Hipólito Collado1,2,3,9, Sara Garcês1,2,3, Hugo Gomes1,2,3, Virginia Lattao3, George Nash5, Pierluigi Rosina1,2,3, Carmela Vaccaro10, Qingfeng Shao4, Matthias Meyer8, Alba Bossoms Mesa8, José Julio García Arranz9, Diego Salvador Fernandez6, and Hugo Mira Perales7,

1 Instituto Politécnico de Tomar, Portugal

2 Instituto Terra e Memória, Mação, Portugal

3 Centro de Geociências, Portugal

4 Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China

5. Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology, University of Liverpool (Nash@Liverpool.ac.uk)

6. Universidad de Cádiz, Spain

7. Instituto de Estudios Campogibraltareños, Sección 2ª: Arqueología, Etnografía, Patrimonio y Arquitectura, España

8. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Germany

9. Universidad de Extremadura, Spain

10. Universidad de Ferrara, Italy

It is not every day that a team of archaeologists, geologists and aDNA scientists with a keen interest in early prehistoric rock art get a chance to visit, record, sample and verify some of the rock art hotspots around the world. Indeed, researchers at this level tend to find themselves stuck in research corners and remain there until retirement.

Not us! This international team, from six nations – China, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Wales are currently involved in the research of a number of cave and rock shelter sites, some of which possibly hold the key to understanding the origins of art (for want of a better term). Over the past 12 months, the team has been involved in cave research in Portugal, South Africa, Spain, and Wales. The Holy Grail of our expedition activity is seven-fold:

- To discover new sites where intense study is permitted;

- To date early prehistoric art using a variety of dating techniques, in particular, U-series dating;

- To record rock art (painted and engraved) using up-to-date photogrammetric survey techniques; • To sample pigments to systematically evaluate the potential of extracting traces of ancient DNA from pigments;

- To sample pigments for their characterization;

- To analyse pigments for their geological and organic chemical make-up; and

- To create a unique database and synthesis of our work.

Despite the international flavour of the First-Art Team and our associates, we all bring to the table various skill-sets which prove invaluable when prospecting, recording, sampling and analysing rock art. Over the past four years, we’ve been working alongside Professor Qingfeng Shao (Nanjing Normal University) and Professor Alistair Pike (University of Southampton), both of whom deal with U-series dating. Professor Qingfeng Shao is a full member of the First-Art team and has over the years undertaken the majority of the U-series dating, applying recently the laser ablation to improve the results of the dates. The rest of the team is involved in pre- and post-assessments, fieldwork (including site assessment, pigment and control sampling, photogrammetric techniques, contextual analysis of geology and geomorphology) and the production of technical reports and academic literature (Dr Hipólito Collado, Dr Sara Garcês, Dr. José Julio García, Dr. Diego Salvador Fernández, Dr Hugo Gomes, Dr George Nash, PhD. candidate Virginia Lattao and Hugo Mira). Professor Pierluigi Rosina, Dr Carmela Vaccaro, Dr Hugo Gomes, and Ph.D. Candidate Virginia Lattao undertake much of the laboratory work (including processing and preparation of samples and analysis. Also, First-Art team have partnered-up with a science team from the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig (Dr Matthias Meyer and Ph.D. Candidate Alba Bossoms Mesa) who are involved in extracting and analysing DNA from sediments and pigments.

Over the past four years, the team has travelled far and wide, using tried and tested fieldwork and laboratory techniques.

