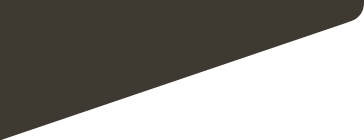

Lascaux is famous for its Palaeolithic cave paintings, found in a complex of caves in the Dordogne region of southwestern France, because of their exceptional quality, size, sophistication and antiquity. Estimated to be up to 20,000 years old, the paintings consist primarily of large animals, once native to the region. Lascaux is located in the Vézère Valley where many other decorated caves have been found since the beginning of the 20th century (for example Les Combarelles and Font-de-Gaume in 1901, Bernifal in 1902). Lascaux is a complex cave with several areas (Hall of the Bulls, Passage gallery) It was discovered on 12 September 1940 and given statutory historic monument protection in december of the same year. In 1979, several decorated caves of the Vézère Valley - including the Lascaux cave - were added to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites list. But these hauntingly beautiful prehistoric cave paintings are in peril. Recently, in Paris, over 200 archaeologists, anthropologists and other scientists gathered for an unprecedented symposium to discuss the plight of the priceless treasures of Lascaux, and to find a solution to preserve them for the future. The Symposium took place under the aegis of France's Ministry of Culture and Communication, and presided over by Dr. Jean Clottes.

Sections have been identified in the cave; the Great Hall of the Bulls, the Lateral Passage, the Shaft of the Dead Man, the Chamber of Engravings, the Painted Gallery, and the Chamber of Felines. The cave contains nearly 2,000 figures, which can be grouped into three main categories - animals, human figures and abstract signs. Most of the major images have been painted onto the walls using mineral pigments although some designs have also been incised into the stone.

Of the animals, equines predominate [364]. There are 90 paintings of stags. Also represented are cattle, bison, felines, a bird, a bear, a rhinoceros, and a human. Among the most famous images are four huge, black bulls or aurochs in the Hall of the Bulls. One of the bulls is 17 feet (5.2 m) long - the largest animal discovered so far in cave art.

Additionally, the bulls appear to be in motion. There are no images of reindeer, even though that was the principal source of food for the artists. A painting referred to as 'The Crossed Bison', found in the chamber called the Nave, is often held as an example of the skill of the Palaeolithic cave painters. The crossed hind legs show the ability to use perspective. Since the year 2000, Lascaux has been beset with a fungus, variously blamed on a new air conditioning system that was installed in the caves, the use of high-powered lights, and the presence of too many visitors. As of 2006, the situation became even graver - the cave saw the growth of black mold. In January 2008, authorities closed the cave for three months, even to scientists and preservationists. A single individual was allowed to enter the cave for 20 minutes once a week to monitor climatic conditions.

For the past few months, the scientific community has been upset by the news of potential threats upon the conservation of the Lascaux paintings. Following the replacement of the machine helping with the climate inside the cave, micro-organisms would have pervaded the environment and no efficient response would have been found to block their progress, thus threatening the conservation of paintings and engravings.

Presided by Jean Clottes and under the aegis of the Ministry of Culture and Communication, the symposium was organised in three sessions, besides a first introductory one. The sessions were centred about three themes directly connected with the problems identified: the environment (i.e. the geological, climatic and physical-chemical conditions for the biological dynamics in the cave); the micro-organisms (the micro-biological dynamics themselves) and the relation between conservation and the public (a central problem in heritage management).

Each session included several presentations on the state of the art, followed by a debate, for which experts from different countries and specialities were invited: these offered a first comment on the presentations, before the debate was opened to a larger audience of over one hundred researchers.

The seminar was introduced by Jean Clottes, who set up the framework of the discussions: transparency, an open clear and international debate, aiming at reaching useful recommendations concerning the problems identified. It is not so frequent that such a framework of debate is set up in order to face problems and contradictions in heritage management, some preferring to simply offer 'criticisms' without any alternatives, often ad hominem and polemic. Science is something else altogether, though, and this symposium was a demonstration of it.

Marc Gauthier, the president of the cave's Scientific Committee, presented the history of research and the ongoing work and principles of the 25 members Committee, which are focused on clear short and middle term objectives (to treat the disease and to identify its causes) with the ability to act fast. Afterwards, Jean-Michel Geneste, director of the Centre National de Préhistoire, presented an overview of the main phases and events in the conservation of the cave, after its discovery in 1940.

