In the decorated caves of Europe, researchers have observed that the Palaeolithic cave art was designated certain locations within the cave. For all of the art, a spiritual dialogue was being carried out, sometimes for the group, sometimes for the individual. The large painted panels of Lascaux, for example, were thought to be designed for the gathering of a large number of people. But in the European caves there are also many examples where the art was made in unimaginably inaccessible nooks and crannies. This was the dark space for the individual, where the flickering torch gave way to the silent shadows.

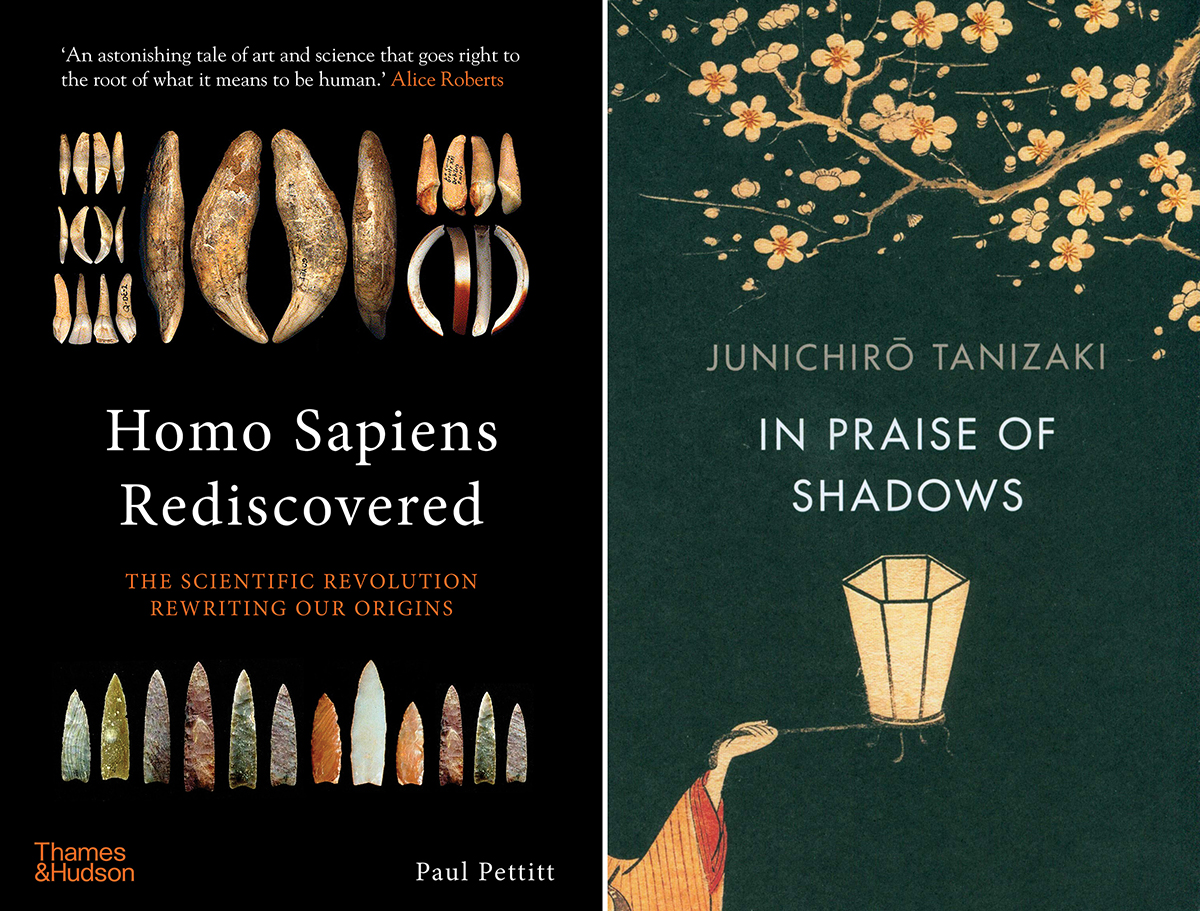

In the new publication 'Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting our Origins' by Paul Pettitt, one of the questions the author asks is why our ancestors were drawn into these dark and dangerous spaces. Caves, he argues, make us hypersensitive to the shadows and shapes; this is where our artistic sensibilities are triggered.

Which brings me to another publication I have just re-read; Jun'ichirō Tanizaki's book 'In Praise of Shadows' written in 1933. Here's an extract:

'A Japanese room might be likened to an inkwash painting, the paper-paneled shoji being the expanse where the ink is thinnest, and the alcove where it is darkest. Whenever I see the alcove of a tastefully built Japanese room, I marvel at our comprehension of the secrets of shadows, our sensitive use of shadow and light......When we gaze into the darkness that gathers behind....though we know perfectly well it is mere shadow, we are overcome with the feeling that in this small corner of the atmosphere there reigns complete and utter silence; that here in the darkness immutable tranquility holds sway.'

Whatever your thoughts are about this artistic speculation and literary juxtaposition, both books are highly recommended.

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 09 August 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 24 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 01 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 March 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 28 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 23 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 31 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 09 August 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 24 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 01 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 March 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 28 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 23 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 31 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 October 2023

Friend of the Foundation