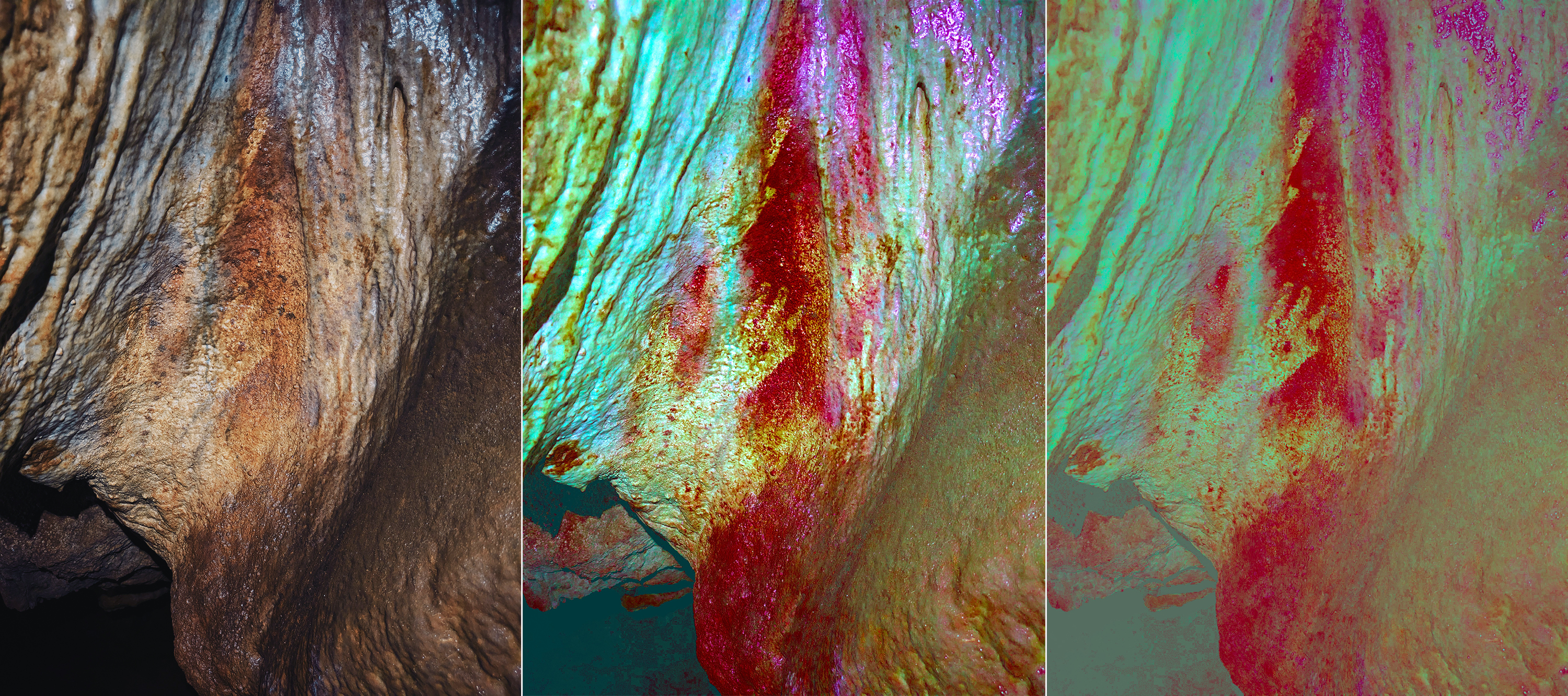

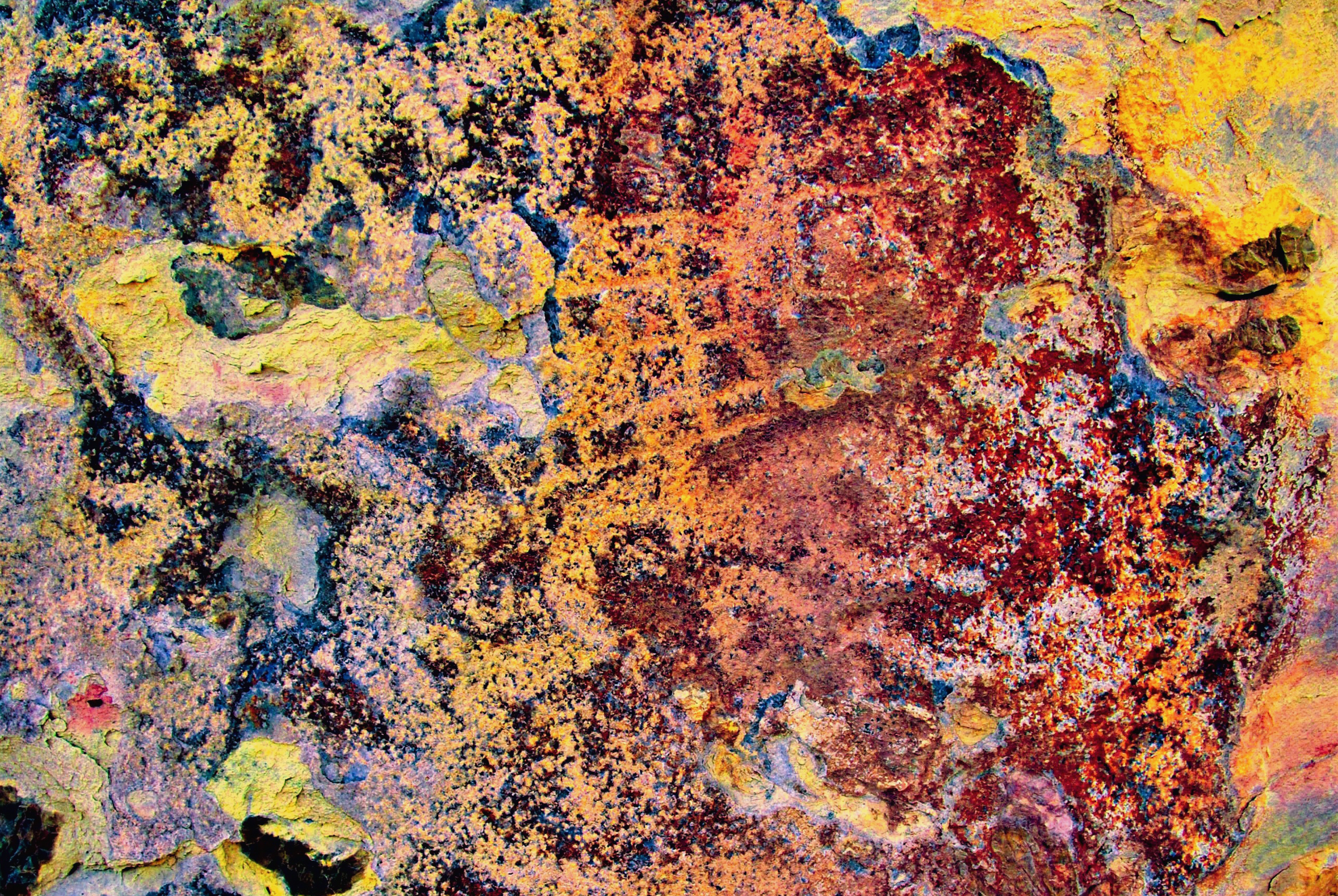

Fieldwork within the core areas of the Iberian Peninsula is beginning to bear fruit with successful dating and pigment analysis results from several caves. For the caves sampled, the First-Art team has managed to push back the date range when Early Modern Humans (EMH) and may be Neanderthals were producing art. Cave expeditions in the regions of Andalusia, Asturias, Extremadura, and Cantabria have clearly shown that EMH were occupying cave sites at least 10kyr prior to current thinking. However, the artistic endeavour is not as we know it! Yes, there are representative figures such aspainted horse, wild goat, ibex, and red deer, but also encountered are abstract motifs, hand stencils and simply, spreads of sprayed [spit] pigment, again using locally sourced iron oxides.

Although the dating of pigment is an essential part of our work, understanding pigment recipes is also fundamental. The majority of the art sampled was painted, using locally sourced iron-oxides of varying shades of red. Laboratory analysis by our team has managed to identify organic constituents within a number of pigment samples that include animal and plant fatty acids in open-air rock art sites but not yet in cave rock art. These would have been mixed with the extracted iron-oxides [powder] to form a paste that could be directly applied to the cave wall or an open-air shelter, using a makeshift brush or simply, applied by a finger (or two). The paste could also have been diluted with fluids, such as water, so it could be applied to the wall using the spit technique (creating hand stencils and spit spreads). In some instances, the same recipes appear to be regularly used on figures and motifs from the same chronology. Much of this art is located on cave walls and ceilings in mainly limestone karst landscapes, where calcite, in the form of flowstone [stal] sometimes develops over the art.

The natural process of stal formation can take many thousands of years to form, and is key in dating the art, using, in particular, U-series dating techniques. Sampling and analysis for U-series dating sometimes provides a minimum date for the application of the pigment. In some rare instances, pigment is sometimes found over flowstone, which can also provide us with a maximum date as well. So far, we have been fortunate to witness on several occasions this sandwich effect whereby the painted imagery is between two calcite flows.

