Raj Somadeva was appointed as an Assistant Director to the Sigiriya and Dambulla project of the Cultural Triangle in 1989 and also the Field Director of the Sri Lanka-Germen Excavation project in Ibbankatuva and Pidurangala. He was also served as the same capacity to the SIDA-SAREC funded Settlement Archaeology Project in Sigiriya-Dambulla region.

In 1998 he was awarded as one of the winners of Top Ten award in Sri Lanka under the category of Academic leadership and accomplishment. He was served as a member of the advisory committees to the Director General of Archaeology and the Department of National Archives. In 2015-16 he was appointed to the board of the National Research Council (NRC).

Among his publications are Archaeology of Urban Origins in Southern Sri Lanka (2009), Archaeology of Uda Walava Basin (2010), The Nilgiriseya Survey (2012), Archaeology of Mountains (2014), World Civilizations (in Sinhala) (2016). His publication titled ''Rock Paintings and Engraving Sites in Sri Lanka won the State Literary award for the best academic publication (English) in the year 2013. He won the Vice Chancellor's award of the Kelaniya University for the best researcher in the years 2015 and 2018. Raj Somadeva has published more than 50 research articles both locally and internationally. He has actively contributed to the compilation of the School History curriculum revisions held in 2014. Raj Somadeva is also contributing his service to the Central Cultural Fund of the Ministry of Education as a Project Director of the Cultural Triangle in Southern province. And he introduced Forensic Archaeology to the country. He was invited to carry out the forensic investigations of the Mass grave recovered from the Matale General Hospital premises and his report was well received internationally. Now he is serving as the Consultant Professor of Forensic Archaeology of the Mass grave recovered in Mannar which is the most controversial forensic investigations in the country. Professor Somadeva is currently being serving as a Senior Professor in Archaeology in the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology in Colombo and is a founder Fellow of the Sri Lanka Council of Archaeologists. He is also a life member of the Society of South Asian Archaeologist based in New Delhi.

The first attempt at recording Rock Paintings and Engraving Sites (RPES) in Sri Lanka goes back to the last decades of the 19th century CE. H.C.P. Bell, the first Commissioner of the Archaeological Survey in Ceylon, has reported his observations on the painted rock-surfaces of two sites in the Polonnaruva District (Konnattegodagalge) (Figure 1 & Figure 2) and the Batticaloa District (Arangodagalge in the village Kohombalava ) in 1897. He had observed some 'quaint outline drawings (men, animals, etc.) of the most primitive execution made in white ashes' (Bell 1897:15; see also 1904). Bell is the pioneering force in reporting and commenting on the rock painting sites in the country. Till the end of 1904, thirteen RPES sites have been reported by him. The conclusion he made on the authorship of this tradition as 'the most primitive execution drawn by Vädda (existing aboriginal community) artists' (1904:94 emphasis in italics) has remained as one of the key conceptual formulations among the students of art history and prehistory in Sri Lanka to this day (v. Deraniyagala 1992). The work of C.G. Seligmann and B.Z. Seligmann (1911) on the subject has remained a path breaking venture.

A comprehensive field survey was initiated by a team headed by Professor Raj Somadeva of the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology, University of Kelaniya in 2011 to make a systematic documentation of the RPES in the country. 24 sites have been investigated and documented as a representative sample, out of 57. Majority of the sites reported are situated in almost impassable terrains of the jungle areas. Some of the sites are scattered over territories currently occupied by the aboriginal Vädda community. Due to the practical difficulties in reaching such locations, no one has attempted to visit them after their first discovery and have been neglected for a long period from a deep focus of study.

Early explorers of these sites have made some important accounts on what they have seen, observed and felt about. However their concern to provide locational details was not comprehensive and sometimes lack precision. Some of the village names which appeared in the early documents were not adequately supported to identify the sites during the current field visits. This was due to the disappearance of the old village names/place names with the modern development activities and the government sponsored resettlement programs. Most of the painted cave sites in the uninhabited regions are known by the village hunters and the cattle-herders who used to make periodic visits to the deep jungles; however that breed of men is gradually declining in the rural areas.

