants of the Pacific coast of North America - to the mission. In a relatively detailed account of the islanders' aboriginal lifeways, Taraval presented what were perhaps the earliest speculations concerning the region's prehistoric past.

He left ethnological records of the rock art which he was certain was created by the Cochimi. He remarked that the 'guamas', or shamans, of these people decorated their heads with all kinds of objects and that they would 'placate' the sun by raising their arms to it. Such a pose may be depicted in the rock art that we see today, with the characteristic and dramatic larger-than-life human figures, now called 'monos', sometimes black, sometimes red and black, with arms raised in salutation.

The Great Murals of Baja California are now thought to be the most distinctive art trove in North America. In the 1970's the author and photographer Harry W. Crosby explored the central mountains of Baja California by mule and pack burros in a systematic search for these rock paintings, resulting in his publication 'The Cave Paintings of Baja California: Discovering the Great Murals of an Unknown People'. Indeed, it was Crosby who coined the phrase 'Great Murals'.

In 1993 the Sierra de San Francisco - considered to be the centre of Baja California's rock art - appeared on UNESCO's World Heritage List.

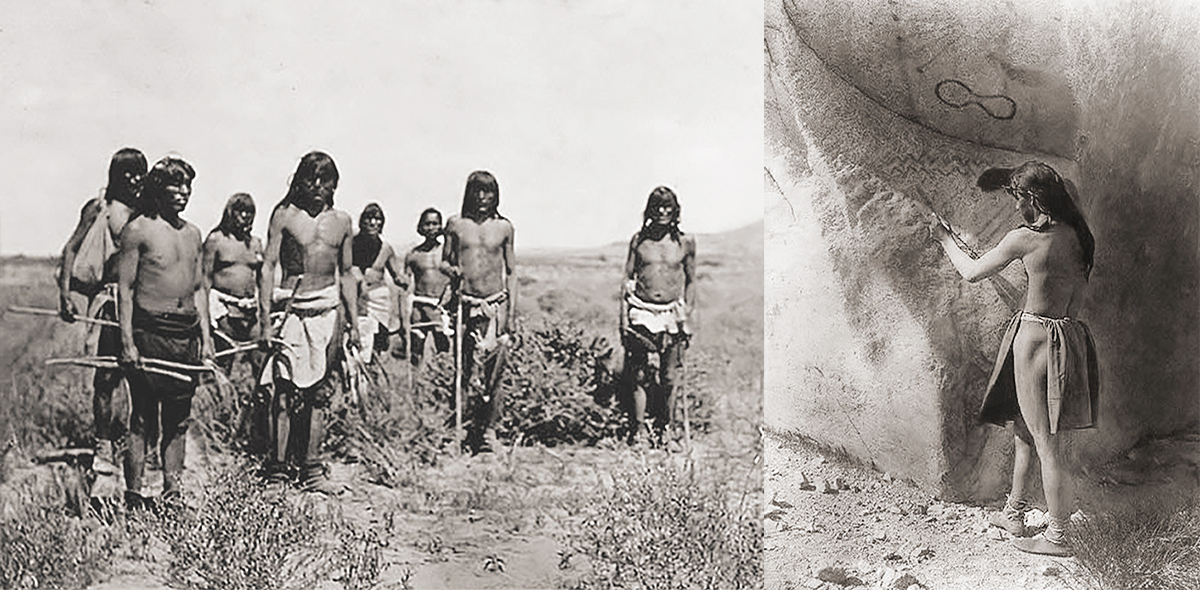

The Cochimi were the aboriginal inhabitants of the central and northern parts of the Baja California peninsula. Two other ethnic groups occupied the peninsula further south; the Guaycura and the Peric. Archaeological research suggests that the peninsula was inhabited up to 10,000 years ago.

The Cochimi spoke a dialect of the more northern Yuman language. It was considered a sister language to the Yuman ethnic group, hence the 'Yuman-Cochimi family'. The Cochimi were hunter-gatherers, leading a prehistoric existence without agriculture or metallurgy. Pottery was used and there is evidence of wooden drums or tablas. Ceremonies and shamanic practices were held. Perhaps their greatest cultural legacy is the cave paintings; the Great Murals of Baja California have been attributed to the Cochimi, although on-going research aims to confirm this assertion.

It is hypothesised that the rock art was produced in the context of shamanic rituals. Indeed, the paintings are a significant statement of the cultural sophistication of a prehistoric people whose material culture was relatively minimal [Schaafsma 1997].

In the 1970's the author and photographer Harry W. Crosby explored the central mountains of Baja California by mule and pack burros in a systematic search for these rock paintings, resulting in his publication 'The Cave Paintings of Baja California: Discovering the Great Murals of an Unknown People'. Indeed, it was Crosby who coined the phrase 'Great Murals'.

In 1993 the Sierra de San Francisco, considered to be the centre of Baja California's rock art, appeared on UNESCO's World Heritage List.

Historical reports reveal how the Cochimi were first encountered by Spanish seaborne explorers during the sixteenth century, then by the Jesuits establishing missions on the peninsula in the late seventeenth century, such as Francesco Maria Piccolo's Cochimi mission at San Javier in 1699. The Cochimi customs and beliefs were recorded in the writings of the Jesuits, such as the works of Miguel Venegas and Miguel del Barco. After the Spanish crown expelled the Jesuits from Baja California in 1768, the Franciscans established further missions on their way north to Alta California. The Franciscans' successors in Baja California, the Dominicans, created the final new mission among the Cochimi at El Rosario in 1774.

These encounters cost the Cochimi culture dearly; epidemics of Old World diseases caused the population to decline dramatically. At sometime in the nineteenth or possibly the early twentieth century their language and traditional culture became extinct. Archaeologists believe that it is now only the rock art that endures.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ America Rock Art Index

→ The Rock Art of Baja California

→ Baja On Film

→ California Rock Art Foundation

→ Baja In Search of Painted Caves

→ Baja Great Murals Gallery

→ Sierra de San Francisco

→ Baja 2018 Expedition

→ The Rock Art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands

→ Color Engenders Life

→ The Rock Art of Arizona

→ The Rock Art of Nevada

→ Coso Sheep Cult of East California

→ Coso Range Rock Art Gallery

→ The Rock Art of Moab Utah

→ The Rock Art of the Oregon Territory

→ RAN - USA Colloquium 2018

→ Removal & Camouflage of Graffiti

→ Graffiti Dates & Names

→ Vandalised Petroglyphs in Texas

→ Preserving Our Ancient Art Galleries

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network