Rock art, an essentially pan-global phenomenon, is one of the great cultural achievements of our early ancestors. Testifying to humankind's imagination and creativity, it constitutes a striking visual aspect of our collective patrimony. Believed to have originated some 40,000-50,000 years ago with Cro-Magnon man, the immediate ancestor of fully modern humans, rock art reflects the beginnings of "our artistic sensibility, of the basic human impulse to communicate, to create, to depict, to influence the course of life" (Clottes 2002:3).

With the exception of Antarctica, where no rock art is found, a preliminary survey from all other continents has shown that "about 70,000 sites of rock paintings and engravings are known throughout the world, with an estimated 45 million images and signs on record" (Anati 2004:2). However, these estimates may be far too conservative considering that Arizona alone houses approximately 6,000 to 8,000 sites. Many of these are of "world-class" quality and are an integral part of the rock art theater of the American Southwest, an area that ranks as one of the great epicenters of paleoart in the world.

The use of the discipline's central term, rock art, has itself been the subject of controversy for some time. Should so-called primitive art be considered "real art"? From a Western perspective, art (often spelled with a capital A) is seen as an embellishment that may have no function beyond the aesthetic. As a superfluous addition to life that is an end in itself and generally of no utilitarian value, it has been appropriately summed up as "art for art's sake."

In stark contrast to this narrow and isolating concept of art, Ellen Dissanayake (1992a:XIX) insists that humans are intrinsically artistic animals and advocates a "species-centred" perspective that essentially declares that art "must be viewed as an inherent universal trait of the human species, as normal as language, sex, sociability, aggression, or any of the other characteristics of human nature" (1992b:169). Because all humans, cross-culturally and over thousands of years, have created and continue to create and respond to various forms of art, it must have been of great importance to them. Indeed, This behaviour had a survival value and evolved to become a psychobiological necessity. Art is not perceived as a "l'art pour l'art" whim, but as "art for life's sake".