At the outset of the project it was thought that the Rock Painting and Engravings tradition in Sri Lanka should be taken into consideration within its contextual meanings. It was recognized that the study of the factors relating to the individual sites such as the (a) locational significance (b) resource potential of the surroundings and (c) accessibility to the critical resources etc. would be helpful determinants in the analysis. The sites reported as belonging to different eco zones and the internal stylistic characteristics among some of them show considerable variation. Whilst the subject matter of the majority of sites shows a marked similarity irrespective of the physiographic context they represent. One of the research issues to be raised in this project involves providing an explanation for the monotonous character prevailing within their broad time-space horizons.

Dating of the respective RPES was a long felt need and a sine qua non in studying the subject. No space was available in the present project for dating because of the extensive effort that had been vested in documentation aspect. The available timeframe and the funding were further constraints providing a comprehensive dating program based on a scientific frame of reference. However the significance of the chronological aspect was not completely ignored in the project. An attempt was made to formulate a comparative chronological scheme using different evidence including both available 14C dates of the archaeological deposits of the sites relevant to the analysis and the valuable anthropological data pertinent to strengthen the argument. The stylistic variations embedded in each RPES register were considered to reflect the varying time periods which were not successive to each other.

Probing the technology of the paintings and engravings was another aspect which the project has taken in to consideration. The painters had used different colours within a very limited spectrum. Firmly cemented coloured pastes found in most of the sites suggest that there was a uniform technique and method involved in the preparation of the substance they used.

Literature survey - Documentation was followed in a number of steps. Compilation of an anthology of the subject, especially collecting published references on Sri Lankan rock paintings was the activity which was carried out at the outset of the project. The aim was to gauge the width and depth of the existing documentations covering the area of study.

Fieldwork - A considerably extensive sample of sites was selected for the field visits. It covered 23 individual locations from five administrative districts enveloping four ecological regions in the country. The selected sample is 39.65% of the total number of the sites so far recorded. Two major steps were followed during the fieldwork in order to maintain the documentation. The first is to make a precise recording of the total register of the image compositions using Cartesian coordinates. The objective of such a mathematical endeavour was to understand the structural relationship existing between each individual image based on the contribution they made to the total composition as single images. The degree of precision of the documentation was maintained through a half meter grid. Images were drawn on A 1 size metric graph sheets on to the 1:50cm scale. The attributes taken in to consideration during the documentation were the (a) dimensions of each image (b) orientation (c) colour (d) technique of the execution (e) nature of the rendering and (f) the state of preservation. Apart from registering the linear measurement of such, the thematic aspects that are related to the landscape context (wind direction, direction of sunlight and wider view of the outside from the cave front etc.) were also documented.