We now turn our attentions to one of our biggest and most exciting challenges – the caves of the Iberian Peninsula. This cave assemblage is found in the limestone karst landscapes of northern and southern Spain, each containing evidence of Neanderthal and EMH activity, be it settlement, or pertinent to us, cave art. In late 2022 and mid and late 2023, the First-Art team undertook expeditions in many out-of-the-way cave sites in Andalucia, Asturias, Extremadura and Cantabria. Here, we thank our regional archaeologist colleagues who allowed us permission to study and sample the caves in each of the four regions of Spain. This recent expedition was funded by the National Geographic Society. The project involved sampling and research of over 30 caves, the majority of which are sited in Spain. This project is considered to be one of the largest in Europe.

Physical and chemical methods used to determine each of the characteristics of the samples taken primarily to understand the nature of potential binders used in recipes involved an array of laboratory techniques including Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) combined with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDX), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and micro-Raman spectroscopy (μ-Raman). These techniques played an essential role in the FIRST ART project. The samples collected by our fieldwork were sent to our laboratory team at the Geosciences Centre in Mação, Portugal for analysis. The team, headed by Professor Pierluigi Rosina and Dr Hugo Gomes got to work on this most precious of material and we await their results. It should be noted that we are in a unique position to have a pigment sampling team, a dating specialist and a DNA team working together.

The FIRST-ART project commenced in 2020 and was initially centred upon three important cave sites: Escoural Cave (Portugal), Maltravieso Cave (Spain) and the Cave of Altamira (Spain). These caves had been previously explored and in terms of the archaeology for each, thoroughly investigated.

Escoural Cave was discovered in 1963, following extensive quarrying activity within the vicinity of the cave. Dispersed over many sections of the cave was an array of painted and engraved art, much of it figurative, portraying bovids, cervids and equids. These animals, constructed of simple brush strokes were painted using iron-oxide pigments. The First-Art team was commissioned to sample the pigments, in order to analyse the constituents. This work ran alongside DNA sampling which was undertaken by colleagues from the Max Planck Institute. At the same time, Professor Qingfeng Shao sampled overlying calcite flowstone deposits that covered various pigment spreads for Useries dating.

A similar approach was used at Maltravieso Cave, where very early dates for rock art were obtained. The cave, discovered in 1951 is located underneath the medieval town of Cáceres (Extremadura). Here, the rock art comprised figurative animal engravings and over 70 painted hand stencils. In 2018 and using U-series dating, a hand stencil was dated to the latter part of the Middle Palaeolithic (at around 67kyr). Could this hand stencil be the action of a Neanderthal artist or the settlement of very early EMHs? In order to conclusively verify this, the First-Art team re-sampled several calcite flowstones in early December 2023. Hopefully, the results will yield a similar date range to the 2018 result.

The cave of Altamira (Santillana del Mar, Cantabria) is probably one of the most famous caves in the world, noted for its exquisite Palaeolithic rock art which was discovered in 1868 by Modesto Cubillas. The rock art included the famous sleeping bison images which were painted on the ceiling within the main gallery, around 150 centuries ago. However, these wonderful figures remained hidden from the public and scientific community until 1889 when they were reported by Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola. Sadly, it was not until 1902 that this remarkable discovery was accepted by the scientific community.

It was announced in 2012 that some of the non-figurative motifs were much older than considered previously. In December 2023, the First-Art team with support from the Altamira Museum developed a new sampling campaign, focusing on calcite flowstone deposits, sediments and human activity evidence. The sampling programme obtained samples for dating and aDNA. This data will allow us to hopefully understand the date range of the art and the people who painted it. It was during this particular fieldwork programme that Dr Hipolito Collado and Dr. Alba Bosson presented some of the results or the First-Art team’s work at a public lecture within the museum.

Since the early 2000s, several members of the First Art team have been exploring caves and rock shelters of southern Britain in order to identify fragmentary evidence of Upper Palaeolithic cave art, especially, in the limestone country that lay south of the Glacial Maximum (between 40 and 15 kyr).

At this time, much of the British Isles (then connected to the European mainland) was covered in snow and ice. Indeed, at the height of the Glacial Maximum, around 20,000 years ago, average summer temperatures would have been 10 degrees Celsius lower than today. A wall of ice, over a kilometre high would have extended from southern Scandinavia in the east, to the Atlantic Ocean via a landmass that is now the North Sea, across the Midlands to the northern hinterlands of the Bristol Channel. Land immediately south of the ice margin would have been similar to today’s steppe tundra of northern Siberia, with permafrost soils and sparse vegetation.

