The practice of age-old beliefs, ceremonies and stories has nowadays become rare in the world, and the most quoted examples of its continuation in rock art literature are from Australia and Africa. Until very recently, Indian rock art, too, was believed to have become a static cultural phenomenon, frozen in time. But, during my work in Central India, I found that traditional ceremonies along with stories, followed since time immemorial, were still taking place in various painted shelters at auspicious times of the year. The Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh examples (and no doubt elsewhere) thus give an unexpected new dimension to Indian rock art. In most of central India, rock art sites have been reused for modern religious purposes and many have been transformed into Hindu sanctuaries, sometimes defacing or completely destroying the ancient rock art motifs in the process.

Even if many images remain mysterious to us, India in general, and in central India Chhattisgarh in particular, is one of the few places in the world where the perseverance of traditions may permit us to understand the meaning, or some of the meanings, of diverse motifs.

A major part of south Chhattisgarh was known, in ancient times, as Dandakaranya, while the north was called Dakshina Koshal. It was mentioned in the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. Between the sixth and tenth centuries AD various rulers held power. In the medieval period, the region south of the Vindhyas was Gondwanaland, and Chhattisgarh was part of it.

Since 2014, we have been working on the rock art in the State of Chhattisgarh, we have documented sixty-three painted shelters, most of them in deep jungles and forests, which cover over 44% of the surface of the State. We were guided and accompanied to the sites by local Forest officers and by tribal men from the nearest villages. As could be expected, we saw traces of modern sanctuaries and ceremonies in a number of painted sites (Figure 1). We also noticed modest deposits that seemed to be in direct relation to the paintings.

The subjects represented are: animals, humans, and geometric signs. Most painted shelters have animal representations. Bison, bulls (Figure 2) and the most common ones are cervids with stags, does, deer and blackbucks.

Humans are plentiful but less varied than in other rock art areas of Central India. A great majority of humans are shown involved in various activities or carrying bow and arrows. The most common case is dancing in a row, with people close together holding arms (Figure 3), raising them or putting their arms on the shoulder or waist of the person next to them. Other daily life activities are also represented, like carrying loads. Hunting scenes are quite frequent, like an archer shooting at a deer.

We have noticed hand and feet representations, that mostly include handprints (Figure 4), but occasional hand stencils occur, when the hand is applied against the wall and paint is blown onto it and its outlines; when the hand is removed, it appears in negative (Hamtha) (Figure 5). Sometimes feet - isolated or in pairs (Figure 6) - are represented. In some cases (Siroli Dongeri), they seem to have been made by different persons applying colour on the soles of their feet before printing them onto the rock surface, the person lying on the rocky ground or perhaps using somebody?s help.

One of the essential characteristics of Chhattisgarth rock art, particularly in the north, is the number and complexity of geometric figures or signs (Figure 7), Ushakothi 1 being the most important site we saw for signs. They include dots, which may be in a cloud or be part of complex motifs; parallel lines; zigzags (some of them could be snakes); circles and roundish motifs, often with an inside pattern which may be simple (a cross, another circle) or quite complex; numerous quadrangular designs with a drawing inside; other complex designs (Figure 8). Tribals believe that their ancestors' souls reside in those geometrical signs and from time to time they come in their dreams to ask them to fulfil their wishes.

Rock art making in Chhattisgarh goes from the Mesolithic (perhaps 8,000/10,000 years BP) to fairly recent times with some typical images for each main period. So far we have no radiocarbon dates for the art, nor any other absolute dates. Our ascriptions were thus done provisionally from the style of the representations.

Perhaps because of their remoteness and of the prevalence in Chhattisgarh of tribes that have kept their age old traditions, the number of painted sites where we found undisputable traces of recent ceremonies (Figure 9), offerings and religious practices has proved to be unexpectedly high. This contrasts with the rest of the world where nowadays such practices have either entirely vanished or have become exceptional as in Aboriginal Australia.

The offerings made by the local visitors are nearly always the same (coconut, incense, glass bangles, sometimes ceramic statuettes), identical to the ones one can see in Hindu temples, as well as the vermillion colour that has kept its symbolical and powerful meaning as establishing a relationship between humans and gods.

Handprints thus establish a direct relationship between this world and the next. They are perceived as protection. We shall give one example with handprints found both in the shelters with rock art and on the walls of houses. They are very common in the tribes. They may be made on different occasions such as marriages, new crops, and any festival. For example, for the protection from ghosts Murias will print hands in a row all around the walls of their houses. Among the Gonds, when somebody dies, family members will make a paste made of rice flour - which stands for the colour white - and of turmeric (for yellow) to which they add vermillion powder for red. They will then make handprints inside and outside their homes and also in the shrines of their local gods. The aim of such ceremonies and handprint making is to ensure that the soul of the dead person will rest in peace.

Some animals seem to have a particular role and to be the subjects of stories. For example, spectacular big goh or lizards (Figure 10), represented in the Kabra Pahar rock art, have a bad reputation with the Gonds. It is said that since that animal is cursed, putting it into the house of an enemy can cause him a mishap. If nothing is done by a shaman to prevent the mishap, members of the house who see it will become ill, their arms and legs will dry up (like a lizard's limbs) and bellies will become distended. This specific disease is called Haileniyam by the Gonds. Since merely catching sight of a lizard is considered such a bad omen, the person who does must immediately rush to a shaman's to counter the curse. The shaman neutralizes it by performing a ritual which requires the cursed person to bring a cockerel and a coconut, and to sit facing west while the shaman holds the coconut and circles it seven times anticlockwise around the person?s head, after which he, chanting all the while, sacrifices the cockerel.