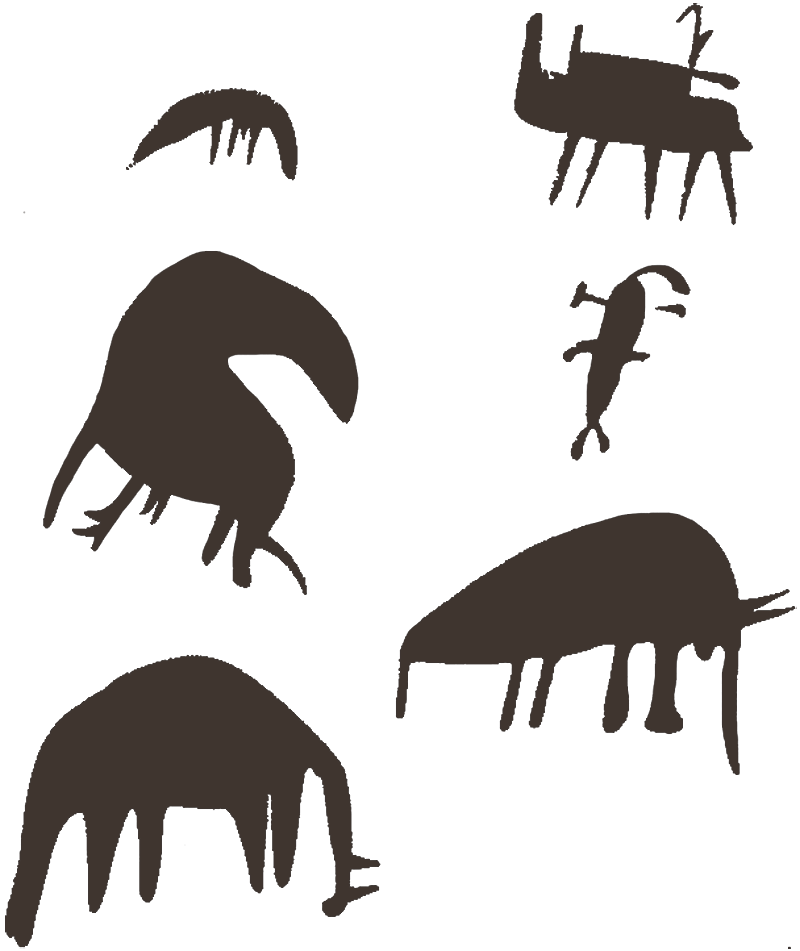

Between the painted sites and the engraved sites, there are some subtle differences in the content, which the painted sites carry a narrative form of manifestation, in the engraved sites it is not so. The geometric markings are confined only to the engraved sites, while the painted sites consist of iconic and symbolic representations. Except for such delicate distinctions, all of our RPES registers comprise simple but, to a certain extent, rationalistic visual expressions. Animals and as well as the association between animals and humans, form the subject matter of the majority of the painted sites.

The pictures that elaborate the way humans carry water (Figure 9), which is narrated in the cave at Hulannuge, could be considered an attempt to express one of the strategies involved in resource exploitation. As Nandadeva (1986) has pointed out in an earlier instance, no hunting scenes were depicted in any of the sites. Instead of elaborating such an aggressive exploitative act, the common expressions are the views which illustrated the friendly associations that existed between humans and animals. The scene of a man standing beside a spotted deer (Axis axis ceylonensis) that was painted in cave number 1 at Tantirimale, and the view of a man who accompanied an unidentified animal (probably a deer cub) (Figure 10) in the same cave are two examples. A single motif of a fish (Figure 11) in our RPES, probably a freshwater species, had been engraved at Dorawakakanda.

Such scenes may illustrate the familiarity that the contemporary communities had experienced after they had turned into a practice of increased exploitation of floral resources (foraging). The picture of a man accompanying an elephant (Figure 12), depicted in several sites gives a rather different meaning. Normally the elephant has no economic value in foraging practice but the depiction of a man & elephant compound may be endowed with a meaning of social significance in the rising contemporary foraging economy. Apart from such figurative images the rest of the content include geometric icons, dots, lines and angular forms (Hakbelikanda & Malayadikanda), intricate linear compounds ( Panama) and circles (Figure 13) (Vettambugala & Malayadikanda) found with them.

Close observations prove that the execution of paintings, particularly the drawing of lines was carried out by using a certain device that would have served the function of a formal brush. The lines of some paintings are thicker than the width of an adult finger and some lines are thinner. A cluster of images in the Hulannuge cave shows the triplication of a single image (see Fig.12 above). A figure of a man and elephant compound has been triplicated placing them adjacent to each other. The notable characteristic of this image cluster is the considerable diversity of its style. The central image depicts a perfect execution in proportion and colour application, but the remaining two images show some degrading stylistic traits in comparison with the former. It appears that the three images were the work of three different individuals. Stylistic differences prove that two persons had made an attempt to duplicate the central image painted by a skilled hand. The closeness of those two to the central image and their immature style suggest that there was a process of teaching and learning of image making by practice at that time. Perhaps the two immature images show the practical work by two students. The idea is further strengthened by the fact that stylistic regularities exist among the images in different sites irrespective of their geographical isolation.

Due to the uncertainty of a precise time indicator that would help to determine the socio-cultural context of the RPE tradition in Sri Lanka, an ambiguity existed about their time-space domain for nearly a century. On the one hand its generic relation with the late Holocene hunter-gatherers (HHG) was emphasized and on the other hand its authorship has been assigned to the existing Vädda community which is said to have a bio-cultural inheritance from the former. It is a commonly held view that the RPEs are a visual tradition that was created by a community which was not disciplined by a 'learned culture' whether it be the work of the HHG or the Vädda community (VC).

