An article by on theguardian.com - Neanderthals dived for shells to make tools, research suggests - reports on a recent study that further clears the common misconception of the Neanderthal culture.

Neanderthals went diving for shells to turn into tools, according to new research, suggesting our Neanderthal cousins made more use of the sea than previously thought.

The study focuses on 171 shell tools that were found in a now inaccessible coastal cave in central Italy, known as the Grotta dei Moscerini, which was excavated in 1949. Dating of animal teeth found within layers alongside the shell tools suggest they are from about 90,000 to 100,000 years ago – a time when only Neanderthals are thought to have been present in western Europe.

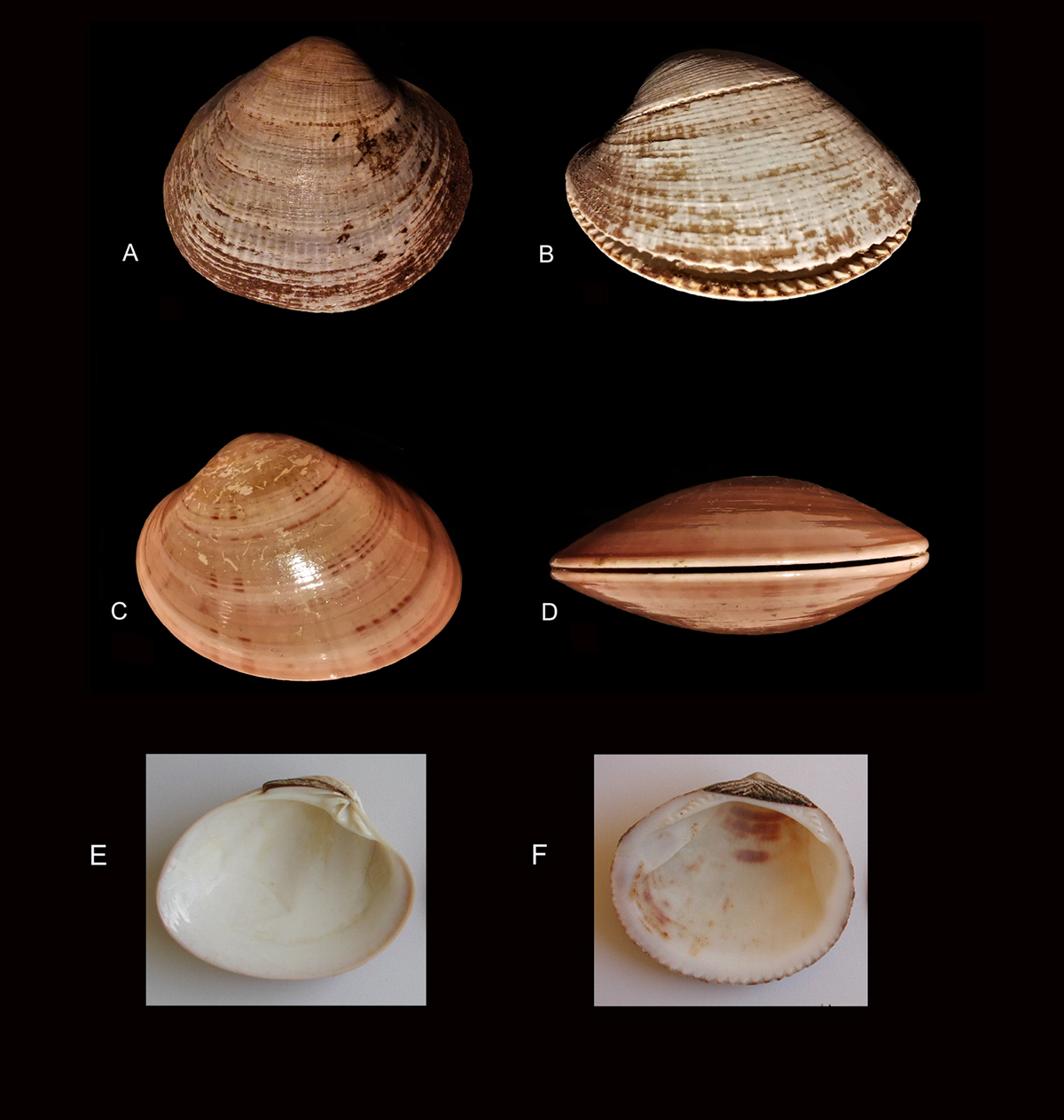

The tools had previously been thought to have been formed from shells collected by Neanderthals from the beach where they had been tossed by waves. But microscopic examination reveals that the shell tools do not show the wear and tear that would be expected from such a fate, such as the presence of barnacles or marks on the shells.

Paola Villa, the co-author of the study from University of Colorado Boulder, explains “In live animals is shiny, in beached valves – thrown by the sea during a storm on the beach – the surface of the valves is opaque and patinated.”

The team say almost a quarter of the shell tools – all of which were made from the shell of a clam known as Callista chione and were probably used as scrapers – show surfaces that suggest they were picked off the seabed, probably with the mollusc still alive inside.

Villa said the findings suggested Neanderthals were collecting shells by diving to depths of about two to four metres: “Callista chione are found in coastal waters from one to 180 metres below sea level. But Neanderthals did not have scuba diving equipment.”

Analysis of the archaeological layers shows the abundance of stone tools varied but was often low – suggesting the cave was sporadically used or not heavily occupied. However, the team found shell tools were more common in layers when stone tools were particularly scarce, with possible explanations including that the Neanderthals only made use of stone when it was close at hand or that they preferred the thin, sharp edge of the shells for tools.

Villa said whether the clams were eaten, as well as being turned into tools, is less clear, although she noted that other molluscs including mussels were collected, possibly above waters, and probably eaten.

The study, published in the journal Plos One, provided a further possibility: the discovery of pumices – lumps of volcanic rock - which were probably collected by Neanderthals from the beach. Such rocks are known to have been used by early modern humans to polish bone points among other uses.

The authors state that this is not the first study to suggest Neanderthals were comfortable in the water. It has recently been found that Neanderthals had “surfer’s ear”, a bony growth in the external ear canal that forms in response to repeated exposure to cold water or wind. Dr Matthew Pope, a Neanderthal researcher at the UCL Institute of Archaeology, agrees: “Taken together, there is evidence to build a case that some Neanderthal individuals or populations might have been diving for aquatic resources. Seeing these behaviours evident in southern Europe, at Grotta dei Moscerini and other sites, long before the established presence of modern humans is further evidence that some Neanderthal populations in Eurasia were on their own independent path to behavioural modernity.”

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 25 June 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 09 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 03 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 28 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 February 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 28 November 2019

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 25 June 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 09 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 03 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 28 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 February 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 28 November 2019

Friend of the Foundation