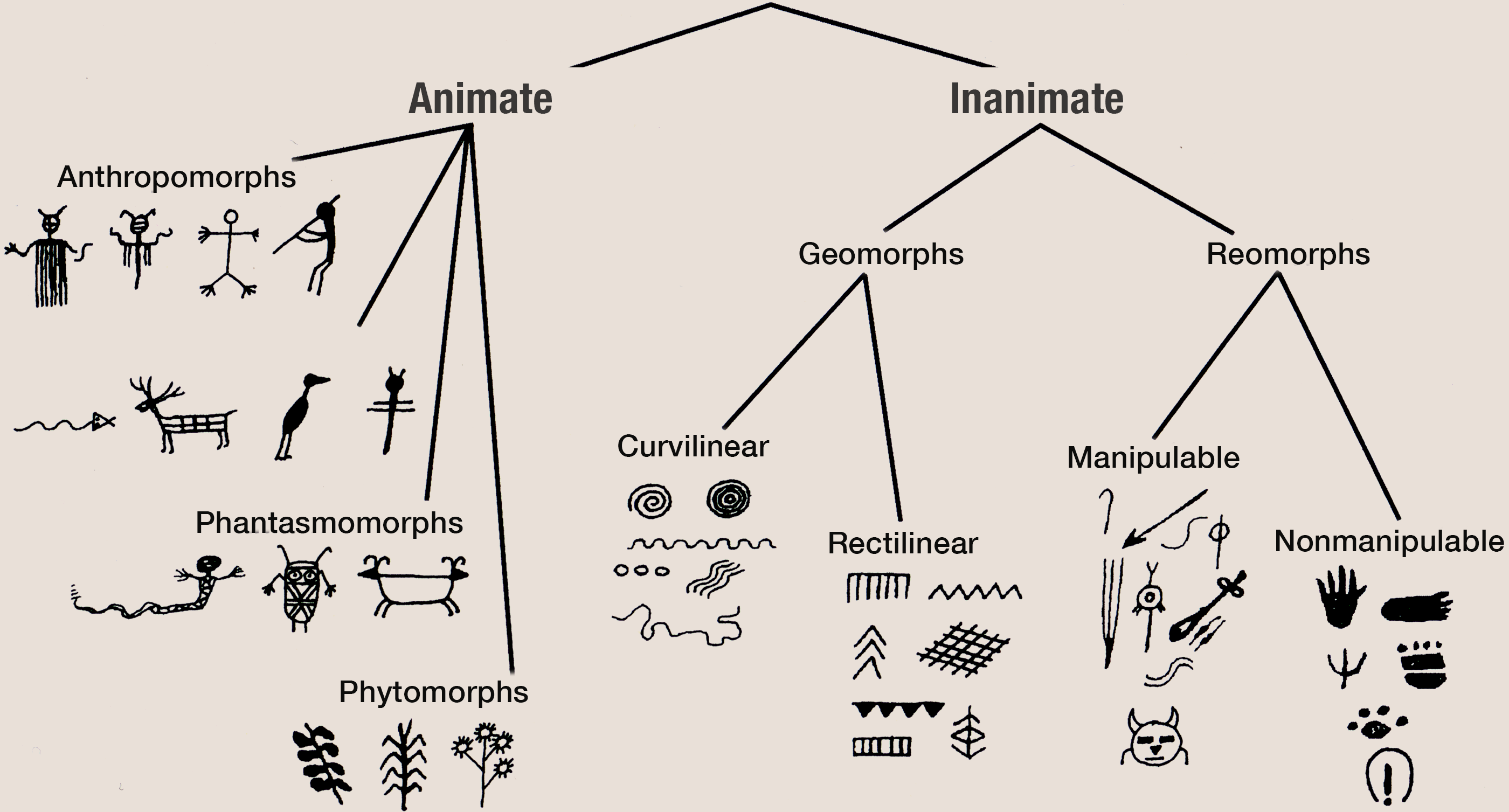

Rock art is defined as man-made markings on rock surfaces produced by means of subtractive or additive processes, resulting in pet,broglyphs, pictographs, and ground figures.

Petroglyphs - carved images - are the most numerous form of paleoart in Arizona. They are found in every region of the state where suitable "canvases" exist. They are made on relatively smooth rock surfaces by direct or indirect percussion. The most prevalent method used is pecking, although images also result from incising, scratching, abrading and drilling. Occasionally, a single design uses two or more techniques. Most early images are now overlaid with a dark coating or patina known as desert or rock varnish.

Pictographs - painted images - are not very prevalent in Arizona. They are usually found in areas with cliff overhangs, rock shelters and caves. The paint, generally made from naturally occurring pigments such as charcoal, red and yellow ochre, hematite or kaolin, is applied in a variety of ways; using brushes, fingers or hands, or by spraying or spitting. To ensure adhesion, organic binders such as blood, urine, tree sap or animal fat are added to the paint mixture.

Gound figures - geoglyphs or intaglios - are made directly on the desert surface rather than on the rock. They are found predominantly in the southwest quarter of Arizona, especially along the banks of the lower Colorado and Gila Rivers. Most are produced by scraping aside desert gravels and pebbles. Sometimes they are produced by compacting the soil by repeated stomping, creating a somewhat sunken image.

Interpretation is the most challenging and controversial aspect of the study of rupestrian images. In order to meaningfully interpret any form of art, the investigator must focus on its maker and attempt to understand his or her cognitive universe, needs and motivations. Because the original creators of prehistoric rock art died long ago, however, the meaning of these images will ultimately remain a mystery. Meaning can, therefore, only be inferred in the form of hypotheses and speculative concepts that will never be testable or verifiable. For this reason, the question of meaning is often avoided by researchers.

There is no universally applicable blueprint for deciphering meaning. There is no simple measurement to reveal the intent of the artist. However, in order for rock art research not to remain a sterile endeavor, efforts must be made to transcend mere description. To this end, a broad spectrum of explanatory ideas have been advanced. It is unrealistic to expect that a single global model is capable of covering a body of art that encompasses such a diversity of images created over hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

All of us see with preconceived notions and biases from our own societies. Visual perception is highly subjective, conditioned by an individual's cultural, religious, and educational background.

Ideally, fathoming the meaning of an image would entail understanding what it meant to its original creators and viewers, but in the absence of any ethnographic insights into most of Arizona's paleoart, this remains an elusive endeavor. Motivations and functions can be gleaned, however, from ethnographic analogy with present cultures and universal features underlying human cognition. Thus, worldwide, we can observe a multiplicity of rock art manifestations which may differ radically in their iconographic and thematic surface details but are anchored in a deep structure of thought that is substantially the same for all human minds. These images are but a universal graphic attempt to communicate, most likely to some perceived supernatural force, humankind's deepest desire for sufficient food, shelter and water, good health, safety, and other necessities related to the survival of the species. As Dissanayake states, art as an evolutionary phenomenon is truly art for life's sake.

With most scientifically based rock art dating methods still in their experimental stage, held unreliable, or essentially discredited, "nearly all of the world's rock art remains effectively undated" (Bednarik 1998:8). Although sophisticated accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon analysis now allows for the possibility of more confidently dating pictographs containing organic residues in their pigments or binders, no comparable approach exists for petroglyphs and geoglyths. Traditional techniques - differential repatination and weathering, superimposition, image content, apparent direct association with other dateable archaeological remains, and positioning of the rupestrian elements on cliff walls - thus remain the most widely favoured in regional investigations. Based on unverifiable assumptions, these indirect methodologies provide only general relative dating clues and hence must be applied with great caution.