The argument developed in the current project does not fall into either of these two extremes but instead, an effort has been made to elaborate the importance of the RPE tradition as a cognitive marker of the local hunter-gatherers and their successors. Therefore it is imperative to observe whether there was any biological and cultural relationship between the HHG and the present day VC in Sri Lanka. The first move towards establishing the bio-cultural continuum between the HHG and the VC is reflected in the work of Sarasin brothers in the early 20th century. Their masterly survey conducted on the ground of physical anthropology and ethnography of the VC is an avant-garde work and it provides first-hand information on the subject (Sarasin & Sarasin 1908). They started their work in the dry lowland area of the country and later moved on to the eastern hinterlands of the intermediate dry lowlands. The reason for this latter geographical focus was;

'....that they expected to find relics of prehistoric man in precisely those areas currently occupied by the Vädda hunter-gatherers on the assumption that the latter constituted the biological and cultural descendants of the former' (Ibid 1,9,10 & also vide Deraniyagala 1992:3).

Sarasin's strong belief on the continuum of the bio-cultural relationship between HHG and VC is reflected mainly in their research methodology which has focused upon studying Vädda ethnography in order to interpret the prehistoric findings they secured from the surface of different localities. The conclusion they made on the anthropology of the VC is worthwhile being quoted here;

'....We furthermore, may already venture to state that the second main period of the Stone age, namely that characterized by the polished stone axe, is entirely wanting in the island of Ceylon, the Veddas having made the step directly from the Old Stone age into the modern Iron Age, which was brought to them....by the Sinhalese, or perhaps by the another people of the Indian sub-continent.' (1907: 190).

Another of Sarasin's publications (1926) has reiterated this idea further and has argued that the lithic remains recovered are representative of the direct ancestors of the existing VC who later borrowed the iron technology from the people who migrated from India.

Seligmann and Seligmann initiated their work in 1908 on Vädda ethnography from a similar theoretical stand as that followed by the Sarasins. They excavated two caves in Bandiyagalge near Henebadda and Mullegamagalge near Ambilinna, which has been occupied by the VC. The objective of those excavations was to search for prehistoric evidence (Seligmann & Seligmann 1911:23). The idea of a biological continuum between those two entities was not again widely discussed until the work of P.E.P. Deraniyagala. He argued on the relationship that existed between the HHC and the VC and states;

'....that strange admixture of ancient and modern psychological assertion, the supposedly autochthonous Vaddha (sic.) of Ceylon, possibly carries some proportion of the blood of Balangoda Man [the author of the Balangoda Culture], but the two differ culturally.' (Deraniyagala 1943: 112).

The notion of the biological ascendancy from hunter-gatherers to the Vädda people was sustained in the prehistoric studies in Sri Lanka for a long time as an implicit theoretical assumption. A study carried out by B. Allchin has commented upon the absence of prehistoric human bones recovered in the country and she thought the reason was that the prehistoric people had followed a similar way of burying their dead as did the Vädda people. Allchin wrote;

'....The almost total absence of human bones at many of the Late Stone Age sites suggests that the inhabitants have followed practices similar to those of the Vädda, who frequently leave the body lying in the cave covered only with leaves.' (1958:200).

More scientific verification on the biology of the prehistoric community in Sri Lanka was appeared in 1960s parallel to the studies conducted on the physical anthropology of the prehistoric human remains recovered from Bellanbandi Pelessa and elsewhere in the country. K.A.R. Kennedy has done a detailed study on the biological and cultural affinities of prehistoric human skeletons found in Bellanbandi Pelessa with the VC (Kennedy 1962). In one of the papers published in 1970s, he concludes that the anatomical similarities which existed between the Balangoda Man (Homo Sapien Balangodensis) (Deraniyagala Sr.1956) and the Vädda people are significant. He states;

'....The prehistoric inhabitants of the island of Sri Lanka....are known from skeletons dating to about 6000 BC. These are from the river site of Bellanbandi Pallassa, and the prehistoric population has been given the nontaxonomic name of the Balangodese.' (sic.).