Globally, we thought that the discussion was clear and quite open, with the presence of several researchers that had, in a serious and firm way, criticised the action of the Scientific Committee. This enabled the participants to identify the axes of contradiction, but also those of convergence, an aim which must always be that of debates among scientists.

To start with the convergences, all speakers agreed to the need to give priority to the treatment of the disease. They considered that the irruption of white organisms, and later on of black ones, were the consequence of the change of the acclimatising machine, introduced in 2000 (some considering it as the main cause, whereas others judged it as a catalyst).

As for the contradictions, these were centred first in the account of the process leading to the decision to change the machine, some willing to concentrate the discussion on this point, before discussing the possible solutions for the future. One would argue that even if it is always important to assess the processes and to identify the persons responsible for past errors, too much time seems to have been spent on this which would have been better used on a discussion of the future.

In any case, the three thematic sessions enabled the participants to assess the state of the art and to define a frame of alternatives.

The session on the geologic and climatic environment was lead by J. Delgado Rodrigues, with the presentation of the hydrogeologic (Roland Lastennet) and climatic (Philipe Malaurent) contexts, as well as that of an excellent virtual model (Delphine Lacanette). These papers allowed us to understand that the atmosphere regeneration machine set up in 1957 needed to be replaced, due to its ageing, by an identical one, although in the end this was not the case. It also became clear that the succeeding problems of conservation of the cave (the 'white disease' since 1955, the 'green disease' in 1960, white organisms since 2001, soon followed by black ones) were always caused by previous anthropic activity. This session was completed with a presentation on the conservation of the Altamira cave, which made it clear that the efforts devoted to Lascaux have no match elsewhere. The debate was widely participated in and enlivened by the audience (more than by the invited experts, including myself) and it ended so to speak without a distinct conclusion: whereas the speakers centred their interventions on the need to establish a machine to recover the climatic equilibrium prior to 2000, most of their critics were focused on the identification of responsibilities concerning the errors made in the past.

In the second session the central and most productive discussion of the symposium took place. It was on the Lascaux micro-organisms and was directed by Robert Koestler. Isabelle Pallot-Frossard and Geneviëve Orial presented the micro-biological context and the strategies chosen to control it (biocides and repeated actions, more than climatic management and cleanings), whereas Claude Alabouvette detailed the microbiotic ecology (stressing the augmentation of micro-biological diversity in the zones affected by anthropic activity). The work carried out at Lascaux was compared to the efforts of conservation of mural paintings in Japan (Takeshi Ishizaki). With this debate, it became clear that, for the hydrogeologists and climatologists, the main paradigm seems to be the recovery of the equilibrium prior to 2000, whereas for the microbiologists this is not possible, the aim being the search for a new equilibrium. The acceptance of the irreversibility of changes, as well as of the augmentation of diversity with each human intervention inside the cave, were the basic ideas of this discussion, with a proposal to look into areas less affected by the works, as the Shaft, for species long gone elsewhere that might thus be re-introduced. The contradiction between strategies to diminish (as suggested in the first session, but also by some in the second one) or to monitor the micro-biological activity (as proposed in the second session) thus became the heart of the discussion.

The last session, on the conservation of the painted caves and their wider knowledge by the public, introduced by a presentation on the Cantabrian caves and the risks they face (by Roberto Ontañon Peredo), not only stressed the technical dimension of the issue, but also the exemplary character of the Symposium. It is quite encouraging to see that, confronted with a complex and highly visible situation, the scientific community is capable of expressing itself in a forum, without hiding its differences but also without sticking to these as an aim in themselves. The presence of various experts, French or not, working in French and other painted caves, was particularly positive.

The overall conclusions of these two days are that, first of all, they were an exemplary exercise of transparent scientific seriousness, with the presence of the people currently in charge of the scientific management of the cave and of their academic opponents, in a context very efficiently coordinated by Jean Clottes. This is an example which unfortunately is not so frequent to find in other international contexts. Lascaux being a site of major cultural relevance, it is very positive that the Symposium should have been participated in by the scholars truly interested in its safeguarding, whichever opinions they might entertain. The presence of people heading many international organisations, from ICCROM (Mounir Bouchenaki, who rightly considered the symposium as an exemplary event) to UNESCO's World Heritage Committee, reflected such a reality. One wishes that, following this symposium, a future Scientific Committee (already announced by the Minister of Culture) should enlarge the diversity of the expertise (in particular geology) and act mainly with the aim to find new equilibriums based upon the growing diversity of life (as suggested by the microbiologists) rather than attempt to limit the micro-biologic diversity and to recover a long lost ecologic equilibrium. It is also desirable that the international organisms that were present might contribute in an active way for this purpose.

