Preserving Australian Rock Art: the timely recognition being awarded to Australian rock art.

An online article on The Australian website by Victoria Laurie - Art in a distant cave catches the world's eye - reports on the timely recognition being awarded to Australian rock art.

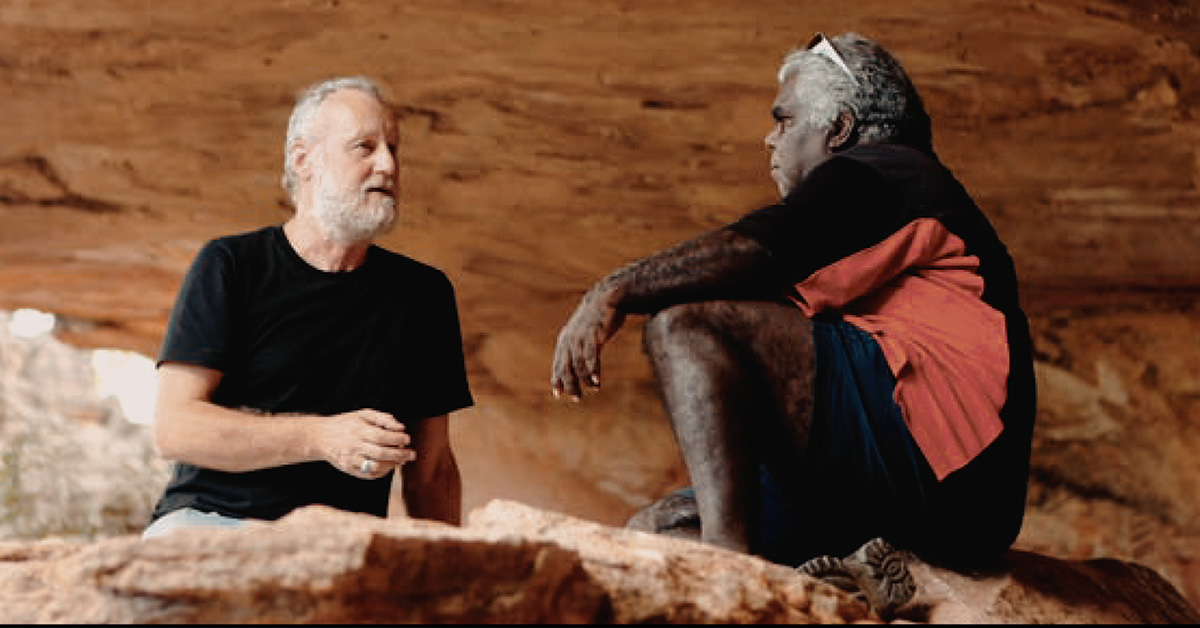

Robyn Mungulu, senior guide with Wandjina Tours, at Cyclone Cave near Freshwater Cove, in the Kimberley. Image: Colin Murty/News Corp Australia

Cyclone Cave, in the remote and Buccaneer Archipelago northeast of Broome, sets the scene, with Robyn Mungulu explaining the purpose of the art:

"When I see the art, I see stories and the people who made them; the mother who went looking for her lost son, poked the eye of the sea with a spear, and it sucked her in".

The Dambimangari Corporation, led by her brother-in-law and Aboriginal artist for the 2000 Sydney Olympic ceremony Donny Woolagoodja, is working with archaeologists to record and date their community's art.

Their efforts are part of extraordinary momentum gathering around Australia's rock art heritage just as threatening clouds hang over heritage laws that have for decades protected some of the nation's most precious works.

This momentum is also being supported by Peter Veth, Professor of Kimberley Rock Art at the University of Western Australia, who is aiming to protect 'one of the largest figurative bodies of art to survive anywhere on the planet'. He states that after decades of semi-neglect and self-funded expeditions by experts and amateurs, Western Australia's largest rock art precincts in the Kimberley, Pilbara and Western Desert are coming under a global spotlight.

The situation couldn't be more timely. The Barnett government has vowed to revise the state's Aboriginal heritage laws into a more 'streamlined' process that assists developers to avoid heritage clearance hold-ups. Dozens of sites have already been stripped of heritage protection.

However, Veth describes how a phalanx of experts, both indigenous and international, are being equipped with philanthropic funds, institutional backing and ultra-modern scientific tools to research and manage Kimberley rock art.

An even bigger ambition is to create the nation's first centre for excellence in rock art, which would require about $28 million over seven years with additional funds of $5m from industry partners.

Moreover, the UWA-based Centre for Rock Art Research and Management has forged global alliances with partners from the British Museum, the Getty Foundation, France's Centre National de Prehistoire and University of California, Berkeley.

Most notable has been increasing engagement with Aboriginal rangers who work across all Kimberley sites, addressing both high-end research and applied management issues concerning the condition, conservation, interpretation and antiquity of rock art.

On an almost daily basis, more sites are found that are decorated with Wandjina, the powerful, wide-eyed spirit forms that constitute recent and contemporary art practice in much of northwestern Australia.

Further east, north of Wyndham and bordering the Joseph Bonaparte Gulf, a massive Kimberley art province is being researched. This dry season, the Balanggarra people will collaborate with UWA and international partners to unravel the complexity of painting galleries, including the far more ancient Gwion Gwion - Bradshaw paintings - rock art, from animal forms to slender hunter figures with weapons.

Veth and colleagues think that earlier dynamic figures from the Kimberley and Arnhem Land have a shared art repertoire and could elucidate the early movement of people across the landscape. Palaeolithic archeologist Martin Porr says he came to Australia from Germany because of the coexistence of ancient rock art and its living cultural exponents. He hopes to explore how these Kimberley insights can help to interpret deep time art elsewhere in the world and how it relates to human origins.

University of Melbourne geochronologist Andy Gleadow is coordinating a multidisciplinary team whose job is to crack the dating code, with input from the Australian Nuclear Science Technology Organisation and other universities.

They combine nine separate but complementary scientific dating techniques to date, for example, mud wasps' nests and mineral crusts laying over the art surface. They may unravel the geological, chemical and biological processes that have preserved some paintings for thousands of years in harsh conditions.

Veth asks why would you enact problematic heritage reforms over a third of the continent when we're on the cusp of discovering one of the global building blocks of human development? This refers to the Barnett government's bid to simplify the process of assessing heritage sites, and hence the ability of developers and miners to clear away heritage impediments. Under current reforms of the Aboriginal Heritage Act, no site in the Kimberley would gain protection as a registered site unless there has recently been religious activity conducted on it. In reality, in the Kimberley every rock shelter and waterhole is likely to have contemporary mythological importance.

As one of the greatest estates on the planet, the rock art and cultural values of the Kimberley must be strategically managed, he says. It will require government and industry to work together with indigenous traditional owners and researchers.

Veth concludes: "Nobody in the Kimberley says they don't want enterprise - they do. They just don't want to sacrifice their heritage, and that's what's bringing all these disparate groups together to defend it. Aboriginal communities, researchers, the philanthropic bodies, we all see that conserving this heritage is critical."

Visit the Australian Rock Art Archive:

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 December 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 29 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 25 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 12 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 24 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 20 April 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 April 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 February 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 January 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 18 December 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Sunday 06 December 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 07 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 December 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 29 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 25 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 12 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 24 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 20 April 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 April 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 February 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 January 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 18 December 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Sunday 06 December 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 07 October 2020

Friend of the Foundation