These ancient people have many anatomical similarities in skeletal features to the tribal hunting people of the island, the Vädda, who are descendants of aboriginal people encountered by invaders from the mainland around the fifth century BC (Kennedy 1972:68). Osteometric analyses of the skeletal remains he observed have shown a long period of population continuity between the late Pleistocene and the modern VC (Kennedy 1980; Kennedy et al 1987). His comparative osteological analysis reveals that the Vädda are not a homogeneous population, and that they do not appear to have been derived from any stock of the historic Sri Lankan population (Kennedy 1965; 1972). Cranial morphometrics suggest that there are strong similarities between the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and the Väddas (Hill 1941; Kennedy et al 1986).

In his later papers Kennedy has pointed out the characteristic of dentition of the prehistoric sample he observed notably the low frequency of shovelled incisors, and infrequent expression of Carabelli's traits and accessory cusps that provide ample evidence to make an anatomical relationship between those two entities (Kennedy 1993). Deraniyagala has made a comprehensive account on the technology and culture of the VC as a part of his Doctoral Dissertation on Prehistory of Sri Lanka (Deraniyagala Jr. 1992). It shows his methodology of analogical reasoning in which the current ethnographical data played a pivotal role. The author's processual approach attempts to bridge the temporal hiatus which exists between the prehistory and the modern Vädda people while making an ethnographic analogy.

'....following account is relevant as a source of analogues for the interpretation of prehistoric subsistence strategy with reference to the entirety of the lowland Dry Zone. The data refer to Veddas in various stages of acculturation, from almost total dependence on hunting and gathering to a subsistence base interwoven with a liberal sprinkling of swidden agriculture.' (Deraniyagala 1992:381).

Diane Hawkey (2002) has argued on the results of her Mean Measure of Divergence (MMD) of dental morphology analysis, that the dental pattern of the Vädda is mostly similar to Sri Lanka prehistoric hunter-gatherers and concluded the Vädda are that of modern-day descendants of the earliest inhabitants (Hunter-gatherers) of Sri Lanka (2002:92 emphasis in italics). Physical anthropological analysis of the prehistoric human skeletal remains has made a strong scientific base to formulate a biological continuum of the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers up to the historic period. It was a commonly accepted phenomenon that the presently existing Vädda are a derivation of a considerably intensive admixture with Sinhala and Tamil population. This acculturation was triggered-off on a mass scale at least around the 13th century when the major cities and the urban and semi-urban settlements in the Dry lowland areas declined. Modern ethnographic observations suggest that the biological and cultural ties they held with the prehistoric hunter-gatherers continued and remained to a certain extent even during the historical period, and therefore they were considered as outsiders in relation to the main population of the country.

The only RPES in Sri Lanka that has been radiometrically dated is Dorawakakanda. Four dates have been assigned to the stratigraphy of an excavation (Perera 2010:14) conducted at the interior of the rock-shelter that reflects a considerably wide range of occupational history:

As suggested by those 14C assays, this place had been occupied intermittently by the HHG since the mid-Holocene for several millennia. It is also interesting to note that there is a series of sites with dates that could be more or less comparable with Dorawakakanda available in Hiregudda of the Sangankallu-Kupgal complex in mid-western Karnataka of South India. A number of engraved stones have been reported from this site and they have been assigned to the Neolithic phase in South India (Brumm et al : 2006:183).

Apart from the dates, the most significant finding recovered from the Dorawakakanda excavation is a collection of stone implements, earthenware shreds together with some variety of millet (Eleusine coracana) grains. The findings of a large collection of fragments of pigment (ochre) suggest that there was an extensive activity of colour processing at the site. Excavators have identified this assemblage as an archaeological indicator of the presence of a new techno-cultural phase which they preferred to coin as the 'Neolithic' (Wijepala 1997). Evidence of a similar techno-cultural leap was reported from Uda Ranchamadama and Haldummulla (Somadeva 2010). These two sites have been radiometrically dated as belonging to the Second millennium BCE. However the Dorawakakanda assemblage is not archaeologically adequate to infer such a techno-cultural transition that had occurred in the late Holocene.

Concerning the dating aspect of the engravings at Doravakakanda, the daunting factor is the absence of any portable engraved object in the excavation that could be compared with the available 14C assay (Deraniyagala 1992:34). The unavailability or nonexistence of any datable object that carries engravings which are comparable with those on the interior wall of the rock-shelter is not a de facto position to avoid the importance of the 14C assay of the internal stratigraphy in order to date the engravings at the site.