Luiz OOSTERBEEK

Secrétaire Général de l’UISPP (Union Internationale des Sciences Préhistoriques et Protohistoriques / Secretary General of IUPPS (International Union of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences)

The Symposium "Lascaux and preservation issues in a subterranean environment" has generated huge interest, including in the press: out of the 267 registered participants, 21 were journalists. It has also sparked international interest: other than France, seventeen countries from all continents were represented (South Africa, Germany, Australia, Bermuda, Brazil, Ivory Coast, Spain, United States, Italy, Japan, Morocco, New Zealand, Portugal, Czech Republic, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Zambia).

The Symposium purported to be "open", since anyone could register on-line and freely participate if they wanted to. The sheer number and diversity of participants show that it was truly a great success. The sessions (including debates) were perfectly bilingual (English and French), thanks to simultaneous translation.

After these two particularly rich and dense days, my synthesis will focus on three main points: the development of the Symposium; the official announcements and main results; recommendations for the future.

Firstly, I would like the Presidents of the sessions and the participants to excuse my stringency regarding the schedule. It had to be strict and as such it was. Contrary to what happens in most meetings of this type, we began each session right on time and all communications remained within the given time frame. This was a necessary condition so that the debates could last just as long as the presentations, whether questions were asked on all topics or diverse opinions were shared and discussion then followed. I would like to thank wholeheartedly all participants for their consented efforts. In fact, each person took it so much to heart not to exceed their half hour of communication that we were left with extra time (approximately one hour and a half in total) for the debates...

The presentations, which can be viewed on-line, were focused on the main elements of the preservation of Lascaux and the decorated caves, as well as on the history of Lascaux, the problems faced, measures taken and the current condition of the cave. Our colleagues from other countries, either speakers (Japan, Spain), or expert special guests (South Africa, Germany, Australia, United States, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Portugal, Czech Republic), brought valued comparisons and shed different light on the topic. In fact, if the preservation of cave art is a shared issue and if there are so many threats to this essential heritage, there are many problems and solutions and we can only learn from each other.

The many accounts given during and after the Symposium prove that the high quality of communication, along with the freedom and richness of the debates were recognized and appreciated. This meeting therefore satisfied its objective. All the facts regarding Lascaux were clearly presented, including the mistakes made. The debates went as planned, without concession or stonewalling, in complete transparency, whether it was with the decision-making process, the events which occurred, analyses carried out, obstacles or difficulties faced or perspectives for the future.

If it is obvious that not everything has been settled, that the sickness is not yet cured and that the Symposium could not bring a miracle cure, we can only hope that the misunderstandings which may have existed about the events of the last few years will be cleared up for those who really care about one thing: saving Lascaux.

Either at the beginning of or during the Symposium, Mrs Christine Albanel, Minister for Culture and Communication, and Mr. Michel Clément, Director of Architecture and Heritage, made several very interesting, concrete announcements regarding Lascaux. During the communications, particularly those from Drs. Marc Gauthier and Jean-Michel Geneste, we also found out that certain interesting decisions had been made and that projects were underway.

The first of these announcements, which set the scene, was that - unsurprisingly... - Lascaux is considered by the Minister for Culture as a major priority, in such a way that money is no object for research and preservation. Such an announcement is so rare, in whatever country, that it must be highlighted.

The second concerns the Scientific Committee of Lascaux, whose mission will finish in a few months. A tribute was given to its President, Marc Gauthier, and to its members who have been striving to save the cave under very difficult circumstances. This committee, where interdisciplinarity should be the rule, will be re-established in May 2009. It will be even more open, more specialized and more independent. In particular, it will be separated from the steering Committee made up of administrators, naturally while maintaining communication between the two so that no efficiency is lost.

A laboratory-cave will be selected, among several possibilities in the Dordogne area of France, in conditions very close to those of Lascaux. It will be used for experimentations in natural underground settings; these are essential but cannot be carried out in the decorated cave without risk. The results of these procedures will be largely used to try and solve the problems faced at Lascaux.

The Lascaux cave itself has been recreated in 3D. The simulator re-creates its conditions, its morphology as well as its climatology; the problems can therefore be sorted out. It is obvious that these two methods (laboratory-cave and simulator) combined will greatly help in understanding the phenomena and in making decisions.

