An article by Gerard Hindmarsh on stuff.co.nz - Maori rock art sites our cathedrals - reports on the Maori rock art of the South Island of New Zealand.

At Craigmore Station, inland Timaru, the Cave of the Eagle takes its name from a painting of the now extinct Haast Eagle (harpagornis moorei) which decorates the overhang's ceiling. Image: Gerard Hindmarsh.

The author is visiting a rock art site in a remote part of South Canterbury, having begun his journey at the Te Ana Rock Art Centre in central Timaru. It is a Ngai Tahu-owned visitor centre run in conjunction with guided tours of Maori rock art sites in the area. Exactly 580 rock art sites exist within the tribe's South Island boundaries and 250 of those are in the Timaru area, many on private land.

The author explains that the Centre attempts to recreate an experience of walking onto a marae, except the wahine singing the authentic karanga is a state of the art hologram projection on a glass screen. Mentioned are the four historic tribes thought to produce all the art. Generally, the authenticity is maintained through interactive displays and dioramas. There are also exhibits of rock art, all of which had been cut from their cave by early scholars keen to preserve them.

Then to the rock art in situ: the author visits Rock Farm near Cave, just inland from Pleasant Point, and shown what is locally called Dog Rock, a massive limestone outcrop in the middle of a huge hillside paddock.

A grill now protects the rock paintings in an overhang of Dog Rock, on Rock Farm near Cave. Image: Gerard Hindmarsh.

Two sheltered overhangs contain the paintings which are now protected by a grill. The two guides explain that no one knows exactly who made the rock art in the country's first art galleries.

The shelters examined by archaeologists were used by some of the South Island's earliest inhabitants. The Maori rock art reveals different styles. Repeated motifs through the rock art include animal figures, mythical creatures and abstract patterns. The arrival of Europeans was documented in the art.

At Craigmore Station further inland, the author visited the Cave of the Eagle (Te Ana Pouakai), where a painting of the now extinct Haast Eagle (harpagornis moorei) decorates the overhang's ceiling. The earliest paintings here are attributed to Waitaha people. Alongside, a human form is depicted front on, with the core of the torso uncoloured. Symon, the guide, speculates this may have been their mauri or soul, while bird people depictions she says represent the intermediaries between people and sky.

Maori rock art of the South Island of New Zealand. Te Ana Rock Art Centre https://t.co/TVWXuq3iQb pic.twitter.com/Xam2VziQcQ

— Bradshaw Foundation (@BradshawFND) October 30, 2018

A human form in the Cave of the Eagle (Te Ana Pouakai) is depicted front on, with the core of the torso uncoloured, the blank maybe representing the person's mauri or soul. Image: Gerard Hindmarsh.

All of the motifs have parallels with the most ancient Maori artefacts and carvings, even if many of the subjects appear simplified and more streamlined than the detailed and elaborate designs found in later classical Maori carving, weaving and ta moko .

The author explains that elements of South Island rock art are similar to the rock art found across the Pacific, from Hawaii to Easter Island. Polynesian navigators brought with them a palette of motifs, with the tiki - or human figure - being the most commonly depicted. Once here, these traditions transformed and evolved over time to become unique to this land.

Craigmore Station, the cave of the Eagle is situated lower left, at the base of the limestone outcrop. Image: Gerard Hindmarsh.

Most of the rock art was painted rather than drawn, using black or red pigments on naturally smooth, light-coloured limestone. It is thought artists may have used brushed made of plant fibre, sticks or just their fingers to apply the paint to the rock surface. Some art was carved or incised into the rock. Variations of white or yellow were created by abrading the limestone surface, which prepared the rough rock canvas for the intricate designs.

According to one traditional southern Maori recipe for black paint, the green branches of the resinous manoao tree were burned, the smoke directed to settle against a flax mat. Scraped off, the soot was mixed with gum from the tarata (lemonwood), oil extracted from the berries of the rautawhiri (black matipo) along with weka oil. The result was 'an ink that would stand forever'.

Over the centuries the corrosive forces of nature have taken their toll, and rising salts have affected the surface of the porous limestone. However, human interaction has caused the greatest damage, either by deliberate vandalism or by the best intentions of scholars.

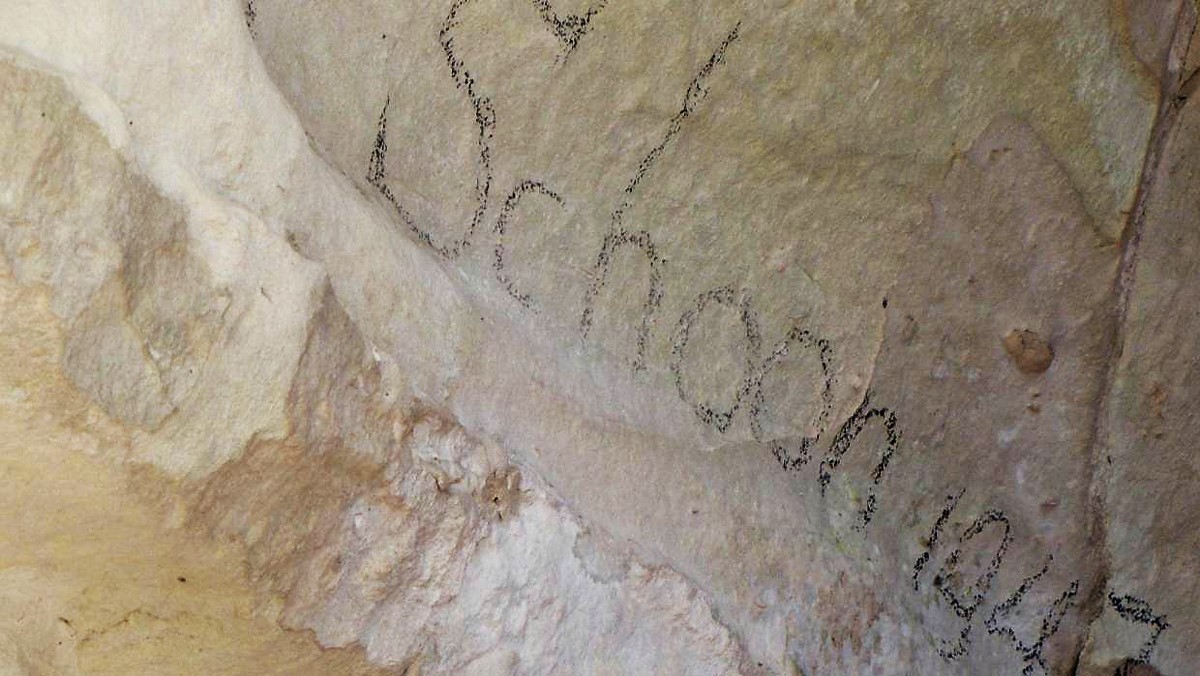

Dutch artist Theo Schoon left his signature in the Cave of Eagle in 1947. He was contracted by the government to document all our rock art, but couldn't resist touching them up at the same time. Image: Gerard Hindmarsh.

In the past, some researchers damaged the integrity of the art by tracing over the faint originals works with house paint, chalk, ink and grease crayons. Theo Schoon, a Dutch painter who was hired by the government in the late 1940s to document the rock art, routinely touched them up with chalk and 'Moa' brand oil crayons that were in common use in schools at the time.

Te Ana Maori Rock Art Centre:

https://www.teana.co.nz/

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 09 August 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 24 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 01 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 March 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 28 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 23 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 31 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 September 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 17 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 09 August 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 24 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 01 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 March 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 28 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 23 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 31 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 September 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 17 July 2023

Friend of the Foundation