Dorawakakanda engravings are not the work of a single period. As discussed in section 1.10.2 above, it was a chaîne opératoire that was authored by several generations of HHG throughout a considerably long period of time. Presumably at least some of the oldest engravings in the total composition might have been executed during the period between 5300 cal BC and 3000 cal. BC (ibid).

In this case it is worthwhile to focus our attention on the artefacts recovered from the excavation of the ancient house floor at Uda Ranchamadama in the year 2009. The material repertoire excavated included a small (2cm x 16cm) pebble (gneiss) which had two flat surfaces. On one surface was an engraved line depicted as radiating from the centre towards the circumference of the elliptical edge of the pebble (Somadeva 2010:99). The context where it was found was radiometrically dated to the 1129 cal. BCE. Earthenware shred excavated from the same context had a similar engraving executed on its exterior surface. The full image of that engraving is not identifiable because of the fragmentary nature of the shred it bore. The latter provided an extension of the use of engravings on the other materials such as clay with differing forms of expression rather than linear motifs i.e. the figurative icons. The modus operandi of those portable engraved objects is obscure but virtually it provides some random evidence that helps to outline a tentative time-frame of the use of such objects.

A noteworthy discovery from the excavation at Uda Ranchamadama is a collection of painted potsherds (red lines on a white surface) and a few pieces of ochre (red and yellow). Some pieces have a smooth surface resulting from rubbing which is a sign of intensive use of colour application. Apart from the use of pigments for colouring earthenware pots, I guess that there was some affiliation between the engravings and the use of ochre. Strata II and IV at Dorawakakanda have yielded 63 pigment fragments and strata VII has also yielded a high count. No strata in the site provided painted earthenware shreds as we once experienced in Uda Ranchamadama. Then what was the purpose of the intensive use of colour pigments at Dorawakakanda? Did the engravers ultimately fill the lines of the engraved images with colourr pigments in order to enhance visibility and contrast? The motive behind the evidence pertaining to the practice of staining the engravings of prehistoric origin is meagre. The lack of physical remains of such paint pigments remaining with the engravings might result from various taphanomical reasons. However, the practice of staining the engravings was sustained among the prehistoric communities in the world at least partially since the late Pleistocene. Evidence of such staining has been reported from the Hayonim cave in Israel. The 'ochre-stained linguistic composition fragment with net-like incisions' recovered was dated to the period between 12 500 -10 200 BP (Belfer-Cohen 1991).

Several constraints had to be faced in the investigation to find out whether there were any signs of pigmentation remaining in the engravings under observation, notable among them the growth of biological constituents (algae and fungi) over the wall surface (Welianga & Osborn 2012). Prolonged existence of moisture throughout the year inside the rock shelter has made a favourable environment for the growth of those microorganisms. The extended moisture conditions and the continuous bio-chemical reactions might have shortened the lifespan of the pigments, if there were any. If so, most probably some of the excavated fragments of pigments recovered from the internal deposit of the rock shelter might be the disbanded colour stains fallen-off from the painted engravings on the adjacent wall.

A remarkable example of colour pigmentation of the engraved images is reported from the cave at Piyangala situated in the Ampara District. One of the clusters of images shown at the northernmost end of this cave was painted in yellowish green colour. Close observations suggest that the use of colour in the images was preceded by the act of carving on the undressed rock surface. The colour pigments still remain there on the lines hewn into the rock to a very shallow depth. The significance of the ochre pieces reported from the interior of the engraved cave in Hakbelikanda, should also be noted. In a synthesis, considering the timeframe of the use of colour pigments in Uda Ranchamadama and the dates assigned to the Dorawakakanda stratigraphy, a tentative chronology could be suggested for the cave, rock-shelter and open-air engraving sites of the HHG in Sri Lanka. Such could be placed in the period when the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers took an initiative towards the intensive utilization of plant resources. A similar transition has been evidenced in the upper Uda Walave Basin where the process has been triggered off in the late Holocene. Increasing engagement with plant utilization had caused a considerable impact on the daily activities among the new foragers while making a fresh behavioural pack. The knowledge they acquired about the landscape while they were walking through unfamiliar areas in the forests for gathering plant resources would have been shared collectively when they flocked together at a particular place.