Last but not least, the long-awaited "sanctuarisation" of the Lascaux hill will finally be achieved. The replica (Lascaux II) should join the valley and roads and car parks should disappear from the hill. This is a full-scale project, for which there will be a collaboration with the local communities (Commune and Département).

All specifications about the condition of Lascaux have been communicated. Marc Gauthier told us that 14 painted or engraved animals (out of around 915) have been affected by the black marks, in the right-hand side of the cave. This is still too many and any adverse effect on the works of art in the cave, whatever it may be, is sorely felt by those who love it, i.e. all of us. However, we are far from the cataclysmic announcements we may have heard or read. No, the frescos of Lascaux are not "condemned" and the cave is not in "danger of death"!

Finally, communications and discussions have enabled us to experience first hand the complexity of the problems faced, along with - in this fragile and vulnerable setting - the difficulty of work conditions and decisions to be made, often in an emergency.

Comparisons have repeatedly been made with medicine, concerning diseases that Lascaux suffers from or has suffered from. It is true that all those who know the underground setting well know that it behaves just like a living organism, with its adaptation and self-regulation abilities or even the ability to regenerate when certain aggressions and changes remain within certain limits. To refer back to this comparison, it is necessary to adopt the most basic saying used by medical doctors, that of the Hippocrates oath, Primum non nocere.

Transposed to the actions in the cave, this implies two main principles: never directly touch fragile decorated walls; run impact studies before the implementation of any new curative policy. In the right-hand side of the cave, we know that the surfaces are crumbly and that any brushing action, even with a very fine brush, will lead to a loss of substance. Such actions are to be forbidden in the decorated areas, since they will cause irreversible damage and will have unpredictable results (infestations can occur again).

The impact studies to test the proposed therapeutic methods, rightly recommended by UNESCO, must be the rule. Some of them can be conducted in a laboratory, but the creation of the laboratory-cave described above would greatly facilitate these studies.

Microbiologists have repeatedly insisted on the fact that spraying biocide can have harmful secondary effects, for example in eliminating the microorganisms which can limit the proliferation of harmful mushrooms, or even in creating organic elements or detritus that some can feed on.

Among the practical measures, it has been suggested (R.-J. Koestler) to re-install the airlock - known as the Bauer Airlock - isolating the right-hand side of the cave from the Hall of the Bulls and the Axial Gallery.

As a logical follow-up to this Symposium and in keeping with its open and interdisciplinarity spirit, one can hope that there will be more communication between specialists and that this will be made easier, either on a personal or institutional level. The vast amount of information collected must be correlated, which presents the problem of an improvement of collaboration systems between specialists and of data management. To avoid the recurrence of misunderstandings, I suggest a health report of Lascaux be established every six months or once a year, and be made available to the public. Moreover, it would most definitely be favourable to plan for the organization of another Symposium in three years, so as to evaluate the situation regarding actions which have been taken in the meantime and their results, which we all hope to be positive.

Lascaux is the tragic illustration of human errors, when fluctuating age-old equilibrium is suddenly broken. Efforts must now be concentrated on the future, in coming out of the other side of the crisis that began a few years ago and to find a new climatic and biological equilibrium, never again that which has for a long time prevailed but still one which will ensure the durability of the paintings and engravings.

Good can result from something bad. Our Spanish colleagues have told us that they benefited from the precedence of Lascaux's problems in order to make decisions regarding the management of Altamira. Furthermore, thanks to the presence of our colleagues from other continents, specialists in other cultures and in other types of rock art, we have been able to widen the conclusions to be drawn from this crisis to other types of rock art sites worldwide.

Rock art as a whole is one of the most important cultural heritage assets in the history of Humanity. Lascaux is certainly one of its jewels, but the most humble of the decorated sites is a witness of ancient cultural beliefs and practices, and therefore it must be protected. Lascaux strongly reminds us of the reasons why preservation is a necessity: above all to limit the effects of human activity on any decorated sites, and on their surrounding environment. That is the main condition for their survival.

Jean CLOTTES

President of the Symposium

→ France Rock Art & Cave Paintings Archive

→ Chauvet Cave

→ Lascaux Cave

→ Niaux Cave

→ Cosquer Cave

→ Rouffignac Cave - Cave of the Hundred Mammoths

→ Bison of Tuc D'Audoubert

→ Geometric Signs & Symbols in Rock Art

→ The Paleolithic Cave Art of France

→ Dr Jean Clottes

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network