During our diverse trips to the north and to the south of Chhattisgarh, we paid particular attention to the problems of conservation, which condition the future of the art. In our descriptions of the sites we took care of mentioning their state of conservation whenever necessary.

The art may be imperiled by two main causes: degradations by humans, and by natural elements.

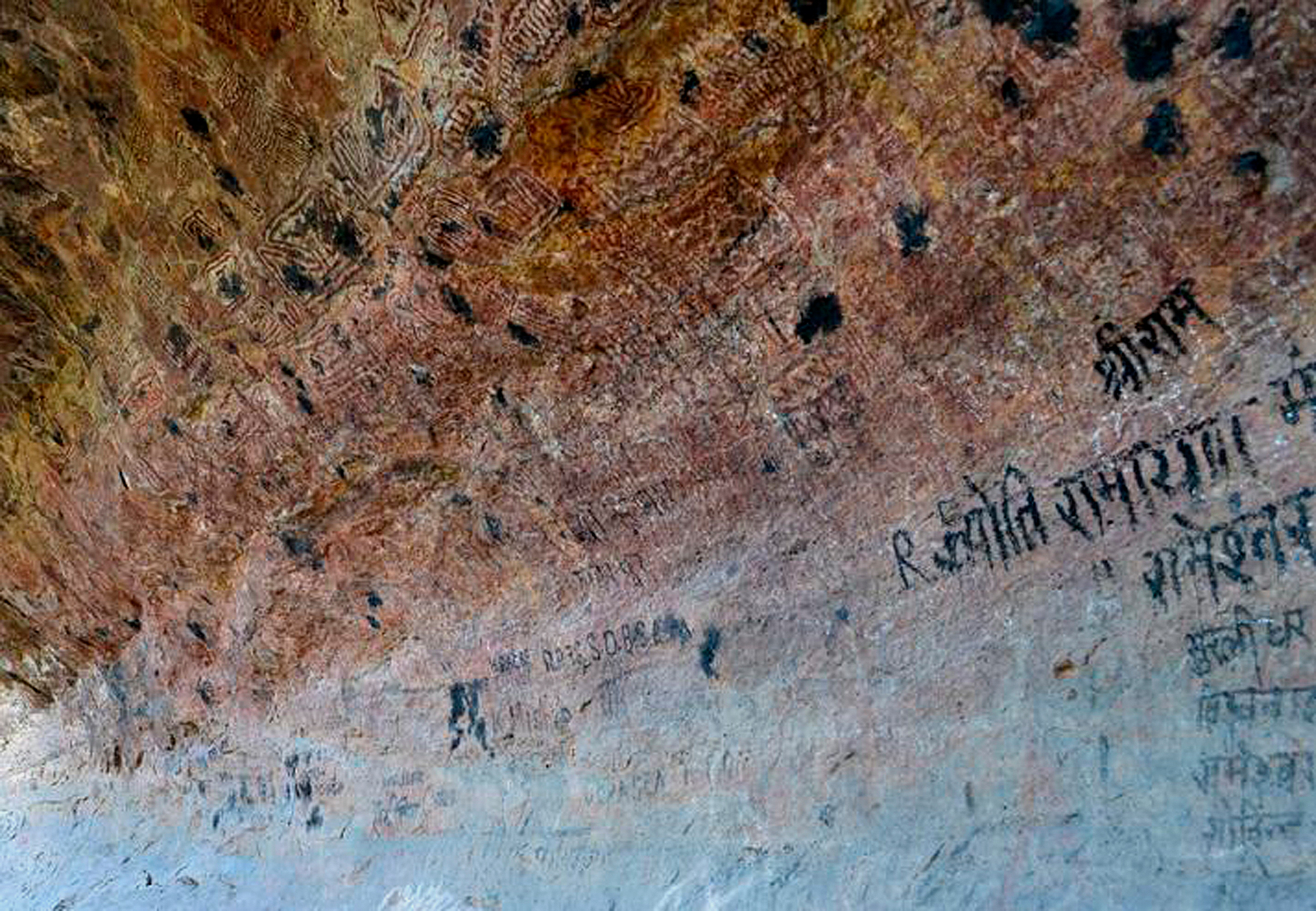

The degradations by humans are principally due to ordinary vandalism, such as writing names on the painted walls (Figure 11). We have also had examples of painted sites that were more or less destroyed by the modern religious Hindu inscriptions and practices of local villagers.

On the other hand, quite a number of rock art panels are faded or have been seriously damaged because of their exposure to natural elements (sun, rain, washing off by running water, etc.) as the paintings were never made inside deep caves but on the walls of exposed shelters.

Trying to avoid voluntary or involuntary vandalism is the clearest and most obvious option. Two possibilities come to mind:

- Building a fence around the rock art panels for them to remain out of touch and be protected. We talked about it with the authorities in charge who entirely agreed about that necessity and will carry out all necessary protections;

- Setting written panels warning not to damage the art. Those panels should be visible to visitors while being always put in a place of the shelter where there are no paintings and without touching the wall. We suggest setting up panels and chain-link fencing or railings in all the important sites.

One final important point is that, given the importance of many of the painted sites for the local tribal people who entertain strong religious feelings about them, their beliefs and religious practices should be respected by all. No further damage or changes should be done to the sites: in particular, nobody should build walls, make fires, cement the ground or add script or images. It would probably be fruitful to trust the local tribal people with the conservation of their sites as unofficial or official guards.

This article is based on 'Powerful Images, Rock Art and Tribal Art of Chhattisgarh' by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak and Jean Clottes , a book published in 2017. Bloomsbury Publications, New Delhi.