An analysis of the paintings shows the vital importance of dealing with the information pertaining to the landscape to which they belonged. No hunting scene has been found at any identified RPES in Sri Lanka. Instead of chasing animals and attacking them, most of the animals have been drawn placed close to the human figures. Some human figures have been painted as standing behind the animal. Besides, the other important factor reflected by the selection of animals is that they have been painted associated with human figures. All of them, except the unidentified animal figures show game animals. The index of such animals is extremely narrow but worthwhile to be considered. A spotted deer is explicitly visible with its dotted skin in the RPE register at Tantirimale. The Peacock is another creature that has been found in the paintings in association with the human figures. Previously it was thought that the introduction of the Peacock to Sri Lanka was a late occurrence. But the recent analysis of animal bones recovered from the stratified dated excavations of Mini-Atiliya in the Hambantota District suggests that the Peacock was present in Sri Lanka from a very early date.

There is evidence to show that the mid and late Holocene was critical for the prevailing hunter-gatherers in Peninsular India and Sri Lanka. The initial techno-cultural transformation towards intensive plant utilization was set in motion during this period. It was associated with a series of spinning climatic events. There is an emerging synthesis about a similar techno-cultural transition that had occurred in the mid Holocene in Sri Lanka (v. Somadeva 2010). The visual expression that creates a rather cordial sensation about the human-animal relationship in such paintings could be a metaphorical representation of the advanced hunter gatherers who were more adaptive to exploitation of floral resources.

The continuity of this trend of visual tradition up to the historic period is uncertain due to the inadequacy of archaeological evidence. However some of the graphical forms that appear in potsherds and in some inscriptions belonging to the late proto historic and early historic periods provide some analogous examples which very few icons exist in the RPE tradition remain (v. Paranavitana 1970 xxvi: no. 29, 35, 5g). The influx of new ideas and the propagation of technical capabilities pertaining to the implementation through the rising urban configurations across the Indian Ocean during the later centuries of the first millennium BCE would have constrained any further development of this indigenous visual tradition. Perhaps a very few examples of graphic forms that remain in the early historic period could compare with similar icons in the RPE tradition might convey signs of a long standing memory of the prehistoric practice of image making in Sri Lanka.

Adithya, L.A., 1971. 'Buried finds at Budugala.' Ancient Ceylon 1: 151-165pp.

Allchin, B., 1958. 'The Late Stone Age of Ceylon.' Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 88(2): 179-201pp.

Belfer-Cohen, A., 1991. Art items from Layer B, Hayonim Cave: a case Study of art in a Natufian context. In The Natufian culture in the Levant. O. Bar - Yosef and F. R. Valla (eds.), 569-80pp. Ann Arbor (MI): International Monographs in prehistory.

Bell H.C. P., 1904 - Annual Report for the Archaeological Survey of Ceylon for 1897. 1911 - Annual Report for the Archaeological Survey of Ceylon for 1908.

Browhtning, G. F. R., 1917. 'Some Rock Drawing at Dorawaka in Kegalla District.' Ceylon Antiquary and literary Register, 4(4): 226-227pp.

Brumm, A., N. Boivin & R. Fullagar, 2006. 'Signs of Life: Engraved Stone Artefacts from Neolithic South India.' Cambridge Archaeological Journal, vol.16. no.2: 165-190pp.

Deraniyagala, P.E.P., 1943 - Some aspects of the prehistory of Ceylon, part 1. Spolia Zeylanica 24(1):19-51 pp. 1951 - 'Elephas Maximus the Elephant of Ceylon.' Spolia Zeylanica 26(1).

Deraniyagala S.U., 1956 - 'Some Aspects of the prehistory of Ceylon : Balangoda Culture'. Spolia Zeylanica 28(1):117-20 pp. 1992 - Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective. Colombo: Archaeological Survey Department.

Green E. E., 1887 - Tamil habits of shaving with glass chips. The Taprobanian, 1-63pp.

Gunasinghe, S., 1978 - Album of Buddhist paintings of Sri Lanka: Kandy period. Colombo: National Museum of Sri Lanka.

Hawkey, D.T. 1998 - Out of Asia: Dental Evidence for affinities and microevolution of early population from India/Sri Lanka. Michgan.