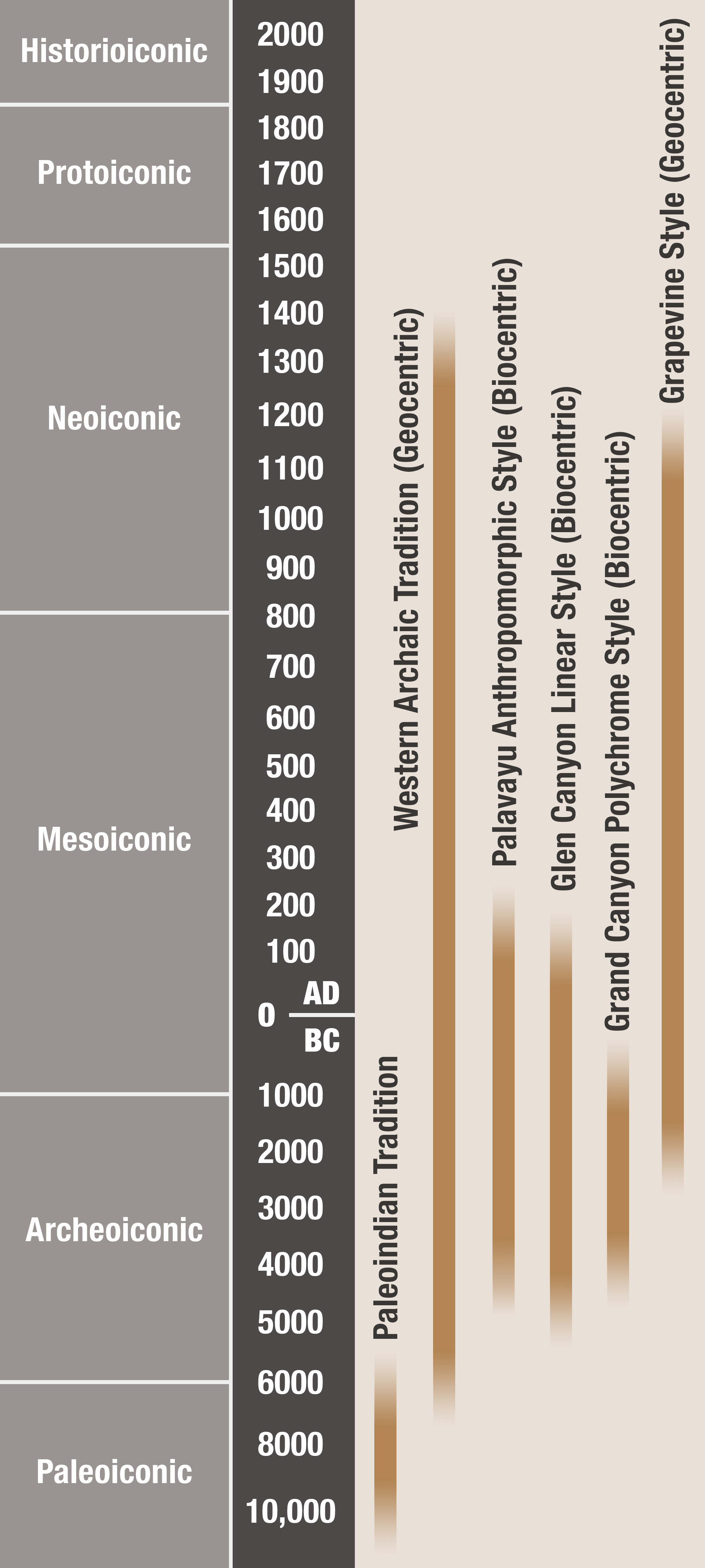

In order to deal with the immense body of Arizona rock art in a reasonably manageable way, the author presents two periods; the Archaic and the Post-Archaic, divided by a somewhat arbitrary time line of 1000 B.C. The temporal framework is then broken down into blocks devoid of cultural affiliations:

- Paleoiconic - 10000 to 6000 B.C.

- Archeoiconic - 6000 to 1000 B.C.

- Mesoiconic - 1000 B.C. to A.D. 800

- Neoiconic - A.D. 800 to 1550

- Protoiconic - A.D. 1550 to 1850

- Historioiconic - A.D. 1850 to 2000

Style as a concept is the primary organizational tool used for all forms of the visual arts. For rock art, style definitions usually include references to recurring similarities of design and motif, technique, distinctness of expression, overall aesthetic quality, artistic attributes and material considerations. Traditions, in turn, are of longer temporal duration, usually embrace multiple styles, and may cut across cultural boundaries. In recent years, however, the notion of style has come under mounting criticism. The perception of what comprises a style is in constant flux, and attributes of a given style are heavily influenced by subjective evaluation. However, in Arizona where petroglyphs far outnumber rock paintings, discarding style as a taxonomic device and analytical tool is not an option.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ America Rock Art Index

→ The Rock Art of Baja California

→ Baja On Film

→ California Rock Art Foundation

→ Baja In Search of Painted Caves

→ Baja Great Murals Gallery

→ Sierra de San Francisco

→ Baja 2018 Expedition

→ The Rock Art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands

→ Color Engenders Life

→ The Rock Art of Arizona

→ The Rock Art of Nevada

→ Coso Sheep Cult of East California

→ Coso Range Rock Art Gallery

→ The Rock Art of Moab Utah

→ The Rock Art of the Oregon Territory

→ RAN - USA Colloquium 2018

→ Removal & Camouflage of Graffiti

→ Graffiti Dates & Names

→ Vandalised Petroglyphs in Texas

→ Preserving Our Ancient Art Galleries

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network