In the British Isles, four limestone karst areas of potential interest are known and include Creswell Crags, The Mendip Hills, The Wye Valley and the Gower Peninsula. All four areas have been extensively explored for archaeology but geo-prospection for rock art is currently at an early stage. In 2003, an Anglo-Spanish team discovered engraved figurative rock art in Church Hole (Creswell Crags). The discovery was arguably the first to be found in the British Isles, although discoveries were made in the early part of the 20th century but were later dismissed due to antiquated ideas on what the Palaeolithic actually was.

Since the discoveries at Church Hole Cave in 2003, members of the First Art team have undertaken fieldwork in caves along the southern section of the Gower Peninsula and the Wye Valley. So far, six caves and one rock shelter have shown promise. One of these caves – Cathole Cave – yielded several engravings within the rear section of the cave, that includes a stylised cervid and a ‘ladder’ motif. Using U-series dating by a team from the Open University, the cervid, possibly a reindeer was dated to between 15 and 13 kyr. Within the same period of exploration, the team also explored the Wye Valley in South Herefordshire. Here, clear undated rock art was found in two caves and a rock shelter. Currently, these sites await further prospection and scrutiny.

However, the biggest story of the past 12 months in the Northern Frontier lands of Europe has been the discovery of paintings in a cave along the southern coast of the Gower Peninsula. This site was discovered by our colleague Dr Barbara Oosterwijk in September 2022. In early 2023, the First Art team, along with Alastair Pike from the University of Southampton, sampled the imagery for pigment analysis and U-series dating. Both sets of data have revealed very exciting results, but more work is needed. It’s a long story which we will reveal when the site has been made secure and the results published. We should also mention that the project was part-funded by the Bradshaw Foundation and a leading conservation charity.

Usually, visits to exotic landscapes such as those in Jordan and the UAE are the result of academics coming together to work out solutions to certain conundrums. Several members of the team had already established a strong foothold in each of the three areas mentioned above; three areas where there are unique early and late prehistoric rock art traditions, all of which deserve more attention. In January and May/June 2022, the two members of the team reestablished protocols with cultural heritage professionals and academics, with a goal to study the painted and engraved rock art in and around Jebel Hafeet and Qarn bint Sa’id (south-eastern UAE), Wadi Rum (western Jordan). Newly discovered rock art was identified in these areas and work is still ongoing. The areas have their challenges, in particular, accessibility and, of course, heat.

Finally, we come to the sometimes-contentious hominin site of Rising Star, South Africa. It was within this cave system that two sports cavers in 2014 discovered remains belonging to Homo Naledi, a new species of hominin. The archaeology comprised burials or what we term internments, a hearth and potential rock art (what we would term as markings). It was initially considered by project leader and paleoanthropologist, Professor Lee Berger that these markings were made by the hands through the cognitive mind of Homo naledi. These discoveries and the claims made by Lee drew a lot of attention from around the world. In the Fall of 2023, Lee contacted the First Art team to establish scientific collaboration that improves the knowledge about the potential Naledi markings in Rising Star.

The last two years have been a busy time for the First Art team and 2024 (and beyond) does not look like a time for taking it easy. The team, along with colleagues from the Max Planck Institute and Nanjing Normal University are starting to organise diaries. Next stop, South Africa, followed by Colombia, Turkey, Croatia, and Spain again, as well as expeditions in southern England and South Wales!

Collado Giraldo, H. (2018). HANDPAS, Manos del Pasado. Catálogo de representaciones de manos en el arte rupestre paleolítico de la Península Ibérica. Mérida (Badajoz): Creative Programme of the European Union / Consejería de Cultura e Igualdad, Junta de Extremadura. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=855736

Collado Giraldo, H. & García Arranz, J. J. (2022). Arte rupestre paleolítico en la cueva de Maltravieso (Cáceres, España). Vol. I: Estudios; Vol. II: Catálogo. Badajoz: Interreg España-Portugal / First Art.

Garcês, S. & Nash, G.H. (eds.) (2024). The Prehistoric Rock Art of Portugal: Symbolising Animals and Things. London: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780429321900