Hill, W. C. O., 1941 - The Physical anthropology of the existing Veddahs of Ceylon, Part I. Ceylon Journal of Science (G): 3(2): 27- 144 pp.

Karunarathna L. K., 1985 - 'A Note on Some Primitive Rock Art in Sri Lanka.' In 'Kalyani', Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Kelaniya, 313-315pp.

Karunarathna W. S., 1970 - 'Epigraphy: Dimbulagala.' In Administration report of the Archaeological Survey of Ceylon, 1967/68: G 95.

Kennedy, K. A. R., 1962 - The Balangodese of Ceylon: their biological and cultural affinities with the veddas. A Ph.D. thesis submitted to the University of Berkeley. California, Antropology Department, Ms. 1965 - Human Skeletal material from Ceylon, with an analysis population. Bulletin of the British Museum 2(4). 1972 - 'The Concept of the Vedda Phenotypic Pattern: A Critical analysis of research on the osteological collection of a remnant population.' Spolia Zeylanica 32: 25-60 pp. 1980 - Prehistoric skeletal record of man in South Asia. In Annual Review of Anthropology (1980). 1986 - 'Biological Antropology of upper Pleistocene hominids from Sri Lanka :Batadombalena and Belilena caves.' In Ancient Ceylon 6: 67- 168 pp.

Kennedy, K. A. R., S. U. Deraniyagala, W. J. Roertjen, J. Chiment & T. Disotell 1987. 'Upper Pleistocene fossil hominids from Sri Lanka'. In Amarican Journal of Physical Anthropology 72: 441-61 pp.

Kennedy, K. A. R., 1993 - 'Recent discoveries and studies of the human skeletal material remain of ancient Sri Lankans'. A Palaeoanthropological update. In Festschrift for IP Singh and SC Tiwari.

Lewis, F., 1914 - 'Notes on an Exploration in Eastern Uva and Southern Panama Pattu'. In Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon) NS, 23(67): 276-292 pp.

Manjusri, L.T.P. 1977 - Design Changes from Sri Lankan paintings Colombo, Archaeological Department of Sri Lanka.

Nandadeva, B. D., 1984. 'An Introduction to Rock Art of Sri Lanka', Kalyani, Journal of the Humanities and Social science, University of Kelaniya, 1988.vol.vii and viii, 157-164pp. 1986 - 'Rock Art Sites of Sri Lanka'. In Ancient Ceylon, No.6, , 173- 209 pp.

Paranavitana, S., 1970 - Inscription of Ceylon, early Brahmi inscriptions Volume I, Part I. Colombo: Department of Archaeology.

Perera, N., 2010 - Prehistoric Sri Lanka Late Pleistocene rock shelters and Open air sites. BAR International series 2142, 2010, England.

Pole, J., 1907 - 'A few remarks on prehistoric stones in Ceylon.' Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Ceylon 19(58), 272-81pp.

Punchihewa, G., 1982 - 'The Fascinating veddas'. In The Island. Sunday 14 Feb: 16.

Rambukvella, A. T., 1963 - 'The Nittaewo: The legendary Pygmies of Ceyon'. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon), 8(2) NS.: 265-270 pp.

Sarasin F., and P. Sarasin 1908 - Die Steinzeit auf Ceylon. Ergebnisse Naturwissenschaften Forschungenauf Ceylon, No.4. Wiesbaden.

Sarasiran F., 1926 - 'Stone Age of Ceylon', In Nature.117 (2946):567.

Seligmann, C. G. & B. Z. Seligman, 1911. The Veddas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Somadeva, R., 2010 - Archaeology of the Uda Walave Basin. Colombo: Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology.

Still, J., 1910 - 'Tantrimalai, Some Archaeological Observation and Deduction.' In Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon), 22(63): 87-88 pp.

Weliange W. S & R.A.L. Osborne. 2012 - Some biological aspects of conservation and management of Sri Lankan caves. (Somadeva R. 2012. Rock Paintings and Engravings Sites in Sri Lanka. Colombo: Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology.

Wijepala, W. H., 1997 - New Light on the Prehistory of Sri Lanka in the Context of Recent Investigations at Cave Sites. An unpublished PhD thesis submitted to the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.